On a wintry day in Bordeaux, France, I took refuge from the rain inside a cosy bookshop stacked to the ceiling with books. Place Gambetta, Bordeaux’s iconic square framed with majestic 18th-century limestone façades, was under construction. ‘It’s always like this,’ the owner told me with a disparaging glare. I was not sure if the comment was directed at the rain or the construction. Inside, I browsed the shelves, soaking in the titles one by one. A book cast among thousands caught my eye: La vie à en mourir: lettres de fusillés (2003). It contained farewell letters of those shot by Nazi firing squads during the German occupation of France in the Second World War.

I picked it up, opening the pages slowly and carefully as if I held in my hands a fragile treasure, like ‘this butterfly wing’ which the 19-year-old Robert Busillet, executed for his role in an intelligence-gathering and sabotage network, bequeathed to his mother ‘en souvenir de moi’, to remember him by. I flitted through the pages, reading flashes of a letter here, longer passages there. As someone who studies war, I am no stranger to the theme of killing and dying. But this experience was different.

Last letters are unlike any other type of writing I have ever encountered. They are of a singular ilk because they peer into the souls of those confronting imminent and inescapable death. Different from everyday letters, diaries, memoirs, political tracts or philosophical treatises, because of the urgency that shapes the act of writing. The authors know there will not be another chance to say what must be said.

Each last letter is uniquely personal, yet there is a universal feel to them, almost as if they paint a naked portrait of the human condition. To read them incarnates the phrase penned by Michel de Montaigne. ‘If I were a maker of books,’ he wrote in the 16th century, ‘I would make a register, with comments, of various deaths. He who would teach men to die would teach them to live.’

Dawn breaks on your final morn. A prison guard hands you a blank sheet of paper and a pen two hours before your execution by Nazi firing squad. The customs and traditions of the time – sometimes, but not always, respected by the Nazi authorities – permit the condemned a final act of communication: the last letter. To whom do you write? What do you say, knowing this is the last chance to say it?

It’s not just the heroic resistors whom the Nazis executed. One could be killed for far less. In the autumn of 1941, the Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich – the military commander who controlled Paris – enacted the ‘hostage code’, whereby all those in a state of incarceration are considered to be political hostages. In the event of a ‘terrorist attack’ – an act of armed resistance against the occupier – these political hostages could be executed in reprisal. In other words, those arrested and imprisoned for, let’s say, writing or distributing illegal tracts and newspapers, protesting in the streets, or even listening to news from forbidden radio sources such as the BBC were, effectively, handed death sentences-in-waiting.

I’ve read hundreds of last letters, written by armed resistors and political hostages alike. One day, I sat down to catalogue the ways in which the soon-to-be executed communicated to their loved ones the macabre news. It was an uncomfortable, but deeply moving, task.

‘Be courageous, ma chérie. It is no doubt the last time that I write you. Today, I will have lived’

‘I can give no longer any further testimony of my affection than this letter,’ began Robert Beck, the head of an active terrorist organisation, according to the Gestapo. ‘Colvert will never again see his Plouf, nor his little Plumette. He is leaving for a big big journey,’ he added, softening the blow for his children.

Jacques Baudry, who had resisted the Nazis since his high-school days when he organised protests and marches, later participating in armed attacks against the occupiers, was rather blunter in his letter to his mother: ‘They are going to rip me from this life that you gave me and that I clung to so.’

Huynh Khuong An, a young high-school teacher arrested for possessing anti-fascist propaganda and related clandestine activities, was plucked from the cistern of political hostages one sunny October day. Writing to his lover, he implores: ‘Be courageous, ma chérie. It is no doubt the last time that I write you. Today, I will have lived.’ This turn of phrase, so simple grammatically speaking, is deceptively philosophical because it captures the interval that separates the writer from the reader, the one who will have lived from the one who lives on. Death was no longer on the horizon. The moment was decided, imminent and irrevocable.

To read the letters is to take a journey inward, deep into the world of emotions at the very frontier of living and dying. In one’s final moments, superficiality cuts away, revealing something meaningful and deep about the human condition. From Montaigne:

In everything else there may be sham: the fine reasonings of philosophy may be a mere pose in us; or else our trials, by not testing us to the quick, give us a chance to keep our face always composed. But in the last scene, between death and ourselves, there is no more pretending; we must talk plain French, we must show what there is that is good and clean at the bottom of the pot.

The last letters communicate what this something, at the bottom of the pot, is.

