Staring down at his last sous in March 1743, Jean-Jacques Rousseau gathered up his courage and knocked at the door of Madame Dupin. As the out-of-wedlock daughter of an ex-Protestant draper-turned-financier, Louise Dupin was one of the wealthiest women in Paris. Her father, Samuel Bernard, had grown rich as one of the founding partners of the Compagnie de Guinée, and then immensely rich arranging loans to finance Louis XIV’s territorial wars. In the 1740s, the Dupins lived at the Hôtel de Vins in the stylish rue Plâtrière, where Madame Dupin hosted a distinguished salon. And it was there, in her private quarters, that she first received Rousseau. As he tells it in his Confessions (1782), he nearly wore out his welcome by immediately falling in love with her.

Portrait of Madame Dupin (c1736) by Jean-Marc Nattier. Courtesy Wikipedia

Rousseau unburdened himself to Madame Dupin in a letter, which she returned with a frostiness that nipped his festering passion in the bud. He nevertheless managed to recover his dignity and prove his merit by filling in briefly as governor to the Dupins’ ungovernable teenage son, Jacques-Armand Dupin de Chenonceaux. In 1745, Madame Dupin hired Rousseau ‘as a kind of secretary’. In this capacity, he spent most of his waking hours at the Hôtel de Vins or other properties owned by the Dupins, getting – in Rousseau’s own words – ‘fat as a monk’.

He was still in Dupin’s service when he composed, for a competition, the provocative essay that would launch his philosophical career. In A Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts (1750), Rousseau poured cold water on the Enlightenment’s progress parade. The enquiring minds of the Dijon Academy wanted to know ‘whether the restoration of the sciences and the arts has contributed to purifying morals?’ No, he said, it made everything worse. The progression of knowledge and development of the arts paved the way for conspicuous consumption, exploitation and war. In a second submission to the Academy’s essay contest, he went on an even deeper tear against civilisation, responding to the question: what about ‘the origin of inequality among men, and whether it is authorised by natural law?’ Yes, he allowed in the Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men (1755), equality was natural, but Thomas Hobbes, Samuel von Pufendorf, John Locke, etc have it all wrong. Man in the state of nature was a solitary creature. Primitive social organisation brought various forms of natural inequality to light. Civilisation progressed, usurpers invented laws to protect their ill-gotten gains, and inequality between the haves and the have-nots became legal and binding. The day will come, Rousseau warned, when tyranny will make us equal again – in our wretchedness.

Throw shade at the Enlightenment, expect to be catapulted into the blinding daylight of fame. Frenzied objections to the Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts hailed from all corners of Europe. In Paris, Rousseau was the talk of the town, harassed by visitors, accosted by strangers – all bent on throwing money at him. Though the Discourse on Inequality caused less of a stir upon publication, four decades later, Rousseau’s blazing eloquence was tripping off the tongue of Jacobin orators all over France. Given the timing, it is surprising that few scholars have stopped to wonder whether Rousseau’s fledging as a philosophe – at the none-too-precocious age of 38 – had anything to do with the six years he marinated in Madame Dupin’s project, quill to linen, taking dictation, making clean drafts, and trawling through stacks upon stacks of books for passages relevant to her enquiry. As it turned out, this failure of curiosity did not just envelop a woman philosopher in a cloak of invisibility. More broadly, it obfuscated the feminist origins of fundamental political concepts – equality, rights, contract – in a framework that denied women political subjectivity.

Granted, if Madame Dupin’s work remained unexplored for so long, it was mainly due to its difficulty of access. Dupin had not published her work, circulated it or even finished it. Her great-grandnephew Gaston de Villeneuve-Guibert published her short moral reflections on friendship, happiness and education in 1884. However, he punted on puzzling together the ‘discontinuous scraps’ of her larger project. These lay dormant until the 1950s, when Villeneuve-Guibert’s heirs hired a scholar to create an inventory of all Dupin’s papers before putting them up for auction. This scholar, Anicet Sénéchal, was the last person to see her work in progress in one pile. He called it ‘the work on women’, because a previous hand had scrawled ‘Ouvrage de Mad. Dupin sur les femmes’ across the cover of the top packet of folios. Of the nearly 3,000 folios, the majority pertained to the work on women: around 500 pages of drafts, most in Rousseau’s hand, with Dupin’s additions and corrections, and well over 1,000 pages of reading excerpts that Rousseau prepared for her. To extract maximum profit from the manuscripts, the auction house Drouot parcelled them up and scattered them to the highest bidders. Big chunks were purchased by municipal and university libraries in Switzerland, France and the United States. Smaller sections evaporated into private collections.

