On the surface, the language we use to describe landscapes and buildings has little in common with the ways we think about our social worlds. A mountain range has little in common with a family; the design of a city is nothing like a colleague – or so it seems. But if that is true, then why do we use spatial and architectural metaphors to describe so many of our human relationships? Good, trusted friends are described as ‘close’, regardless of their physical proximity, and a loved one on the other side of the world may feel ‘nearer’ to you than someone you live with. You might have an ‘inner circle’ of friends or feel ‘left out’ from the circles of others. A colleague with ‘higher’ status may seem to be ‘above’ you and those with ‘lower’ status may be ‘below’. There is even something architectural about the way we speak of ‘setting boundaries’ or ‘walling someone off’.

Without much thought, we employ a whole library of spatial and architectural metaphors to explain our social worlds – and not just for our personal relationships. These metaphors are foundational for social thought at the societal level, too. We describe some groups of people as ‘marginalised’ (pushed aside) or ‘oppressed’ (pushed down), and society itself is said to have a ‘structure’ to it, as though it were assembled like a skyscraper.

Why do social relationships form distinct geometries in our minds? In the past few decades, research has shown that these metaphors are not merely idiosyncratic uses of language. Instead, they reveal something fundamentally spatial about how we experience our social lives. And this leads to a radical possibility: if we make sense of our friendships, acquaintances, colleagues, families and societies through spatial relationships, could architectural concepts – the intentional design of space – become tools for creating new metaphors for social and political thought?

In the past 40 years, psychologists and linguists have demonstrated that these spatial metaphors are indeed more-than-metaphoric. In the 1980s, the philosopher George Lakoff and the cognitive linguist Mark Johnson showed that metaphors referencing bodily experiences in space structure how we think and speak about abstract social ideas: in English, love is sometimes expressed as a ‘journey’; the truth is something we ‘see clearly’. But it wasn’t until the mid-2000s that Lakoff and the neuroscientist Vittorio Gallese began to more boldly assert that the bodily states referenced in metaphors, such as ‘love is a journey’, involve simulations of the same sensation and perception networks engaged when those states – in this case, travelling – were first experienced. This means that, when we describe our extroverted friend as ‘lighting up the room’, the same part of the brain that tracks luminance levels in our environment (the visual cortex) reactivates during metaphor comprehension to simulate an image of a room lighting up, helping us understand an otherwise abstract comment about someone’s ‘bright’ personality. ‘Imagining and doing,’ Gallese and Lakoff have suggested, ‘use a shared neural substrate.’ (In other words, ‘thought is an exploitation of the normal operations of our bodies.’)

Embodied experiences with objects in physical space seem to provide helpful conceptual structures that we map onto our relationships. Spatial metaphors are the result of this process. We all have first-hand experiences of interacting with objects in space. We have reached out to grab something on a table in front of us, moved to catch something flying in the air, and failed to grasp something beyond our reach. Using these embodied experiences of proximity as reference points, our brains simulate the positions of people as ‘near’ or ‘far’ in an imagined ‘social space’. But how deep does the relationship between our spatial experiences and social worlds really go? Is there really a neural substrate that links our experiences of mountains and families or cities and colleagues?

If we describe someone as ‘distant’, we think of them in that spatial term, even if they’re next to us

At the start of this century, cognitive scientists began charting the psychological geometries of social space using carefully controlled experiments. These experiments asked whether the ‘distances’ we apply to other people in our imagined social worlds – thinking of a friend as close or of an acquaintance as distant – manifest in our behaviour toward those people. In one study, participants were asked to draw the route they would take to deliver a package along an S-shaped path that passed by three figures. The three figures were described as ‘friends’ to one group and ‘strangers’ to another. Participants in the ‘friends’ group drew lines along the path that were significantly closer to the figures compared with the lines drawn by participants in the ‘strangers’ group. The researchers reasoned that the effect was due to implicit associations between spatial proximity and friendship: distance was associated with strangers; closeness with friends.

