Where the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean merge, a small Scottish archipelago sits barren and bald, hundreds of clumped islands of grey and green rock. Shetland is a 12-hour ferry ride from the granite port city of Aberdeen, and its population of about 23,000 stretches across one larger island and a few smaller ones that dot its shores. Even in the dead of summer, it is a cold and reclusive place. The most consistent weather is wind, which howls day and night.

While the Shetland economy benefits from North Sea oil and gas exploration and commercial fisheries, a certain old-fashioned atmosphere reigns. In summer, Lerwick, Shetland’s largest town, decorates its streets with bunting. Recently, I received a piece of mail from a Shetlander whose return address is only their last name and the town they live in. Shetlandic dialect – no longer used regularly but still heard in homes and at the pub – leaves Shetlanders with an accent flecked with Scottish and the now-extinct language of Norn, which lilts with soft syllables such as ‘da’ and ‘de’. It is a remarkable place to learn about the edge of the world.

In the mid-20th century, young men from Shetland would come of age and travel to Edinburgh. ‘Quite a lot of Shetland boys did that,’ says Gibbie Fraser, who was that boy some 60 years ago. ‘And I remember goin’ and dere was a lot of men dere and dey all seemed huge and in dose days dey all wore … dere dress clothes as almost a uniform.’ For many, this would have been their first trip to the mainland, their first trip to ‘Scotland’ proper at all, and the boys would watch the double-decker buses for the first time, or board a black cab for the neighbourhood of Leith. There, they would stand in lines that snaked around city blocks.

In a building on George Street, on the third floor, an employee of the now-defunct Christian Salvesen company would be holed away, scribbling names on a ledger. The company, then the largest whaling firm in Britain, began staffing their whaling operations in Antarctica once a year, in the early fall. ‘The way I felt myself, because of my lack of education if you can put it that way, I had to be a soldier of fortune,’ says John Alexander, a former electrician. ‘Dere wasn’t much work in Shetland,’ echoes Davie Clark weeks later, at a fish and chip shop in Brae, a town on the edge of a bay in Shetland. ‘I stayed on the island of Yell and I’ve been 37 years here, and in that period there was nae work.’ So the boys from Shetland went south.

‘Salvesen’s office was kind of along da street dere, and de men would be queuing up along da street waitin’ on jobs,’ says Alister Thomason. ‘And dey’d come oot da office and dey’d shout out a name and, mostly all de Shetland men, they’d pick dem outta de queue, dey knew dere names because somebody recommended dem.’

Shetlanders, even the least experienced, came ready for whaling, steeped in familiarity with the sea, and this, according to surviving whalers, set them apart. In his house in Lerwick, Norman Jamieson proclaimed: ‘You can get sea time just standing at the gable of the house in Shetland!’ The interior of Jamieson’s house has been styled like a fishing boat bunker. A sign on the door says he’s ‘Out to Sea’.

Shetlanders are some of the only living people who participated in Antarctic whaling. Whaling in the Southern Ocean followed the devastation of whale stocks in the North Sea around Britain, Iceland and Norway in the late-19th and early 20th centuries. Whaling has been a foundation of Shetland’s economy for more than 300 years. It began with subsistence whaling, in the 18th and 19th centuries, and then developed into large-scale Arctic and Greenland hunts in the mid-19th century. Salvesen began whaling in Shetland at Olna in 1904, when the company established a whaling station. ‘That’s where [they], I suppose in a way, came to appreciate the Shetland men,’ said Fraser.