These ‘scraps’ tell the story of an evolving project. Dupin’s inspiration was On the Equality of the Two Sexes (1673), a small book published anonymously by François Poulain de la Barre, a Catholic priest of Cartesian convictions. Poulain set out to debunk the naturalness of men’s empire over women, just as Copernicus had decentred Earth in astronomy. Dupin echoes Poulain’s social Copernicanism in a ‘Preliminary Discourse’ – a kind of prospectus she wrote before she hired Rousseau. People long believed that ‘the Sun turned around the Earth’ and, analogously, the opinion of the inferiority of women endures ‘because it is not examined by reason, because we receive it in childhood, and because women, having no part in knowledge or industry, have almost no opportunity to establish their qualities and capacity.’

As her project progressed, however, Dupin reconsidered Poulain’s premise. Poulain consented ‘to a very general, very ancient prejudice’, Dupin observes, when he ‘could have attacked the very foundations of this prejudice, conceding neither its antiquity nor its universality.’ Dupin would heed her own advice. Whereas Poulain made his case sola ratione – by reason alone – she turned to the vast quarry of human history. To prove that women have wielded power in all times and everywhere, she extracts (with Rousseau’s help) a global roster of girl bosses from the period’s hugely popular travel narratives: empresses from China and Japan, queens from (what are now) Indonesia and Angola, regents from India and Portugal.

Masculine vanity builds a world according to its fantasies, then rewrites the past to its specifications

Dupin’s strategy anticipates the recovery work of the feminist historian of philosophy Eileen O’Neill in her landmark essay ‘Disappearing Ink’ (1998). O’Neill created an inventory of philosophical works published by Early Modern women philosophers ‘to overwhelm you with the presence of women in Early Modern philosophy’ – and to get you to wonder about their absence in subsequent histories of philosophy. O’Neill cites historical factors – the French Revolution, the professionalisation of philosophy – as suspects in the case of the disappearing ink. But Dupin, whose work on women did not disappear, because it had never appeared in the first place, had her own idea about what made women fade from history: a manly flavour of amour propre that she called ‘masculine vanity’.

Equal parts toxic masculinity and confirmation bias, ‘masculine vanity, which squanders no opportunity to put itself first’, is a funhouse mirror that makes men look bigger than they are and that squeezes women out of the picture. Successive generations are schooled at this ‘living tableau, in which only men have acted since time immemorial.’ If history is life’s teacher, as Cicero said, then for boys ‘modern history is a defence of masculine dignity and power’, whereas for girls, it ‘is a continual lesson in subordination’.

Self-interest sans self-awareness makes masculine vanity not just more nefarious than prejudice (as Poulain construed it) but lends it different explanatory power. Masculine vanity involves worldbuilding. It reaches into the future. ‘The tiniest foundation suffices to erect a grand edifice when it comes to vanity,’ Dupin muses, ‘since men rest the throne of their domination on the small difference of their strength compared to that of women.’ Negligible differences compound over ‘a long succession of time and chance’ to yield a nation in which queens never rule, and in which historians falsely claim that male rule has been the law of the land since the French were Franks. Masculine vanity builds a world according to its fantasies, then rewrites the past to its specifications. It is therefore not enough to go ferreting queens out of pigeonholes. Dupin’s thesis – ‘what subsists now against women is the accumulated injustice of several centuries’ – commits her to an analysis of this process.

