The ecology of arid Australia is patient. The crust of this island continent, moving ever so slowly, consists of soils that are ancient, dry and nutrient-poor. Inland, water is elusive. Often exposed to soaring temperatures, the earth bakes. The forms of life that thrive here – thrifty, tough, strident, brittle, and fragile – grow to the boom-and-bust rhythm of the desert: the flourishing of the wet season, the dormancy of the dry. This is an ecology shaped by the movements of deep time, managed through more than 65,000 years of cultural practices, and battered in a few violent centuries following European invasion, pastoralism and mining.

At this meeting of slow, ancient ecology and fast settler-violence, enduring legacies are forged. These legacies play out in a myriad of ways, sometimes even altering our DNA. In certain places, humans and minerals have become irreversibly linked, as mined and processed materials travel down rivers, drift across borders, enter lungs, seep into flesh, and settle in bones. These toxic minerals scribe extractive histories into bodies through the corrosive powers of neurological interruption and developmental deformity, weaving themselves into future generations as they pass through placenta walls. It is a toxic inheritance. A small cost, the powerful argue, that individuals must bear. It is a kind of violence for which none can be truly held accountable. What can we learn from those who live with these disturbed and dispersed minerals, not as inert, dormant elements in a landscape, but as something closer to kin?

I want to take you for a moment to a remote mining community in the outback, more than 1,100 km west of Sydney. To get here by road, we’ll travel through mesmerising mallee scrub landscapes, follow the flight ways of crested parrots and birds of prey, and pass fleece-ridden rusted fences of vast livestock properties known as ‘stations’. We cross into the unceded land of the Wilyakali, the Wilya people of the Paakantyi/Paakantji language group. The terracotta-red earth appears. The sky grows larger. And then, the city of Broken Hill appears on the horizon.