In another study, Americans who held negative opinions about Mexico overestimated the distance between American and Mexican cities compared with Americans who held more positive views of Mexico. The authors of this study reasoned that distance estimations in the physical world were affected by how participants positioned Mexico in an imagined social space.

The spatial metaphors we use to describe social relations aren’t just idiosyncratic uses of language, but reflections of how those social relations are structured in our minds. When we describe someone as ‘distant’ or ‘out of touch’, we really think of them in those spatial terms, even if they are standing next to us.

To navigate the world, we rely on mental representations of where things are and how to interact with them. This is similar to the way that social information is conceptually represented: knowing where people are located in terms of affiliation and power is central to social functioning and helps us navigate our daily interactions. For cognitive neuroscientists, both operations share a similar phenomenology because we subjectively experience both ‘mapping’ tasks in similar ways. That is why mapping social content in a mental ‘space’ feels as intuitive as the mapping involved in geographic or architectural work.

However, it is not just that we use spatial experiences to make sense of social relationships. These effects also work in the other direction. We seem to process social content differently based on where it is located in the world. In one study, participants were shown pairs of ‘high’ and ‘low’ power words, such as ‘master’ and ‘servant’, on a screen. Through different exercises, the vertical positions of these words were altered so that each had a chance to appear above and below the other. The study found that participants recognised high-power nouns, like ‘master’, more quickly than low-power nouns, like ‘servant’, when they appeared above but not when they appeared below. Another study placed the words ‘friend’ and ‘enemy’ in different locations – near and far – on a 3D graphic, and found that the word ‘friend’ was recognised faster than the word ‘enemy’ when placed closer, while the word ‘enemy’ was recognised faster when it was placed far away. In both studies, researchers reasoned that the recognition of certain socially charged words improved when located in positions congruent with participants’ spatial representations of those social concepts. This allowed participants to process the words more rapidly.

There is a common cortical basis for spatial cognition and social cognition

Based on this evidence of a strong relationship between spatial and social cognition, you may assume that Gallese and Lakoff’s prediction was correct: there really are shared neural substrates for both types of thought. The research of cognitive neuroscientists seems to support this prediction. In one study from 2014, researchers tracked the brain activity of participants who were shown images of objects in different locations on a table. Participants were asked to judge whether an object was ‘closer’ or ‘farther’ from another object depicted in each image. Researchers recorded brain activity during these judgments and trained a machine-learning algorithm to decode and classify the data associated with both near and far distance judgments. Eventually, the algorithm could reliably determine whether the participant was making a near or far distance judgment just by analysing their brain activity.

Next, participants were asked to provide photographs of eight people in their social circles: four people they had a strong relationship with, and four people whom they knew but were not close to. Researchers measured the brain activity of participants while asking whether the person shown in each photograph was a ‘friend’ or ‘acquaintance’. The researchers referred to this task as the ‘social distance’ judgment task.

Instead of looking for overlap in brain activity between the two tasks, researchers used the trained algorithm from the spatial distance task to decode the data from the social distance task. The spatial algorithm was able, with above-chance accuracy, to predict participants’ responses to the social distance task. In other words, brain activity in one part of the brain associated with ‘near’ and ‘far’ spatial distance judgments – in this case, the inferior parietal lobule – could be used as a template to predict social distance judgments. This finding supports the claim that there is a common cortical basis for spatial cognition and social cognition. That friend who is ‘close’ to you, even if they live on the other side of the world, is being mapped by the same part of the brain that has determined you are ‘close’ to the screen you are using to read this essay.

