English spelling is ridiculous. Sew and new don’t rhyme. Kernel and colonel do. When you see an ough, you might need to read it out as ‘aw’ (thought), ‘ow’ (drought), ‘uff’ (tough), ‘off’ (cough), ‘oo’ (through), or ‘oh’ (though). The ea vowel is usually pronounced ‘ee’ (weak, please, seal, beam) but can also be ‘eh’ (bread, head, wealth, feather). Those two options cover most of it – except for a handful of cases, where it’s ‘ay’ (break, steak, great). Oh wait, one more… there’s earth. No wait, there’s also heart.

The English spelling system, if you can even call it a system, is full of this kind of thing. Yet not only do most people raised with English learn to read and write it; millions of people who weren’t raised with English learn to use it too, to a very high level of accuracy.

Admittedly, for a non-native speaker, such mastery usually involves a great deal of confusion and frustration. Part of the problem is that English spelling looks deceptively similar to other languages that use the same alphabet but in a much more consistent way. You can spend an afternoon familiarising yourself with the pronunciation rules of Italian, Spanish, German, Swedish, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish and many others, and credibly read out a text in that language, even if you don’t understand it. Your pronunciation might be terrible, and the pace, stress and rhythm would be completely off, and no one would mistake you for a native speaker – but you could do it. Even French, notorious for the spelling challenges it presents learners, is consistent enough to meet the bar. There are lots of silent letters, but they’re in predictable places. French has plenty of rules, and exceptions to those rules, but they can all be listed on a reasonable number of pages.

English is in a different league of complexity. The most comprehensive description of its spelling – the Dictionary of the British English Spelling System by Greg Brooks (2015) – runs to more than 450 pages as it enumerates all the ways particular sounds can be represented by letters or combinations of letters, and all the ways particular letters or letter combinations can be read out as sounds.

From the early Middle Ages, various European languages adopted and adapted the Latin alphabet. So why did English end up with a far more inconsistent orthography than any other? The basic outline of the messy history of English is widely known: the Anglo-Saxon tribes bringing Old English in the 5th century, the Viking invasions beginning in the 8th century adding Old Norse to the mix, followed by the Norman Conquest of the 11th century and the French linguistic takeover. The moving and mixing of populations, the growth of London and the merchant class in the 13th and 14th centuries. The contact with the Continent and the balance among Germanic, Romance and Celtic cultural forces. No language Academy was established, no authority for oversight or intervention in the direction of the written form. English travelled and wandered and haphazardly tied pieces together. As the blogger James Nicoll put it in 1990, English ‘pursued other languages down alleyways to beat them unconscious and rifle their pockets for new vocabulary’.