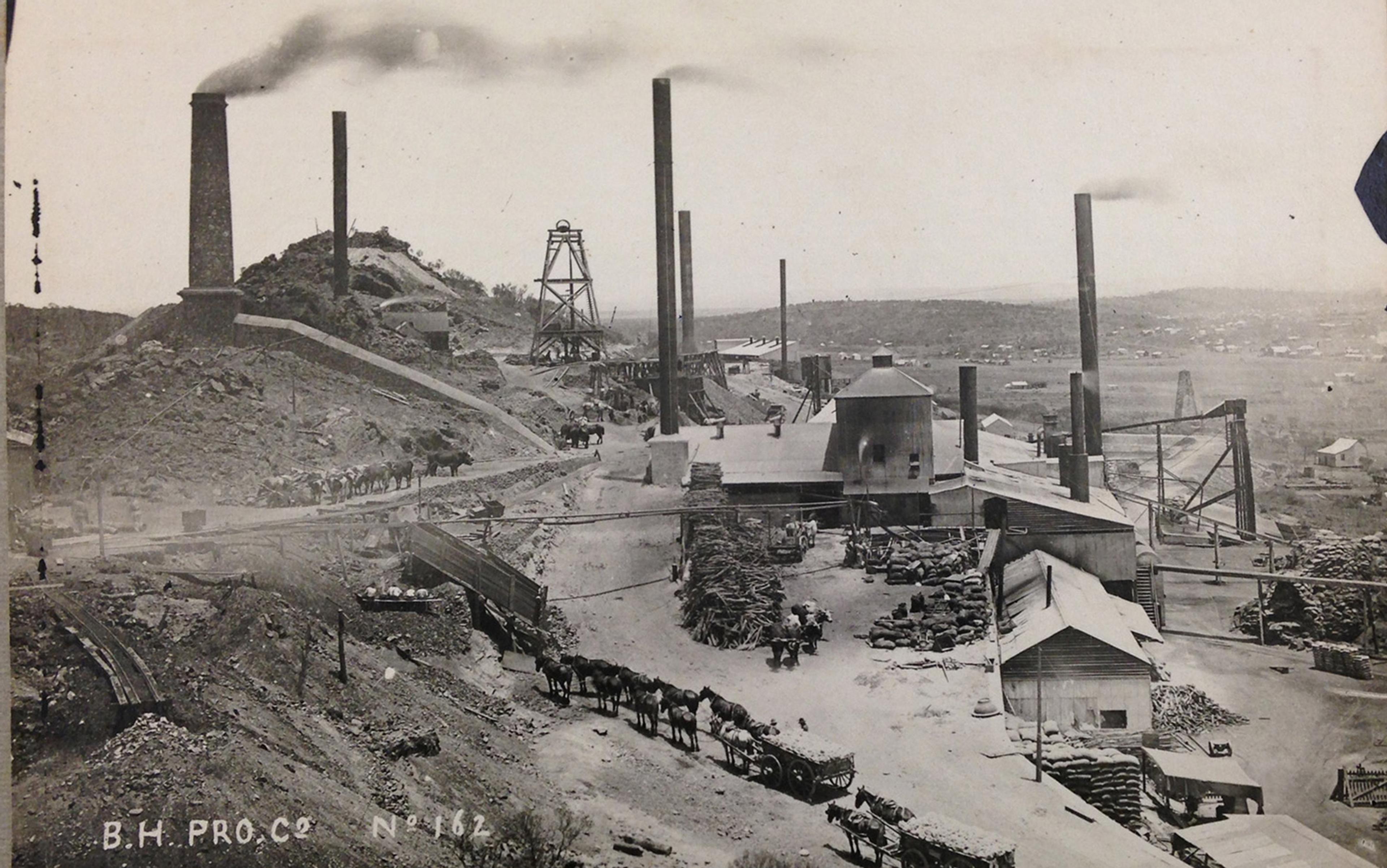

For a city with a population of fewer than 20,000, Broken Hill looms surprisingly large in the national (and international) consciousness. It is known for its mining industry, its grassroots leadership in trade unionism and industrial relations. It is the birthplace of the parent companies of some of the world’s largest mining conglomerates: Broken Hill Proprietary Limited, established in 1885, was one of the companies that became BHP; and Zinc Corporation Limited, established 1905, would eventually merge into Rio Tinto Group. It is celebrated as a setting for art and cinema: think of the Australian outback paintings by Pro Hart, or the red desert landscapes in films such as The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) and the Mad Max series.

It is also known for its dust.

By the late 1800s, large swathes of inland Australia faced an onslaught of hard-hooved animals such as sheep, goats and cattle that decimated the soil structure, induced acidity and broke the delicate webs of life that bound the crust. Introduced animals, such as rabbits, rapidly expanded in number and spread, stripping the earth bare and inhibiting regeneration by eating seeds and seedlings. Native vegetation was actively cleared by settlers at a scale the continent had never experienced. When the wind blew, it carried the earth with it.

‘As long back as I can remember, we’ve had dust storms.’ That’s how Ina Pearl Delatorre (née Hall) remembered life in Broken Hill in the early 20th century. Born in 1891, she lived in the city her entire life. When interviewed in 1982, she reminisced about how the plumes would grow: ‘I suppose it would be the dust rolling,’ she says, ‘but it looked like clouds because it was that high up.’ Sometimes, the dust was so thick it would ‘black out the light’. Sometimes, it piled up so high inside homes you ‘could shovel it out’. Dust storms blocked the sun, crept under doorways, and suffocated airways. More common than the storms was the dust that blew off the surrounding sandhills: ‘That dust would sting you … there’s a grit in it, like a gravel and, to pace that, to go against that, it would sting your skin.’