So, what are the explanations of this? Some researchers argue that social cognition is an ‘exaptation’ of spatial cognition. An exaptation is a secondary use for an original adaptation. The most famous example of exaptation, first proposed by Charles Darwin, are the lungs found in all air-breathing animals. Rather than suggesting this organ evolved to intake oxygen, Darwin believed the lungs ‘exapted’ from the internal swim bladders of fish – a gas-filled organ that allows fish to control their buoyancy underwater. In the case of social cognition, some neuroscientists have argued that the neural systems for spatial cognition were ‘upcycled’ to form the basis of social cognition. This allowed social information to be organised in an orderly, dimensional manner, where individuals can be represented as coordinates in a topographical ‘space’ from which inferences can be generated, similar to how spatial information is represented.

Exaptation is a more parsimonious explanation for the development of two distinct but highly related brain functions, in comparison with an evolutionary explanation that suggests the independent development of two completely modular brain areas. If social and spatial cognition are truly hardwired together in the brain, as this argument suggests, that would explain our ability to immediately infer someone’s social status by perceiving their spatial position in social settings. It’s a provocative argument, but one that requires more research to validate.

Jacobins sat on the left side of the king, while members of the Royalists sat to his right

Importantly, this argument does not claim that social cognition can be reduced to spatial cognition. Other research from social psychology has demonstrated that our mental representations of people are multimodal. They include emotional associations, declarative knowledge and episodic memories, among other content. But, at the very least, this argument offers a plausible explanation for how we first acquired, and how we still experience, one of the most fundamental aspects of human cognition: our thoughts about other people. The broader implications of this idea force us to consider more deeply how the spaces we design reflect our implicit spatial associations with different groups of people, including friends, family, communities, and societies. Moreover, given that the spatial world can profoundly alter our social cognition, could architecture and other forms of spatial design act as conceptual tools for constructing new forms of social thought?

