In April 1955, at a closed session of the Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, India’s prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru spoke forcefully about the need for countries in Asia and Africa to refuse to join either of the two great powers – the United States and the Soviet Union – and to remain unaligned. Arguing that alignment with either power during the Cold War would degrade or humiliate those countries that had ‘come out of bondage into freedom’, Nehru maintained that the moral force of postcolonial nations should serve as a counter to the military force of the great powers. At one point, Nehru chided the Iraqi and Turkish delegates at the conference who had simultaneously spoken favourably about the Western bloc and the formation of NATO while lamenting the continued French colonisation of North Africa. Nehru said:

We must take a complete view of the situation and not be contradictory ourselves when we talk about colonialism, when we say ‘colonialism must go’, and in the same voice say that we support every policy or some policies that confirm colonialism. It is an extraordinary attitude to take up.

A few years later, in 1961, along with Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, Sukarno of Indonesia, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Nehru became one of the founders of the non-aligned movement. Having lifted the yoke of British colonialism, India presented itself as poised to take on the moral and political leadership of the decolonising world. This was perhaps to be expected, especially given that India was the largest and most populous country to become independent from European colonial rule. The story of India’s anticolonial struggle, too, had been mythologised by the nonviolent resistance offered by Indian figures such as Mahatma (‘great soul’) Gandhi. Nehru, too, was perceived as a charismatic and well-read leader who spoke for the people of Asia and Africa, and attempted to find what the scholar Ian Hall has called a ‘different way to conduct international relations’. The stature of both men played a critical role in establishing Indian dominance in the Third World order, and also in establishing ‘the idea of India’ as a secular liberal democracy that was built on the foundational idea of unity in diversity.