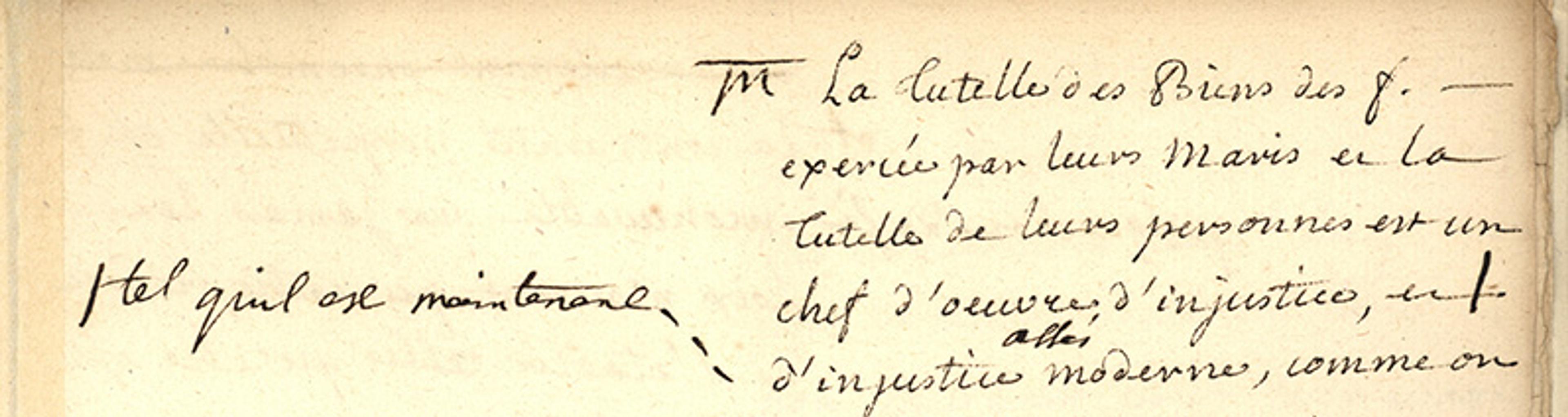

Dupin’s most important analysis of the accumulation of injustice is her examination of property law pertaining to marriage. Her claim is not just that ‘the tutorship of women’s property exercised by their husbands and the tutelage of their persons is a masterpiece of injustice,’ but that it is all the more illegitimate for being ‘a fairly modern injustice’. Let’s break this down.

First, the husband’s ‘tutorship’ of his wife’s property. What this means is that marriage is a transaction in which the wife’s property – her wealth along with ‘the rights and distinctions that accompany any inheritances she possesses’ – pass into her husband’s hands, to have and to hold, to own or to manage. In this arrangement, the religious ceremony celebrating their union is just window-dressing for a civil contract legalising her despoilment:

Marriage is ordinarily defined as a sacrament between two free people, of which the bride and groom are themselves the ministers, and the priest, just the witness. But what a ministry and what ministers! The groom and the bride arrive equal and free at the altar; one leaves with the property and freedom of the other, who leaves destitute and subjected. Meanwhile, the priest, as minister and witness, makes this strange transaction solemn and binding by uttering just a few words here and there, none of which even hint at what is actually happening.

Dupin likens the wildly asymmetrical terms of the modern marriage contract to a business arrangement in which one partner makes off with the lion’s share, while the other, entitled to none of the profits, is nevertheless liable for all the losses. Courts regularly invalidate these ‘leonine’ partnerships, Dupin points out, yet they uphold marriage.

Henry IV abrogated a law protecting married women’s assets from predation by spendthrift husbands

Second, the husband’s ‘tutelage’ of his wife’s person. Just as marriage dispossesses a woman of her property, it disenfranchises her of rights. ‘It is coolly stated that a woman is in the power of her husband, which not only means that none of her civil actions have any validity without the authorisation of her husband, but also that she is entirely in his dependence,’ Dupin writes. A husband needs his wife’s consent only to sell her property – and ‘he has so many ways of making her consent’ that this is just a formality. She, on the other hand, has to obtain his full legal authorisation to take out the smallest loan. Not to mention that a husband whose wife is convicted of adultery gains full ownership of her dowry and can lock her away in a convent, while a cheated-on wife can only weep.

