An estimated 30 per cent of babies born in medieval Europe died before their first birthday, and a further 20 per cent did not survive to adulthood. For individual families, the impact could be even greater: seven of King Edward I’s 16 children died before their seventh birthday, while Catherine of Siena’s mother gave birth to at least 23 children, but only eight lived to adulthood. Such high mortality rates are largely explained by the extreme susceptibility of the very young to malnutrition, childhood ailments such as measles and diarrhoea, and epidemic diseases. Medieval chroniclers often claimed that the majority of the plague-dead were children, and the archaeological record provides further proof of their vulnerability: the excavation of one Sienese cemetery suggests that, during the 1383 outbreak, 88 per cent of plague victims were children.

Confronted with such distressing evidence, some historians – notably Philippe Ariès, in his pioneering study Centuries of Childhood (1962) – have argued that medieval babies were largely ignored, society being unwilling to invest time, resources and above all emotions in fragile beings who had an extremely high chance of dying young. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest that premodern people loved and cared for their children, and grieved them when they died. Although few recorded their feelings as eloquently as Petrarch, many medieval parents would surely have identified with his account of his infant grandson’s death:

I was profoundly shaken to see the sweet promise of his life reft away at its beginning … My love for that child so filled my breast that I cannot think that I ever loved anything else on earth so much.

It should not, then, surprise us to learn that medieval people were extremely interested in babycare – especially as contemporary medical theory held that the child was extremely delicate, and needed special treatment. According to medieval understandings of the body, health was based on the equilibrium of the four humours (blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile), and illness was the result of humoral imbalance. Very young children were naturally hot and moist, and these qualities needed to be maintained but not enhanced. This meant that the child’s environment must be carefully managed, since an individual’s health was believed to be greatly influenced by a set of external factors known as the non-naturals (air and environment, diet, sleep, movement, excretion, and emotions), all of which had the potential to change an individual’s humoral make-up, and to cause illness. For this reason, it was very important that a baby was protected from cold draughts, kept calm, and got plenty of sleep. Above all, it must be given a suitable diet, which meant that medieval texts about babies are (like their subjects) preoccupied by food – and specifically with breastfeeding.