One of the most powerful theories to explain how humans face up to their own mortality was hypothesised by the American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her groundbreaking book On Death and Dying (1969). When an individual learns of their impending death, they navigate among five stages of grieving, trying to come to terms with their own mortality: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Kübler-Ross observed terminally ill patients with a limited time horizon. For those killed by the Nazis, that interval was often condensed to the time allotted to write a letter.

The last letters offer a raw portrait of grieving one’s own demise. Few of the condemned deny their fate. Some remain entrenched at the phase of depression. Others skip a phase, or oscillate between anger and acceptance, acceptance and depression. A surprising number traversed all the phases. And almost everyone bargains. Bargaining means asking the question: what would I do, if only I had more time? Montaigne would have us focus on the passages related to bargaining because these, by showing us what is at the bottom of the proverbial pot, teach us to live.

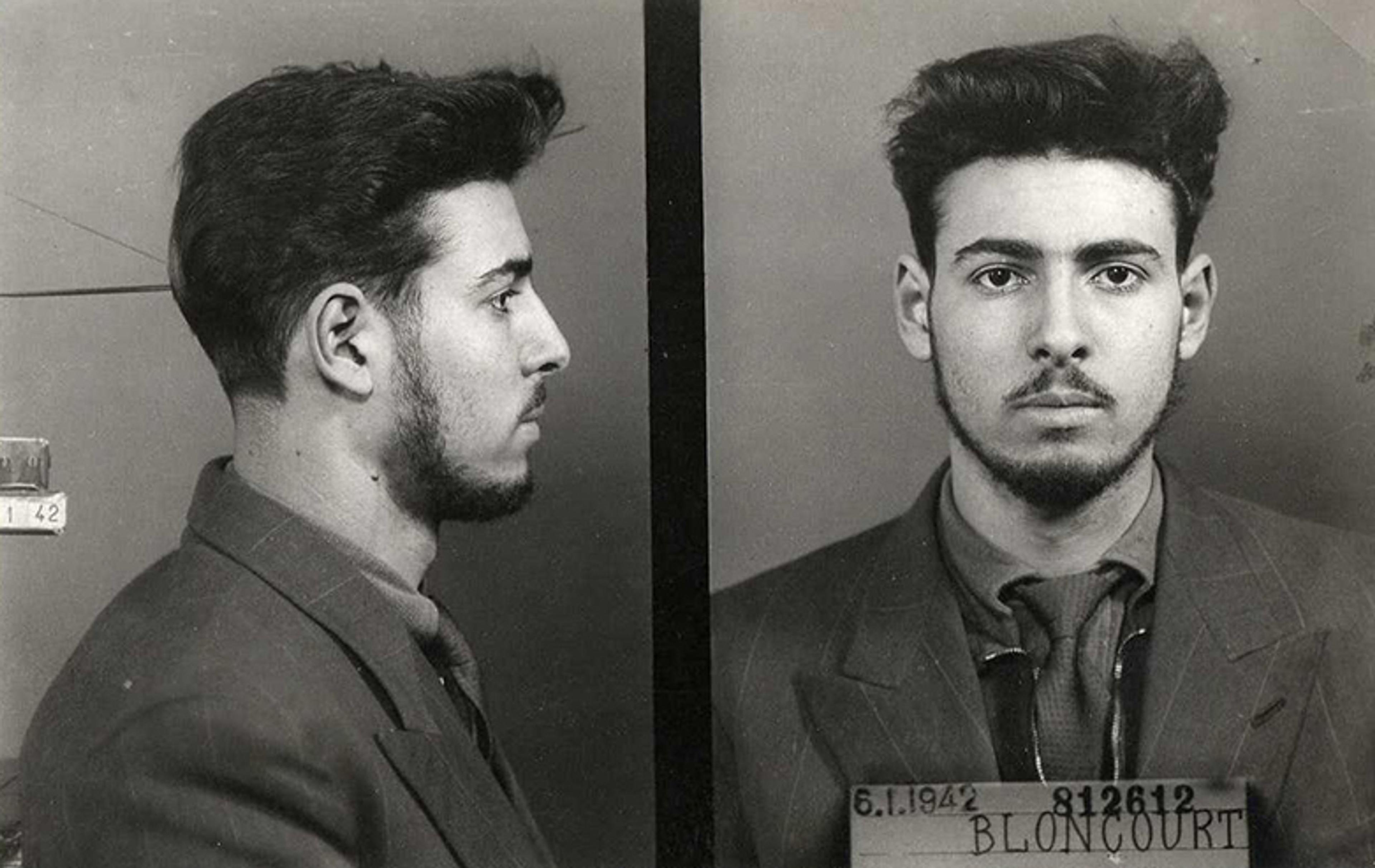

If the last letters are any proof, the adage that your life passes before your eyes has some truth to it. It’s not the classic image of an entire lifetime; it’s more like watching old movie reels of favourite moments. ‘I do not feel the need to sleep,’ explains Arthur Loucheux – a well-known anti-militarist and leader of a miners’ strike – to his brother at 2 am of his final night, ‘not out of fear, but to remember my life, because to sleep, bah! won’t I have time [to do so] very soon?’ Tony Bloncourt, or ‘petit Toto’, who was part of a youth battalion and partook in armed resistance, recounts to his parents: ‘My entire past comes to me in a flash of images.’ A life of 21 years. Was he thinking, as he wrote, of the years he would not live to see?

Tony Bloncourt. Photo from the police files and courtesy Ministry of Defence, Paris

As I read their words, I’m hit by a flash from my own past. It’s a story I often tell my students who are planning to study abroad because it depicts a quintessential encounter between me, a culture and its language. It’s a story about the little details that convey so much about local history, hiding in plain sight. There is a last-letter link, too, though at the time I did not know it.

As the execution looms ever closer, he bargains with time, perhaps in shock that tomorrow will not be just like yesterday

I was on my way to a lunch, navigating still-unfamiliar streets to my destination, at the crossroads of rue de Vouillé and rue Georges-Pitard in the quaint 15th arrondissement of Paris. The names meant nothing to me back then. I was oblivious to the stories that marked the public spaces I transited and inhabited.

