In early June 2018, I landed at Kansai airport in Japan, with a full day of travel ahead. A few hours later, I was sitting on a Shinkansen – the high-speed train connecting Osaka to Tokyo. Jetlagged, I tried to concentrate on the countryside as it streamed by at over 300 km per hour. Water was everywhere: a steady flow of wetlands, historical paddy fields, embankments. It was a watery procession, occasionally interrupted by a tangle of power lines and packed houses, the scars of centuries of hydraulic struggle.

What I saw was the symptom of a universal story. All societies are locked in a dialectic relationship with water over time. It falls from the sky, comes from the sea, flows over land: floods, droughts, storms are expressions of Earth’s climate. People respond, finding solutions to protect themselves. It is a story of action and reaction, of water encroaching on daily life, of catastrophic failures, of people organising to shift water’s course or hold its force at bay. What propels this story forward over centuries is the fact that the solutions of any age are transformed – or rendered obsolete – by the changing expectations of those who follow, in a never-ending human dance with water.

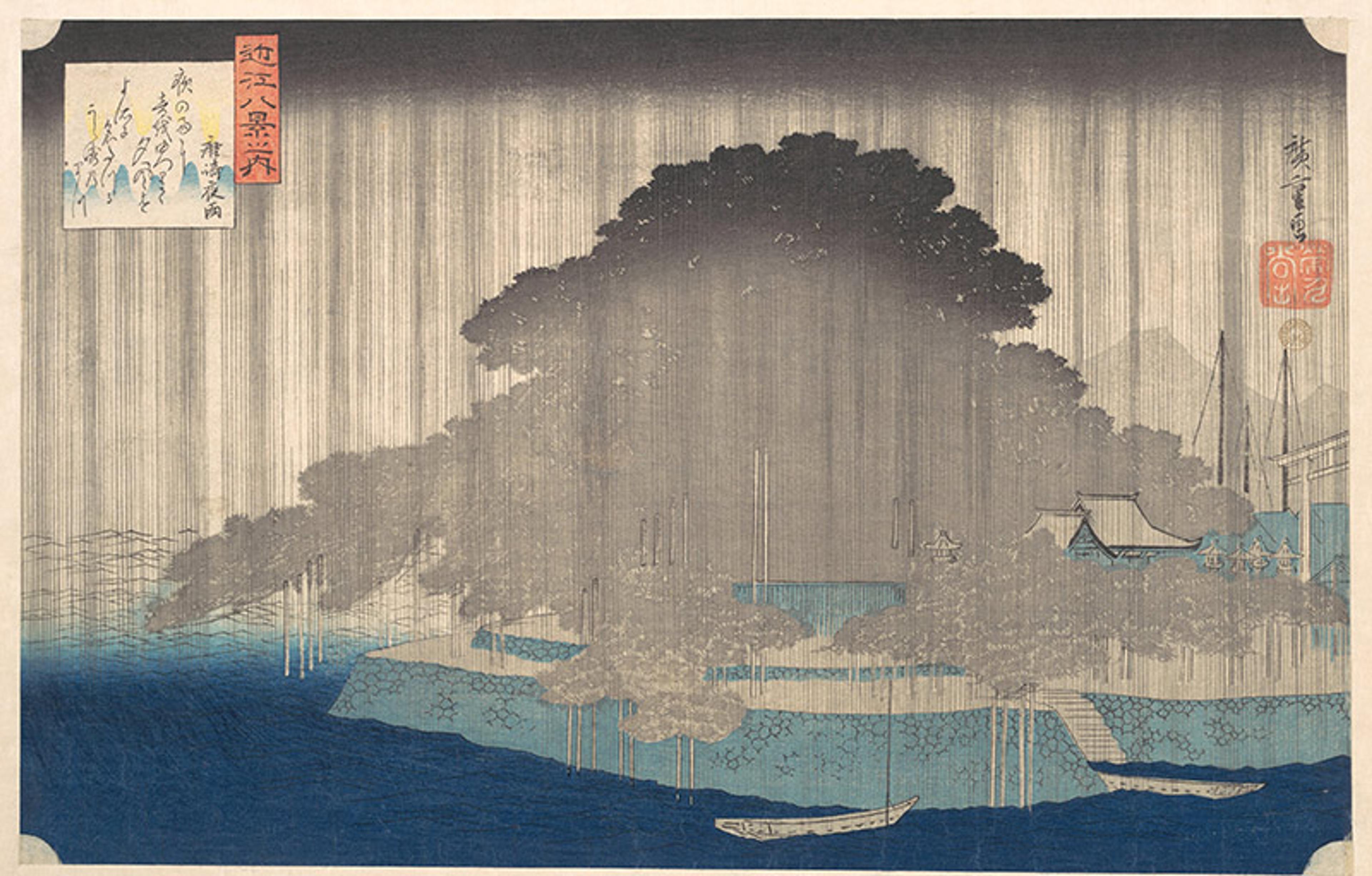

Night Rain at Karasaki by Utagawa Hiroshige. Courtesy The Met Museum, New York

The traces of that dance are etched into the landscape and institutions of society: the memory of what past generations did shapes what current generations can do. The question, in an age of unprecedented climate change, is whether this past has anything to contribute to the struggle we face. As the floods and droughts that define the extremes of everyone’s water experience become more frequent and intense than ever before, what role does our historical relationship with water play? As the music changes, do the steps we learnt over centuries help us in this new dance with water?

Answering this question is harder than one might think: the traces of past water solutions are often hard to detect. During the 20th century, most rich countries deployed exquisite skill and vast resources to sever their relationship with their water past, creating the illusion that water on the landscape is nothing more than a modern, inert stage on which life plays out at the rhythm of the industrial economy. They wished to engineer away water, along with its unpredictability, burying it under a modern control of nature. For the most part, they succeeded.