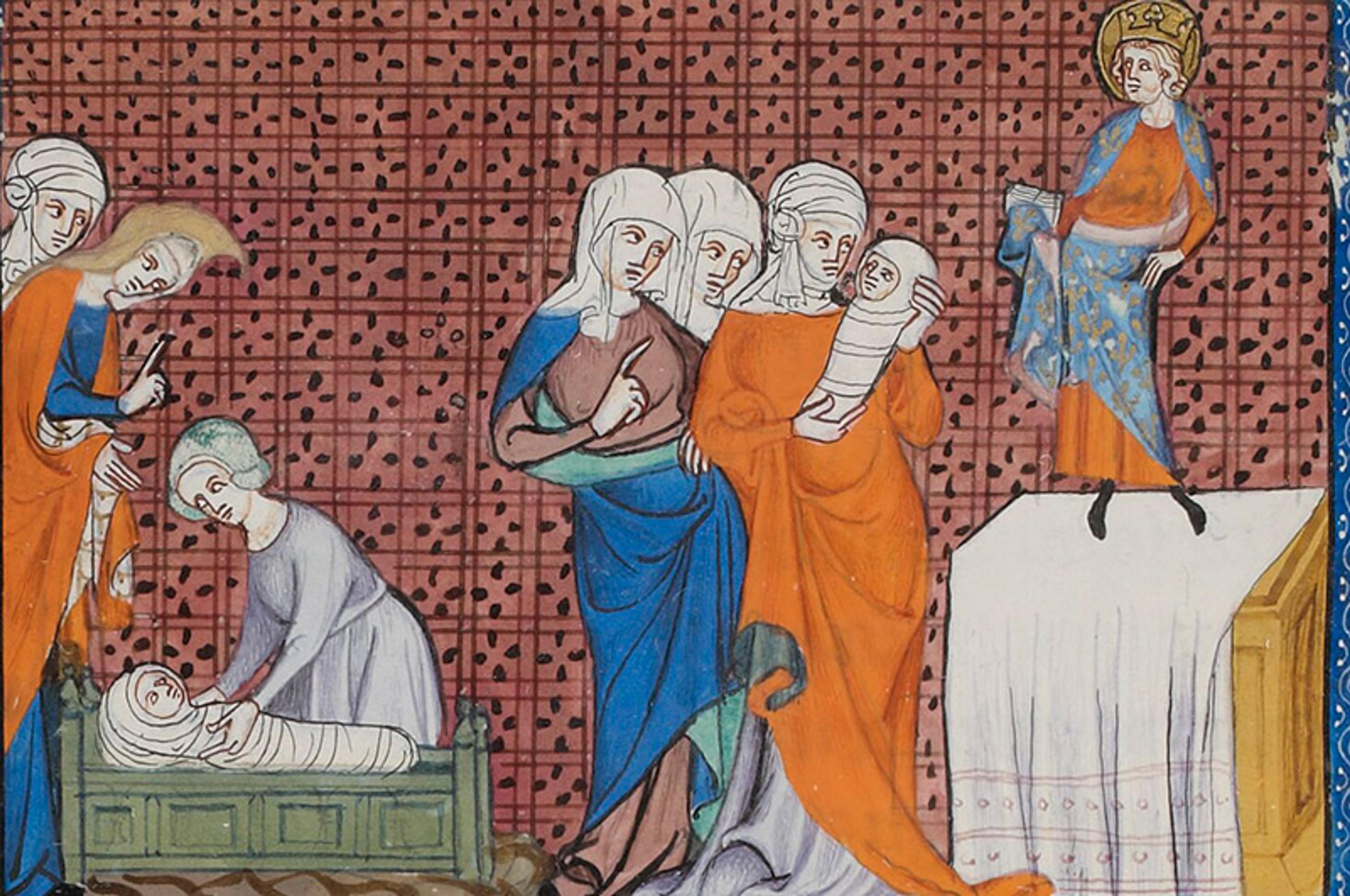

La jeune accouchée. From Comédies (c1410) by Térence; manuscript 664, fol. 230v. Courtesy the BnF, Arsenal

Indeed, if modern mothers often feel pressured by the ‘breast is best’ brigade, at least they don’t have to live up to the impossibly high standard set by the ideal medieval mother: the Virgin Mary, who was often depicted nursing the infant Christ. Saintly women such as the 12th-century Ida, countess of Boulogne, who insisted on nursing all three of her sons herself, were lauded for emulating Mary’s maternal devotion. Such was Ida’s commitment to this practice that, when she returned from mass to find that another woman had fed her screaming son for her, she made the baby vomit. Nevertheless, the damage was done, and this brother was always less successful than his siblings.

Ida’s concern, and the meaning of this story, was rooted in the many medical arguments in favour of maternal breastfeeding. According to the 13th-century physician Aldobrandino of Siena, the mother’s milk was always the best option, ‘because this is what he was nourished on when he was in his mother’s womb, and after he is out of the womb the milk reverts naturally to the breasts.’ (The exception was the milk produced immediately after giving birth – whereas modern medicine places great emphasis on the benefits of colostrum, medieval physicians feared that the upset of labour damaged this milk.) The milk given to a baby was the main influence on its health: medieval people took quite literally the idea that an infant ate what its mother did, and her poor diet could leave the baby’s humours out of balance. Consequently, bad milk could lead to all sorts of unpleasant illnesses, from acute problems such as ‘spewinge’ and ‘squirte’ to serious conditions such as leprosy and epilepsy.

Breastfeeding also shaped the child’s character, and not just because it spent a lot of time with its mother, developing a close emotional bond with her. (According to the 15th-century Venetian humanist Francesco Barbaro, one of the key differences between women and female animals is that the former have nipples on their chests rather than their stomachs, which allows them to fondle their child as they nurse.) A woman’s characteristics, good and bad, were thought to be passed on through her milk, so that a wise, pious mother like Ida would produce wise, pious sons – and the child of a drunkard or a fool would follow in its mother’s misguided footsteps.