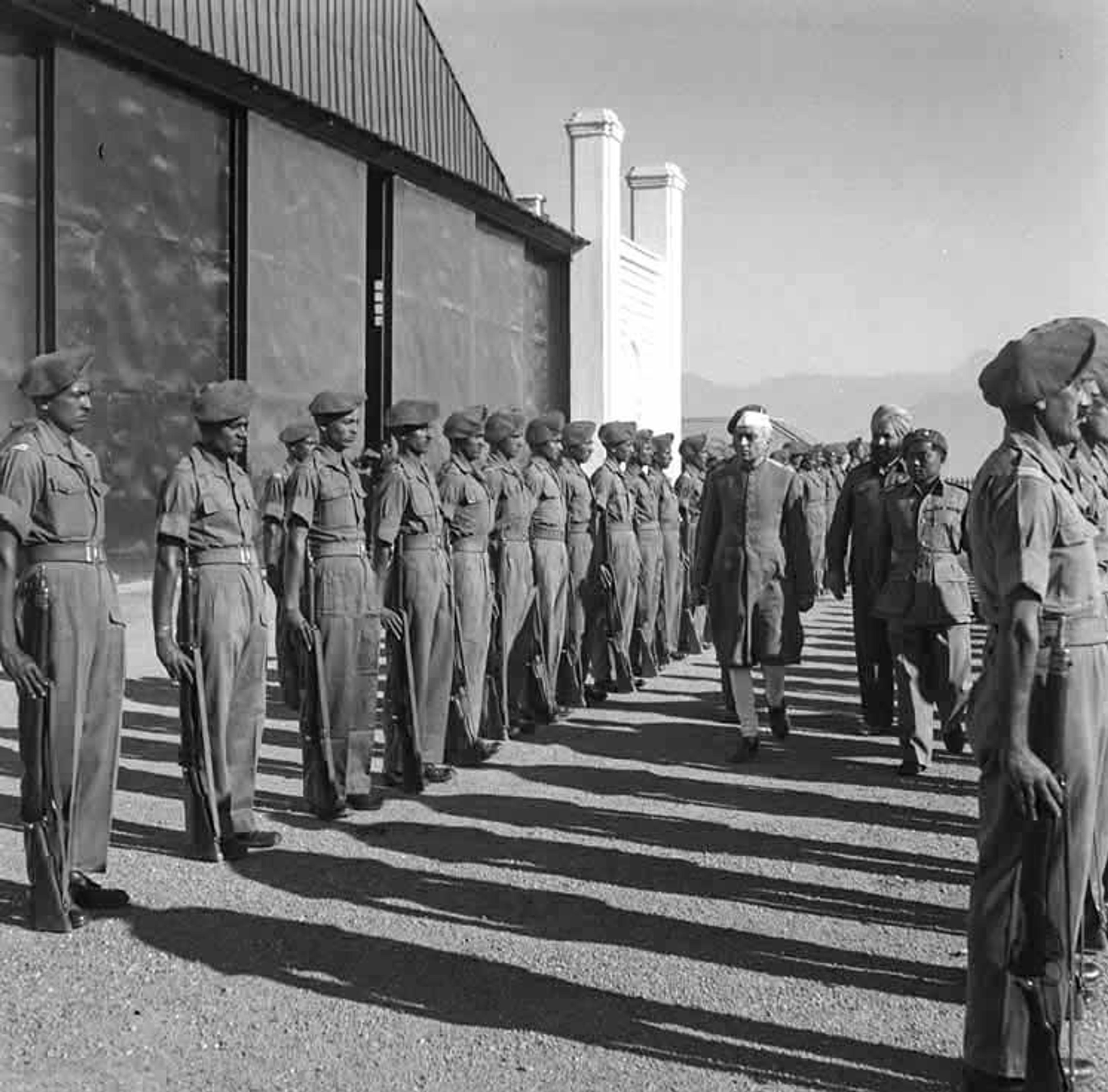

Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru inspecting a guard of honour, in Srinagar during his visit to the city in November 1947. Courtesy Publicresourceorg/Flickr

Even as Nehru proclaimed the moral superiority of India for taking a stance against colonialism in all forms, he oversaw India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir. In Kashmir, Nehru said, ‘democracy and morality can wait’.

In the middle of the 20th century, a wave of anticolonial and national liberation movements gained independence from European powers, by exercising their right to self-determination. Nationalist leaders of the former colonies, however, remained committed to the ideals of the nation-state and its territorial sovereignty that derived from European modernity. Independence, it was widely accepted, came in the form of the nation-state, which outshone other forms of political organisation or possibilities. The borders of the nation-state became contested, as European powers often imposed boundaries that ill suited visions of what constituted the political community. This would have deleterious consequences for places where geography, demographics, history or political aspirations posed serious challenges to nationality. In turn, newly formed nation-states asserted their newfound sovereignty through violence and coercion, which had implications for Indigenous and stateless peoples within their borders whose parallel movements for self-determination were depicted as illegitimate to the sovereign nation-state order. Mona Bhan and Haley Duschinski call this process ‘Third World imperialism’.

Some anticolonial nationalists were real nationalists, that is, they saw claims of self-determination within their imagined community of a nation as ‘separatist’, ‘secessionist’, ‘ethnonationalist insurgencies’ or ‘terrorism’. Such framings, rife in Indian discourses on Kashmir, are ahistorical and dehumanising. When we move beyond seeing these regions from the perspective of the dominant nation-state, we come to see how they are places with their own histories, imaginaries and political aspirations – some of which may reinscribe the nation, while others seek to move beyond it through understandings of other forms of sovereignty.

In popular and even scholarly discourses, colonialism is often seen as happening ‘overseas’ – from Europe to somewhere in the Global South. Many people see colonialism as something that we are past temporally, despite acknowledgement of its ongoing legacies. Forms of colonialism within the Global South remain more difficult for many to see because many of these regions are geographically contiguous to one another and, thus, seen as having some form of cultural or racial unity that would form a nation. This results in what Goldie Osuri calls a ‘structural concealment of the relationship between postcolonial nation-states and their [own colonies],’ as well as the concealment of ‘the manner in which postcolonial nationalism is also an expansionist project.’ Contemporary colonies – like Kashmir, Western Sahara, Puerto Rico, Palestine, East Turkestan, among others – show the porous boundary between colonialism and postcolonialism, raising some difficult questions about the current global order.

The Himalayan region of Kashmir, at the northernmost tip of the subcontinent, is surrounded by India, Pakistan, China and Afghanistan. Kashmir had long been a separate kingdom, at the confluence of Persian and Indic spheres – hard to simply mark into the Persianate or the Indic (themselves, as Mana Kia points out, somewhat amorphous descriptions). Starting in the 16th century, Kashmir came to be ruled as a province by the Mughal, Afghan, and Sikh empires. When the British ruled the subcontinent, they sold Kashmir to the Dogras, Hindu chiefs from the nearby region of Jammu, in the aftermath of the first Anglo-Sikh War in 1846. Under the Dogras, the newly constituted Jammu and Kashmir was one of the larger princely states within the broader ambit of British colonial rule. Its strategic significance in the north of the subcontinent was important for the British, especially during political competition with Russia for influence in Central Asia, known as the Great Game.

