Compare these two pieces. First, one of Henry Purcell’s fantasias for viols (1680). A short figure is imitated between voices, summoning a detailed web of melancholy counterpoint. The idea is spun out in elaborate developments: upside down, the entries piling up closer together, the tail extended into a sequence. The music contorts itself into harmonic paradoxes and clashes, perhaps reminiscent of the wit and double meanings of poetry by those other 17th-century Englishmen, John Donne and Andrew Marvell. This is music of great beauty and sophistication, but where does the piece as a whole take us? It falls clearly enough into large-scale sections (beginning at 1:38, 2:30 and 3:15) differentiated by a new character, tempo and theme. But their sequence feels additive rather than cumulative, with little sense of an overall narrative arc. To us modern listeners, the effect is something like looking at a richly embroidered tapestry, as if each line of counterpoint were a thread in a seamless, two-dimensional foreground.

Now try the first movement of Haydn’s 47th symphony (1774). Everything about it sounds in motion, from the level of each phrase to the piece as a whole – more like telling a story than seeing a static object from multiple angles. Each phrase is clearly directional, carefully proportioned, and distinct from its neighbours. Like a tour of the rooms and gardens of a rococo palace, the piece as a whole has a strongly differentiated beginning, middle and end: setting off, passing through varied surroundings, and returning to an altered version of where we began (from 4:16) with the benefit of experience. (Both halves of the movement are themselves repeated – if you want to hear it all through once, listen from 1:24 to 5:26). The music seems to evoke not just linear time but something like spatial depth; events in the musical foreground whose succession feels compelled by a purposeful underlying structure.

What changed in this century or so between Purcell and Haydn? Three crucial innovations of musical composition are part of the story. One is a much greater variety of texture – the surface events and gestures of the music. Another is a more unified, integrated approach to overall structure, based on large-scale repetition and resolution. The last is a new system of harmony that was able to create a sense of proximity and distance, foreground and depth, over extended periods of time. I want to suggest some parallels between this 18th-century musical lingua franca and a familiar device from another medium: modern realist prose, which emerged through the 17th and 18th centuries – just when these musical conventions took shape.

We habitually associate literary realism with things like down-to-earth subject matter, plausible detail and convincing chronology. For the ancients, though, realism had just the opposite meaning. Aristotle argued that art should transcend the mass of incidental details around us and deal with the more important reality of universals. On this view, art imitates reality not by directly copying things around us, but by somehow reflecting our broad experience of reality through its modes of representation. But in the wake of the empiricist philosophy and science of the 1600s and 1700s, this idea was turned on its head: what was ‘realistic’ was now the flux of particulars. This updated notion of realism found classic expression in the novel – novels that depicted particular people having particular experiences at particular times and places. For the literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, writing in the 1930s, the quintessential feature of the modern novel was ‘heteroglossia’: a riotous mixture of voices, characters and styles, which undermines the claim to authority of any one of them. And this opens up a tempting musical parallel.

In the early decades of the 18th century, just as the first modern novels were gaining purchase among a new reading public, a new kind of opera from Naples was sweeping Europe. It was a comic style later called opera buffa, distinguished from its forebears by its depiction of multiple character types. Opera seria (and its French equivalent, tragédie lyrique), to which buffa was a democratic alternative, had been based principally on classical subjects featuring characters of noble or mythological origin. It was structurally more static, too: each seria aria froze the forward motion of the plot and expressed the singing character’s particular passion at that moment, through highly conventionalised means. In the new comic style, contrasting styles, textures and topics jostled together in close proximity; this dazzling variety was imported from the opera house into instrumental music by mid-century galant composers like Giovanni Battista Sammartini and Johann Stamitz.

In his dialogue Rameau’s Nephew (1805), Denis Diderot has his title character both advocate and imitate the disjointed discourse of the modern style. ‘We need exclamations, interjections, suspensions, interruptions, affirmations, and negations,’ he says. ‘No more witticisms, epigrams, neat thoughts – they are too unlike nature.’ Whereas a string of arias in a Handel opera seria (or a sequence of dance movements in a baroque suite) each inhabit a singular affect and isolated vantage point, an ensemble finale in a comic opera or a symphony movement of the later 18th century give us a carnival of distinct characters.

There are few consistent spatial or temporal relationships, and little sense of realistic cause and effect

So one thing in common between novels and certain musical genres of the period is a palimpsest of voices and styles, a seething mass of surface particulars. But they are just that – a surface. I want to turn to a more profound theory of realism to recognise isomorphisms between the arts on a more significant level.