Then as now, nursing mothers received lots of advice about their technique, diet and lifestyle. Most medical writers agreed that women fed their babies too much and too often; they suggested a schedule of well-spaced feedings (possibly as few as two or three a day), but claimed that many women effectively fed on demand. Among the foods to be avoided were onions, duck, freshwater fish, fruit and strong wine, all of which would overheat the body, corrupt the blood and thus spoil the milk. Nursing women were advised not to have sex, which would reduce both the quality and quantity of the milk, and above all must avoid conceiving, for ‘a pregnant woman when she nurses destroys and kills children.’

Women who did not breastfeed their own children were criticised in the strongest terms by both churchmen and medical writers. The 13th-century English theologian Thomas of Chobham insisted that a woman’s refusal to nurse her baby was tantamount to murder, while refusing to use her breasts as God intended was a form of blasphemy. The 15th-century Italian physician Michele Savonarola was equally hostile, asking: ‘How can you not want to breastfeed your child, taking into consideration the quality of his care, his good health and wellbeing, and even your own health and longevity?’ Many male proponents of breastfeeding accused non-nursing mothers of prioritising their looks and their lovers over the wellbeing of their offspring. The 15th-century Valencian physician Jaume Roig blamed his son’s death on his wife’s vanity about her figure, which meant that the child was sent to incompetent wet nurses.

An animal horn could be used in place of a baby bottle. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

Nevertheless, many mothers were either unable or unwilling to nurse their own children. For us, the obvious alternative is bottle feeding but, in an age of limited sanitary facilities and no formula milk, this was not an ideal solution. Although nursing horns were sometimes used, they were rarely seen as a good choice. Writing in the 14th century, the grain merchant Paolo da Certaldo warned that ‘a baby who nurses on animal’s milk does not develop like a child who is nourished with human milk; rather, he always seems somewhat stupid and empty-headed and not with full understanding.’

Consequently, many babies were fed by wet nurses. For high-status women, a wet nurse could be a status symbol, but she also allowed the dynastically minded mother to focus on having more children. (Medieval people were well aware of the contraceptive effects of lactation.) And if wealthy women often delegated the task because they could, the poor sometimes did so because they had no choice. In 1442, a Florentine father called Niccolò Ammanatini explained his poverty to tax officials: ‘[My] wife has no milk and we must hire a wet nurse.’ In 14th-century Montaillou in France, poor girls were sometimes obliged to hand over their babies so that they could work, though some were reluctant to do so. When Brune Pourcel was encouraged to leave her six-month-old son Raymond with ‘a woman from Razès who has too much milk’, she initially resisted, fearing that ‘Her milk would be bad for my son.’

One potential nurse had plentiful milk, but was flighty; another was described as ‘evil’, and had only one eye

So, what did parents look for when employing a wet nurse? The ideal candidate was around 30, in robust health and of sound moral character, and with a strong resemblance to the nursling’s mother. Her breasts should be firm and medium sized (very large breasts might squash the child’s face, making it snub-nosed), and her milk should be white, sweet, and neither too thick nor too watery. Ideally, she should have given birth about two months previously, although she must not nurse her own child alongside her new charge.

In practice, finding such a paragon was hard to do. In 15th-century Prato, Margherita Datini was often tasked with finding nurses for the offspring of her merchant husband’s wealthy Florentine friends. The job was frequently a difficult one. One potential nurse had plentiful milk, but was flighty; another was described as ‘evil’ by her last employer, and had only one eye. Datini was suspicious of any wet nurse who had a toddler, writing: ‘Never shall I believe that when they have a one-year-old of their own, they do not give some [milk] to it.’ All too often, her success rested on another woman’s tragedy, as when she told her husband: ‘I have found one in Piazza della Pieve, whose milk is two months old; and she has vowed that if her babe, which is on the point of death, dies tonight, she will come as soon as it is buried.’