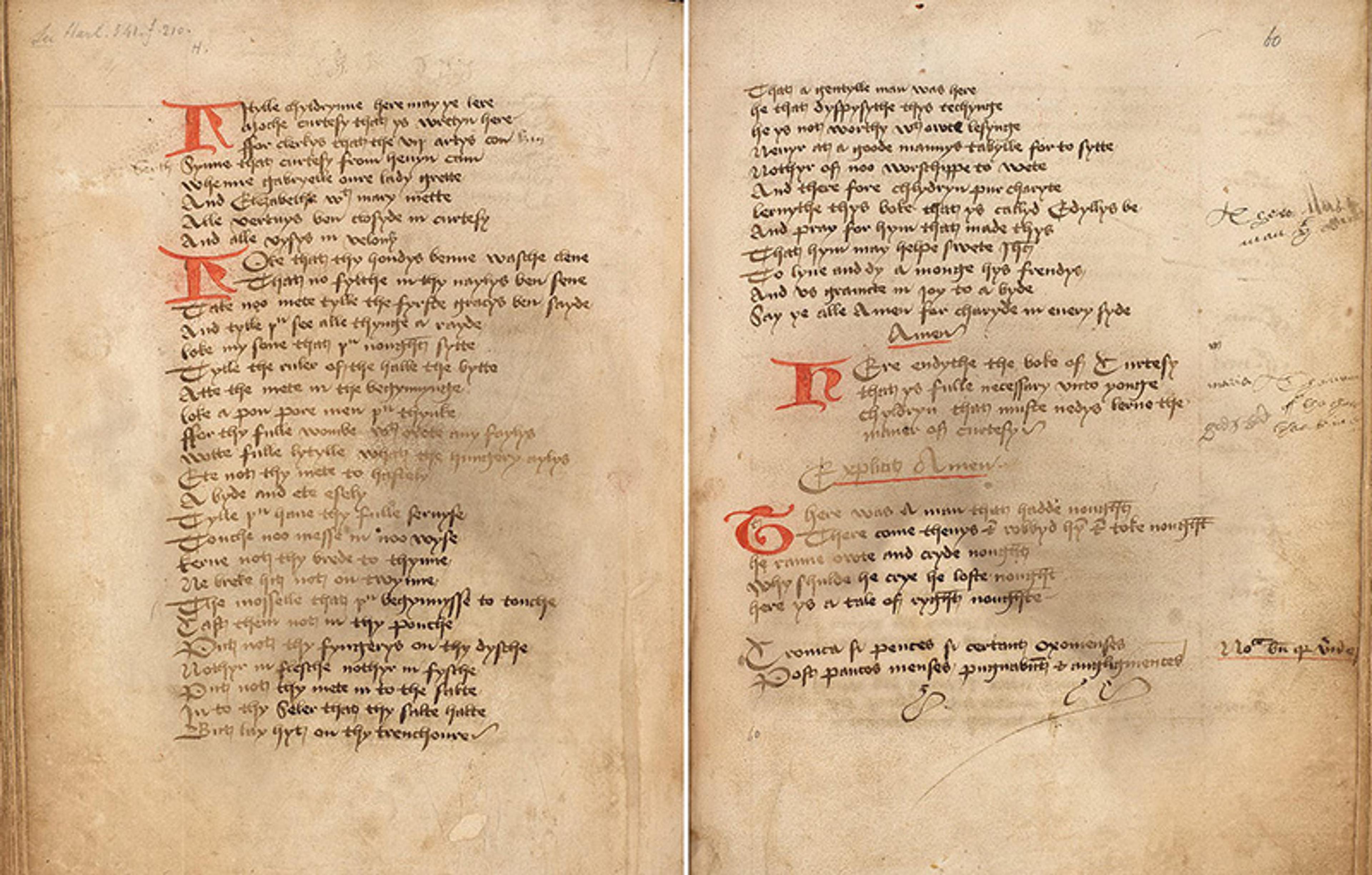

Plus ça change. The opening pages of The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke, an instructional book of table manners dating from around 1480 and written in Middle English. Amongst other directives, children are told Bulle not as a bene were in thi throote (Don’t burp as if you had a bean in your throat) and Pyke notte thyne errys nothyr thy nostrellys’(Don’t pick your ears or nose). Courtesy the Trustees of the British Libray

But just how does spelling factor into all this? It wasn’t as if the rest of Europe didn’t also contend with a mix of tribes and languages. The remnants of the Roman Empire comprised Germanic, Celtic and Slavic communities spread over a huge area. Various conquests installed a ruling-class language in control of a population that spoke a different language: there was the Nordic conquest of Normandy in the 10th century (where they now write French with a pretty regular system); the Ottoman Turkish rule over Hungary in the 16th and 17th centuries (which now has very consistent spelling rules for Hungarian); Moorish rule in Spain in the 8th to 15th centuries (which also has very consistent spelling). True, other languages did have official academies and other government attempts at standardisation – but those interventions have largely only ever succeeded at implementing minor changes to existing systems in very specific areas. English wasn’t the only language to pick the pockets of others for useful words.