In her book Realism and Consensus in the English Novel (1983), Elizabeth Deeds Ermarth argues that a central preoccupation of realist art in general, both in literature and painting, is the projection of a neutral, communal sense of time and space. Premodern narratives, in her account, were typically structured around separate, unreconciled points of view. (Battle scenes in the Iliad, for instance, describe one hero attacking and then another falling, rather than the fight between them.) Each character has a destiny tied to the centre of the universe. Things gain their significance in relation to the divine order, not to each other. There are few consistent spatial or temporal relationships, and little sense of realistic cause and effect.

The later achievement, according to Ermarth, was to create a point of view that was anonymous, arbitrary and partial, but at the same time a unifying force: an ‘energy source everywhere in the work’ that serves to ‘homogenise the medium’. A central device of the realism of the 18th and 19th centuries was the invisible narrator. This all-knowing voice creates the illusion of a shared, quantifiable reality, allowing writers to unify huge volumes of detail through naturalistic vectors of space and time. And the sense of unity is not just spatial and temporal, but psychological. When we freely move between the interior thoughts of two characters in a novel by George Eliot or Dickens, we gain insight into their minds through the unifying consciousness of the narrator.

How might music of the same period reflect these preoccupations? To make the connection, we have to look at two fundamental features of the Enlightenment’s musical language: form and harmony.

Writing to his father from Paris in 1778, Mozart described the success of his latest symphony:

[J]ust in the middle of the allegro a passage occurred which I felt sure must please, and there was a burst of applause; but as I knew at the time I wrote it what effect it was sure to produce, I brought it in once more at the close.

What’s new here is not just the notion of a composer tailoring his music to the tastes of a public concert audience (though new it was). A more subtle emphasis in his words is upon the very idea of music’s sequential disposition.

In his book Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow (2007), Karol Berger argues that an important shift in musical temporality took place between his two titular composers: a static, ‘eternal Now’, evoking the timelessness of the divine, giving way to a dynamic and goal-directed flow of time. In the middle of listening to one of Bach’s fugues, it’s actually quite hard to locate ourselves in the overall structure. Bach is concerned with the potential for development of his fugue subject (heard alone at the beginning) – a catalogue of inventions that could take place in almost any order. On the other hand, once music’s specific sequential ordering was felt to be significant, a piece could be understood as in some way analogous to a story. Later 18th-century listeners therefore came to hear music in explicitly narrative terms.

For an early biographer of Haydn, one of the composer’s symphonies brought to mind a story of considerable complexity about man setting sail for America. His account freely mixes musical detail with narrative, each influencing the other:

At this point, the opening theme of the Symphony returns. But soon the sea begins to grow rough, the sky darkens and a fearful tempest advances with a clashing of key-signatures and a quickening of the tempo. Aboard the ship all is wild disorder. The cries of the sailors, the pounding of the waves, the howling of the gale whip up the melody from chromatic to pathetic.

One thing in particular allows the musical structures of Mozart and Haydn to afford a sense of narrative, and it’s something so obvious that it usually goes unmentioned. Repetition of one kind or another is endemic to most music as a basic tool of coherence – like the close-knit imitation between voices in that Purcell we began with. But larger-scale formal repetition, which involves a significant passage of music repeating on a broad, structural level (perhaps in some kind of ‘resolving’ way the second time, after a contrasting middle) is a higher-order, emergent feature: it depends on a surface varied enough to enable larger structures to stand out in relief. In itself, this was nothing new; just think of the refrains of popular songs since time immemorial. But over the long 18th century, it becomes a virtual sine qua non across all genres, and not just when motivated by a verbal text.

Most of this music seems to lack endings of any real force, given the low degree of internal tension to resolve

Vivaldi’s concerto movements, for instance, alternate between an orchestral ritornello (‘return’) in various related keys, and more exploratory episodes for the soloist. Almost every movement of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, composed between 1800 and 1824, involves a decisive structural return: from the revolutionary quest of the Eroica symphony’s first movement to the humble clockwork-driven intermezzo of the eighth. A reprise might be as modest as in many of Domenico Scarlatti’s three-minute sonatas: two halves, each repeated, the second shuffling around some earlier ideas and sealed with a pithy ‘end rhyme’ with the first half. And even the most capricious and whimsical sorts of pieces rely on it. C P E Bach’s fantasias for keyboard, impulsive expressions of inner sensibility, and Schubert’s impromptus, notated records of the composer’s far-reaching improvisation at the piano, all repeat long passages.