No one in London (or anywhere else in the developed world beyond the UK, for that matter) wades a river going to work. The ancient tributaries of the Thames – the Walbrook, the Fleet, the Tyburn and the Westbourne – are lost inside the city’s sewers. In the US, Manhattan has forgotten flowing water altogether, as ‘Manahatta’ – the island once watered by countless streams and springs – lies under a thick layer of 20th-century architecture. Most citizens of Tokyo or Osaka experience water from taps, a familiar jutting feature of bathrooms or kitchen walls everywhere in the rich world.

But as the train sped through Japan’s constructed landscape, I realised that its relationship with water had a singular characteristic. Water, though controlled, had not disappeared. Japan’s millennial landscape proudly bore centuries of visible scars from fighting with it. The past was in full view. Its legacy – the paddy fields, river development, levees constructed over centuries – seemed to be still central to the security infrastructure of the present.

Japan is not entirely alone in having integrated its water past visibly into the present. The Dutch, for example, rely on centuries of water management and associated historical infrastructure in their modern relationship to water. It is inevitable: the Netherlands is at the mouth of continental rivers and much of it is well below sea level, facing the same existential problems it faced in the 10th century. But it is an exception, alongside a few places like Venice, the ancient water city.

The country is supplied by infinite moisture

In most countries, water management is a modern solution to a contemporary problem. For the most part, the historical plumbing of Europe’s landscape is buried under the cultivated fields of a land that enjoys a benign climate. Places with far more complex hydrology – India, the Amazon, even the Western US – once had rich Indigenous traditions of water management, but colonisation all but erased them. Modern infrastructure is a discontinuity entirely unrelated to their hydraulic past. China and Russia were transformed by communism’s 20th-century ideological enthusiasm for hydraulic engineering. Almost everywhere, water’s past is archeologically interesting, culturally important, but appears to be functionally obsolete, making it hard to read in the present.

But not in Japan. Conditions there are an unusual mix of difficult hydrology and historical continuity. The climate of this large, rich country is among the most diverse in the world, stretching from fully tropical latitudes at roughly 20 degrees north (south of Okinawa) to 45 degrees north, at the tip of Hokkaido, where midlatitude storms dominate. Its topography adds complexity. During the rainy seasons, water collects in about 3,000 unforgiving, short rivers, draining all sides of the young, steep mountains that cover most of Japan’s territory, leaving marshes and swamps on what little flat land is left.

