As a seven-year boy, John Edwin Smith was taken by his father to see paradise. Living in a cramped tenement in Lewisham, southeast London, he had hitherto considered the high street’s clock tower the very edge of the universe. But one Sunday morning, a year after the end of the First World War, John was taken on an open-top bus ride for the first time. The journey took father and son through Catford and into the beginnings of what was then called the countryside: you’d have to travel a further 30-odd miles to find it today. Arriving at the bottom of Bromley Hill, ‘all very rural’, his father walked him through the mud and potholes of a building site to a house on the corner of Sandpit Road. ‘I was told that it was going to be my new home.’

Construction on the Downham Estate in 1925. Photo © The London Metropolitan Archives

The Smiths had arrived on the Downham Estate, one of eventually 13 ‘cottage estates’ built by the London County Council in the interwar years as part of a huge social and economic transformation of Britain, partly fuelled by the demands of those back from conflict that they not return to the terrible inner-city living conditions they’d left behind. A little more than 100 years ago, the scale of poverty and deprivation in London’s inner-city slums was dramatic. Scarlet fever and TB claimed many lives, and 25 people died of starvation every year in the East End in the run-up to war. The prime minister David Lloyd George, looking over his shoulder at the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, believed new houses and (something often overlooked by historians) attendant gardens could be the emollient to soothe potential uprisings: ‘Britain would hold out against the dangers of Bolshevism, but only if the people were given confidence, only if they were made to believe that things were being done for them.’

The winner of the London County Council Front Garden Competition at 1, Keedonwood Road, Downham Estate. Photo © The London Metropolitan Archives

Lloyd George’s ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ campaign would eventually lead to the building of 5 million new homes, more than 3 million in the private sector and more than 1 million in the public, before the outbreak of the Second World War. The majority of these came with approximately 400 square yards of something new householders and tenants had rarely had before… open space outside. And while this might seem a ‘nice add-on’ today, it was certainly not thought so at the time. The housebuilding campaign was primarily driven by disciples of the Garden City movement, which held that access to open space and land was vital for the health, physical and spiritual, of the population. New garden cities could bring people back to Mother Earth, a connection lost during two centuries of grinding industrialisation, while also protecting Britain’s rural idyll from overdevelopment.

Before we lose sight of them, let’s return briefly to Sandpit Road, six months after that bus trip, to see the Smiths in their newly situated land of milk and honey. Young John tells how he watched in amazement as his father, a bricklayer whose leisure time was extremely scarce, went to work on their tiny corner of this new Britain with gusto. In common with millions of others, what really motivated Mr Smith was creating a garden. And it was a particular kind of garden, one that would forever be snobbishly ridiculed and become associated with negative connotations that still haunt British suburbia. While the London County Council builders created small homes that new residents hitherto could only have dreamed about, what they also left outside was bare clay littered with building waste material. New dwellers of these cottage garden estates were thus confronted with an enormous new challenge. It did not deter them.

Here’s John again:

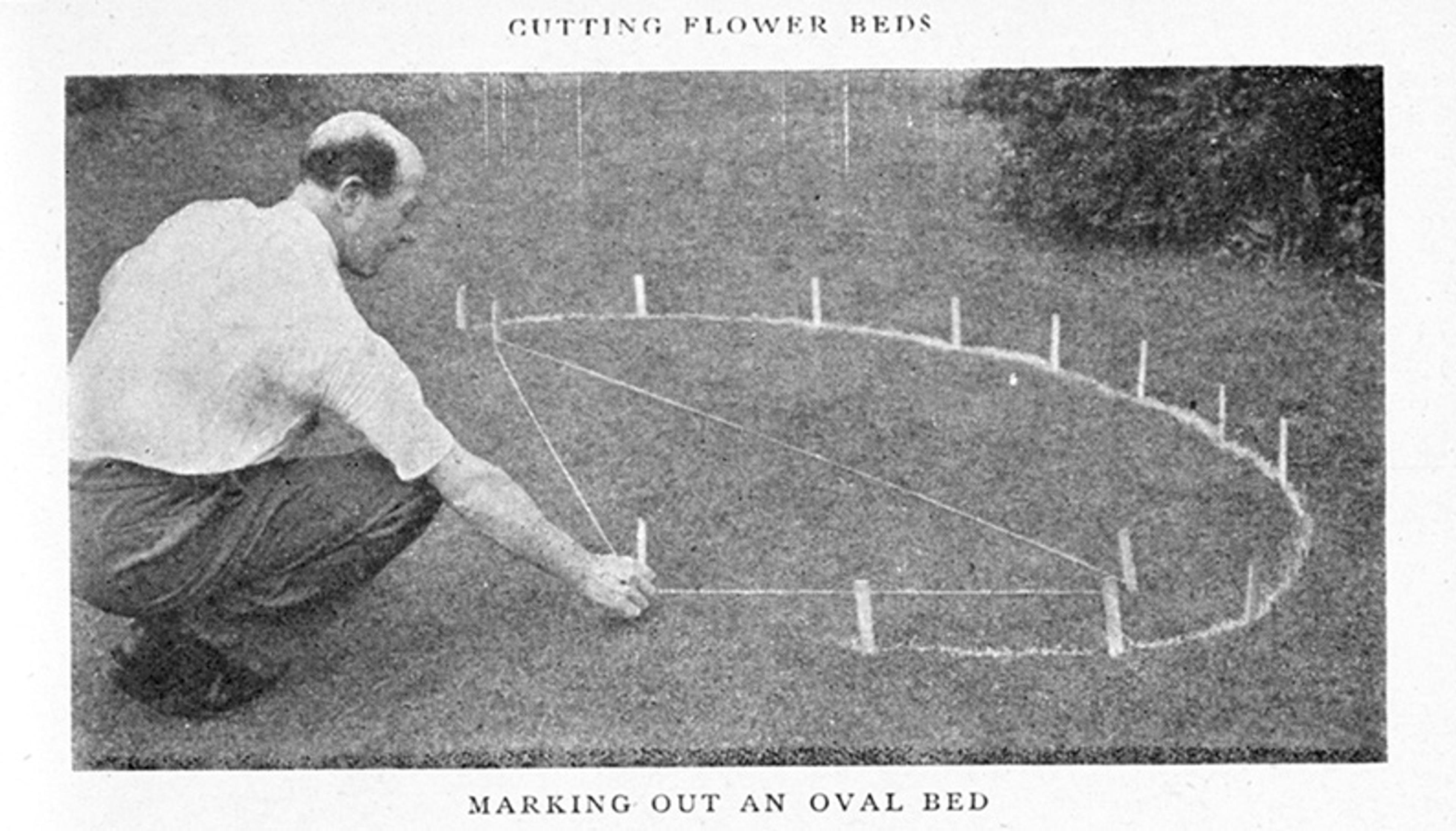

I remember him making a circular flower bed and ringing it with lumps of old stone and concrete that had been found among the building materials. I think my father took a few cuttings from the privet hedge and put them each side of the path leading to the front door, so that we had continuous privet hedge all round.

The privet hedge of suburbia had become a symbol of a curtain-twitching, dull new breed of Briton

The reaction of the Smiths and millions of other working-class families to their new suburban environments rarely surfaced at the time. John’s quotes above were recorded almost 70 years later as he looked back fondly on that momentous move. And yet this transformation of Britain and the way people lived was a contemporary prime-time, if very one-sided, debate in a manner arguably not seen since. Cultural commentators, Modern Movement architects, preservationists and Left-wing writers filled the airwaves with their damnations of the new spread of suburbia. Here’s the town planner Thomas Sharp with a, by no means extreme, view of the time:

Tradition has broken down. Taste is utterly debased… The town, long since degraded, is now being annihilated by a flabby, shoddy, romantic nature worship. That romantic nature worship is destroying also the object of its adoration, the countryside.

For Sharp and scores of middle-class theorists, the privet hedge of suburbia had become a symbol of a small-c conservative, curtain-twitching, dull new breed of Briton. The chance of real social change, the reimagining of a new country full of bold new high-rise cities populated by community-minded citizens, which also served to preserve rurality, was being trampled underfoot by the march of the suburban standard tea rose and garden gnome.