It might seem as though the very idea of literal reprise is so basic as to be inevitable, but it’s actually a striking rarity in music before the later 17th century. A cantata by Carissimi or Schütz, or an instrumental piece by Marini or Sweelinck (all of the early to mid-1600s) fall into clear sectional structures, but without a sense of overall repetition. The keyboard virtuoso Frescobaldi even prefaced his first book of toccatas (1615) with permission for the performer to start and end each piece wherever desired, conceiving of the music more as a compendium of effects and affects than an integrated plot to be followed from start to finish.

Unity might be achieved through other means: a repeating but developmental formula like a ground bass, or a pre-existing popular tune or chorale melody unfolding slowly in one voice. Notice, too, how most of this music seems to lack endings of any real force, given the low degree of internal tension to resolve. (By contrast, fast-forward a century and a half to Beethoven’s famously long and tautologous endings: they sound like absolutely necessary outcomes of what precedes them. Like a large aircraft needing a long runway to slow down, the ferocious forward momentum of the music needs a proportionately satisfying grounding.) Heard through ears trained by 18th-century conventions, this earlier music can sound somewhat open-ended or structurally ‘flat’ – perhaps akin to the experience of reading certain pre-realist literature. In his great study Mimesis (1946), Erich Auerbach writes that medieval prose romances ‘string independent pictures together like beads’, each separated by blank intervals of time and no sense of historical progression. In medieval and other pre-perspectival painting, too, each object or figure exists in its own foreground, with no overall vantage point to create a single spatial continuum.

A musical reprise has an inherent doubleness, a simultaneous past and present. It functions as an index of time elapsed and distance travelled. An important feature of realist narrators is a similar temporal doubleness: a present-tense narration of past events arranged in a clear sequence, giving the story a forward-straining direction. (This may have a philosophical provenance: in early modern thought, especially Locke and Hume, the relationship between memory and present awareness becomes an increasingly important determiner of personal identity.)