That mineral grit is the very reason Broken Hill exists as it does today. In 1883, in frontier New South Wales, Charles Rasp, a boundary rider, identified a significant ore body laden with silver, lead and zinc. This jagged geological anomaly (resembling broken hills) sparked a rapid expansion of prospectors and associated activity inland, creating more local impacts. Very quickly ‘Broken Hill’ grew to a settler population of 3,000; by 1905, the city swelled to 30,000. But this wasn’t a place that had the ability to support settler dreams. Mining operations began to drastically alter natural contours and fluvial processes, further changing the landscape, and a parched and broken ecosystem emerged, stripped of its capacity to ‘bounce back’ or contain the movement of old, unstable soils. The dust of Delatorre’s era was the land’s way of speaking back.

People understood tree-clearing was making the dust worse but the entire town ran on wood

Just as the local mining industry was booming, water provisions became stretched, and sand-drift and dust were increasingly mobilised. Each significant period of drought – 1902-03, 1925-26, 1941-46, and 1948-51 – further propelled the instability and mobility of the earth. As the historian Cameron Muir writes in The Broken Promise of Agricultural Progress (2014): ‘Australia’s cultural iconography of rural decline, land degradation and economic collapse were never associated and confined to a single “event” like the Dust Bowl of Northern America. The boundaries – cultural and ecological – are more diffuse.’

Yet Broken Hill wasn’t always devoid of vegetation. Before settlers began to use the land, the region was ‘clothed in vegetation, and supported a profusion of fauna’, as Horace Webber wrote in The Greening of the Hill (1992). It was once a mosaic of trees, shrubs and groundcovers adapted to the nutrient-poor and often-dry conditions, including robust mulga (Acacia aneura), whose roots penetrate deep into the soil to find moisture and fix nitrogen through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Mulga grew alongside other tree species including wattle, fruiting quandong, casuarinas and native white pine.

People understood tree-clearing was making the dust worse, Delatorre says, but the entire town ran on wood: ‘My first memory is nothing but horse teams and more bullock teams all day long carting wood, because everything was fired with wood.’ The pumping station, the mines, the bakers – ‘everything’ – she says, ‘was run with wood so it didn’t take long to clear around where we lived and then they had to go further out and further out.’ By the 1930s, significant sand drift and dust had made Broken Hill inhospitable and it became a threat to mining practice, profitability and the future of the industry. And so, a ‘campaign against the sand’ was launched to protect the town by re-establishing a local arid-ecosystem around the city to reduce sand-drift.

Between 1936 and 1938, a regeneration project led by Albert and Margaret Morris began to create a protective girdle of trees and shrubs around Broken Hill. ‘The Regen’ as it is affectionately known, is now celebrated as one of the earliest examples of ecological restoration in the world. My own relationship with Broken Hill was cultivated through doctoral research on these regeneration reserves. I found much more than a feel-good pro-environmental conservation tale. Rather, the Regen was a palimpsest of both positive stories of human ingenuity and nature regeneration, and what the archaeologists Bjørnar Olsen and Þóra Pétursdóttir in Norway call ‘unruly heritage’: the messy and often overlooked manifestations of the afterlives of waste.

Mammoth sun-blocking dust storms still occur, like in 2009, and again in 2018 when dust clouds smothered much of New South Wales, reaching as far as the eastern seaboard and enveloping Sydney. Stories of these storms continue to be told, but there are less obvious stories in Broken Hill, too – of the slower migrations of sand drift and dust laden with lead. It is well understood that exposure to lead-heavy dust can cause poisoning or death, or interrupt foetal and postnatal development due the presence of a neurotoxin. During my first pregnancy, while I was still studying, I chose not to return to Broken Hill to avoid the risk of exposing my unborn child to an unknown level of environmental toxicity. I didn’t want to breathe in the dust. I was uncomfortable explaining this decision to those who called the city home, those bound to the legacies of extractive mining. Not everyone has the option of leaving. But some of those who can leave, and do know the risk, choose to stay. Lead is a familiar reality that makes up just one strand in a complicated interweaving of people, place and industry. But how do people make sense of their relationship with this dangerous mineral that has become neighbour, that has become kin? And what are the politics and practices that have enabled some degree of resignation to this toxic inheritance?