Unlike most princely states, Jammu and Kashmir was one of the few where the religious identity of its ruler was different from those of the majority of its subjects. The Dogras were Hindu, while more than three-quarters of the people in the state were Muslim. This perhaps would not have been so significant had the Dogras not effectively run what the historian Mridu Rai has called ‘a Hindu state’, whereby the rulers privileged the Hindu minority and excluded ‘Muslims in the contest for the symbolic, political and economic resources of the state’. Kashmiri Muslims faced immense repression. Most of them were peasants or artisans, forced to pay high taxes to the Dogra authorities. While an anticolonial movement against the British spread across British India, in Jammu and Kashmir, an anti-Dogra freedom movement gained traction in the 1930s and ’40s, only to be sidelined by the sweeping events across the subcontinent.

Hari Singh, the last Dogra ruler of Jammu and Kashmir, pictured in 1931. Courtesy Wikipedia

During the Partition of 1947, the territories that the British directly (British India) or indirectly (princely states) governed in the subcontinent became the two new nation-states of India and Pakistan. Independence, and partition, ended nearly two centuries of British colonial rule. Partition was far from inevitable. Leaders of the Muslim League, such as Muhammad Iqbal and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, discussed a large federation with largely self-governing autonomous provinces to address the concerns of communities, especially Muslims of the subcontinent, who feared Hindu domination in a democratic India. In 1947, when the British hastily drew the lines that established India and Pakistan, nearly 1 million people were killed and another 15 million displaced in the ensuing violence. However, the consolidation of India’s other territorial boundaries was not without incident. Junagadh, a princely state in what is today Gujarat, which had a Muslim ruler but a majority Hindu population, was annexed in February 1948; here, a plebiscite was held and an overwhelming majority voted for India. In September 1948, Nehru violently annexed the princely state of Hyderabad during what was called Operation Polo. Nehru crushed movements for self-determination in Northeastern India, in Nagaland and Manipur.

While Nehru viewed the UN as promoting world peace, he resisted a number of UN resolutions

In mid-1947, in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, Hari Singh, the last Dogra ruler, brutally crushed a local Muslim anti-Dogra rebellion. The rebels wanted Jammu and Kashmir to join Pakistan and were afraid that the Hindu ruler would opt for India. The height of the violence became known as the Jammu Massacre and lasted from October to November 1947. The Dogras, supported by Right-wing forces in India, including the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or the ‘National Volunteer Organisation’) ethnically cleansed Muslims from Jammu, changing the demographics of the region from a Muslim to a Hindu majority in a matter of weeks. After Pathan Muslims from northwest Pakistan joined their coreligionists in the rebellion against the Dogras and were threatening to take over Kashmir, Singh signed a contested Treaty of Accession with the Indian government. By the terms of the treaty, India sent its army into Kashmir in late October 1947. India and Pakistan subsequently went to war and, in January 1948, India took the Kashmir issue to the United Nations. The UN called for a plebiscite or referendum to be held in the region once hostilities ceased (with the options being India or Pakistan). In 1949, the UN brokered a ceasefire line, later renamed the Line of Control, that divided the region between the two countries.

At first, Nehru agreed to the plebiscite, confident that the people of the region would vote for India. Yet, as it became clear that a plebiscite would not go in India’s favour, his commitment to it waned. While he ostensibly viewed the UN as an important international body tasked with promoting world peace, Nehru resisted a number of UN resolutions. He declared that Pakistan had joined military alliances with the US which made the plebiscite moot. India used other justifications for its opposition to a referendum, asserting that Pakistan had not removed its army from Kashmir, which the UN had called for, and arguing that local elections to the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly served in lieu of the plebiscite and proved that Kashmiris had opted for India. Nehru maintained that these local elections made a plebiscite redundant. In fact, UN resolutions had called for both countries to remove their troops, but there was no agreement about the manner of troop removal, or their number, nor about the entity that would oversee the plebiscite.