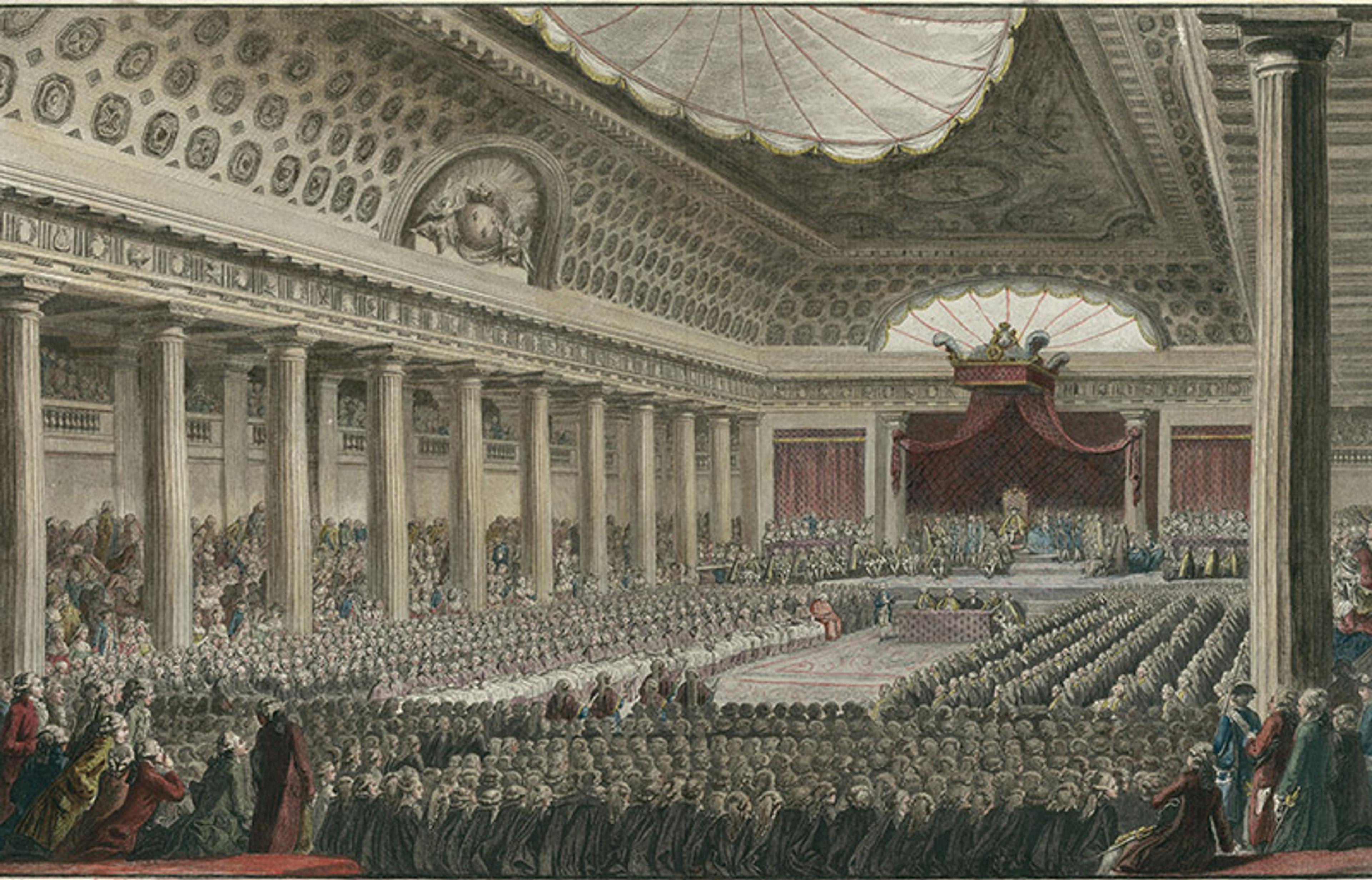

Opening of the Estates-General in Versailles 5 May 1789, engraving (1790) by Isidore Stanislas Helman. Courtesy Wikipedia

In fact, it has already happened. In May 1789, the three estates of French society – the clergy, nobility and commoners – gathered in Versailles to debate the levying of new taxes and to undertake reforms in the country. This event marked the turn towards democracy as the dominant system of political governance in France, as well as in much of the rest of Europe soon after. It was not only the ideas debated at this event that proved historic, but also the arrangement of those ideas in space.

In attendance were members of the Jacobin party, the anti-royalists who campaigned to abolish the monarchy and implement liberal policies. It just so happened that they sat on the left side of the king, while members of the Royalists, the party that wanted to conserve the monarchy and its power, sat to the king’s right. This seating arrangement stuck, and instead of referring to the names of either party, a spatial metaphor – ‘left’ and ‘right’ – could be used to distinguish between the two groups. Jacobins, the group that advocated for liberal policies, were on the ‘Left’; Royalists, those that advocated for conservative policies, on the ‘Right’.

This spatialisation of political groups endures today, even though the seating arrangement in which it was founded is now mostly forgotten and certainly abandoned – political parties no longer seat themselves on either side of a monarch. The origin story of the Left-Right political spectrum demonstrates the role that organising different social groups in space can have on how those groups are represented mentally. The effect of this mental representation on subsequent political thought cannot be understated. Today, more than two centuries later, there is no political party, politician or even political idea that isn’t positioned somewhere along the Left-Right political spectrum. The fact that the spatial relationship that this spectrum is based upon was initially arbitrary makes it even more remarkable.

If an arbitrary spatial configuration of people in space could have such a profound impact on the structure of political thought, could we take more deliberate control of these effects? Architecture offers a multitude of possible spatial configurations. The spaces architects design for different people can be tall, wide, open, confined, with or without views – each is a proposition for social thought. This is why we put those who win athletic competitions on the highest podium, why bosses of organisations often occupy the largest offices on the uppermost floors of buildings; why the heads of families traditionally slept in the ‘master bedroom’ and ate at the head of the table. Across these cases, power is constituted by being above, in the centre, having more space (or a better view).