Some nurses moved in with the family: in August 1328, for example, Beatrix Rossel hired herself to Berengarius Sesmates, a skinner of Perpignan, ‘to live with him and nourish with her own milk his children Petrus and Johanna for one year starting immediately.’ In Florence, however, parents often sent their children away to nurse, as the city air was thought to be unhealthy for delicate young bodies, and so it was particularly important that the woman was carefully chosen. A wise parent visited often, and would move their child if its care was inadequate. Thus little Francesco Guidini was sent to Monna Andrea in November 1380, and stayed with her for a year. When she became pregnant, he was transferred to a new wet nurse. When, a year later, Monna Mina announced that she was now expecting, his parents decided that he was old enough to be fully weaned, and kept him at home.

As little Francesco’s experiences suggest, medieval babies were often breastfed for much longer than their modern counterparts: skeletal evidence from England and Scotland indicates that breastfeeding typically stopped around the child’s second birthday, and some women continued for even longer. In the 15th century, María Garcés testified that she had found a 15-day-old baby on the steps of Zaragoza Cathedral. Her own son having died, she fed him ‘with milk from my breast’ for three years – possibly inspired by the popular belief that Mary fed Christ for three years.

For much of this time, breastmilk would have been given with other food and drink, with the introduction of solids often coinciding with the eruption of the first tooth. Suitable weaning foods included bread (either pre-chewed by the mother/nurse, or soaked in sweetened water), thoroughly cooked rice, and puréed chicken. Rather disconcertingly, very young babies sometimes seem to have drunk wine – and in sufficient quantities that the 15th-century German physician Bartholomäus Scherrenmüller discussed what a nurse should do ‘if she cannot get the child off wine’. (The answer was to give it white wine, well diluted.) Not everyone thought this was a good idea, with some authorities stating that the under-fours should never be given wine, which caused them pain and fevers. It is hard to tell how often medieval children were given alcohol, but the case of Agatha, who lived in 13th-century Salisbury, suggests that it was not unthinkable. When her milk dried up, she apparently gave her baby son beer for a whole week, after which she went to pray at the tomb of St Osmund, and her milk was miraculously restored.

He criticised the Irish, who ‘do not use hot water to raise the nose, or press down the face or lengthen the legs’

Once a baby has been fed, it usually wants to sleep, and for a medieval baby this often meant being placed in a cradle. Co-sleeping was frowned upon, because of the perceived risk of overlaying: sermons warned against it, and women were asked about it in the confessional. Many medieval miracle stories concerned women such as Ceccha, who shared her bed with her daughter Clarucia and her son Vannucio. One night she fell asleep while feeding and cuddling her children. When she awoke, Clarucia was senseless. Fearing she had smothered her daughter, she begged a local saint, Nicholas of Tolentino, to ‘free her Clarucia from death and to free herself from infamy’, and he reputedly performed a miracle cure for the unfortunate family.

Cradles not only prevented such accidents, but also improved the child’s health, because gentle rocking aided digestion and encouraged sleep. It was sometimes described as a form of exercise, which made sense in the context of contemporary medical theory, which saw exercise chiefly as a way of moving humours around the body. But rocking too hard was dangerous: the 14th-century Catalan mystic Ramon Llull warned that this was ‘contrary to the brain, which is shaken by rocking and does not achieve the aptitude it would otherwise attain.’

And the brain was not the only body part that needed to be handled with care. Medieval writers often stressed the softness of the infant body, comparing it to wax. Consequently, the baby’s body could be easily shaped into attractive forms (the 12th-century polymath Gerald of Wales criticised the Irish, who ‘do not use hot water to raise the nose, or press down the face or lengthen the legs’), but it could also be bent out of shape by something as apparently innocuous as a blanket or even its own movements. This was one of the reasons (along with cleanliness) why physicians suggested that babies should be bathed in warm water almost immediately after birth, and then at frequent intervals (around two to three times a day for the first month, and approximately once a week after that). It also explains the medieval enthusiasm for swaddling, which was widely used to keep children still during the early months when the body had not yet solidified.

