Hamoukar, Syria. 20 May 2010. We are midway through what will be the last excavation season at the site for some time. The following spring will see the outbreak of a long and brutal civil war. Today, though, the archaeologist Salam Al Kuntar, balanced on tiptoe at the bottom of a tomb, has just uncovered a little green stone. It is a cylinder seal, an ancient administrative device. We roll the tiny seal in clay – just as its former owner once would have – to reveal an impression of the intricate scene carved into its surface. It may not be the finest seal ever seen, but the tableau is eye-catching: a stick-figure man and woman are having sex, the man standing behind the woman, who bends over to drink from a jug on the ground. And is that a straw emerging from the mouth of the jug?

This is not the only erotic drinking scene that has survived from ancient Mesopotamia. And many of the others quite clearly feature a straw. Indeed, the drinkers of ancient Mesopotamia often drank via straw – though not always, shall we say, in this particular position. Hundreds of cylinder seals feature banquet scenes, and many show drinkers seated around a shared vessel, sipping beer through long straws. Banquets were a key part of the social calendar in Mesopotamia, and beer was an essential element. But people also drank beer at home, on the job, in the tavern, in the temple, pretty much everywhere.

Ancient clay plaque depicting an erotic drinking scene, 2000-1500 BCE, Tello (Girsu), Iraq. Courtesy the Louvre, Paris

Perhaps you have encountered the notion that beer was ‘invented’ in Mesopotamia. That is a hypothesis at best. Our knowledge about the early days of beer in Mesopotamia – about the prehistory of beer in the region – is scant. And, as the global search for earlier and earlier traces of alcoholic beverages gains steam, there is at least one key takeaway: beer was invented (or discovered) many times in many different places. Moreover, many of the earliest beverages were hybrids, drawing their fermentable sugars from a mix of fruits, grains, honey and other sources.

As I recount in my new book In the Land of Ninkasi, Mesopotamia was the world’s first great beer culture: an ancient society that was thoroughly steeped in beer, where beer was not a novelty but an everyday necessity and a fundamental cultural touchstone. The famous ‘land between the rivers’ was also the land of Ninkasi, goddess of beer. When Ninkasi poured out the finished beer, ready to drink – a Sumerian song tells us – it was like ‘the onrush of the Tigris and the Euphrates’.

It is in the centuries just before 3000 BCE, the late Uruk period, that the beer scene in ancient Mesopotamia begins to come into focus. Unheard-of numbers of people were living together in the world’s first cities. Inequality was on the rise. Decision-making power had been handed over to the world’s first states, the first centralised governing regimes (or, if you buy one recent theory, a more democratic system of councils and popular assemblies). In the midst of all this, somebody (or more likely, somebodies, plural) also pioneered the world’s first writing system and, along with it, the first bureaucracies and red tape. And what were those trailblazing bureaucrats writing about? Beer! The late Uruk period has given us both the earliest physical traces of beer in Mesopotamia, preserved as organic residues within ceramic vessels, and the first written evidence for beer in world history.

A cylinder seal impression depicting beer-drinking through straws, 2600-2350 BCE, Khafajeh, Iraq. Courtesy ISAC Museum/University of Chicago