The answer to the weirdness of English has to do with the timing of technology. The rise of printing caught English at a moment when the norms linking spoken and written language were up for grabs, and so could be hijacked by diverse forces and imperatives that didn’t coordinate with each other, or cohere, or even have any distinct goals at all. If the printing press had arrived earlier in the life of English, or later, after some of the upheaval had settled, things might have ended up differently.

It’s notable that the adoption of a different and related technology several hundred years earlier – the alphabet, in use from the 600s – didn’t have this disorienting effect on English. The Latin alphabet had spread throughout Europe with the diffusion of Christianity from the 4th century onward. A few European vernacular languages had some sort of rudimentary writing system prior to this, but for the most part they had no written form. For the first few hundred years of English using the Latin alphabet, its spelling was pretty consistent and phonetic. Monks and missionaries, beginning around 600 CE translated Latin religious texts into local languages – not necessarily so they could be read by the general population, but so they could at least read aloud to them. Most people were illiterate. The vernacular translations were written to be pronounced, and the spelling was intended to get as close to the pronunciation as possible.

Often the languages these monks and missionaries were trying to transcribe contained sounds that Latin didn’t have, and there was no symbol for the sound they needed. In those cases, they might use an accent mark, or put two letters together, or borrow another symbol. Old English, for example, had a strange, exotic ‘th’ sound, for which they originally borrowed the thorn symbol (þ) from Germanic runes. They later settled on the two-letter combination th. For the most part, they used the Latin alphabet as they knew it, but stretched it by using the letters in new ways when other sounds were required. We still use that sound, with the th spelling, in English today.

English was at home in the kitchen, the workshop, the marketplace, but less sure of itself in other registers

Writing was a specialised skill handled by dedicated scribes. They were trained by other scribes, who in turn passed on their spelling conventions. Different monasteries might have had different styles or habits for representing English sounds, and there were dialects and variations in pronunciation in the spoken language as well – but a written standard and eventually a whole literature emerged.

That tradition was broken after the Norman invasion in 1066. For the next 300 years or so, with a few exceptions, written English disappeared entirely. French was the language of the conquerors, and became the language of the state and all its official activities. Latin remained the language of the Church and education. English was the spoken language of daily life for most people, but the social class that had previously maintained and developed the written standard for English – landholders, religious leaders, government officials – had all been replaced.

English began its return as a written language in the 14th century. Over generations, it had crept back in among the nobility, as well as the clergy, although French and Latin were still the languages of educated and official pursuits. By then, English had changed. A few centuries of language evolution had led to different pronunciations. And Old English writing habits had been lost. As English started to make its written comeback, these people found themselves not only trying to figure out how to spell English words but also reaching for English ways to say educated, official things. English was completely at home in the kitchen, the workshop, and the marketplace, but less sure of itself in other registers. Grabbing the nearest convenient French word was often the solution. Things such court proceedings, government decrees, property ownership documents and schooling relied heavily on French vocabulary to fill in the gaps where English was out of practice. Words such as govern, judge, office, punish, money, contract, number, action, student and many others became part of the vocabulary of English official life – and then of everyone, as most people had some sort of interaction with officialdom.

Prior to the Norman conquest, Old English predominated, a thoroughly Germanic cousin of Dutch and German. To a speaker of Modern English today, it’s nearly unrecognisable as English, and requires translation to understand. In the next few hundred years after the conquest, it evolved into Middle English – still Germanic, but less thoroughly so, as grammatical endings disappeared and French vocabulary flowed in. Middle English looks much more like the English we know.

By the time written English started coming back, around 1300, there was no general standard for spelling. People, taken from French peuple, might be spelled peple, pepill, poeple or poepul. Beauty, from French beauté, might be bewtee, buute or bealte. It didn’t help matters that, at the time, French also had inconsistent spelling. All the vernaculars of Europe were on early, wobbly footing with respect to developing a consistent standard as they moved toward their own written tradition and away from Latin as the only choice. Then came the printing press.