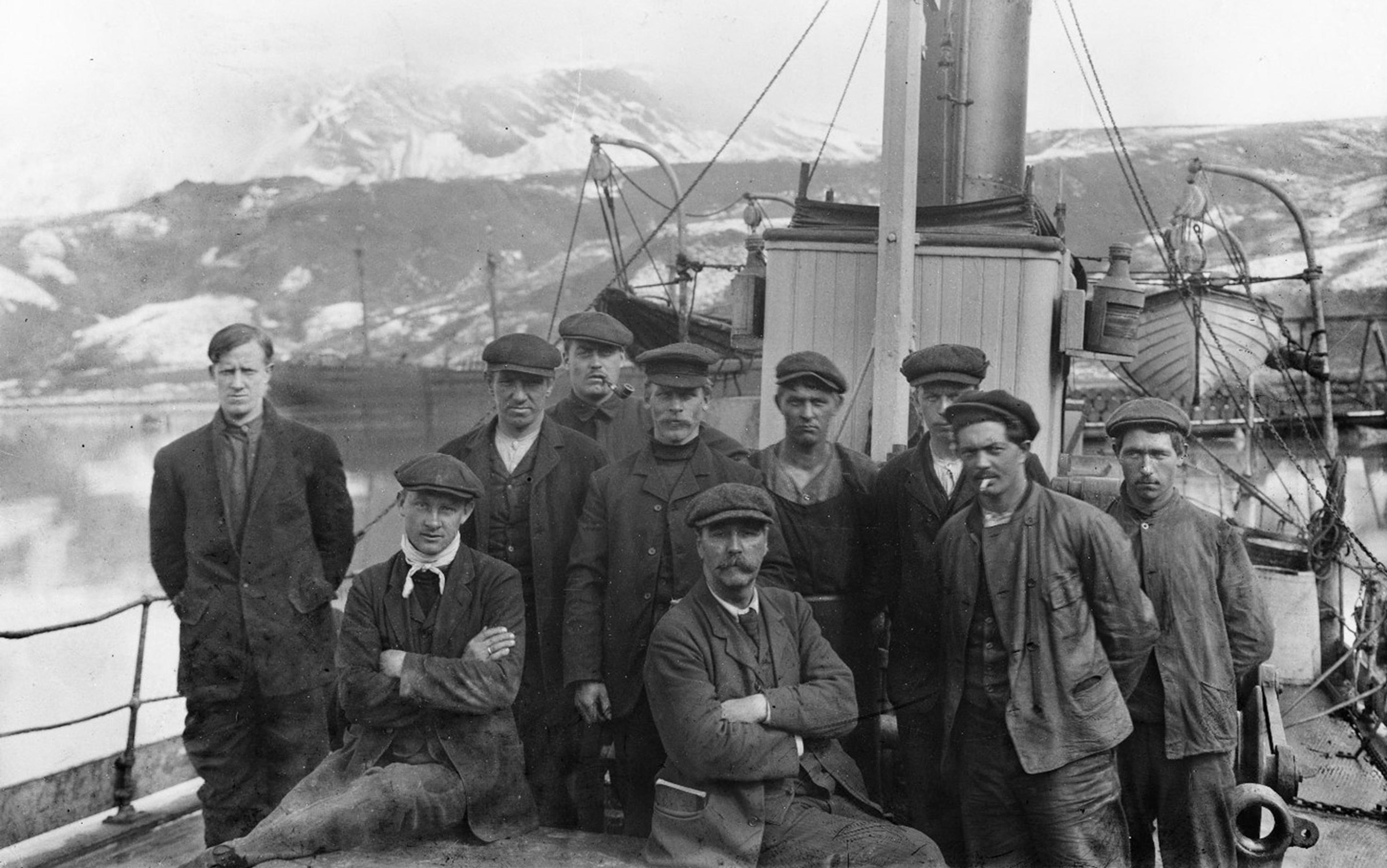

Leith Harbour, South Georgia, 1912

Heading into the 21st century, though, the utility of a whale slowly became obsolete. Fibre technologies meant plastic and nylon replaced whale bones in clothing. Advances in chemistry and electricity meant that, by the 1900s, homes were no longer lit by whale-oil lamps. By the early 20th century, northern waters became unproductive, stretched to their limits by overfishing. ‘So when this whaling died off and [Salvesen] moved to the Antarctic and Southern Hemisphere, then he asked Shetlanders to come with him,’ Fraser said. In 1909, facing down the prospect of war along with low whale-catch numbers, the British Colonial Office established a whaling base on an island in the sub-Antarctic archipelago called South Georgia, about 1,600 km east of Cape Horn off Chile. In resource extraction from the sea, so tied to seasonal cycles, the end had always been apparent, a prophecy visible in ledger books. But Salvesen still went south. In the 1930s, technology had begun to make it easier to fish in Antarctic waters – and Shetland’s men had the skills to go.