The country is supplied by infinite moisture, surrounded to the west by the warm waters of the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea, and the Pacific to the east. It is as if someone cut out the middle of the continental US, squeezed east and west coasts together, and drenched that thin strip with more water than the US or Europe receive at similar latitudes.

These conditions produce singularly complicated water problems. Tokyo’s metropolitan area, for example, is home to more than 37 million people, among the largest in the world, crammed in one of Japan’s few lowlands. It receives as much water as famously wet tropical locations such as Darwin in Australia. Because Japan is on the edge of the ‘Ring of Fire’ (the seismically active Pacific Ocean rim), Tokyo’s infrastructure is at greater risk of earthquakes than San Francisco or Los Angeles. Its citizens face typhoons as much as people in Florida risk hurricanes, and tsunamis as destructive as those that threaten Alaska or Hawaii.

Delivering any illusion of water control in these circumstances is an extraordinary challenge, one that has accompanied Japan for centuries. Indeed, Japan is one of the few developed nations that exhibits a long history of adaptation to these unusual conditions. Its history is on display in what one can see from the train: centuries of evolution in a remarkable environment.

As the bullet train sped through the glistening countryside, I wondered how these layers of water history – the paddy fields, constructed wetlands and more – would behave when marshalled to defend Japan from a changing climate. Would that history reveal itself to be an ally? Or would it fail, proving that modern infrastructure is the only answer? As the frequency and intensity of storms, droughts and floods change, what does the resilience of the past tell us about the challenges of the future?

These would have remained jetlag-fuelled musings had it not been for the events that unfolded only a few weeks later.

On 29 June 2018, three weeks after my train ride, Prapiroon was born as a tropical storm east of the Philippines, 400 nautical miles south-southeast of Okinawa. It headed west, then veered north, as these storms often do, aiming for Korea and Japan. Three days later, on 2 July, it had grown into a typhoon. Over the following three days, climate change conspired to turn Prapiroon into one of the most destructive typhoons to ever hit Japan.

The Arctic had been unusually warm that summer – an event widely attributed to the increasing temperature of the planet. This had an unexpected effect. Ordinarily, weather in the mid-latitudes – the latitudes of New York or Hokkaido – is a sequence of high- and low-pressure systems, roughly 1,000 km wide, slowly drifting from west to east across our weather maps. That summer though, high temperatures over the polar region halted their parade in the Pacific, turning them into standing waves, ridges and troughs in the atmosphere that produce persistent, immobile areas of high and low pressure.

Other moving air masses tend to interact with these standing waves as if they were actual mountains and valleys. As Prapiroon passed over the East China Sea, heading north towards the Tsushima Strait, a filament of air wrapped itself clockwise around the stationary high-pressure centred north of Japan, flowed around it, reaching Prapiroon from the southeast, drawing moisture from the warm water of the south and rapidly fuelling its core.

Everybody was caught by surprise as the skies of southern Japan came crashing down

By 3 July, Prapiroon, strengthened by the added moisture, was just west of Kyushu, ominously skirting around Japan’s southern prefecture. By 4 July, it entered the Sea of Japan, east of Korea. As it moved northward towards Hokkaido, it pushed against the stationary high pressure to the north, squeezing against the mountain of air. Updrafts lifted ever more water into the atmosphere. Climate change and Japan’s unique water geography had conspired to create a perfect storm. On the fifth day of July, it started to rain. A lot.

Torrential rains overwhelmed the country. Everybody was caught by surprise as the skies of southern Japan came crashing down. The reports of the Meteorological Agency read like a blow-by-blow war bulletin. Soils were already saturated due to a wet June. By the end of that first day, floods and landslides had multiplied. On 6 July, the Meteorological Agency issued emergency evacuation orders for more than 2.5 million people. A further 4 million were advised to follow. From Shikoku in the west to Honshu in the east, almost 2 metres of water dropped from the sky.

When the authorities gave the order to evacuate, many were caught unprepared. Most people did not know where to go or ignored warnings. Roads went under water. In some areas, floodwaters reached 16 feet, forcing people to scramble for the roofs. The hardest hit, Hiroshima and Okayama, cut utility services almost immediately. Some 300,000 homes lost water supply and electricity instantly, as supermarkets ran out of food.