Lead has been mined in Broken Hill since 1884, and the health risks have been understood for almost as long. Lead poisoning, or ‘plumbism’ as it is also known, was evident among the early miners and their families. Seven years after lead mining began, a Broken Hill doctor wrote about the ways that lead ‘attacked’ the young and old. ‘Those who are engaged at the smelters are affected almost as frequently and with nearly the same virulence as those who work underground,’ he wrote in the local paper, The Barrier Miner, in 1891. ‘The orepickers and sorters, who are usually children, are liable to fatal attacks.’ The poisoning first shows itself in convulsions, and ends in coma and death.

Miners, c1907. Courtesy the State Library of South Australia, B 54756/38

Some of the men killed by lead poisoning are memorialised among the more than 800 miners who lost their lives in the mines. Their names are listed inside the towering sculpture that sits atop the Line of Lode, the mined-out remains of the ‘broken hills’ cutting through the centre of town. I scan my eyes over names from 1884 and read a few aloud. ‘James Hendy Johnson: Lead Poisoning’; ‘Joseph Henry Pearce: Lead Poisoning’; ‘Ernest H Sweet: Lead Poisoning’. But these names are just the tip of an iceberg in a sea of soil and sand.

The first inquiry into Broken Hill’s lead poisoning was launched in the early 1890s by the New South Wales government. But ‘as a result of industrial conflict’, writes the historian Hannah Forsyth in 2018, the inquiry ‘chose to draw no conclusions’. The Report of Board Appointed to Inquire into the Prevalence and Prevention of Lead Poisoning at the Broken Hill Silver-lead Mines (1893) gives a thorough 162-page account of the issue of lead poisoning. Other reports followed. In 1914, the Royal Commission into mining in Broken Hill considered the health impacts of lead, while another by the New South Wales Government in 1921 reported on wider health impacts of mining. Such inquiries outline in detail the dangers of lead poisoning to mine workers and the wider community. In 1920, in a Federal parliamentary debate, the member for Barrier Michael Considine described the mining dividends as ‘wrung out of the corpses of the miners and of their children’.

A thin veneer of dust settles on everything – play equipment, windowsills, growing vegetables

While industrial conditions would improve over time, immediate changes to protect the workers and the community were repeatedly stymied to protect industry profits. As described in The Barrier Miner on 21 September 1894:

A Government board of inquiry sat and took evidence, and found that we were being poisoned and that the poisoning was preventible [sic]. Still the evil has only increased. The medical opinion is stronger on the point than ever it was. The women and children especially are suffering; the doctors are almost – it may be quite – unanimous in declaring that Broken Hill is becoming a place unfit for a woman, and a married woman especially, to live in. The cry that has saved the companies – the Broken Hill Proprietary Company almost exclusively – is that we would be unwise to do anything which might hamper the industry which supports the town.

Broken Hill’s unique toxic conditions were exaggerated by water scarcity. Water shortages in the late 1800s and early 1900s led to harsh conditions, disease and high child mortality in the city. Lead dust that settled on roofs was washed into rainwater tanks, poisoning the humans and animals who drank it or washed in it. One resident who lived through that era, Les Crowe, reflected on the critical state of water shortages in his childhood during an interview with the social historian Edward Stokes in 1982. Crowe was born in Hawthorn, Victoria in 1890 and moved to Broken Hill at the age of three when his father began working the mines. He used to protest having to bathe in the same dirty tub of water that his mother had washed the clothes in each week. ‘Come on Les, it’s your turn,’ she’d say. ‘I’m not getting in that bloody dirty water,’ he’d reply, ‘you’ve washed the clothes in it and the rest of the family’s had a wash and a piss in it… I’ll wait ’til you wash next week.’ But, he adds, you ‘didn’t waste a drop of water – oh no, crikey.’ Crowe also remembers laying his father down on the floor of their home as he convulsed from fits caused by lead poisoning. It was incurable: ‘Once you got leaded, they couldn’t clear it.’ His father eventually died. It was not an illness that stayed silent or underground. Other people remember witnessing fits on the streets of Broken Hill.