From the illustrated Vie et miracles de saint Louis (c1340) by Guillaume de Saint-Pathus. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

Of course, the cradle was not always a place of safety. Based on the evidence of English coroners’ records, cradle-bound infants were extremely vulnerable to house fires, especially when unsupervised. William Senenok and his wife left their baby, Lucy, in the care of her big sister Agnes when they went to church on Christmas Day 1345. The three-year-old went out to play, and the baby burnt to death. Yet we should be wary of assuming that such neglectful parents were the norm, or that medieval babies were routinely ignored. Both legal and spiritual authorities condemned those who did not take good care of their children, and public opinion was also against them. In early 15th-century Pomerania, Elizabeth found her seven-month-old daughter Margaret dead in her cradle on returning from a night out. She and her husband were distraught, because this was the second child they had lost; their toddler son had died after falling into some boiling water. Now the couple feared that people would say: ‘Look! Coming from a party, again they neglected their child.’ Fortunately for all concerned, the child was miraculously revived thanks to the intervention of St Dorothy von Montau.

Even parents who stayed at home with their child might be criticised if they did not pay it enough attention, since the debate over whether babies should be left to cry is a very old one. Several medical experts suggested that they should be allowed to cry for a short time before feeding; this was good for them because it released noxious superfluities which might impede digestion. But others worried that wailing was a waste of breath, and it was generally agreed that it was important for a baby to maintain an emotional equilibrium, with caregivers being advised not to scare their charges.

One technique for encouraging speech development involved rubbing the gums with butter and honey

Moreover, there is plenty of evidence that medieval parents did their best to nurture their children and spend time with them. When medieval women described past events, they often mentioned the infant they were holding at the time, as when Guillemette Clergue told the Inquisition how she ‘was standing in the square at Montaillou with my little daughter in my arms’. Savonarola told women to play with their babies, and his suggestions are timeless ones: dangle an interesting object, so that he follows it with his eyes; move his arms around and tickle him; or lift him to his feet and gently bounce him. Ideally, the child’s environment should be a stimulating one, with interesting pictures and colourful cloths, and although few medieval baby toys have survived, we know that rattles were sometimes tied to cradles.

Babywalker. Les âges de l’homme, from Le Livre des propriétés des choses by Barthélemy l’Anglais. 15th century, France. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

Like us, medieval parents were preoccupied with teaching their little ones to talk, although some of their methods now seem rather unorthodox. One popular technique for encouraging speech development involved rubbing the mouth, and especially the gums, with butter and honey. This was believed to encourage the growth of teeth, the emergence of which would facilitate speech. In addition, one should sing to the child and talk to it, repeating easy words such as ‘mama’ and ‘papa’ that do not make the tongue move too much. In his 13th-century encyclopaedia, Bartholomew the Englishman describes how nurses whisper and lisp to children in order to help them talk, although not everyone approved of this practice: Sir Thomas Elyot, an early Tudor educationalist, described babytalk as a habit of ‘foolish women’. Fathers also had a part to play, by speaking correctly when in the company of their children. The content as well as the accuracy of their conversation mattered, and the 15th-century Florentine humanist Matteo Palmieri railed against parents who laughed when a small child said an obscene or blasphemous word, and who taught babies to make rude gestures at their mothers.

Learning to walk was another key skill, and Savonarola’s description of this process will be familiar to anyone who has ever spent time with a toddler. First, she should be encouraged to cruise along the furniture, and then persuaded to walk to you: call her name, or offer her a tempting object. He stresses that someone should always be ready to catch her as she falls, warns against leading her by the arms (which may hurt her shoulders), and even suggests using a small cart to help her in her efforts. Medieval manuscripts include numerous drawings of babywalkers, not dissimilar to those still used to teach babies how to walk. The existence of such objects, used to equip the child with the skills it would need in adult life, not only underscores the similarities between medieval and modern experiences of growing up, but also serves as poignant evidence that, even in an age of horrendously high infant mortality, medieval parents took good care of their children, just as we do today.