In the interwar years, it is estimated that a total of half a million acres of new garden were created. By the outbreak of the Second World War, around 80 per cent of English households were involved in some form of gardening activity. So for all the widespread criticisms, this was the real birth of the reputation of Britain as a ‘land of gardeners’. This was a time when the world war-weary, grey nation was being colourfully transformed, inch by hard dug inch. The spirit-uplifting nature of the humble flower was used as a weapon to raise horizons when the concept of beautification was twisting its way, like honeysuckle, into the thinking of another network of grassroots radicals fighting for a more egalitarian nation.

These new gardens, then, were contested spaces. Perhaps a metaphorical war of the roses is a good way into one strand of the argument. In the early 1920s, the standard tea rose together with a new breed of rambling rose became the popular go-to flower for the new suburbanites. These new breeds gloried in names like Betty Uprichard and Mrs Sam McGredy for the teas and Dorothy Perkins for the rambler. The former were tall and bold, exuding vibrant colour. But for the gardening cognoscenti, the early 20th-century country house-garden disciples of the designer Gertrude Jekyll, they were simply ubiquitous, blousy, vulgar even. A particularly popular wild rose with this upper-class horticultural set was a delicate aristocrat from the century before. She was called Madame Louis Lévêque and was set up in direct comparison to brash tea roses. It was a horticultural debate with clear class connotations, as even the names denoted. The Francophile gardening upper classes would be unlikely to invite brash Betty into their gardens but the demure Madame often held pride of place.

And yet, horticultural snobs had missed the point. Betty was bred for the gardens because she was hardy as well as beautiful; she was able to withstand brutal inner-city and suburban pollution. Madame would have stood little chance. Betty also helped these new gardeners create what became known as labour-saving gardens. Like Mr Smith, these new gardeners had very little time to indulge their new passions, working overtime just to pay rents for their new homes. Their gardens quickly became typical of the time and, actually, the bedrock of many British small gardens today.