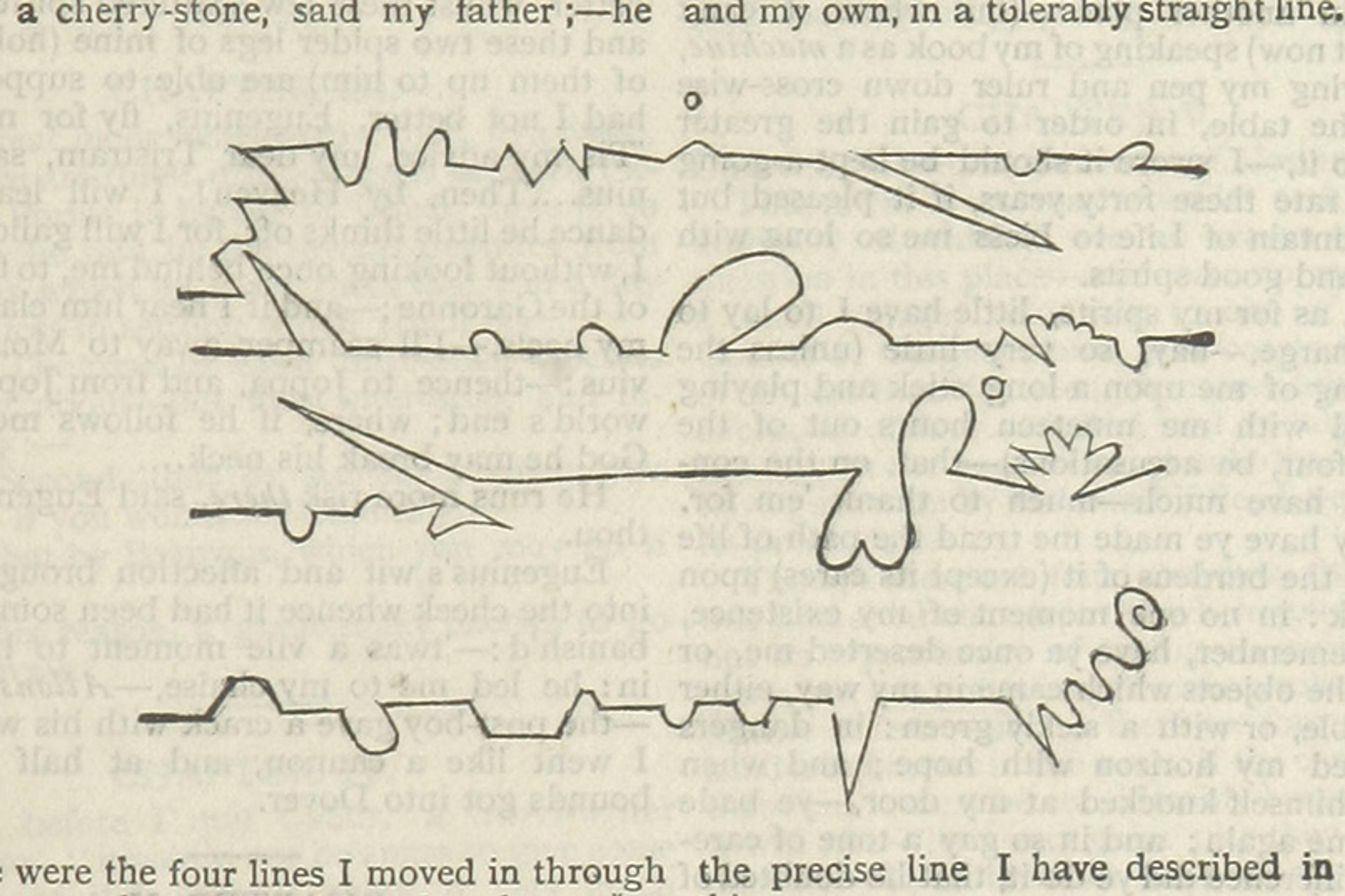

A vivid example of this convention in its earliest, most vulnerable phase is Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740). Much of the story is told through a series of letters from the maidservant heroine, some written just moments after the events they describe. The story constantly threatens to catch up with the telling. Writing to her parents to complain of untoward comments by her master, she quickly signs off, later explaining: ‘I broke off abruptly my last letter; for I feared he was coming; and so it happened.’ Laurence Sterne’s novels take as their subject the possibility of linear storytelling itself: an autobiography that can’t decide on its own starting point and barely gets beyond age two and a half (Tristram Shandy, 1759-67) and a travelogue of a journey through France and Italy with no clear purpose and the destination never reached (A Sentimental Journey, 1768). The desire to include incidental details undermines the plot, because the sheer weight of detail stalls the narrative’s forward motion. But Sterne equally satirises its opposite, the idea of pure forward motion without pausing to take in anything on the way. Vowing to the reader to proceed at last with fewer digressions, Shandy draws literal ‘story lines’ that purport to illustrate the motion of his plot. The absurdity is clear: what would be the point of a story told in a straight line? How would it even be possible? Music and literature seem to discover the possibility of integrated, linear storytelling at almost the same time. To us, these techniques are second nature; back then, there were anxieties over it, as one can have only over something in its precarious infancy.

Plot lines in Tristram Shandy (1759-67) by Laurence Sterne. Courtesy the British Library

We can find parallels that run just as deep in music’s harmonic dimension. Ermarth relates the narrative techniques of modern prose to the linear perspective first achieved in Renaissance painting: both represent time and space in communal, quasi-objective ways (the ‘consensus’ of her title). In perspectival art, all objects in a picture are situated in relation to a vanishing point. The picture plane itself intercepts imaginary lines that radiate from each object and converge on the viewer’s eyes, a simulation of the three-dimensional space that we perceive in the world. I want to suggest that the powerful engine of 18th-century tonality evokes something like this sense of spatial depth.

Earlier music relied in various ways on a creaking and inconsistent modal system. A mode (in this sense) is a scale made up of particular patterns of intervals. Each mode has a distinctive harmonic colour, and each tends to be associated with other musical traits, like recurring melodic formulas and characteristic emotions. As far back as the Republic, Plato banishes the ‘indolent’ Lydian from his ideal state but retains the ‘warlike’ Dorian. (The ancient Greek modes, it should be said, were quite different to later systems.) There was frequent ambiguity about the status of the modes: theorists in the 1500s and 1600s disputed their importance or even existence, seeing counterpoint as fundamental, and the modes merely as a system of classification. By the early 18th century, there were effectively only two possible modes left: our modern major and minor. This was a dramatic simplification that unlocked a great expansion. The energies of tonality – something like a gravitational or magnetic force between notes, chords or keys – could now operate on a much grander scale.

Realist narrative relies on an accretion of insignificant details like this

Listen to this dance music by Jean-Baptiste Lully for Molière’s comedy Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670). The music is full of familiar gestures and cadences – the gravitational forces of tonality – but without moving away from the home key for long enough to escape its influence. We could say that the music temporarily rests ‘on’ other closely related keys, rather than moving ‘into’ them. Now try this concerto grosso by Corelli from just two decades later. The music now feels like it moves decisively ‘into’ nearby keys. Those local cadences in the Lully are stretched out over longer spans of time in the Corelli, spans that are padded out and given a phenomenological depth by the whirling, repetitive figurations for the soloists. Rather than dwelling on the bejewelled surface of a distinctive mode for its duration, music now began to move systematically between different transpositions of its starting key: what we call modulation. The power of tonal harmony is its recursion. It moves in the same way in its surface gestures as on a higher level.