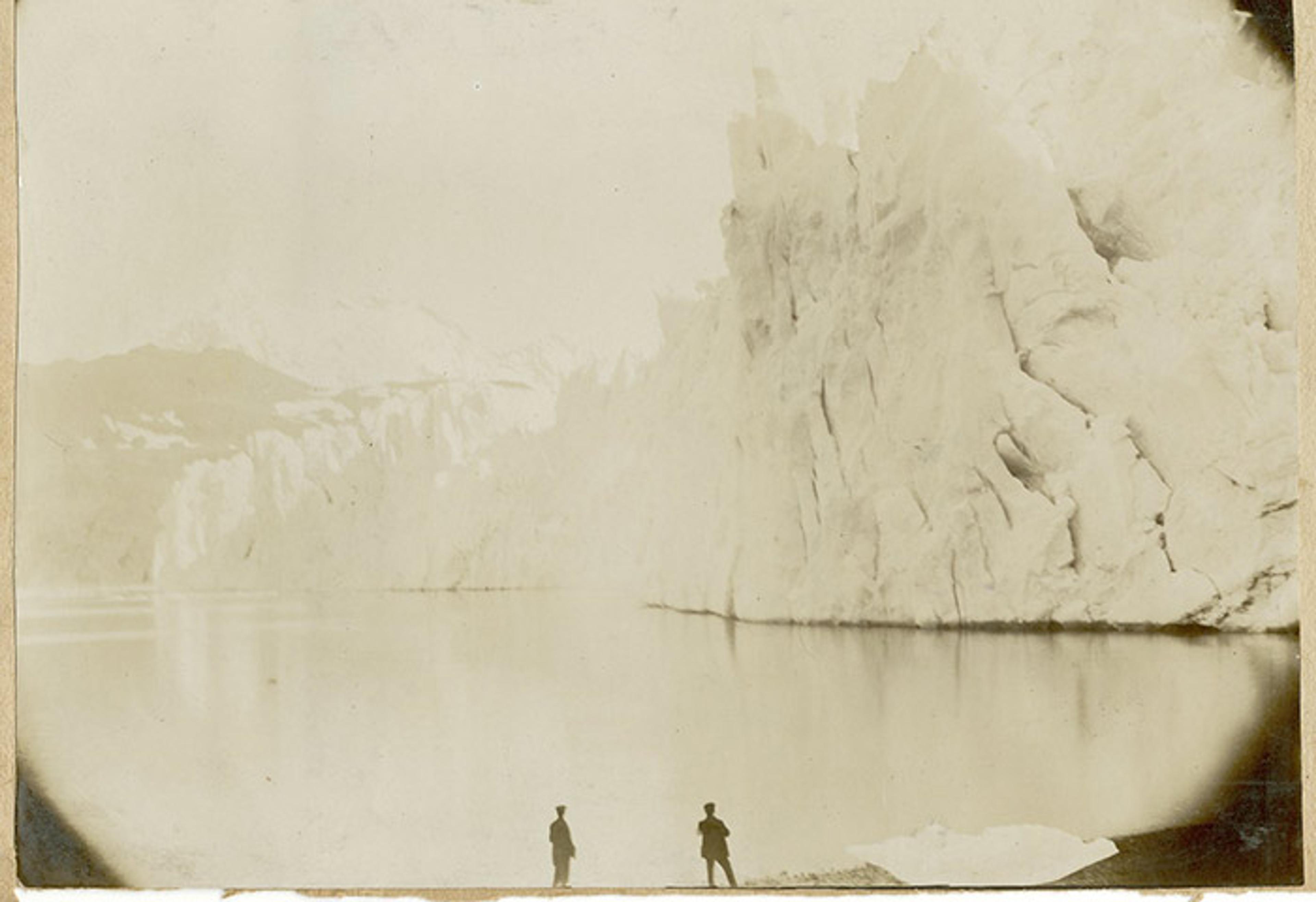

Cumberland Bay Glacier, South Georgia, 8 June 1917

Both world wars had brought an increased need for whale products. Margarine, made primarily with whale oil, replaced butter in larders across Europe, and whale-meat extract was a primary ingredient in stocks such as Bovril. Lubricants derived from whale oil were also in high demand for use in explosives and machinery repair. Even animals relied on the whale – meat and bone meal were eventually used in stock feed and fertilisers. Britain’s Colonial Office knew that they were well-primed to take the blue, humpback and sperm whales that lived in the southern seas. More than half of all whales officially harvested in Antarctica were hunted in the years following the Second World War.