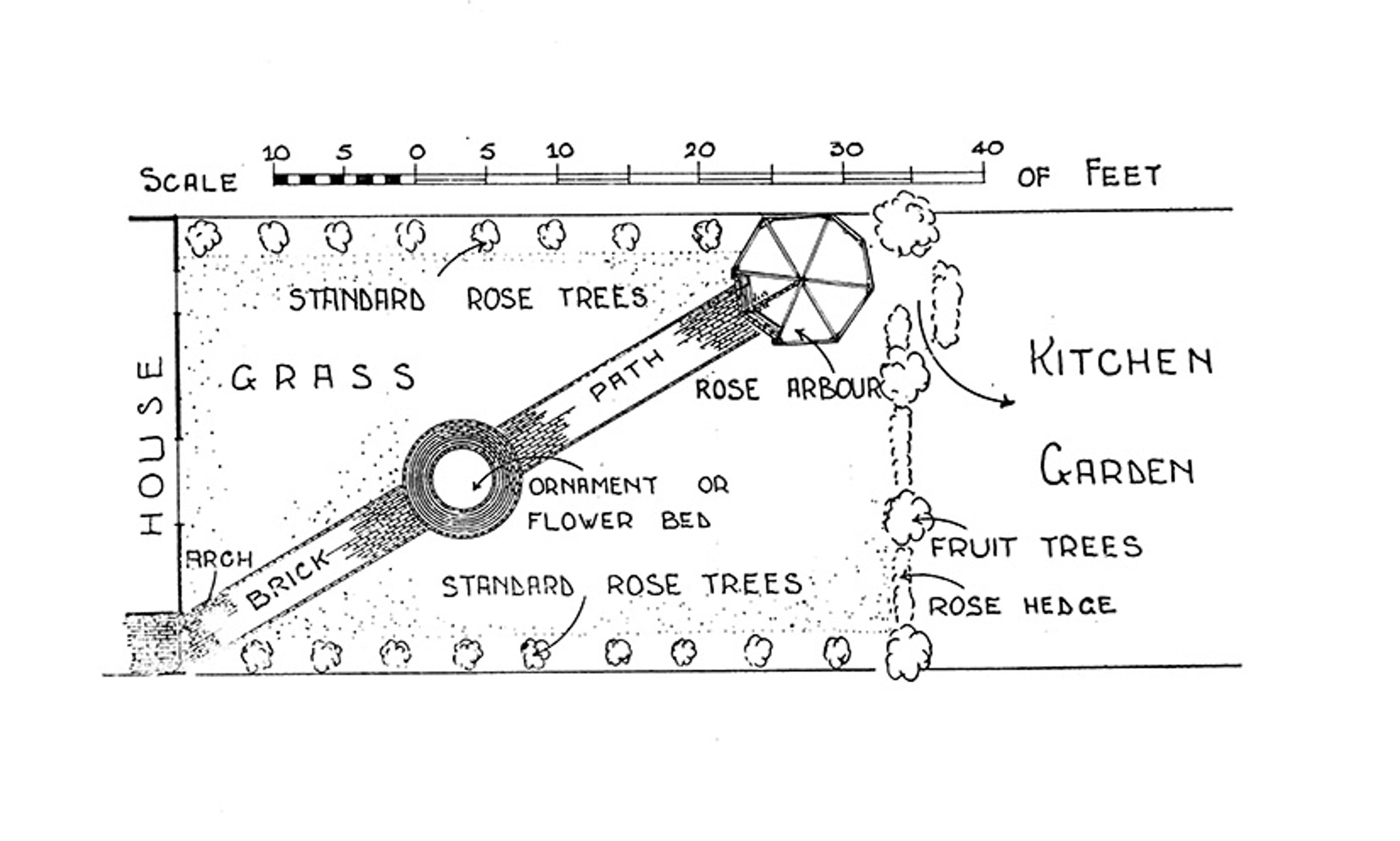

Order and compartmentalisation were important; here came the ubiquity of crazy paving, which added to the rigour of the garden, necessitating straight lines and delineated spaces, helped by rows of those tea roses or a simple archway draped with Dorothy Perkins. And, yes, the odd garden gnome and statuary began to appear. Originally imported from Germany as matchbox holders, gnomes were first used in the garden by the eccentric landowner Sir Charles Isham in 1847. Sir Charles used them to represent ‘earth spirits’ and they were wildly successful. Some 70 years later, though, and transferred to the suburban garden, they had taken on a very different meaning. The writer George Orwell led the charge against ‘rock-gardens with concrete bird baths and those red plaster elves’. Set among picturesque country estates, they were things of mystery and charm. But reproducing like rabbits across suburbia and exuding a sense of purpose, whether that be fishing, digging or pushing wheelbarrows, they were simply laughably vulgar. Despite this ridicule, these gardens were clearly an assault on a postwar dull grey world, with clean lines and bright, primary colours as weapons of transition.

There were genuinely held concerns that the suburbs were in danger of destroying Britain’s rural idyll

Orwell was not alone in this assault on the new suburbs. Writers and poets such as D H Lawrence and John Betjeman, leading town planners like Sharp and architects such as Clough Williams-Ellis and Bill Howell, many of them Modern Movement disciples of Le Corbusier and his vision of high-rise communities reaching far into the sky, lined up to damn this new way of living. It’s worth quoting another one of many fervent views from this loose collective to remind readers just how strong anti-suburban sentiment was among the intellectual class. Here’s Williams-Ellis in his book England and the Octopus (1928) – meaning the spread of the suburbs – describing suburbia as full of ‘mean and petty houses that surely none but mean and petty little souls should inhabit with satisfaction’.