I had just arrived in France and was still learning the language. To help me practise my grammar skills, someone had the bright idea to impose a very peculiar rule: every spoken sentence had to employ the subjunctive in some way or another. Any basic French grammar book will tell you the subjunctive is used to indicate some sort of subjectivity, or uncertainty, in the mind of the speaker. Feelings of doubt and desire, as well as expressions of necessity, possibility and judgment. The subjunctive inhabits many last letters. Georges Pitard’s letter to his wife, Lienne, begins with the subjunctive, used as an expression of necessity: ‘It is necessary for you to be extremely courageous, because this time misfortune is upon us; it flashed like lightning and it strikes us.’

Pitard, I would eventually learn, was a lawyer who defended those unjustly imprisoned at the beginning of the occupation and was arrested for it. A man of principle: ‘I only did good, thought of easing misery,’ he wrote in his last letter to his wife before being executed as a political hostage. ‘But for some time now the elements are raging and everything conspires against men like me.’ Knowing these details adds a layer of meaning to my memory and its resonance, with the last scene playing out again and again each time I tell the story. Pitard’s final words always the same.

We can imagine a 40-something Pitard in his cell writing these words as time inexorably ticks and tocks. He seems to regret that ‘we quarrelled a few times, hurt each other for trifles’. As the execution looms ever closer, he bargains with time. Remembering the past, perhaps in shock that tomorrow will not be just like yesterday, he writes: ‘This evening, I think of your sweetness, your kindness, of our sweet moments, those from long ago and those of yesterday, know well, my darling, one could not love you more than I did.’ He seeks one final escape from the fate that awaits him, in a place where everything is pure love, where nothing else exists except dreams of her: ‘And I will fall asleep with your sweet image in my eyes and the taste of our last kisses that are not that distant, my sweet friend, my gentle little Lienne. Be sensible … Be reasonable. Love me, for a long time yet.’

The subjunctive again. Expressions of desire and longing. When time seems like an infinite plain before us, we take the days ahead for granted. There will always be time to do the things that matter most. Too often, maybe, these are a small part of a bigger canvas often dominated by other priorities.

Time duly runs its course, and the letter comes to an end, but not before ‘Geo’ adds a postscript: ‘I kiss passionately your photograph and press it to my heart, the first [photo] of our youth, and the one from Luchon in which you are wearing flowers.’

I imagine him in the dark of night, pressing his lips to the photo. Reliving the memories. When Lienne reads his letter, Georges will have lived.