Moveable type was invented in Europe by Johannes Gutenberg c1450. It involved making letters from metal alloys and setting them in a print tray-bed, inking them, and then pressing paper over the top to make an imprint – saving hours compared with laborious manual transcription. The earliest works printed with this new technique were in Latin, but printers soon spotted the potential market for books in vernacular languages, and began making them in great numbers. English got off to an early start: an enterprising merchant named William Caxton set up the first English press in 1476. This followed the success of an English translation he had printed while working in Bruges. There were no style guides, no copyeditors, no dictionaries to consult.

Moveable type was a wonderful invention: once the type had been set, you could print off as many copies as you wanted. But setting the letters, or pieces of type, into lines, and then pages, was intense, specialised labour. You had to spend years learning the trade. For his new press, Caxton brought typesetters back with him from the Continent, and some didn’t even speak English all that well. They set type working from manuscripts that already had quite a bit of variation, and the overriding priority was getting them set quickly.

Some standards did spread and crystallise over time, as more books were printed and literacy rates climbed. The printing profession played a key role in these emergent norms. Printing houses developed habits for spelling frequent words, often based on what made setting type more efficient. In a manuscript, hadde might be replaced with had; thankefull with thankful. When it came to spelling, the primary objective wasn’t to faithfully represent the author’s spelling, nor to uphold some standard idea of ‘correct’ English – it was to produce texts that people could read and, more importantly, that they would buy. Habits and tricks became standards, as typesetters learned their trade by apprenticing to other typesetters. They then often moved around as journeymen workers, which entailed dispersing their own habits or picking up those of the printing houses they worked in.

Some spellings got entrenched by being printed over and over again in widely distributed texts, very early on

Standard-setting was only partly in the hands of the people setting the type. Even more so, it was down to a growing reading public. The more texts there were, the more reading there was, and the greater the sensibility about what looks right. Once that sense develops, it can be a very powerful enforcer of norms. These norms in the literacy of English speakers today are so well entrenched that simple adjustments are very jarring. If ai trai tu repreezent mai akshuel pronownseeayshun in raiteeng, yu kan reed it, but its difikelt and disterbeeng tu du soh. It just looks wrong, and that feeling of wrongness interrupts the flow of reading. The fluency of reading depends on the speed with which you visually identify the words, and the speed of identification increases with exposure. The more we see a word, the more quickly we recognise it, even if its spelling doesn’t match the sound.

Some spellings got entrenched this way, by being printed over and over again in widely distributed texts, very early on. The word ghost, which had been spelled and pronounced gast in Old English, took on the gh spelling under the influence of Flemish-trained compositors. It was such a commonly encountered word in English text, particularly in the phrase holy ghost and other translations of Latin spiritus, that it just began to look right.

Other spellings arose, and were then cemented through the power exerted by the visual shape of similar words. The existence of would and should, for example, brought about the spelling of could. Would and should were once pronounced with the ‘l’ sound, as they were the past-tense forms of will and shall. Could, however, was never pronounced with an ‘l’; it was the past tense of can. Could was coude or cuthe. Then the visual power of would and should attracted could to their side. At printing’s rise, the ‘l’ sound was already often absent from the pronunciation of would and should, so the ‘l’ was less a cue to pronunciation than to word type. Could is a modal verb, same as would and should. There was no explicit intention to make them look the same, but the frequency of their appearance nudged them toward ending up that way.

Visual patterns strengthened their hold on spelling in other languages, too. The many homophones and silent letters in French arose from letters that represented sounds that used to be pronounced, but hung on in the writing system after they were no longer spoken. And since French was a Romance language with its roots in Latin, and literacy in French often went hand-in-hand with literacy in Latin, Latin spellings could reinforce French spellings that had lost phonetic justification. For example, in speech, cent and sang might be pronounced the same, but there was also the implicit knowledge that cent came from centum and sang came from sanguinum. This Latin connection served as a reference point that helped stabilise French spelling, even when it was disconnected from pronunciation.