On Sunday 8 July 2018, as waters receded, Japan’s then prime minister, the late Shinzo Abe, warned of ‘a race against time’ to rescue survivors. The evacuation was difficult, as one of the richest countries in the world resorted to jerry cans and portable toilets to assist its own citizens in makeshift refugee camps. Many faced sanitation and heatstroke problems.

When it was all over, more than 8 million people had been told to evacuate across 23 prefectures, and 225 had lost their lives. By September, insurance companies had paid more than 60,000 claims. Insured losses amounted to $2.5 billion, and the total economic costs neared $10 billion. A wealthy, powerful nation had been rattled to the core.

So far, this has been the modern story of this typhoon. But when Prapiroon poured water over countless paddy fields and wetlands, it also crashed into some of the most universally recognisable, historical features of the country’s water landscape. The force of water awakened Japan’s past, as countless rice farmers bore the brunt of the typhoon’s force.

Rice is Japan’s primary staple and depends on plentiful flowing water. It came from afar, from the middle Yangtze valley, where it was domesticated possibly before 5,000 BCE. It then spread into the Korean peninsula, crossing from there into Japan around 300 BCE. With rice, Japan’s landscape went through a profound water transformation. Swamps and flooded marshlands turned into productive fields, and eventually into paddy fields. As the population grew, hills and mountains were converted too. But because sloped terrain cannot hold the depth of water needed to grow rice, streams were transformed into terraced paddies, giving rural Japan its characteristic landscape.

To prevent armies from covering great distances on foot, rivers were left shallow

Then, in the 8th century, Japan’s political system began to evolve towards the rise of the shogunate in the 12th century, by which time power was divided: Kyoto was the seat of the Japanese emperor, but the shogun – the government’s principal executive – was based in Edo (today’s Tokyo). This division of power belied a deeply fractured country. For centuries, much of the nation was ruled by feudal lords, each with their own army of samurai, the famous warrior class. The landscape reflected this fragmentation. In theory, all land in Japan belonged to the emperor. In practice, the roughly 300 lords held all the power. Peasant farmers had rights to cultivate certain plots, if they paid their taxes as a large fraction of the rice yield.