Third, the ‘fairly modern’ character of this injustice. Things did not used to be this way. All the preaching and pontificating about wifely dependence masks ‘true usurpations that were arrived at only by degrees’. When did a husband with nothing to his name gain the right to pledge his wife’s assets for credit on the basis of her (coerced) consent to sell? No earlier than 1606, when Henry IV abrogated a law protecting married women’s assets from predation by spendthrift husbands. Since when has a legally mature wife had to have her financial dealings authorised by her legal minor of a husband? Only since 1608, when the president of the Parlement of Paris decided so. Modern marriage is a pastiche of political absolutism – ‘monarchical power since Cardinal Richelieu has been copied all the way into the home’ – resting on a caricature of Roman law. Its lettres de noblesse fake an unbroken lineage to the coemptio marriages of the Roman republic, in which husbands ‘purchased’ brides from fathers. What about the women who married with legal independence (sui juris) in classical Rome? Nope, nothing to see there.

Behold the magic of masculine vanity: ‘That men took over everything purely and simply: all well and good! But it is a gross imposture to base this usurpation on the incapacity of women, on nature, and on customs from time immemorial.’

Scholars like to debate Rousseau’s take on ‘the woman question’, but it is straightforward. ‘When woman complains … about unjust man-made inequality, she is wrong,’ he writes in Émile; or, On Education (1762). ‘This inequality is not a human institution – or, at least, it is the work not of prejudice but of reason.’ Rousseau dismisses Dupin’s entire work on women as a ‘complaint’ – without naming her – and disavows the work he did for her as nothing more than the cherry-picking of historical facts. Reacting to a point in Dupin’s chapter on strength, he concedes that: ‘There are countries where women give birth almost without pain and nurse their children almost without effort.’ But this proves nothing, he objects, for men in these countries ‘vanquish ferocious beasts, carry a canoe like a knapsack, pursue the hunt for up to seven or eight hundred leagues.’ Factoids plucked from their context, he insists, elevate unsound claims. Yet Rousseau’s repudiation in Émile of the work on women is its own exercise in selective reading. Notably, he has nothing to say about the long succession of time and chance that yielded inequality, about the unjust laws that instituted a leonine contract, or about the rewriting of history that burnished the flouting of natural law with the patina of antiquity.

‘Let us … begin by setting aside all the facts,’ Rousseau states at the outset of the Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men. He had learned, as Dupin’s chief cherry-picker, how poorly historical facts could perform in philosophical arguments. Better to summon the sublime sweep of his imagination. But this imagination had grown ‘fat as a monk’ on the books he had parsed for Madame Dupin for six years, and fertile with the feminist narrative he disavowed. His fact-free story of humankind’s emergence from the state of nature and formation of societies harks back to Poulain de la Barre’s ‘historical conjecture’ in On the Equality of the Two Sexes. Except that Rousseau substituted for Poulain’s Hobbesian free-for-all an era of solitary tranquility that might have lasted forever had one man not, on a fateful impulse, planted fenceposts. Eventually, the first society was born: the family, which produced ‘the sweetest sentiments known to man: conjugal love and paternal love’, redolent of the sweetness of Dupin’s Golden Age fantasy in her ‘Preliminary Discourse’: ‘It is plausible that at that time, there was no question of the inequality of merit between men and women and that sweeter and more essential sentiments occupied them, each one equally useful to society.’

Dupin condemned the most ordinary thing in the world – marriage – as a masterpiece of injustice

Through a sexual division of labour derived from Poulain, Rousseau parks women in a hut never to mention them again. From here on out, it’s a man’s world, but that world parallels the development of a woman’s story. ‘The first step towards inequality’ toddled in with public life, and each man ‘began to look at the others and to want to be looked at himself, and public esteem acquired a value.’ Behold the origin of masculine vanity! ‘From these first preferences were born on the one hand vanity and contempt, on the other shame and envy.’ For just as Dupin imagined that ‘men in multiplying, multiplied their passions,’ Rousseau insists that ‘a multitude of passions … are the work of society.’