All whalers landed on South Georgia, a crescent moon-shaped chunk of land four times as long as it is wide, sliced down the middle by a mountain range that slopes towards the shoreline. Geographers have described the island as ‘drowned topography’ – its bays rest on a foundation of old mountain valleys that have been flooded by the ocean. These submerged summits mean that undersea currents create a rich feeding ground for the crustaceans on which whales feed. Salvesen was placed in charge of operating the station named ‘Leith Harbour’, after the Edinburgh neighbourhood, by the Colonial Office. From Leith Harbour, whalers hunted rorqual whales such as blue, humpback and sperm whales. At the height of Antarctic whaling, Leith Harbour boasted a bakery, a hospital and a movie theatre. Britain and Norway dominated the global whaling industry, and they were able to staff their operations with experienced men.

Men would scale whale carcasses using ropes, like ice climbers with pickaxes

Commercial whaling continued at Leith Harbour until 1961; the by-products born of a whale’s body were necessary, valuable commodities. The industry ended at a time of intense industrial power that facilitated over-harvesting. As whales had been caught to the point of extinction surrounding the whaling station, all whaling eventually became ‘pelagic’ – that is, occurring entirely out at sea, where whales were chased, shot, butchered and processed on massive, 10,000-ton ‘floating factory’ ships. The mass adoption of factory ships in the 1930s changed everything about whaling and, in some cases, hastened the end of the industry itself.

The SS Saragossa factory ship c1925, later scuttled after a fire in the South Shetland Isles

Factory ships usurped the need to carry whales to shore for harvest, and worked in tandem with catcher boats, which were fast and could chase down whales and harpoon them for factory ships to later collect. Those harpoons were explosive, catching in the whale’s body before detonating a few seconds later. Catcher ships used wartime technology such as ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) radar, which would track whale movements underwater to surprise them. Factory ships had onboard chemistry labs, to ensure that the whale oil being reduced onsite was of a higher quality. The jawbones of blue whales sat often at the edge of the ship’s deck. Men would scale whale carcasses using ropes, like ice climbers with pickaxes.

The process of butchering a whale was bloody – it included hoisting a whale up onto the ship’s deck by its tail and shoving it along a slipway dubbed ‘Hell’s Gates’. Workers would ‘flense’ the whales, separating blubber from muscle using long, curved knives. A whale had to be shot, flensed and off the deck of a ship within five hours. Flensed whale blubber was fed through a hole into the steamers below, where it was melted into oil and inspected for quality and purity. The rest of the whale was then methodically chopped up. Muscle and bone was mulched into meat meal, and packed into barrels to be sent home. Even the guts were inspected, for ambergris – a valuable, mysterious chunk of the stomach that’s used in perfume manufacture. Very little of a whale was left behind.

Soon, the overfishing that depleted whales near the coasts would drastically reduce the populations of blue and sperm whales in the waters surrounding Antarctica. By the 1950s, many whaling officials conceded that Antarctic whaling was operating on borrowed time. Whaling, then, fell squarely into what the scholar Arthur McEvoy in 1986 dubbed ‘the fisherman’s problem’, a paradox: overfishing would lead to the end of the industry, but there was no reward for restraint. By 1963, the British abandoned whaling in Antarctica entirely, because the combination of overfishing and regulation via the International Whaling Commission had made it unprofitable.

In the summer of 2017, I interviewed Clark and 10 other Shetland whalers for my postgraduate dissertation. Their lives shared some distinct patterns. Almost all had learned of Antarctic whaling from their families, who in many instances had anchored themselves first to North Sea whaling with Salvesen. Almost all of them had headed to Edinburgh at 16 to get their first job, starting as mess boys on whaling ships, then working their way up. ‘When you think about de whaling, whaling was far more in tune with de Shetland way of life than going in de merchant navy,’ said Fraser.

‘All dese men was always going away from Shetland,’ said Dan Thompson.

‘Yeah, dey was always goin’ away,’ said Alister Thomason, sitting next to him.

‘Always … Men was away for long periods.’

‘There weren’t any other options. And I think people thought it was a very hard life, a lot of hardship, but bein’ brought up in Shetland I think we were quite capable of dealing with hardships.’