Eighteenth-century pieces dramatise this potential for longer-range harmonic motion. A movement of a Vivaldi concerto or Haydn sonata stages a harmonic journey away from a tonic key to a closely related one, through more distant regions, before a satisfying homecoming. Each of these modulations requires an imaginary sort of ‘effort’, typically by the suggestion of a delicately weighted sequence of fifths above each new key. We have seen how large-scale repetition can suggest something like temporal depth. Could the tension we hear in a tonal piece between these two related ‘angles’ – the key we are in at a given moment and the overall tonic – produce something like a spatial equivalent?

Another way of looking at this is to say that harmonic structure becomes fundamentally relational, not absolute. Critics have detected just the same quality in the realist prose that flowered in the next century. Commenting on Flaubert’s description of a living room, Roland Barthes suggests that the piano might indicate the bourgeois standing of its owner and the boxes and crates a sign of messiness or decline of the household – but the barometer is just there, ‘neither incongruous nor significant’. Realist narrative relies on an accretion of insignificant details like this. These details are not symbolic or allegorical, alive with meaningful resonances; their only purpose is to evoke the texture of reality.

Characters in premodern literature are bundles of allegorical attributes, all their qualities open to view at all times. In John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678-84) their very names announce who they really are: Christian, Hypocrisy, Goodwill. In later novels, on the other hand, when we meet a new character, they could be just about anyone. We discover who they are by accompanying them on a journey of experience through time and space. And so in music: a modern key doesn’t have any of the unique characteristics or flavours of one of the older modes – though some of these characteristics did survive through convention. All of them – any major or minor scale – have the same internal structure. What matters is how you get from one to another.

In philosophy from René Descartes onwards, matter is thought to be inert extension, devoid of meaning and spirit. Nature is homogeneous, to be measured with the uniform tools of geometry and clock time. This is the intellectual background to linear perspective and the techniques of literary realism. They go hand in hand with the new mechanical philosophy; they all express the modern impulse to rationalise. Erwin Panofsky, in a discussion of Italian Renaissance painting, suggests that linear perspective ‘seems to reduce the divine to a mere subject matter for human consciousness’. The musical techniques explored above play their own part in this story. A movement of an 18th-century mass also rephrases religious truths in ways comprehensible to the earthly. The liturgy is now arrayed along tonality’s rationalising, perspectival grid. Perhaps we, the listeners, replace God as the ideal vantage point of the music.

Revolutions in art don’t take place overnight, and many aspects of 18th-century music were caught between older and newer conceptions. Already present in J S Bach’s music, for instance, are the powerful forces of goal-directed tonality that he derived from the Italian concerto style, even though (as Berger argues) Bach is best thought of as a late representative of the older model of musical time. And much of the idiosyncratic music of the 1600s shows features in outline that would become more important in the next century. One of the first operas, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo of 1607, contains (appropriately enough for a story about a return from the Underworld) a ritornello punctuating its recitative-driven scenes. Each repetition summons us over and over again to Euridice’s fatal look back.

If we look at later 19th-century music, these conventions are as enduring – and as unquestioned – as their counterparts in literature and painting. The young Richard Strauss’s Don Juan (1889) is a virtuosic rendering in music of the seducer’s tale. The Don Juan legend itself has no literal large-scale repetitions. So why does Strauss feel the need to write a long, balancing reprise of the opening music (starting at 14:23) when there can be no direct literary justification? Perhaps he felt it necessary in order to achieve a ‘purely musical’ coherence, as a novel or painting achieves for itself by different means. Tellingly, the composer’s own written programme for the piece, which matches moments in the music to the story, falls silent during the long repetition – as if the passage were as integral but almost as unremarkable as the proscenium arch of a theatre or the canvas of a painting.

The textbooks call the late 18th century’s music the ‘Classical’ era. In some respects, it’s an unfortunate label, giving a serene, abstract (and just plain ‘old’) quality to music that we could hear as endlessly contemporary and loaded with worldly significance. But perhaps there is a sense in which this music can be thought of as a ‘classical’, or perhaps a ‘classic’, style. The devices of literary realism, too, became classic: powerful but invisible conventions that pass themselves off as nature.