You won’t see convulsions on the main road anymore, and the contemporary industrial conditions are much improved, but the ongoing health effects are still hideous, mostly irreversible, and unevenly distributed among the city’s population. The young, the poor and the Indigenous community have a heightened exposure to risk, mostly caused by improperly maintained rental buildings near contaminated sites. A thin veneer of dust settles on everything – play equipment, windowsills, growing vegetables – and washes into water tanks. Even now, children are still becoming sick from ingesting lead. Signs in public parks remind kids to wash their hands, and public health advice suggests avoiding homegrown food and rainwater that might be contaminated. High lead exposure is also linked to toxic skimp dumps. These piles of contaminated residue from smelting operations persist around town on parcels of land with often complicated land tenures, which confuses authority and responsibility. For example, a skimp dump in the south is within the boundary of a mining lease, adjacent to a school, and within the heritage-listed regeneration reserve. There are no signs marking the dumps. Frail fences cordon them off, and brittle caps, weathered by the elements, partially cover them. They make great bike jumps. Spinning wheels kick contaminated dirt into the faces of children who play on them.

The dust still moves, although recent efforts by public environment and health agencies have attempted to slow it. But some impacts are difficult, nearly impossible to arrest. Lead can migrate from the bones of pregnant women into their growing babies, passing toxicity onto yet another generation. Then later, as bones begin to calcify after menopause, lead stored during childhood can release back into the bloodstream. Sometimes, the effects are so gradual or delayed that those suffering are unable to connect cause and effect. And the causes are everywhere. It is almost impossible to identify contaminated material when it resembles normal desert sand. Any exposed earth is a potential threat.

In the 1970s, a mountain of lead mine tailings towered over southern Broken Hill. Some locals from that era told me that they assumed Mt Hebbard was a natural formation. ‘But natural hills may not be natural hills,’ one resident reflected, ‘you just don’t know, do you?’ Wayne Lovis, who helps manage the Regen and other greening projects in Broken Hill, grew up in its shadow. The locals called it a mountain, he says, because it ‘went right up into the sky, past the clouds – it was huge.’ And when the wind blew ‘you could see the dust trailing off of it’, spreading a fine haze of lead particles across the city.

Once mobile, tailings look just like sand and disperse widely, making identification, containment and any attribution of responsibility near-impossible. Lovis reminds me that lead isn’t the only problem: there is also the suite of toxic chemical used in the mines: ‘the xanthates and all of that… God knows what else.’ One solution involves carefully capping tailings. But when caps are broken or exposed through erosion, the wind blows Broken Hill’s toxic inheritance across the city’s streets, into nearby schools and kindergartens, and eventually into bodies and bones. ‘We’re all lead-heads,’ says Lovis, ‘all lead-affected.’

The way that locals understand their relationships with contamination has arguably been made possible by powerful corporate narratives. So the environmental scientists Louise Jane Kristensen and Mark Patrick Taylor wrote a paper called ‘Unravelling a “Miner’s Myth” That Environmental Contamination in Mining Towns Is Naturally Occurring’ (2016). Their work highlights the myths created and disseminated by industrial operators to ‘distract the public and the authorities away from understanding and determining the true source and cause of environmental contamination’. These myths attempt to excuse current mining operators by making claims that place the blame elsewhere (or deny there is a problem): if the problem is just dust, they seem to be suggesting, why don’t you try cleaning more?

Mascots such as Lead Ted, a friendly teddy bear, guide locals on living safely with their toxic neighbour

In Broken Hill, such myths normalise daily relationships with toxicity and shift responsibility on to unassuming locals – especially women. In an interview with a local resident, Sarah Martin, I learned that the message from the Broken Hill Environmental Lead Centre in the 1980s was broadly understood as: ‘If your child has got high lead levels, then you’re a dirty bitch.’ In this way, industry partners consistently abdicate their responsibilities to those affected by the consequences of wealth extraction: the people living in contaminated communities. Importantly, these myths are not only pushed by industry, they have also made their way into public consciousness, have shaped public policy, and have been taken as truths by government departments.