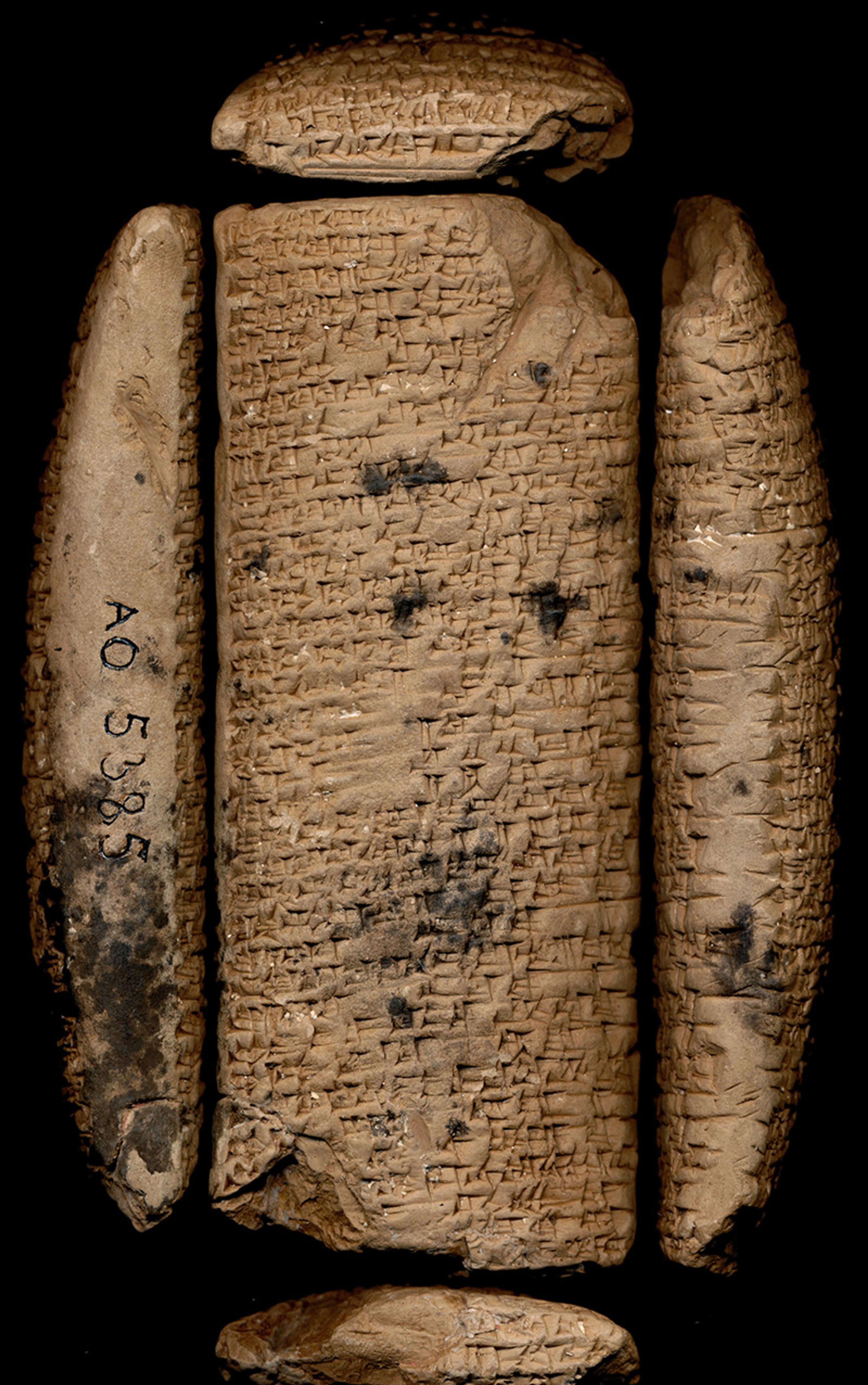

Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets, densely packed with cuneiform characters, testify to more than three millennia of history in Mesopotamia. And thousands of those tablets testify to more than three millennia of beer. They allow us to peer into the minds and mouths of our beer-drinking forebears – what kind of beverages they preferred, how these beverages were made, what they meant to people. Thanks to more than a century of archaeological excavation, we can also bring these documentary sources into conversation with other remains – architecture, ceramics, stone tools, cylinder seals, carbonised seeds – that allow us to look beyond what was put down in writing. We can, for example, take a virtual tour through the spaces where beer was brewed, reconstruct the brewer’s toolkit (and use replica vessels to brew some beer ourselves), or sneak a peek at exclusive elite banquets through the eyes of ancient artists.

Once the beer has done its work, the goddess’s ploy bears fruit

Given the time that separates us from them, it is a wonder that so much has survived. But there is one thing about studying people who lived thousands of years ago and spoke languages long-dead: one must get comfortable with uncertainty. I say that we face up to this issue head-on and try to achieve an honest assessment of what we know about beer in ancient Mesopotamia, how we know it and what we do not know for certain. To give you a sense of where things currently stand, I offer here a series of snapshots. Each begins with a brief vignette, a bit of historical fiction to set the scene.

First stop, the abzu, domain of the god Enki, deep down below the earth’s surface in the underground freshwaters. The aftermath of a drinking party. A beer-befuddled Enki – in most other situations, a wise trickster – has just regained his wits. Frantic, he turns to his minister Isimud: ‘Where am I? Where did she go? Where’s all my stuff?’ The panic rising, he begins to enumerate the missing items, all the so-called arts of civilisation, his most prized possessions. ‘Where are the noble sceptre, the staff and crook, the noble dress, shepherdship, kingship? Where are the craft of the carpenter, coppersmith, scribe, leatherworker, and builder? Where are wisdom, attentiveness, respect, awe, and reverent silence?’ The list goes on. In every case, the answer from Isimud remains the same: ‘You gave them to Inana.’