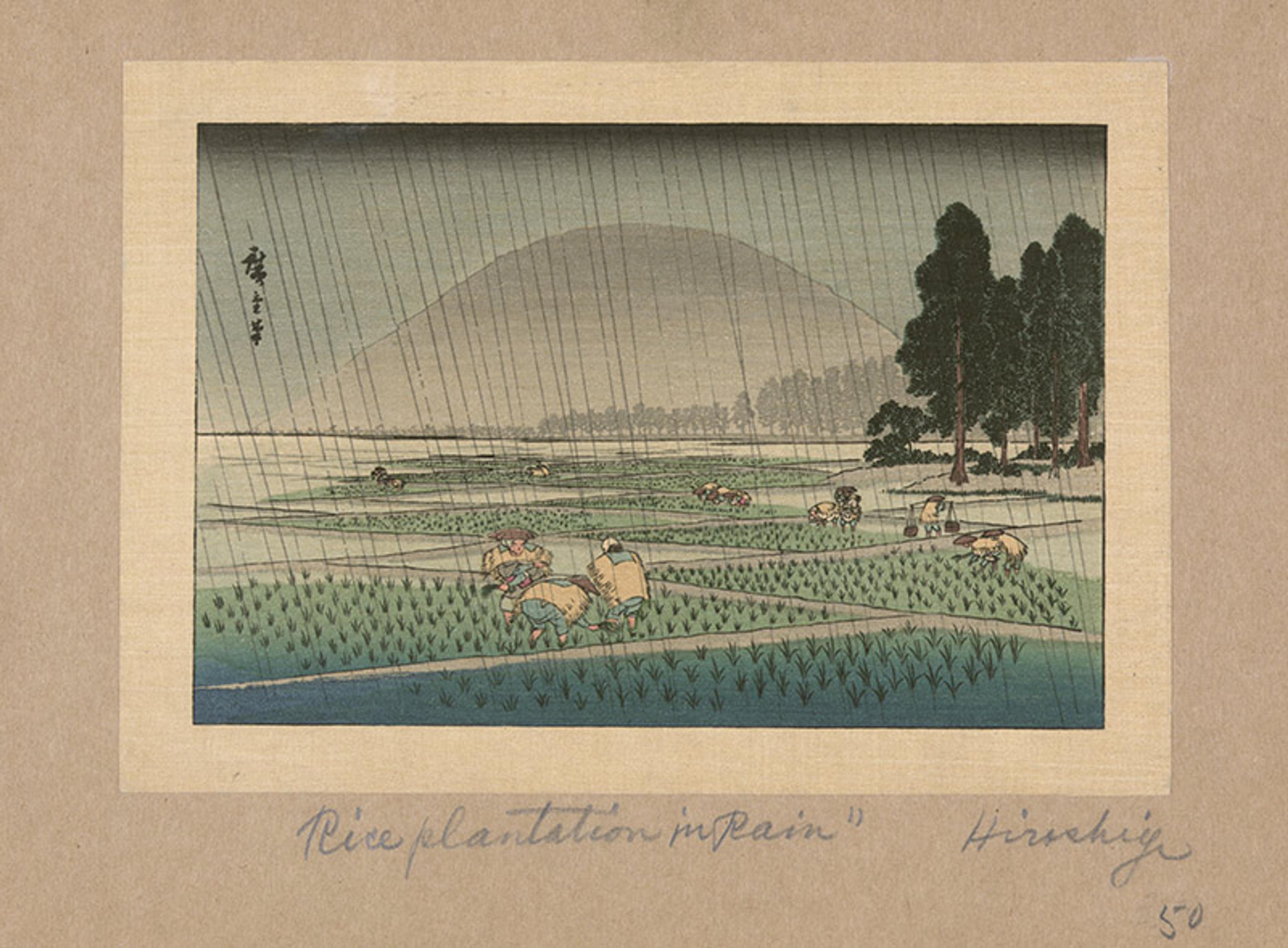

Fukeiga, Rice Planting In Rain by Utagawa Hiroshige. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Because much of the military resources was in the hands of the feudal lords, the shogun needed to protect himself by pre-empting any large-scale organised military campaigns. To prevent armies from covering great distances on foot, rivers were left shallow, unnavigable, unfit for transport, and the construction of bridges was forbidden: the only option for crossing was to do so on someone’s back. Thus, Japan committed to centuries of landscape fragmentation.

The product of these economic and political processes over centuries – over a millennium, in this case – are the many small, intensively cultivated patches of land that Prapiroon encountered on its way to wreak havoc. Rice farmers were the first victims of the 2018 floods and suffered some of the worst impacts. Around Hiroshima, for example, 90 per cent of paddy fields were destroyed. In Japan, water had created the opportunity to build a rice economy, supporting the country’s development over time. That same development also set the stage for Prapiroon’s first victims. Today’s impacts were not just a failure of modernity: they were the consequence of choices made long ago.

Not everything in Japan’s historical relationship with water was overwhelmed by the typhoon’s wrath, however. Kyoto, the ancient capital, told a different story, one that dated from the 17th century, when Japan fell under the powerful Tokugawa Shogunate. At the time, the country’s economy began growing, becoming more integrated. A wealthy merchant class emerged. Land holding concentrated. Wealthy farmers turned into moneylenders, acquiring the rights to land by providing mortgages to impoverished farmers. Capital accumulation made the first investments in infrastructure possible.

The shogunate encouraged trade, particularly with Vietnam: mineral resources from Japan in exchange for silk and other goods from Asia. As a result, the port of Osaka became a strategic coastal centre. But Kyoto, which sat upstream of Osaka, could not benefit from the port’s success because its rivers, as most rivers in Japan, had been left too shallow to navigate. At best, timber could float downstream. Everything else had to be carried by road.

Suminokura Ryoi – a wealthy 17th-century Kyoto entrepreneur, who came from a family of moneylenders and doctors – knew that improving fluvial infrastructure would allow him and others in Kyoto to capture the wealth flowing towards Osaka. He had money. He transformed the city.