Despite the raw emotion of the last letters, it’s hard to imagine that the elements, raging, will conspire against me. Psychologically, as humans, we flee from the idea of the world carrying on without us. We push the fact of dying deep into our subconscious. Instead, we take comfort in the naive belief that tomorrow will be like yesterday, and so on, and so forth. Such is the power of denial.

I remember the exact moment when the façade of denial began to crumble. To plunge deeper into the ambiance of the dark years of the Nazi occupation, I searched out other writings from the time. I found a copy of La patrie se fait tous les jours, an anthology of texts from the French intellectual resistance. It was a first edition. The pages were crisp, still uncut, as if the book had just come off the printing press. Except it had been published in 1947, less than three years after France was liberated.

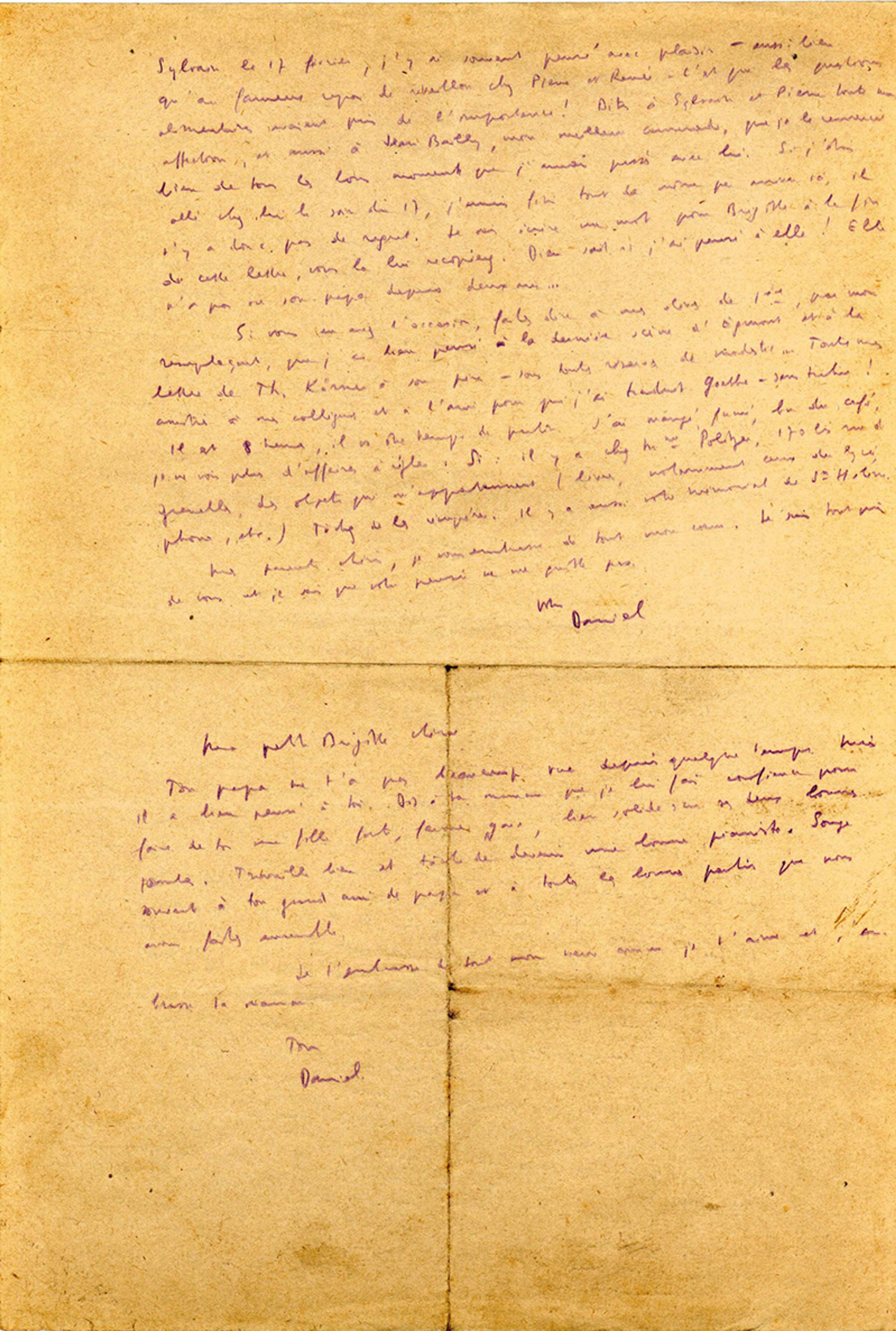

To leaf through the pages required, first, slicing them apart. The same movement one makes to open a letter, it turns out. It was a slow and meticulous process. I dutifully opened them, lingering to read a poem by the resistance poet Paul Éluard – ‘Liberté’ (1942) – until I arrived at page 111. There, as I carefully opened the next few pages to reveal the last letter of Daniel Decourdemanche (known by the pseudonym of Jacques Decour) – a French professor of German literature in his 30s, living in Paris – something happened. Psychologically, it was like the floor fell out from under me, plummeting me into the tumult of the times.