This (paraphrased) episode from a classic piece of Sumerian literature – the tale of Inana and Enki – establishes one point of connection between beers past and present. In ancient Mesopotamia, the beverage known as kaš in Sumerian and šikaru in Akkadian (pronounced ‘kash’ and ‘shi-ka-roo’) was not just liquid bread, a nutritious and filling foodstuff. It was a beverage that did things to people. In this case, the goddess Inana exploits the inebriating effects of beer. She dons her most beguiling outfit – topped off with a special crown – and gives the ensemble a once-over to make sure that it will have the desired effect. The gist of her appraisal: ‘My genitals are absolutely amazing!’ Satisfied, Inana heads off to visit Enki at home, where she plans to ‘speak coaxingly’ to him. He welcomes her, and they sit down together to drink. Once the beer has done its work, a competition ensues and Inana’s ploy bears fruit. A drunken Enki hands over many of his coveted powers, and Inana boards the Boat of Heaven to make a rapid getaway.

So drinking beer could lead to inebriation. That’s hardly an earth-shattering statement. But not all specialists agree about the alcohol content of Mesopotamian beer. Some think the beer would have been only mildly alcoholic. The logic here varies, but one could point to the fact that children were sometimes given beer, not just on the sly but direct from the hands of temple administrators. How do we know? Because they made sure to provide careful documentation. In one case, children like Andurre, Ebina, Ili-ešdar, Baran-kagal, Bilzum, Il-zima and Ergu-kaka each received 10 litres of beer per month. Can we assume that the beer in question was low in alcohol content? I’m sceptical. Sure, doling out beer (of any sort) to minors might be frowned upon today and might very well land one on the wrong side of the law. But world history offers up an abundance of counterexamples.

I’m even more sceptical about any suggestion that we can generalise further and assume that all beer in ancient Mesopotamia was low in alcohol content. Why, for example, would the drinkers who populate Mesopotamian literature – drinkers like Enkidu, soul mate of Gilgamesh, who guzzles seven goblets and begins to sing – experience effects consistent with a higher level of alcohol consumption, such as feelings of freedom, elation, lightness, energy, satisfaction, wellbeing, conviviality? And why, in the written record, would drinking be associated with impaired judgment, interpersonal friction and (perhaps, in one case) impotence? It’s clear that at least some of their beer was plenty potent. In the Mesopotamian worldview, beer was not just a generic foodstuff. It was a beverage that did things to those who drank it, that could impact them physically, mentally, emotionally. We cannot accurately assess the role of beer in ancient Mesopotamia without acknowledging its inebriating potential.

The Mesopotamian tavern was a commercial space where one could purchase beer, food and possibly sex

The year is 650 BCE. Ashurbanipal is king. We are in the city of Nineveh, capital of the Neo-Assyrian empire, at a small tavern near the river. We have managed to stake out a spot at a corner table, ideal for people-watching. We raise our mugs of beer (or could it be date wine?) for a taste but then freeze. All eyes have suddenly shifted to the front door, left open to catch any hint of a breeze. What are those two guys outside up to? One has just dipped his fingers into a small jug and then smeared something across the doorframe. They both enter and head straight for the stairway that leads to the roof. A few minutes later, we hear some muffled chanting and then clear and firm (in Akkadian, not English): ‘Ishtar, Nanay, Gazbaya help me in this matter!’ When the chanting picks up again, we turn back to our beers but cannot help a few more furtive glances back at the stairway. What is happening?

If we could have followed those two men en route to the tavern, we would probably be even more confused. They had taken a winding route through the city, one of them stopping periodically to collect dirt from the ground and place it in a pouch on his belt. Their last stop was the river, where they had collected water in a jug and mixed in the contents of the pouch and a few dribbles of oil. It is that mixture that ended up smeared onto the doorframe of the tavern. This whole strange trip across the city of Nineveh was part of an elaborate ritual procedure. The cuneiform tablet that spells it out stipulates the collection of 18 different kinds of dust: dust from a god’s house, from a city gate, from a sandstorm, from the door of a tailor, a maltster, an innkeeper, a gardener, a carpenter, and many more. And all that dust-gathering was just one among the many steps in this ritual – all for the sake of guaranteeing profit for the tavern.