Kyoto’s ability to deal with nature’s onslaught was a consequence of investments made three centuries earlier

First, he cleared a segment of the Katsura river that runs through Kyoto, allowing for the transit of flat riverboats. In a significant feat of civil works, he then forced the redirection of the Takase to join with the Yodo and run through the centre of Kyoto parallel to the Kamogawa. The resulting channel allowed timber, firewood, charcoal and other goods to be transported to and from Osaka. Then, he opened the Fujikawa River and the Kamogawa waterway. Suminokura’s investment was amply paid back by the concession of shipping rights he acquired from the emperor, which gave him the monopoly of this infrastructure. Suminokura’s projects amounted to a re-plumbing of the city of Kyoto and the surrounding landscape.

In water security, ‘path dependence’ is pervasive. But path dependence – the fact that the present is highly dependent on choices made in the past, under different conditions – does not necessarily lead to vulnerability. The unintended consequences of past decisions are not always bad.

When the flood waters of 2018 washed downhill, Suminokura’s canals provided routes that drained the city of water, ensuring it remained more or less unscathed. Kyoto’s ability to deal with the onslaught of nature had been the consequence of investments made three centuries earlier, and which had begun with a re-engineering of Kyoto’s rivers to serve the city’s economy. That re-engineering had turned into a safety valve that helped protect it from harm.

In 2018, Thailand earned naming rights for the typhoon. It was an extraordinary coincidence that they chose to give it a name of great consequence for its victims. Phra Phirun was the Thai god of water, rain and the oceans. In the ancient Vedic text of the Indo-Aryan tradition, the Rigveda, he is Varuna, the god responsible for providing water to animals and crops, a divinity that made its way into Japanese Buddhist mythology as Suiten, Varuna’s Japanese name.

Suiten was then absorbed in the Shinto tradition, Japan’s indigenous belief system, with the name Suijin. The continued reverence for this divinity in Japan – and for the related Ryujin, the dragon god of the sea – is testament to the fact that water is central to Japanese identity. It is the same cultural role that made water a favourite subject for Ukiyo-e, the woodblock printing genre that enjoyed great fortune during the Tokugawa Shogunate, producing some of the most iconic images of Japanese art, such as the celebrated 19th-century print The Great Wave by the artist Hokusai.

During the last centuries of the shogunate, the sophistication of Japan’s relationship with water grew alongside its aesthetic fascination for this existential substance, setting the stage for the country’s modern landscape as a mix of historical and modern infrastructure. Again, Kyoto’s story illustrates the profound path dependence of this extraordinary journey.

Suminokura’s 17th-century canal system played a central role in Kyoto’s economic efflorescence, becoming a springboard for subsequent industrialisation. Eventually, Kyoto’s vibrant textile industry transport needs outgrew the canals that Suminokura had built. If Kyoto was going to take advantage of global markets, it needed more and larger transport infrastructure. But, for that, it needed more water.

An entrance to one of the tunnels of the canals that connect Lake Biwa with the city of Kyoto, Japan, c1919. Photo by George Rinhart/Getty

Lake Biwa, about 15 miles east of Kyoto, was a 4 million-year-old tectonic lake that could provide water to increase navigability in Kyoto’s waterways. The question was how to take the water over, or through, the mountains that separated the great lake from its potential uses.

While damaged, Kyoto’s canal system allowed the floodwaters of 2018 to flow through the city

Discussions about a Biwa canal had been ongoing since the 12th century, but nothing had come of them, as the project seemed far too expensive. Then, the 1867 International Exposition in Paris fuelled a Western craze for everything Japanese – potentially an enormous market for Kyoto’s textiles – and the economic incentives to capture that opportunity became too strong to resist. The time for the Biwa Canal had finally come.

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, power was re-centralised away from the shogun into the hands of the 16-year-old emperor, Mutsuhito. The Meiji government committed to modernising the country, abolishing feudal domains and the samurai class. Ownership of all farmlands was given to farmers, whose names were inscribed on title deeds. People were free to buy, sell and mortgage real estate, creating a modern market, in this land of water.

The fifth article of the Charter Oath with which the imperial family was restored to government declared that ‘knowledge shall be sought throughout the world in order to promote the welfare of the empire.’ Western experience was making its way into the country. For example, in 1882, Ito Hirobumi, who would become one of the most prominent prime ministers of the age, travelled to the US and Europe to study local constitutions, selecting the Prussian model – limited parliamentary powers and a powerful emperor – for Japan. The same happened for water.