Generations of locals have witnessed repeated waves of lead awareness campaigns and grown up with mascots such as Lead Ted, a friendly teddy bear who shares health advice, guiding locals on how to live safely with their toxic neighbour. Efforts to more actively address health concerns have depended on public pressure and inconsistent public funding. Between 1994 and 2001, a multifaceted intervention reduced the blood lead levels of locals by two-thirds, but, in 2014, 53 per cent of children in Broken Hill still had lead levels exceeding 5 µg/dL, the draft National Health and Medical Research Council blood lead reference. Through local narratives and sheer necessity, residents are left to laugh about being ‘lead-heads’ as they navigate the complex realities of living with a heritage site that carries a real threat of physiological disadvantage and disability, as well as persistent mental health and behavioural problems. The deep mine shafts and diverted waterways, eroded gullies and waste heaps are as much a part of the sense of place of Broken Hill as the vibrant earth, the vivid red of Sturt’s desert pea (Swainsona formosa) after rain, and the brilliant sunsets. It is for all of this and more that Broken Hill is celebrated as a ‘Heritage City’. But this affection can become a tool for manipulation.

Sometimes, the narratives constructed by mining operators and held up by an immutable sense of place work against healing efforts. A powerful demonstration of this is in Queenstown, northwestern Tasmania, which the local writer Pete Hay describes as an ‘archetypal turn-of-century mining town’. Queenstown’s rivers still run orange, and the effects of the ecological toxicity from acid-mine drainage have spread far into the nearby King and Queen rivers, which carry heavy arsenic loads. The political and cultural predilections of this mining town present a stark contrast to the Tasmanian preservationist Green movement that has rapidly grown since the 1970s.

In part because of this antagonism, locals hold a strong and proud view of their enduring industrial history. More than a century of mining and smelting operations put continual pressure on the surrounding hills, and what remains today are the iconic pale-orange hues of a lunar-like landscape largely devoid of vegetation (but still popular with tourists). In late 1993, the mine was scheduled to close soon and was required by law to conduct extensive rehabilitation works including a revegetation programme. But the desolate hills and the river’s vibrant colours had become central to Queenstown’s unique sense of place. Locals resisted and halted the remediation efforts. Some visitors see desecration, not beauty, but the locals whom Hay interviewed weren’t concerned. ‘We don’t mind them coming in and abusing us for what we’ve done in the past,’ said one person, ‘at least it keeps the town alive.’ Hay quotes residents saying things such as: ‘Everyone thinks trees are beautiful, but other things are beautiful … you should see the colours in the rocks on a fine summer sunset.’ Or: ‘If the reveg goes ahead, this’ll be just another town with no real attraction.’

A strong sense of place does not necessarily correlate with pro-environmental values. Sometimes we are pushed – even coerced – into complex, intimate forms of kinship with places. Sometimes these relationships are beneficial, or benign. But sometimes they can become dangerous or deadly under the influence of global systems of capital, power and the evasion of responsibility.

In Broken Hill, what was once a locally owned industry has now come under the control of international stakeholders. Engaging less and less with the city and its residents, these stakeholders fill their pockets while lead continues to penetrate local bodies at sites of extraction and processing. But the impacts are experienced much further afield, too. Broken Hill lead has been smelted in Port Pirie, South Australia since 1889, where it has generated an enduring health crisis in the local community. Minerals from Broken Hill are shipped around the world. They are also dispersed unintentionally via atmospheric aerosol circulation: lead isotopes in polar ice cores show that Broken Hill lead smelted in Port Pirie remains a significant source of toxic lead contamination in Antarctic ice and can be detected right back to 1889. This dust reaches deep and far.