A Sumerian beer cup, 2700-2600 BCE. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

This was a namburbi ritual, an effort to counteract the effects of a negative omen. The Mesopotamian world was full of signs, messages from the gods imprinted in the flight of birds, the bark of a dog, the folds of a sheep’s entrails. Ritual specialists could read these signs – for example, signs predicting financial ruin for a tavern – and recommend preemptive measures. In Mesopotamia, the tavern was a commercial space, a privately owned business where one could purchase beer and food (and possibly sex, if one desired). By the Neo-Assyrian period, one could also purchase date wine at many taverns. Confusingly, this newly popular beverage was also called šikaru or ‘beer’ in Akkadian. Taverns were often run by female tavern-keepers, most famously Shiduri, a wise tavern-keeper at the edge of the world in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Taverns were places of celebration, inebriation, fornication and sometimes criminal collaboration. The Code of Hammurabi demands that a tavern-keeper report and arrest any criminals gathered in her establishment. Taverns also had a special ritual potency. Certain remedies, for example, required the patient to visit a tavern and touch the brewing vessel or its wooden stand.

Kushim pulls the wooden door tight and heads off down the street, surprisingly busy for this hour of the day. A friend peeks out from a doorway and tries to stop him for a chat, but there is no time. Kushim rushes on with a quick wave, catching a glimpse of the slow-moving Euphrates River between buildings on the right. Up ahead, a white temple glitters in the early morning sun, high above the city of Uruk. Kushim turns his attention to the colourful structures that cluster atop another height to the right. He is headed in that direction, on his way to work. When he reaches the brewery, Kushim heads straight to a side room, off the main courtyard, and breaks the mud seal locking the door. Grabbing two small clay tablets from a shelf inside, he scans down the columns of figures and breathes a sigh of relief. No need to worry. Everything checks out. The supplies of malted barley delivered last week match up perfectly with the batches of beer that he sent out yesterday.

These tablets are some of the earliest written documents in world history, dating to about 3000 BCE. We may not know exactly where they were produced or who this ‘Kushim’ was. But we do know that someone was carefully recording deliveries of beer and the ingredients used to produce particular types of beer. Quite a few of the so-called archaic texts revolve around the production and distribution of beer. And beer remained a matter of official, administrative concern over the ensuing three millennia of Mesopotamian history.

The room is nearly silent, except for a gurgling: ‘dubul dabal, dubul dabal’ – the sound of beer brewing

Beer appears on thousands of cuneiform tablets. We learn, for example, about different types of beer. At one point: golden, dark, sweet dark, reddish brown, and strained beer. Not long after: ordinary, good, and very good – or possibly ordinary, strong, and very strong beer. Then a bit later, some beers of less certain translation: maybe sweet, red, date-sweetened, and bittersweet varieties. Often the two key brewing ingredients were malted barley, like many of our beers today, and the enigmatic bappir – possibly a dry, crumbly fermentation starter. Some beers also featured unmalted barley, emmer wheat, date syrup and/or aromatics. Exactly which aromatics is up for debate, but hops, so crucial today, were not in the mix.

Beer was brewed at home, in neighbourhood taverns, and in breweries managed by palace and temple authorities. In some cases, we know the names of the brewers – for example, homebrewers Tarām-Kūbi and Lamassī (both women), tavern-keepers Magurre and Ishunnatu (both women), and palace brewers Qišti-Marduk and Ḫuzālu (both men). Others remain anonymous but left traces of their brewing activities in the archaeological record: for example, in a temple brewery excavated at the site of modern-day Tell al-Hiba, Iraq, in what was the ancient city of Lagash.

We are walking down a narrow alleyway, mudbrick walls rising to either side. On the right, we pass an inconspicuous doorway, a side entrance that leads into the Bagara, the main temple of Ningirsu, patron god of the city of Lagash. A wisp of smoke escapes from another doorway to the left. We ease open the wooden door and are hit with a blast of malty aroma. Avoiding the smoke that pours out of a room to the right, we step into another room on the left, pulling the door shut behind us. The room is dimly lit and nearly silent, except for a faint gurgling: ‘dubul dabal, dubul dabal, dubul dabal.’