To whom would I write? What would I say? Am I ready to die? What would I bargain for?

Decourdemanche was part of the intellectual resistance. His crime, which led to his May date with a Nazi firing squad, was to organise and distribute underground magazines, whose purpose was to rally intellectuals to the anti-fascist cause, and to inject some humanism into news cycles gorged with nationalist and divisive propaganda.

In his last letter, tempted to imagine what might have been had he had more time, Decourdemanche writes to his parents: ‘I dreamt a great deal, this last while, about the wonderful meals we would have when I was freed.’ But he accepts these experiences will not include him: ‘You will have them without me, with family, but not in sadness.’ Instead of regret, his mind drifts to the meaningful experiences he did live: ‘I relived … all my travels, all my experiences, all my meals.’ And at the end: ‘It is 8 am, it will be time to leave. I ate, smoked, drank some coffee. I do not see any more business to settle.’

I sat there, moved but immobile, staring at these last lines, then at his signature. ‘Votre Daniel’, your Daniel. I had the strange impression of looking in a mirror, of staring death in the face. Another Daniel, also a humanist in a world of inhumanity and ruthless self-serving politics.

The last letter of Daniel Decourdemanche. Courtesy the Mont Valérien Memorial

Reading his words, I drift across the thin frontier separating the past from a parallel world. In reading how he and others confronted death, in bearing witness to their fears, hopes, joys and regrets, I am instinctively transported to an analogous moment. To whom would I write? What would I say? Am I ready to die? What would I bargain for? That’s what the last letters do, they open this frontier and beckon us to cross.

Montaigne counsels his readers to come to terms with death by learning to no longer fear it. This has a liberating effect, according to the old sage, because it allows us to be more in tune with ourself while we are among the living. The trick is to cultivate what is at the bottom of the pot long before the final act.

Reading the last letters allows us to play such a trick on time. For we, the readers, are still in the world of the living. We are not yet part of those who, when the ink dries on the page and it is read by loved ones later, will have lived. Maybe we do not know what, when the time comes, we might bargain for. But the last letters tell us what those on the other side of life wanted, what they bargained for, at death’s door.