As wants became needs, ‘the breakdown of equality was followed by the most frightful disorder’, only to be remedied by an ingenious swindle in which the rich persuaded the weak to commit to a social order that cemented their immiseration. ‘Such was, or must have been, the origin of society and laws, which gave new fetters to the weak and new forces to the rich, destroyed natural freedom for all time, established forever the law of property and inequality,’ and ‘changed a clever usurpation into an irrevocable right.’ With these words, Rousseau transformed the status quo into a scandal, just as Dupin had done when she condemned the most ordinary thing in the world – marriage – as a masterpiece of injustice.

And remember: she had done so via Rousseau’s pen. Rousseau did not just read Dupin’s words, as he read all the male philosophers he cites and scorns. He wrote them out. Here is the sentence just unpacked, in his neat round hand, with Dupin’s additions (indicated in italics): ‘But the tutorship of women’s property exercised by their husbands and the tutelage of their persons is a masterpiece of injustice, and such as it is now, a fairly modern injustice’:

‘De la puissance du mari’ by Louise Dupin, handwritten by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with additions by Dupin. Courtesy the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Based on the thick tranche of Dupin manuscripts acquired by the Harry Ransom Center (HRC) in Austin, Texas, the French professor Leland Thielemann at the University of Texas pointed out more than 40 years ago that, knowingly, unconsciously or even unwillingly, Rousseau had internalised Dupin’s core claim. The origin of his critique of the Hobbesian social contract, which locks in an absolute sovereign, was none other than her critique of the marriage contract, which imports absolute monarchy into the home. In the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau concurs with Dupin when he remarks that ‘it would be difficult to demonstrate the validity of a contract binding just one of the parties, in which one side granted everything and the other nothing, and which could only prove prejudicial to the one who commits himself.’ In The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau exposes the folly of such a contract by staging it as an oath:

Whether from one man to another, or from one man to a people, this discourse will always be equally mad: I make with you a convention all at your expense and all to my profit that I will observe as long as I please, and that you will observe as long as I please.

How not to hear in this laughable oath the vows exchanged at the altar in Dupin’s equally theatrical sketch of the groom who leaves flush with a new dependent’s assets, the bride who comes away destitute and subjected, and the priest who sprinkles some magic over the whole transaction to make it irrevocable? Rousseau retained the asymmetry of the leonine contract but swapped out the variables. The rich are to the poor in his Discourse on Inequality as husband was to wife in Dupin’s work on women.

Taking dictation and scouring books, he insists, were his only tasks. False modesty? Residual resentment, for sure

And you would never know it, for nowhere does Rousseau divulge the content of Madame Dupin’s project. Perhaps keeping mum was a condition of the work, one he respected far beyond the term of his employment, just as she never spilled the tea about the numerous babies he abandoned at the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés. After all, Dupin would have had good reason to request Rousseau’s discretion. A woman’s reputation was generally not enhanced by literary, scientific or philosophical ambition. Since a woman’s ‘dignity consists in her being ignored’, as Rousseau puts it harshly in Émile, she who takes her bel esprit public ‘is always ridiculous and very justly criticised.’ Several women well known to Dupin – the physicist Émilie du Châtelet, the novelist Françoise de Graffigny – published their work and averted ridicule thanks to anonymity. But, as a woman seeking justice for women, Dupin was doubly ridiculous, extra criticisable.

As for the nature of his work for Madame Dupin, Rousseau barely gestures to it. Underscoring the social hierarchy that conditioned their working relationship, he says that Dupin considered him diligent in manœuvre – menial labour. Taking dictation and scouring books, he insists, were his only tasks. False modesty? Residual resentment, for sure. Madame Dupin failed to recognise the genius of her workhorse. Performative disengagement, also. The tasks assigned to him kept his hands busy, while his mind remained unencumbered, independent, aloof.