That is the sound of beer – at least according to one piece of Sumerian literature. It is the sound of two brewing vessels speaking with one another. The one with a hole in its base sits above the other, and they make a ‘dubul dabal’ sound, Sumerian onomatopoeia for the sound of a liquid dripping from the upper to the lower. These two brewing vessels, well attested in the written record, were not actually uncovered by archaeologists within the room that we visited in the building next to the Bagara temple at Lagash. But we have good reason to suspect that this building was a brewery. What is more difficult is pinning down exactly what took place in each room, exactly how beer was brewed.

The most detailed account of the brewing process appears in the ‘Hymn to Ninkasi’, goddess of beer. But this lyric portrait of Ninkasi at work in the brewery is hardly a set of instructions for brewing beer. It is preserved only on three known tablets, in each case followed immediately by another song, perhaps a sort of drinking song written to celebrate the opening of a new tavern. What makes the hymn so useful for students of Mesopotamian beer is that it seems to depict Ninkasi brewing up a batch of beer, step by step, from start to finish. But how much weight should we really place on this one song? Is it really a useful guide to exactly how beer was actually brewed in Mesopotamia? Imagine that you are an archaeologist of the future. You are trying to recreate the beers of the mid-20th century CE, and all you have to go on are these lines from a contemporary drinking song known as ‘Beer, Beer, Beer’: ‘A barrel of malt, a bushel of hops, you stir it around with a stick…’ The ‘Hymn to Ninkasi’ has more to offer than that, but it is still more song – maybe even legit drinking song – than recipe.