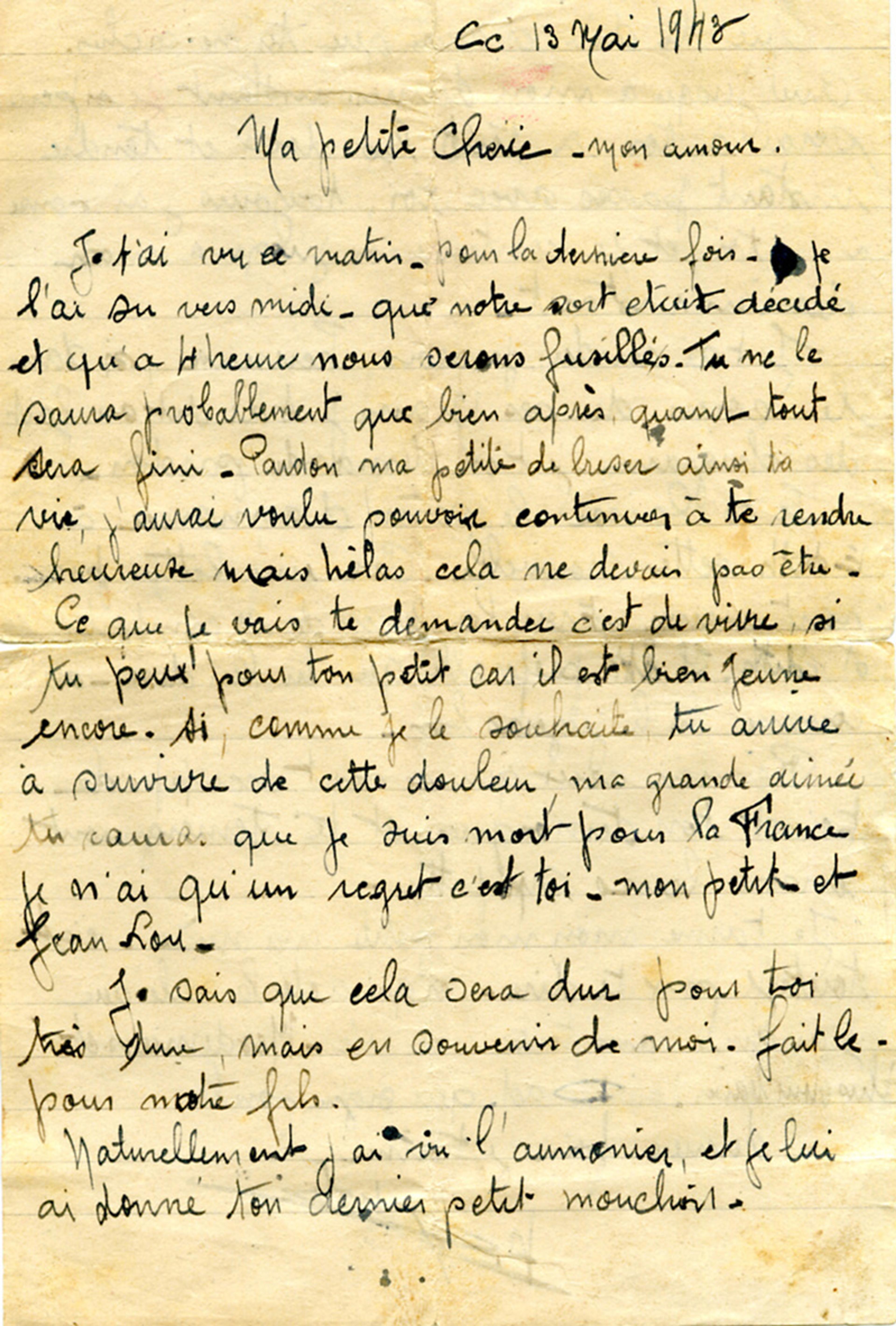

The verdict had fallen. Forty-one-year-old André Cholet, condemned to death for running the radio counter-espionage wing of a major resistance group, had just seen his wife for the last time. He recounts the scene in his last letter:

I still have the time to talk to you ma petite, as if you were still here close to me, on the other side of the wire mesh. For this last day you were beautiful like you had never been before and oh what grief is now yours. I would like to be in this moment still.

The last letter of André Cholet. Courtesy the Mont-Valérien Memorial

Bargaining to be there in that instant. To see her eyes, her smile. To smile back. To soak up all the non-verbal gestures that define a person, a loved one, her. To blow a kiss. How seldom do we remark these moments in normal times? They seem unremarkable when lived day to day, but in the last scene, between death and oneself, the emotions, hopes and regrets that comprise the human condition are heightened a thousandfold. What if we were attuned in such a way that daily encounters with loved ones were heightened a thousandfold? Or even just tenfold?

The final lines of Lalet’s last letter suggest that, deep down, he realises that anger, however valid, is empty sustenance

Bargaining is the bedfellow of regret. Twenty-one-year-old Roger Pironneau was not sorry for the espionage that led to his arrest. He does not regret resisting. But, writing to his parents, he is sorry ‘for the suffering I caused you, the suffering I am causing you, and that which I will cause you. Sorry to everyone for the evil that I did …’ And he is sorry ‘for all the good that I did not do’. I imagine his mind wandering – let’s be clear, even though there is no chance, no illusion, of actually having more time, it wanders toward a question we readers can still pose: if only I had had more time, what good could I have done?

Last letters are finite. They contain the words that fit the page allotted, and no more. What is not written remains unsaid. Arrested for acts of sabotage and other clandestine activities, Maurice Lasserre composes his last letter to his wife, Margot. He signs his name one last time, with the unique characteristic furls that make his signature his. There is just enough space for a final PS: ‘I close the envelope by cherishing you and kissing you for the last time, again good kisses. I send you my wedding ring and a lock of hair that you will keep in memory of me …’ As he folds the letter to place it in an envelope, something unexpected happens. ‘They are giving me more paper,’ he notes below his signature, before continuing on a fresh page. ‘I take advantage to write to you again and to kiss you still once more …’ One more gesture of love. ‘And the little ones, and the older ones, too.’ Lasserre writes on. A message for each of his children. And one more thought destined for Margot: ‘Still more kisses and think that I am yours, even in face of the death that is coming.’ Another sheet of paper is like a new day, though if we thought it might be the last, perhaps our perception of the most ordinary of gestures would change.