In 1888, the Japanese engineer Tanabe Sakuro visited the hydropower station in Aspen, Colorado in the US. At the time, hydropower was the new, dominant generating technology, making rivers the blueprint of industrialisation. In the late 19th century, this technology was in its infancy, but Tanabe’s gift must have been foresight. He proposed a canal to connect Lake Biwa and Kyoto, incorporating Pelton wheels to harness its hydropower. Under those terms, a scheme that had always seemed impossible – the Dutch consultant Johannis de Rijke doubted it could ever be financed or the costs recouped – became viable.

Tanabe was awarded the direction of the project. He created a modern integration of water control, transport infrastructure and energy generation. To overcome the mountain ranges that sat between the lake and the city of Kyoto, he designed three tunnels – one of them the longest in the world at the time – dug using a mix of ancient Japanese and modern Western technology, so that wooden canal boats transporting rice and other goods came down from the lake. By the early 20th century, the project generated enough electricity to bring streetlights and streetcars to Kyoto, powering its mills.

Delivering security means recognising the dialectic relationship that all generations have had with water

Tanabe’s project was the beginning of Kyoto’s hydraulic transformation. It introduced an idea of landscape that Tanabe had seen in the Western US, and kicked off Japan’s water modernisation, integrating its past with the future. By the time the 2018 floods happened, the country’s Water Agency in Kyoto had at its disposal the legacy of centuries of infrastructure development: the historical infrastructure, legacy of Suminokura’s 17th-century canals, and the modern infrastructure that had begun with Tanabe’s projects.

The stock of landscape interventions had increased the resilience of Kyoto. While damaged, Kyoto’s canal system allowed the floodwaters of 2018 to flow through the city, leaving its buildings mostly unscathed. Prapiroon hit the city hard – Kyoto was one of the heaviest-hit prefectures – but the infrastructure that made Suminokura rich and Tanabe famous contributed to saving Kyoto.

Japan’s experience, so evident in the landscape that entertained me as I travelled through the country in early June, turned out to hold a crucial lesson. Water comes from the sky; it comes from the sea; it flows over land. When it does, delivering security means recognising the dialectic relationship that all generations have had with water. Japan’s story reveals just how profound that dialectic is, how deep its roots are, and how unexpectedly consequential it can be. Most countries have forgotten their water past. But hidden behind the dams, levees, canals and countless wetlands and fields that have replumbed the world in the past century lie deep, complicated grooves: the foundations of contemporary water security.

Below the surface, Europe’s landscape still bears the scars of choices made over millennia. Italy’s northern plains drain water along canals designed by Roman farmers, medieval monks, or dug by the Venice Republic during its inland expansion. It is this dendritic, historic system that feeds – or starves, as the drought of 2022 in the Po River has so plainly shown – the grains and vines grown here today. The German villages that, in the summer of 2021, were tragically engulfed by the Ahr, a tributary of the Rhine, were settled centuries ago, when proximity to the dangerous river was a matter of economic survival.

The mid-stem of China’s Yellow River travels 10 metres above ground. Thousands of years of hydraulic control on the Loess Plateau have forced the river to flow ever faster, scouring sediment and dragging it downstream. When the latter eventually settles, accumulating on the riverbed, it condemns China to build ever-taller levees to chase its Mother River as it rises towards the sky. And the great Mississippi, Old Man River, exists as the lymphatic system of the plains that once supported complex civilisations, whose legacy of corn and maize cultivation seeded America’s breadbasket.

Japan’s lesson is universal: vulnerabilities and solutions develop – sometimes unexpectedly – over long periods of time. A society’s survival depends on protecting itself from the first, and taking advantage of the second. When it comes to its functional role in society, the landscape spans both space and time. Its hydraulic design, which emerges over successive generations, has no single planner, but constitutes a complex, sophisticated infrastructure that is inextricable from society.

As nations face a renewed fight to confront the overwhelming power of water in a changing climate, it is essential that they recognise their evolving relationship with water. We are bound to history through our inescapable dialectic with water. We dance with water over time. And it is a dance that matters a great deal.