The interests of the mining industry are granted higher moral validity than human or environmental health

Health experts have characterised lead toxicity as a public concern of global dimensions. Unlike other well-known examples (such as in Flint, Michigan in the US, and Bunker Hill Mining and Metallurgical Complex in Smelterville, Idaho), there is no clear pathway to litigation or accountability in Broken Hill, a place where multiple mining companies have come and gone, where land tenures are complicated, and where the dust moves so uncontrollably. And in a city that is proud of its mining heritage (where many families were or are connected to the industry), it is hard to know where to begin. It’s difficult to know how to count the dead, human or otherwise. It is difficult to face up to the past: the role that your ancestors may have played in this. It is difficult to confront the future: the possible impacts from raising your family here. You might not have the option to go elsewhere. You might just really love your home.

This toxic, unruly inheritance is not a burden that individuals should have to bear alone. The steps, decisions and tradeoffs that have produced this reality are stowed in the archives and etched in the soil. Perhaps telling the story of this pursuit of wealth might help us rethink the sacrifices that we are willing to make in the name of extractive capitalism.

The expansion and extraction mentality of frontier, settler culture in Australia has actively worked against environmental protections, as well as the rights of miners and their families, but often most forgotten in this accounting are the rights of First Nations communities. This mentality has enabled the perpetual shirking by industry of environmental and health responsibilities, and the deflection of legacy issues to the public, to local governments and to Traditional Owners. Companies avoid closure and clean-up responsibilities, and financial bonds supposedly in place to keep them accountable are radically insufficient for best-practice remediation efforts. At multiple sites across the continent, former mining areas remain too toxic to be safely accessed, and more than 50,000 abandoned mines scatter the continent. The interests of the mining industry are repeatedly granted higher moral validity than that of human, social or environmental health – but there is resistance.

Prominent campaigns at present include those against the Adani Carmichael Coal mine in the Queensland Galilee Basin on Wangan and Jagalingou Country, and against the expansion of the McArthur River Lead-Zinc mine in the Northern Territory, which will impact Gudanji, Garrwa, Marra and Yanyuwa peoples. These are battles to address the global and local impacts of emissions, as well as issues of environmental justice. In Australia, rocks and landforms that have been scalped and sliced have always been part of ‘Country’, the Australian-Indigenous term that denotes the sentient, epistemological and cosmological reality of the world. ‘Country is alive,’ writes the Palyku writer Ambelin Kwaymullina, ‘and more than alive – it is life itself.’ If Country is sick, so are its people. By making visible the oftentimes invisible legacies of mineral manipulations, and by paying attention to the histories and agency of toxic materials, perhaps the future may be called to be a little more just. We are all implicated in these relationships, even if they have not yet written themselves into our cells.

This is a story of just one place where mining myths fall apart, and settler dreams beget scarred Country, sickness and death. The urgency of attention and response is only heightened by the impacts of exaggerated environmental extremes wrought by climate change. During much of my second pregnancy, in Australia’s ‘savage summer’ of 2020, I stayed indoors or wore an N95 mask to protect my growing child, first from the toxic smoke of wildfires, and then from COVID-19. Around that time, we also brought in some garden soil that we later found was contaminated with herbicides, which warped and killed our vegetables. Toxic legacies are everywhere; some are just more obvious, or closer to the source. As one Broken Hill local told me: ‘It doesn’t matter what suburb of a capital city you’re in, you’re still not necessarily knowledgeable of what was there before you were there, you know, what sort of toxic dump you might be living on… you never can tell.’ She looks around, the sun beaming down on the red dust beneath our feet. ‘At least here, you’re aware,’ she says, ‘you’re conscious.’

A version of this essay originally appeared as ‘The Politics of Contaminated Kin’ in Kinship: Belonging in a World of Relations; Vol 2: Place, edited by Gavin Van Horn, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and John Hausdoerffer (Libertyville, IL: Center for Humans and Nature Press, 2021): 87-95. It appears here with permission of the Center for Humans and Nature.