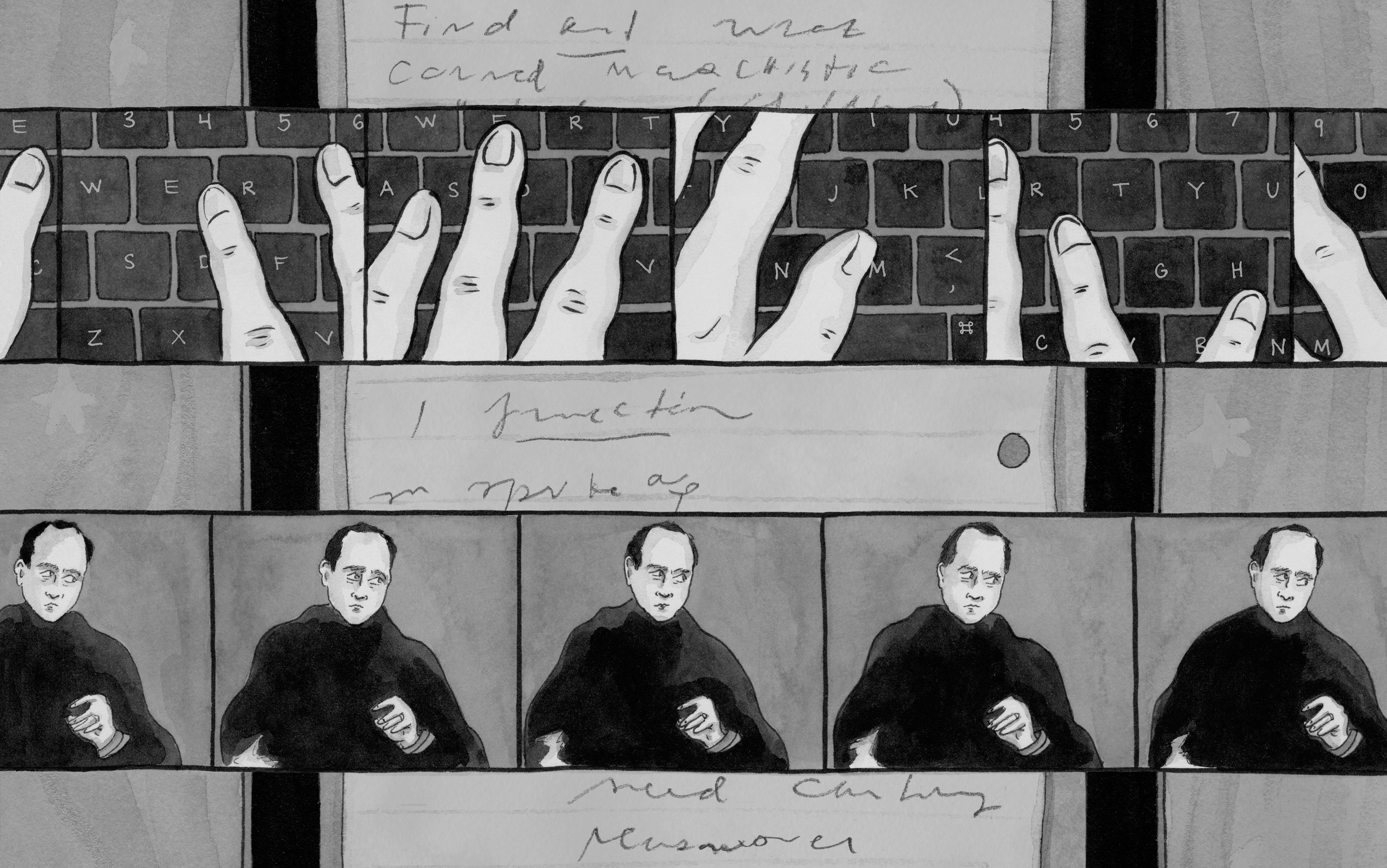

Cuneiform tablet recounting the ‘Hymn to Ninkasi’. CDLI/Louvre Musuem, Paris

So, what exactly does this song from the distant past offer us? In one sense, it offers the possibility of establishing a direct channel of communication between brewers past and present, of establishing a sense of shared tradition across a span of nearly 4,000 years. But there is also a persistent danger of inadvertently flattening the past into the present, of missing some of what made their world different from our own. Ultimately, it’s all about translation. What exactly is Ninkasi up to – if we follow the classic but now dated translation by Miguel Civil – when she mixes the bappir (a key brewing ingredient) with sweet aromatics and bakes it in a big oven, when she waters the malt and then soaks it in a jar, when she spreads out the cooked mash on reed mats, when she holds the sweetwort in her hands? Can we assume that she’s basically just doing some version of what brewers still do today, if in a less scientific or less sophisticated fashion?

I think not. More specifically, I think we need to be careful to avoid two seductive ‘traps’ that have hindered interpretation of this challenging Sumerian text. The terminological trap tempts us to translate the text using terminology drawn from the European brewing tradition. I suspect a square-pegs-round-holes situation, a modern brewing lexicon that does not match up well with past reality. The minimalist trap, on the other hand, entices us into assuming that ancient brewers relied on a simple, straightforward set of steps: just the basics. To the contrary, since the Mesopotamian brewing tradition probably stretched back deep into the prehistoric past, we should expect sophistication, creativity, complexity and diversity.

The beers provided our audiences with a unique sort of visceral, embodied connection to the ancient past

14 August 2013, 5:55pm. Pat Conway, co-owner of Great Lakes Brewing Company, and I are huddled in an office off the main dining room at his Cleveland brewpub. The first tasting event for our Sumerian Beer Project kicks off in five minutes. But we have just realised – we forgot to name the beers. After some quick brainstorming, we settle on a tribute to the famous adventuring duo, Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Fast-forward 45 minutes. Pat has waxed lyrical about our collaborative brewing effort. I have given a lecture about ancient Mesopotamia. The brewers have explained our brewing process. The guests have had a taste of our two beers, Gilgamash and Enkibru, served up in tasting glasses. But now the moment of truth. A large ceramic vessel waits at the front of the room, straws emerging from its mouth. Will anyone be willing to try sipping some Enkibru Sumerian-style? We had our doubts, but the audience did not. The answer was a resounding ‘Yes!’

Photo supplied by the author

This event set the pattern for others to follow. We served our guests two beers. Enkibru was brewed using authentic ingredients, equipment and brewing methods. It was tart, uncarbonated, milky-looking and intriguingly herbal. Gilgamash, brewed using the same ingredients but modern equipment and a commercial yeast, was more familiar, something like a Belgian saison. These beers were the result of a multi-year collaboration between Great Lakes Brewing Co and the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (at the time, the Oriental Institute) at the University of Chicago. I signed on as a graduate student and never looked back. This was my entry point into the world of Mesopotamian beer.

Did we manage to produce an exact replica of any beers from the distant past? Definitely not. We had to rely heavily on educated guesswork. But we did provide our audiences with a unique sort of visceral, embodied connection to the ancient past. If you would like to have a taste of Gilgamash too, my book includes a brew-it-yourself recipe to try at home. If you give it a go, I suggest a ceramic jug and some long straws. And with the first sip – or any time you find yourself in need of a toast – I propose that you borrow a line from our ancient Mesopotamian drinking song and call on Ninkasi, goddess of beer. ‘May Ninkasi live together with you!’ Or give it a try in Sumerian: ‘Ninkasi zada ḫumu’udanti!’