A season spent in Antarctica took place from early fall until April. Technically, each contract required men to ‘over-winter’ – spend the off-season in Leith Harbour – every three years. But there was never any need to enforce this rule. Men would volunteer to over-winter in droves for the extra cash, spending their time repairing machinery, cleaning and maintaining buildings. In extreme cases, some men would go close to three years without coming home at all, stacking contracts back-to-back.

General view towards South Georgia, 1928

Life in Antarctica took place either on shore, on a ‘floating factory’ ship, or aboard a catcher boat. Clark remembers catching what he believes was the largest blue whale ever caught, in 1953: ‘Once they got the claw on the tail and started to heave them up to the chute, he could’nae clear, they had to go cut some of da blubber off, it tilted the boat, you understand what I’m saying.’ Clark was on the smaller catcher boat for that whale, and remembers gunning top speed, shooting harpoons at the whale multiple times before being successful. ‘Now, I’ll never forget this,’ he says. ‘When I get down and looked, he’d dropped a killer harpoon, well this to me looking back on life, I’m not really thrilled on what we done.’

Many of the Shetlanders spoke about whaling as a deep and broad experience, an identity, a unique landscape, the allure of the whale itself. ‘There’s no doubt about that,’ says Jamieson. The close quarters of a whaling ship, albeit an entire factory floating in the middle of the sea, created a kind of seclusion that even the edge of Antarctica couldn’t bring. Shetland whalers who worked on catcher boats or factory ships lived between the antipodes, commuters to the edge of the world. They had an understanding of the ‘seasonal round’ – that is, the shift in natural-resource harvesting that each season brings. They knew that there was an end to the abundance of the sea.

‘I didnae think about it then because it was all money as far as we was concerned’

The last survivors of the whaling industry remember that the end always seemed to be near. Older hands had seen the days of huge catches – 100-ton blue whales hauled up in the back of factory ships, butchered onboard and gone in a day. Then, the catches grew skimpy. Numbers shrank too, and demand also ebbed. While the Second World War had prolonged need, in reality the demand for whale oil was in decline. From their first days aboard, many remember older whalers talking about the industry’s demise.

In 1963, the last floating European whale factory sold to firms in Japan. The end of the industry did not come from the appearance of an animal rights movement but rather the speed of harvest and inefficiencies of running a business between the Southern Ocean and the Shetlands. ‘To me, I didnae think about it then because it was all money as far as we was concerned,’ says Clark. By the end of the industry, catcher boats were competing with each other, racing against each other to shoot whales.

Leith Harbour’s whaling station manager Gerald Elliot saw otherwise. In his 1998 memoir, he writes: ‘We all realised we were near the end of our great whaling venture [by the 1950s].’ For Elliot, though, work for Salvesen would continue in Edinburgh as Salvesen changed their focus to ground transport and refrigerated trucks. As Britain’s whaling industry petered out, Shetlanders would pay a heavy toll.