Louise Dupin died just 11 days after Napoléon Bonaparte put the last of the revolutionary governments out of its misery. By then, her erstwhile secretary had been dead for more than 20 years, and rue Plâtrière had been rechristened rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau. For the next two centuries, masculine vanity yawned at her work on women. Between the Confessions, where he emphasises his purely mechanical contributions to Dupin’s project, and Émile, in which he discretely lampoons it as poorly reasoned and badly supported, Rousseau gave his readers little reason to be curious about it – or to wonder what he might have learned from his employer. All but a handful of scholars took their cue from Rousseau’s diffidence, even after Sénéchal published his 120-page inventory of Dupin’s papers in 1965 – and even after Thielemann distilled some stunning parallels from the HRC’s trove in 1983.

In all of Europe, Rousseau recalls in his Confessions, there were ‘but a few readers who understood [the Discourse on Inequality], none of whom wanted to speak about it.’ Was Dupin one of these silent readers? Historians usually turn to letters to eavesdrop on the reception of high-profile publications. Alas, Dupin reduced her correspondence to ashes following the declaration of the First French Republic in 1792. A document that survived nevertheless allows us to discern, however faintly, her consideration of her former secretary’s work.

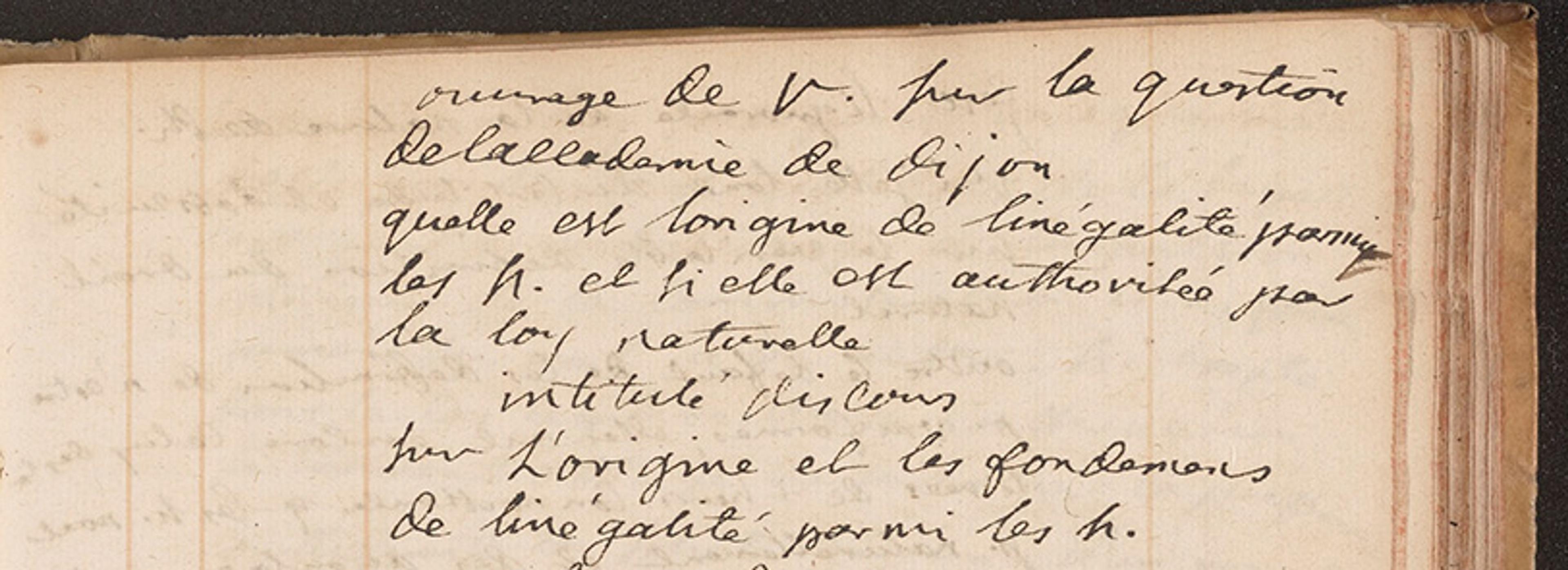

Unlike the hundreds of loose folios held in archives or pictured on the websites of French auction houses, this one is a bound notebook covered in vellum. It features distinct genres of record-keeping from the 1750s. Peruse it proceeding from one cover, and you find various household accounts. Purchases of salt and velvet are listed vertically, prices stacked to the right between vertical red lines for ease of tallying, while the contents of three wine cellars spill across the gutter on a horizontal axis. But if you flip over the notebook from the bottom, you encounter a mix of drafts and reading notes, mostly pertaining to ‘new books’ – from 1755 or slightly before.