Had the Norman invasion not interrupted the literary tradition of Old English, we might have ended up with a similar situation – a spelling system with silent letters and shifted sound values, but grounded in the spellings of their earlier forms. Old English would have continued to be the basis of the writing tradition that would have later been set into type. Instead, we had a number of parts, moving and changing independently from each other, often with no anchor at all.

What’s more, in the years when printing was slowly establishing and fortifying spelling habits, English was undergoing what’s now called the Great Vowel Shift. In broad terms, over the course of a few centuries, sounds changed and vowels moved around. Words such as name and make, for example, once had an ‘ah’ vowel as they do in German name and machen, or English father. During the Great Vowel Shift, it moved to more of an ‘eh’ vowel as in bed, and eventually to the ‘ay’ where it is today. But the words affected in this way continue to be spelled with the ‘a’ of father.

Words that ended up with an oo spelling generally used to be pronounced with a long ‘o’ sound. Moon and book both used to sound something like moan and boke; the two o’s, quite logically, represented a long ‘o’, before moving to an ‘u’ sound, as in June. However, sometimes the long vowel became a short vowel: eg, the more lax ‘u’ vowel, as in push. Moon (also goose, food, school) ended up with the June vowel, while book (foot, good, stood) with the push vowel. These changes happened at different times in different places. For some words (roof), the change hasn’t completely gone through, and still wavers (at least in my own Midwestern US dialect) between the two pronunciations. In some places in Scotland and the north of England, moon, book, goose and foot still have the same vowel.

The changes that came to be grouped under the Great Vowel Shift were gradual and went unnoticed as they were happening. When an English speaker sat down to write something at the end of the Middle Ages, the way they wrote it could depend on where they lived and what the dialectal pronunciation of vowels was there. It would also depend on what they had read and incorporated into their spelling habits. When a printer was setting type for that writing, they had their own pronunciation and spelling preferences. When a piece of writing was set in type and spread to other towns, it would be received by people of varying literacy levels, and that would influence how it was incorporated into their habits. In other words, there was tremendous variation at each of these waystations on the journey to being read. When a text was set in type and distributed, it had the effect of propagating the habit it represented, but how much it propagated depended on how widely it was distributed and where. Which specific aspects of the habit would stick and which fall away? The answer could be some or none. The result, ultimately, is a very irregular habit.

Writing attaches to language in the way that the fork is a technology that attaches to our eating habits

If English had been later to the technology of printing, further behind in the expansion of literacy, it might have been able to approach the development of its spelling system with a cleaner slate and a more stable idea of what was to be represented. But when a tool comes along, you don’t wait to figure out the optimal way to use it or worry about what the effects of using it might eventually be. Instead, you just start.

When a technology spreads, so does a habit of using it. Before we had printing, we had writing. Can we go back further? Isn’t human language itself a technology? This is arguable, a philosophical question. I would say no. In any case, language is much, much closer to our very natures as humans than is any invented or discovered tool passed along for practical problem-solving. Put a group of humans without a language together (as has happened in some cases with Deaf communities) and they will do language. A language will emerge from what they do.

But they won’t necessarily come up with writing. Writing is unquestionably a technology. It attaches to language in the way that the fork is a technology that attaches to our eating habits. Eating is undeniably a necessary part of our nature. The fork is a recent, unnecessary (no matter how useful) innovation. That analogy doesn’t go much further. There are very few things that capture the relation between language (the behaviour) and writing (the technology that represents the behaviour). It’s hard to find a good analogy. The point is that the eating happens whether we have the fork or not. Language happens whether we have writing or not.

When we first got the technology of writing, the people who used it represented a tiny fraction of the speaking population, in most cases for hundreds of years. Throughout the history of writing, most people have been illiterate. It was the technology of printing that made it possible to put writing into widespread use. The written word got cheaper and more plentiful. People had the access and exposure necessary to learn, practise and become literate. That access and exposure was created, in stages, by the competing and conflicting demands of history. That history and its lumps, bumps, silent letters and all, was pressed in with metal and ink.