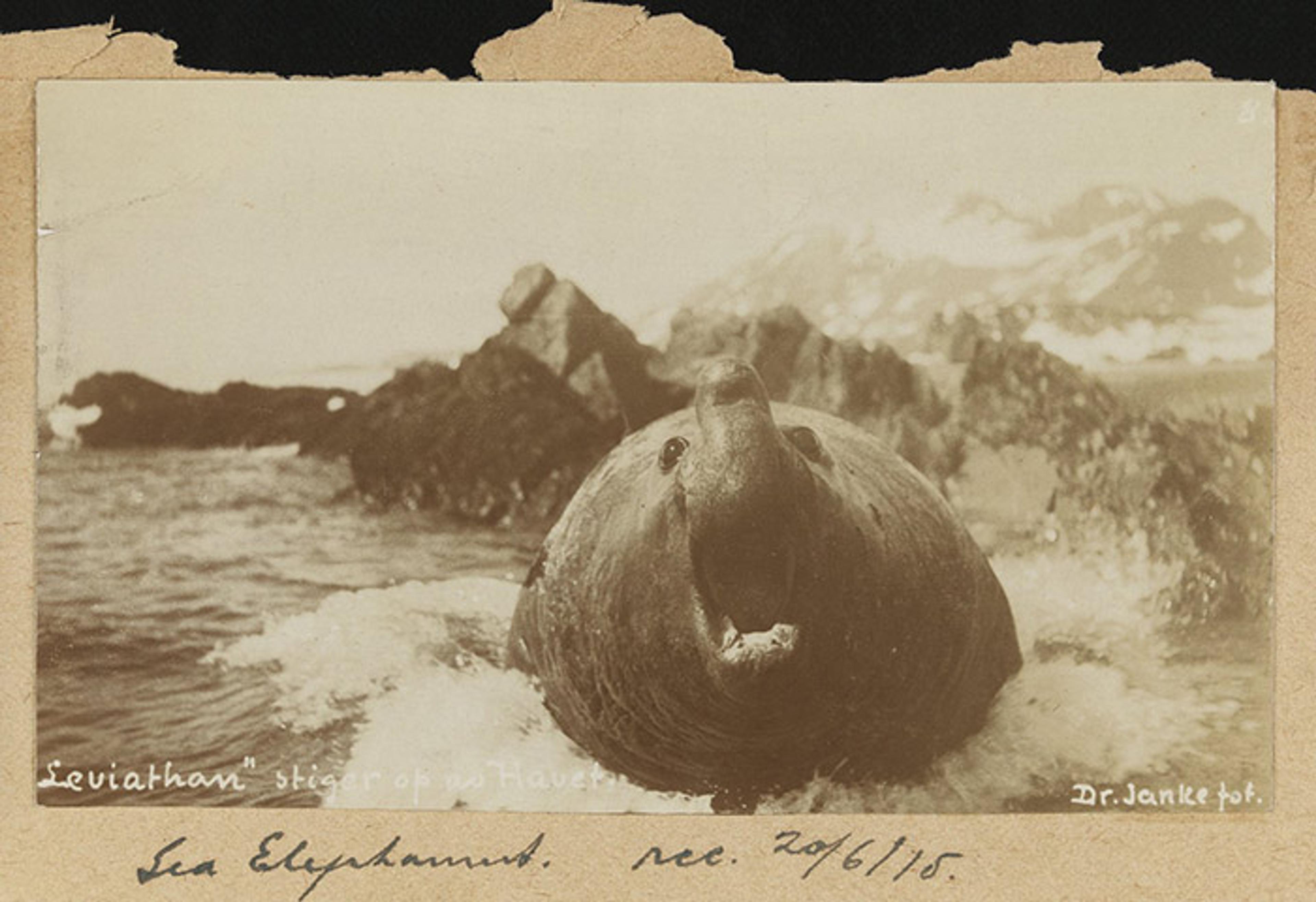

Resident of South Georgia, 1915

From apparent abundance to seemingly sudden scarcity, the Shetlanders’ relationship with the whale carried obvious significance. Salvesen set up a financial trust for Shetland men, knowing that the company had made fortunes on their backs. Men had spent their entire working lives on the ships owned by Salvesen, or at least servicing them. And yet there was no official warning of the end: upon arriving home from Antarctica, letters simply awaited the Shetland whalers telling them there would be no more whaling. Soon after, Salvesen contracted a lawyer in Shetland to distribute money allotted for now-unemployed whalers. The trust money was meant to facilitate more of the same type of work – buying fishing or lobster boats, for instance, or a tractor for croft land, or a few sheep to herd. They presumed the Shetland men would continue making a living from the sea.

In houses and cafés and cabins across the main island today, the last of Shetland’s whalers made clear that they never intended for their work to drive an animal nearly to extinction. Those men gather as part of the Salvesen Ex-Whalers Club, both on the mainland of Scotland and on Shetland itself, bonded through a job and isolation in ways similar to military men.

‘I can always remember, when I came back to Shetland I took the taxi through to Bigton in the mornin’ when de boat come in,’ says Willie Tait. ‘When it came in over de top of de hill dere and I looked out at St Ninian’s Isle and what dey call de Louse Head … I nearly crying.’

In July 2017, the Natural History Museum in London hung the skeleton of a blue whale from the rafters, above the grand Hintze Hall. At one time, a diplodocus named Dippy towered here, introducing visitors to the Earth’s grand ecological history. Now it is the whale, almost brought to extinction at the hands of man, peering down from above, her tail nearing the foot of Charles Darwin’s white statue. The whale’s name is Hope.