The concerns were multifaceted. For some preservationists, there were genuinely held concerns that the suburbs, especially ribbon developments following road and rail lines out of London and other big cities, were in danger of destroying Britain’s rural idyll, even if it was arguable that this Elysium had never been available to the majority of new suburbanites anyway. For others, the problem was suburbia itself. For some Leftist architects and cultural theorists, the heroes of the First World War had failed to flex their political power to demand radical societal change and instead, within a few short years, had become shrunken in their suburban gardens, safe behind their privet hedges, ‘a modest, garden-concerned and common-sensical suburban male’, as David Matless puts it in Landscape and Englishness (1998). Modern Movement architects wanted Le Corbusier-influenced high-rise bold housing developments in cities, where people had a real sense of community involvement and whose space-saving natures meant rurality could return right into the heart of urbanity. Gardens simply didn’t count in this town-and-country reckoning.

Bill Howell, a Modern Movement architect who helped to design the Alton Estate in southwest London, perhaps the closest Britain ever got to Le Corbusier’s unrealised ideal of Ville Radieuse, explained his thinking behind his work thus:

We felt this would turn the tide back from the suburban dream … this is what we must do; we don’t want to rush out and live in horrid little suburbs and semi-detached houses.

Frankly, there was never any danger that the Marlborough College-educated son of a diplomat was ever going to have to live in suburbs nor, for that matter, his own tower block creation at Alton, which has had, at best, a chequered history full of stories of unhappy residents and unrealised regeneration plans.

But being on the wrong side of history as Howell, Williams-Ellis and their cohorts have been – while, one by one, their tower blocks have been demolished or drastically altered – does not change the fact that the sound and fury they created still resonates. Although more than 75 per cent of Britons live in suburbs today, those curtain-twitching, dull stereotypes still exist. What they also do is obscure the real origin story of the interwar suburban garden as hinted at earlier. For this story, a forgotten figure in early 20th-century garden and landscape history serves as a perfect conduit.

Richard Sudell showing how to cut a typical circular bed in lawns for tea roses or pansies, sweet peas or snapdragons. Courtesy the author

Born in Lancashire in the northwest of England in 1892, Richard Sudell was a working-class gardener from the age of 14. He was a remarkable character: briefly a Kew Gardens trainee, he was imprisoned as a First World War conscientious objector and would, against the odds, go on to play a leading role in the foundation of professionalised landscape architecture. A Quaker socialist, Sudell promoted suburban gardens both deep down in the real soil of practice and as a prolific journalist. Despite his relative lack of education, he built an audience of millions in magazines and newspapers (he was gardening editor of the working-class newspaper the Daily Herald, which was then, with 2 million readers a month, the biggest newspaper in the world). He wrote 47 books serving an almost unquenchable thirst for new suburban gardeners to be told in plain, practical, language how to create their new plots, understand the rhythms of the seasons, and discover which flower, shrub, tree or vegetable worked best in which soil.

As importantly, in contrast to Howell and Co, he would join with other nonconformist Christians, radicals and politicians to form a different network that was determined, with or without the government of the day, to help alleviate the crushing levels of poverty that were blighting the nation’s inner cities. New homes were one weapon, advances in healthcare were another but so too, with equal billing, was fresh air, open space, exercise and gardens. Given his war record, it might be thought ironic that, after prison, Sudell moved into the Roehampton Estate, another of London County Council’s garden suburbs built under the government’s Homes Fit for Heroes subsidies but, once there, his evangelical belief in the power of horticulture was unstoppable.

The annual London Garden Championships was as successful as the upmarket Chelsea Flower Show

Sudell formed the Roehampton Estate Garden Society as soon as he moved in with his first wife Emily, and spent the next two years turning his neighbours – many still suffering the health effects of inner-city slum living – into a fearsome gardening army. He was by that time already the secretary and driving force of a now little-known but then hugely influential organisation called the London Gardens Guild (LGG). Within a short space of time, virtually every borough of London had an associate branch of the LGG. Tens of thousands of inner-city and suburban garden members could take advantage of cut-price seeds and communal lawnmowers, and enter competitions for best garden, street, window box and so on.