In 1951, the US also stated that local elections in Kashmir were not a substitute for a plebiscite. Within the part of Kashmir that it controlled, the Indian government put client regimes in power that were in support of accession to India, promising them greater autonomy within the Indian union. This autonomy was enshrined in Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which gave the Jammu and Kashmir state ‘special status’ within the Indian Union. It ‘allowed’ the state its own constitution, flag and legislative assembly; in addition, the head of the state was called a prime minister, unlike Indian states where the head was a chief minister. India was supposed to be responsible for defence, foreign affairs and communication. While India argued that Kashmir’s client regimes and local political leaders were ‘democratically elected’, this was not the case. The first election in 1951 for the local assembly was rigged as the pro-accession National Conference ran unopposed in 73 out of 75 seats. Those who opposed Kashmir’s accession to India were not allowed to run. Pakistan resisting its troop removal from Kashmir was also based on the argument that a plebiscite could not take place under a local government that was effectively put in power by the Indian state as that would influence the outcome.

Within a few years, India moved beyond the restricted mandate of Article 370, and started to intervene in Kashmir’s internal affairs. Kashmir’s first prime minister and client politician, Sheikh Abdullah, offered some resistance. A 1953 coup replaced him with his deputy, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad. The Indian government would replace him with the next prime minister, G M Sadiq. Meanwhile, Kashmiri resistance to Indian rule grew, as Kashmiris demanded the plebiscite recommended by the UN and agreed upon by India and Pakistan. In the 1960s, some organised political mobilisations began to speak of a third option – complete independence from both India and Pakistan. Eventually, in the late 1980s, a rigged election and the impact of international developments – including the first Intifada in Palestine and the Afghan defeat of the Soviet Union – sparked an armed rebellion against Indian rule, supported by Pakistan. India militarised Kashmir at this time, making it the most militarised region in the world. The 1990s were a harrowing period in Kashmir, with daily news of killings, massacres, enforced disappearances, sexual violence, torture, crackdowns and arrests. Protected by draconian laws like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, the Indian army had (and still has) impunity in its control and governing of Kashmir. As Amnesty International reported in 1995, and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights confirmed in 2018 and 2019, there is a ‘consistent pattern of gross violations of human rights in Jammu and Kashmir’.

Kashmir is India’s colony. The exercise and expansion of Indian territorial sovereignty, especially in Kashmir, is a colonial exercise. The exercise of Indian power in Kashmir is coercive, lacks a democratic basis, denies a people self-determination, and is buttressed by an intermediary class of local elites or compradors. But it is also colonial because India’s rule in Kashmir relies on logics of more ‘classical’ forms of colonialism from Europe to the Global South: civilisational discourses, saviourism, mythologies, economic extraction and racialisation. As with all imperial or colonial forces, India has sought to rule over Kashmir through subjugating its people and trampling their rights.

Kashmir’s history is far more vibrant than that conceived of by exclusionary Indian nationalist history

India’s status as a leader of a global anticolonial order has made it difficult for the world to see Kashmiris as colonised. It has obscured the anticolonial struggle of Kashmiris against India. So, there has not been much support for Kashmir’s anticolonial struggle among various solidarity and anticolonial movements around the world. For decades, India insisted that the ‘Kashmir conflict’ was a territorial dispute to be solved between India and Pakistan; in recent years, it has denied that there even is a dispute or conflict in Kashmir. India instead maintains that Pakistan is interfering in India’s ‘internal affairs’. This claim completely erases the agency of Kashmiris who have been demanding their right to self-determination for more than seven decades.

Today, from Indian leaders on international forums to the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) IT Cell accounts on social media, you will hear that Kashmir is ‘an integral part of India’. The repetition is often supplemented by narratives of a 5,000-year-old Indian civilisation featuring a prominent role for Kashmir or claims that Kashmir simply belongs to Hindus. In reality, Kashmir’s history is far more vibrant than that conceived of by exclusionary Indian nationalist history; Kashmir defies easy civilisational binaries. Through the Silk Road, Kashmir was a pivotal part of East and Central Asia. Kashmiri traders and travellers journeyed from Srinagar to Samarkand, Bukhara, Kashgar and Tibet. Just as Kashmir was home to vibrant Sanskrit literature like the Rajatarangini, it was also home to Persian literature, like the Waqiat-i-Kashmir and the Baharistan-i-Shahi. Kashmir does not exclusively belong to any community – it has been home to Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims (including Sunnis and Shias) and Sikhs.