Bargaining exposes the raw core of what gives meaning to the everyday gestures. When we are young, we think there will be an infinite number of blank pages upon which to write our story. Twenty-something Claude Lalet found himself, the morning of his last day in the world of the living, writing to his new bride. Sure, he was active in various protests, which led to his arrest. But it was never supposed to end like this, being executed as a political hostage in reprisal for the assassination of a German officer by the armed resistance. In the back of a truck on the way to the quarry where he is to be executed, he composes himself: ‘Already the last letter, and already I have to leave you!’ The repetition of the word ‘already’ betrays his anger; it’s simply not fair, his fate.

But Lalet does not want to dwell in anger. Focusing on the beauty around him, he observes in poignant prose: ‘Oh the road is beautiful, ah, truly!’ As the truck rumbles forward and reality sinks in deeper, he battles to keep his bitterness at bay. What was it that made life so wonderful? ‘I know I must clench my teeth. Life was so beautiful; but let us hold on to, yes hold on to our laughs and our songs …’ Lalet has every reason to be bitter, but the final lines of his last letter suggest that, deep down, he realises that anger, however valid, is empty sustenance: ‘Courage, joy; immense joy … I love you always, constantly. I kiss you, I hug you with all my strength. Long live life! Long live joy and love.’

All those whose letters are cited above died at the hands of the authoritarian state. They came from all walks of life and diverse political backgrounds. Some took up arms to fight back, while others resisted non-violently, or were simply caught up in the repressive nets of the state. I reread their last letters in parallel to the newsfeeds that, every day, bring ubiquitous headlines stirring nationalistic and xenophobic sentiments. Even if I cannot quite wrap my head around the absurdity of being in a position of writing my last letter, there is foreboding in the air.

Instinctively, I look for parallels in the past, drifting back across that frontier the last letters have opened to me. Daniel Decourdemanche wrote in his diary in 1938 on the eve of the infamous Munich Agreement:

One prepares oneself, one ponders about what is to come, about what must kill us without our being able to have a gesture of defence, but it will maybe take a long time, like all incurable maladies. Waiting so long for the inevitable, this is the test.

Would it make a difference if everyone confronted their own mortality in earnest?

The diary entry is a prescient bookend to his last letter penned in 1942, before he was executed in the glade at the sinister Mont-Valérien fortress on the outskirts of Paris. As he watched the forces of history unfold, Decourdemanche was no doubt thinking of the possibility of his own death – a life cut short by the tumult of the times. ‘How to find your way around?’ he asks, in a world in which humanism is a bad word, where vitriol is the coin of the realm. Where the dykes of civility and tolerance that once kept fanaticism at bay have burst. Where there is power in hating the other, in calling the other names, in blaming the other for all our problems. As if doing so acts as a shield against whatever may come. ‘The strong who face this test,’ he proffers, ‘are not those we expect.’ Falling in step, toeing the line of intolerance, embracing the newly emboldened toxic masculinity? No. ‘The strong,’ Decourdemanche surmises, ‘are those who loved love more than everything else.’

‘It is the right time for us to remember love,’ he tells himself. ‘Have we loved enough,’ he asks? ‘Have we spent several hours a day marvelling at others, being happy together, feeling the price of contact, the weight and value of hands, eyes, the body? Do we still know how to devote ourselves to tenderness?’

These are formidable questions. Once you realise that your days are numbered, that other emotions are competing for time and space in your life, answering them offers a chance to reorient yourself amid all the noise and contempt: ‘It is time, before disappearing in the trembling of an Earth without hope, to be entirely and definitely love, tenderness, friendship, because there is nothing else. One must swear to only care about loving, to love, to open your soul and hands, to look with the best of your eyes, to hold what you love close to you, to march without anguish, radiating tenderness.’

Back in the 21st century, this Daniel wonders how many people around him are having the same existential thoughts. Would it make a difference if everyone confronted their own mortality in earnest? Thinking of the bottom of the proverbial Montaignian pot amid the constant brouhaha, the rhetoric, the posturing and pretence of a world clutching at madness, I ask myself the question that those who can still bargain for time should ask: how might I live my life differently?