A basic labour-saving garden design from Sudell’s book The Town Garden (London, 1950). Courtesy the author

By the outbreak of the Second World War, some 50,000 entries were submitted for what was now called the annual London Garden Championships, set up by Sudell less to encourage competition than to motivate householders to play their part in beautifying their neighbourhoods. Subsequently, it was decided to showcase winners of this championship in an annual exhibition in which the best gardens would be recreated in miniature. It became so popular that huge queues formed every year. At the time, it was as successful as the upmarket Chelsea Flower Show, now a worldwide horticultural behemoth. But the championships have since been forgotten, and the LGG became the National Gardens Guild before the outbreak of war.

In the Guild, Sudell formed a strong bond with a remarkable woman called Ada Salter who, together with her husband Alfred, conducted a decades-long campaign to lift the people living on the fetid dockside streets of Bermondsey in southeast London out of abject poverty. The Salters were Quaker socialists and local politicians: Alfred was a brilliant doctor who ran a free surgery for residents, and served as the MP for Bermondsey for many years; and Ada was the first ever female mayor in London. One of Ada’s innovations was the establishment of a Beautification Committee that had as much power as any other on Bermondsey Council. With Sudell’s advice, this committee planted cherry trees and flowers wherever they could, moved old gravestones to the edge of churchyards so children could have somewhere to play, and promoted garden competitions. The Salters’ campaigning cannot be separated from the motivations of supporters of suburban gardens of the period. They are all part of the same movement, its ethos and philosophy lost in time, drowned out by other narratives.

Not content with these, almost literal, grassroots campaigns, Sudell was also the key founder of the Institute of Landscape Architects (now the Landscape Institute), working alongside key British figures such as Geoffrey Jellicoe, Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin to position landscape architecture at the centre of the reimagining of Britain after the wars. That this hope was forlorn, as attempts to create a national planning policy were consistently thwarted by successive disinterested governments, did not stop Sudell and others constantly lobbying for landscape architecture to be placed at the centre of big postwar reconstruction projects.

One such defeat was the complete omission of landscape architects from the planning of the first stages of the M1 motorway heading from London to Leeds in the north of England. Without landscape architects, Britain’s first motorway stretched along brutal straight lines with no acknowledgement of the countryside through which it passed. Its clumsy bridges were viciously attacked by critics who compared the road unfavourably with German autobahns being built at the same time, which smoothly followed the contours of the land.

The residents of this new suburbia are still missing from the history of the time

Nevertheless, until his death in 1968 at the age of 76, Sudell clung to the belief that gardens and landscape were the crucial foundation stones of a more civilised, egalitarian society, long after he must have known that such hopes for a new postwar beginning had vanished. For Sudell, the poorest members of society – not just those who could afford it – had the right to escape from what he described as the ‘turmoil of the day’ or their ‘exclusion from the world’ in however small an open space. For Sudell, it was as simple as the language in his books:

Beauty is one of the greatest forces in the world, it is the power which can move mountains and in striving after beauty, we are striving after the sublime. Let us then turn to our gardens both to seek freshness of mind and to add beauty to the world.

Given that we have seen how the residents of this new suburbia were largely missing from the debate and are still missing from the history of the time, perhaps it is fitting that we should travel a short distance further east from Downham to witness the testimony of Joyce Milan. As a teenager, she’d moved with her parents to the Page Estate in Eltham, south London shortly after the First World War. Her mother never again travelled far from that London County Council cottage estate, considering ‘she always felt she had her own bit of country’ there. Almost 70 years later, Joyce could still marvel at the enthusiasm with which her parents began carving out their new lives and almost catch the faint scent of her mother’s rambling rose, a breed derided by the cognoscenti but loved by the suburbanite:

My parents set about developing a garden, something they had never known but longed for. Mum was mainly in charge of the operation and it was remarkable what she achieved over the years. There was a large area of ground, so firstly a crazy-paving path was laid from broken pieces of plaster from the walls of the First World War hutments being demolished. Halfway along, a rustic arch was erected, which later supported huge bunches of Dorothy Perkins roses in the summer. In the right-hand centre was a circular rose-bed with fragrant blooms of every colour.

Behind the Privet Hedge: Richard Sudell, the Suburban Garden and the Beautification of Britain (2024) by Michael Gilson is published by Reaktion Books.