Many Indian scholars, too, replicate the notion that Kashmir is ‘integral’ to India. Viewing Kashmir’s history only from the prism of Indian nationalist frameworks, scholars like Sumit Ganguly and Sumantra Bose are unable to move beyond the need to situate Kashmir firmly within the Indian nation-state. Even the postcolonial scholar Partha Chatterjee, who, while critical of nationalism and a founder of the field of subaltern studies, conceptualises Kashmir entirely within an Indian constitutional or national framework. Mainly focusing on the events surrounding 1947 in Kashmir, as well as the decades after the armed rebellion of the 1980s, an earlier generation of Indian scholars tried to find answers to the ‘failures’ of Indian democracy to better accommodate Kashmir within its federal structure, refusing to acknowledge the denial of self-determination and imposition of a colonial occupation. More recently, the field of Critical Kashmir Studies has emerged to contest these statist framings, placing the study of Kashmir more firmly into anticolonial and anti-occupation epistemologies. Scholars of Critical Kashmir Studies examine how colonialism, settler-colonialism and occupation are all important aspects of India’s relationship with Kashmir, elements of which India has used to fortify its rule in Kashmir over time, and to manage Kashmiri resistance.

In truth, Kashmir was made integral to India in the aftermath of Partition. Through Kashmir’s client regimes, as well as the type of state-building that occurred under those regimes, India was able to further legally, economically and politically integrate Kashmir into the Indian Union. In my book Colonizing Kashmir (2023), I examine the decade that Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, the second prime minister of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, was in power, from 1953-63. As a client politician, he was tasked with confirming the state’s contested accession to India, but also with ensuring that Kashmiris realised that being under Indian rule would benefit them. The Indian government and Kashmir’s client regimes initially supposed that, if Kashmiris were to see the benefits of Indian rule, alternative political aspirations, such as independence or merging with Pakistan, could be kept at bay. As Nehru is reported to have told his predecessor, Sheikh Abdullah: ‘India would bind Kashmir in golden chains.’

I argue that Bakshi did this by utilising the politics of life, in which the Indian government and Kashmir’s client regimes propagated development, empowerment and progress to secure the wellbeing of Kashmir’s population and to normalise the occupation for multiple audiences. In an attempt to secure the livelihoods of Kashmiris, the politics of life entailed foregrounding the day-to-day concerns of employment, food, education and provision of basic services. At the same time, demands for self-determination were heavily repressed. Policies focused on land reform, building schools and increasing employment opportunities.

Bakshi was acutely invested in financially integrating Kashmir to India. He differed from Abdullah in seeing financial integration as important to development. Between 1953-1954, Bakshi renegotiated Kashmir’s financial relationship with the Indian government, placing certain fiscal demands on the Indian state with regards to grants and agricultural subsidies. The new arrangement also undermined Kashmir’s autonomy, ensuring that it would not be self-sufficient. In this way, Kashmir grew dependent on the Indian state, which gave the Indian government great leverage. Bakshi’s example is important to understand that colonial occupations are not a one-way process. They require native enablers, local collaborators who have agency in determining its contours.

Cultivation of Kashmir’s links with Hinduism was important to the early Indian colonial project

In the 1950s and ’60s, India also turned to film and tourism in order to further India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir, especially for Indian audiences. Dozens of Indian films, including most of the leading blockbusters like Kashmir Ki Kali (1964) or Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965), were made in Kashmir during this time, and middle- and upper-class Indian tourists flocked to Kashmir throughout the year for fun and adventure. Through their personal or cinematic experiences of Kashmir’s beautiful landscape – its rivers, lakes, forests and mountains – Kashmir became what Ananya Jahanara Kabir calls a ‘territory of desire’ for the Indian imaginary, consolidating colonial claims.

Kashmir was also a place of religious attachment for Indian Hindus, and cultivation of Kashmir’s links with Hinduism was important to the early Indian colonial project. Nehru and other Indian leaders would say that India’s secular ideals (as opposed to Pakistan’s religious ones) were proven superior through its only Muslim-majority state ‘choosing’ India. Despite exploiting Kashmir’s ‘secular credentials’ for international audiences, for domestic ones, India largely presented Kashmir as a Hindu place and the heart of Indian civilisation from ancient to present times. Muslim monuments, mosques, figures and histories were erased or toned down in tourism materials for Indian travellers. In the dozens of Indian films made in Kashmir during this time, it was rare to find a Muslim character, astounding given its Muslim-majority status.