The discontinuous scraps of the curious notebook are remnants of a non-meeting of philosophical minds

About 10 pages in from this direction, some familiar words lie sandwiched between 260 lbs of coffee, 1,700 livres tournois’s worth of printed cotton, and 515 bottles of Champagne. Albeit mangled by Dupin’s loping script, abbreviations and idiosyncratic spelling, the title is clear: ‘ouvrage de r. sur la question de laccademie de dijon quelle est l’origine de l’inegalité parmy les h. et si elle est authorisée par la loy naturelle intitulé discours sur L’origine et les fondemens de l’inégalité parmi les h.’ That is, ‘work of r. on the question of the academy of dijon what is the origin of inequality among m. and whether it is authorised by natural law entitled discourse on the origin and foundations of inequality among m.’

‘Inventaire de la cave/Comptes du ménage’ by Louise Dupin. Courtesy of the Milton S Eisenhower Library, the Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

A role reversal, then, with Madame Dupin now taking notes on her former secretary’s work. Yet the discontinuous scraps of the curious notebook are remnants of a non-meeting of philosophical minds, and of the mutually exclusive forms of equality they championed. On the accounts side of the notebook, luxe evinces the social stratification deplored by the spiritual father of every French revolutionary. Fire-coloured velvet, crimson satin, white damask, taffeta glossed in Italian rose, grey-white English moiré, iridescent gourgouran bespeak the opulence of decor and dress that padded Rousseau’s secretarial servitude from 1745 to 1751. His wages – between 800 and 900 francs per year the first two years – were a tiny fraction of the cost of the fabrics that rustled about him. Little wonder he celebrated his philosophical coming-out by shedding gold trim, stripping off white hose, ditching the fancy wig, and stoically embracing the theft of all 42 of his fine linen (under)shirts from a laundry line.

On the notes side of the notebook, nothing indicates that the nearly noble Dupin – whose father had himself painted by Louis XIV’s portraitist – recognised her secretary’s upcycling of her narrative. In the six pages she devotes to the Discourse on Inequality, she remarks on Rousseau’s ‘condescension’ (supériorité) towards Genevan matrons, observes his ‘great esteem for Hobbes’, and (mis)quotes the bit about relations of ‘weakness or power, wealth or poverty’ being produced by chance and ‘founded on piles of sand, etc’. Either she never got to his tale of how the rich tricked the poor into consenting to their permanent dispossession, or she did not deem it worthy of note.

So Dupin did not settle accounts, and Rousseau had the first and last word. Whether out of a surfeit of secretarial discretion, or to avert the shame of having succumbed to a feminist influence, he consigned Dupin’s account of the origin of inequality to the hut of his memory, granting her the dignity that consists in being ignored. The work on women would belong to the primitive ‘before’ of his philosophical ‘after’ – to an era of manual labour revolutionised by an essay prompt that he just happened upon. By shrouding his work for Madame Dupin in mists beyond philosophical time, Rousseau sealed her fate as a salonnière with the literary pretentions of a bel esprit – in other words, a nonentity in the history of philosophy.

The stakes, though, were far more monumental than the effacement of one feminist philosophe. Masculine vanity builds the world it longs to see, and Rousseau planted a fencepost not just around ideas he claimed as his own, but also, in so doing, around philosophy: what it would hold in, and especially what it would keep out. Despite its concern for power, equality, rights and contracts, Early Modern feminism is still seen today as a literary interloper in the field of political philosophy. This partition – and the consequent erasure of the feminist origins of inequality among men – is the upshot of a pattern of systemic forgetting that Louise Dupin was the first to identify and by no means the last to fall into. She was hopeful, though, and her own comeback story proves what she firmly believed: with a modicum of curiosity and a little elbow grease, sand can be brushed away, ink can be made to reappear, and fuller, more accurate histories can still be written.