Through educational institutions, school curricula and cultural reform, the Indian government and Kashmir’s client regimes have attempted to produce certain kinds of Kashmiris, in particular, good Kashmiri secular subjects. Yet, as a part of this secularism, historical and literary works have foregrounded Hindu geographies, imaginaries and histories, relying on British colonial and Brahmanical understandings of Kashmir’s history. For example, the ‘origin’ story of Kashmir (basically, how the region came to be) used in history curricula and tourism manuals relied on mythological Sanskrit texts like the Rajatarangini. It portrayed Hindus as indigenous or aboriginal to Kashmir, and Kashmir being a place of ancient Hindu learning. Muslims were depicted as ‘invaders’. Accounts of Kashmir’s past rely on Sanskrit texts (and also conflate mythology with history) while erasing other works in Persian that offer different narratives of history and belonging by drawing upon Kashmir’s significance for the Islamic world. In short, Indian nationalist history has relied on Orientalist and Brahmanical renderings of history to help enable anti-Muslim history. This has then furthered the idea that Kashmir is ‘integral’ to India.

Bakshi’s decade in power consolidated India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir, but it still did not result in emotionally integrating Kashmiris to the Indian union. The year 1963, when Bakshi was ousted from power, saw the flourishing of large movements for self-determination in Kashmir. After the Indian government massively rigged a local election in 1987, Kashmiris took up armed resistance. The Indian state resorted to killings, torture and disappearances. This does not mean that the decades prior were peaceful – state repression was high – but that various strategies were foregrounded in different moments, especially in response to Kashmiri resistance and international developments.

In August 2019, India revoked Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status, fully annexing the region, and advancing its settler-colonial ambitions. The government revoked laws that had previously restricted land, property and employment rights to Kashmir’s permanent residents. These restrictions had been insisted upon by Kashmir’s earlier client regimes to protect the demographics of the Muslim-majority state. Jammu and Kashmir’s Muslims now fear demographic change and an accelerated settler-colonial agenda by which Indian (Hindus) can now buy land and property and settle in the region, undermining the movement for self-determination. Indian officials are already on the record calling for ‘Israeli-like’ settlements to be built in Kashmir for Hindus. The Modi government’s removal of Article 370 was based on a long-standing demand by Hindu nationalists who felt unhappy that the Indian state under the Indian National Congress was trying to appease Kashmir’s Muslims with promises of autonomy. This decision was immensely popular in India.

Today, India is again using the politics of life, or the idea that it is benefiting Kashmiris through development and better opportunity to justify the abrogation, while also using film and tourism to declare normalcy. In the current phase of Indian control, the Indian state has completely undermined civil society. All possible modes of dissent – from pro-freedom groups to journalism, academia and human rights organisations – have been clinically silenced. From internet shutdowns, to the arrests of journalists or human rights defenders, to the surveilling of social media sites and restricting movement by suspending passports, India has left no stone unturned to criminalise political speech and project normalcy to domestic or international audiences. A new description of ‘white-collar terrorist’ is given to anyone who contests Indian sovereignty, and anti-terror legislation is used against all forms of expression, including for example, against students cheering for the Pakistani cricket team, as happened last year. Because Kashmiri Muslims fear losing their livelihoods or property, many have been forced to resort to self-censorship.

The United Arab Emirates and Israel have signed agreements with the Indian government, ensuring foreign investment for Kashmir. India has long exploited Kashmir’s natural resources, including water. During the cold winter months, Kashmiris face electricity scarcity and loadshedding. Yet India sells Kashmir’s hydroelectric power to Rajasthan and other states. Kashmir could see escalating climate disaster; experts have long warned about its receding glaciers and other ecological fragilities, exacerbated by decades of military occupation. With the Indian government giving contracts to Indian companies to mine for minerals, Kashmir is further vulnerable as these companies do not adhere to environmental regulations, nor do they have knowledge of the local ecology. India’s contemporary colonisation is defined by surveillance technology, the arms trade, neoliberal resource extraction, criminalisation of all forms of dissent, and climate change.

Many countries around the world have their own Kashmirs, places they have subjugated either through overt forms of violence or through assimilating forms of control, and at times both.

Contemporary forms of colonialism exist across authoritarian and democratic governments. In the case of India, they exist in a country that claims to be the largest democracy in the world. The case of Kashmir not only challenges this claim but contests the idea of India altogether.