The ‘maternal arms of Mother Church’; the Piazza San Pietro in Rome. Courtesy Wikipedia

Architecture has often been used as a tool to communicate specific narratives about social relations and distributions of power. Monumental structures like the Pyramids of Giza, the Forbidden City in Beijing, the Parthenon in Athens, or the Arc de Triomphe in Paris manipulate height, distance, mass, volume and boundaries to reify otherwise abstract ideas about power. Take, for example, St Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. Built during the 16th and 17th centuries, it broke away from traditional architectural standards for Catholic churches by donating a significant amount of space to the public in the form of the Piazza San Pietro, which can host hundreds of thousands of worshippers at one time. Instead of a square, Piazza San Pietro was designed as an oval surrounded by an open-air colonnade four rows deep. In the words of its architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the piazza embraces visitors in the ‘braccia materne della Chiesa’ (the ‘maternal arms of Mother Church’). It had to do so. After all, St Peter’s Basilica was built during the Protestant Reformation, a time when the authority of the Catholic Church in Rome – which appeared so removed from the concerns of the public – was questioned by Protestant Reformers in northern Europe. In response, the Roman Catholic Church embarked on its own Counter-Reformation, which involved dissolving its own nepotistic and corrupt practices and turning its attention back toward the people, including through the architecture at the Vatican. The spatial design of the Piazza San Pietro allowed the Catholic Church to signal a new era of social transparency and openness.

The architectural metaphor of the ‘glass ceiling’ expresses the barriers often invisible to men

But one needs not be an architect to alter collective social thought. Even architectural or spatial metaphors can produce an effect. Advocates for social progress, whether they are fighting against inequality, oppression or an erosion of rights, often ground their social experiences in spatial metaphors as they defend those who are ‘marginalised’, ‘oppressed’ or ‘subjugated’. For this reason, social justice movements often feature metaphors of occupation and agency in space.

In 1929, one year after women had won the right to vote in Britain, Virginia Woolf used an architectural metaphor – A Room of One’s Own – as the title of her feminist essay arguing for women’s intellectual agency. The ‘room’ in question can be interpreted both literally and metaphorically. In literal terms, Woolf writes that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.’ Private spaces for writing or study would have been luxuries for many women in the early 20th century. But the title’s full import is best understood as a metaphor that expresses the right of women to uninterrupted and self-driven intellectual pursuits – an idea Woolf explores throughout her essay.

Today, feminists use the architectural metaphor of the ‘glass ceiling’ to express the barriers often invisible to men (hence ‘glass’) that women experience as they climb the corporate ladder. Similarly, members of the LGBTQ+ community are encouraged to ‘come out of the closet’ to become socially visible. More recently, at the 2020 George Floyd protests, the call-and-response cry ‘Whose streets? Our streets!’ was used to communicate the unmet right of racial minorities to feel safe in public spaces. Like Woolf’s title, these expressions can be interpreted literally, but their full effect is best understood metaphorically. As spatial metaphors, they help describe how minority groups experience and seek to overcome social barriers. Without these metaphors, it can be very difficult to express, for example, the feelings of social isolation and constraint that members of the LGBTQ+ community experience from hiding their gender identity or sexual orientation. Through spatial metaphor, non-group members can understand the feelings of social isolation and constraint of a life lived ‘in the closet’.

Even the Left-Right political spectrum, which seems to lead toward political extremism, can be reconstructed using novel spatial metaphors. Spatial metaphors like ‘partisan’, ‘polarised’ or ‘extremist’ are often used to describe individuals who hold the strongest political views. These spatial metaphors generate meaning by referencing positions along a horizontal line with poles extending in opposite directions. But what if, rather than a straight line, we positioned political opinions on a horseshoe?

First coined in 2002 by the French philosopher Jean-Pierre Faye, ‘horseshoe theory’ has been debated by political theorists since the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a treaty of non-aggression signed in 1939 between Hitler’s Nazi government and Stalin’s Communist Party. Since then, the theory has been used to explain, among other things, the fact that 12 per cent of people who voted for Bernie Sanders in the 2016 Democratic primaries voted for Donald Trump in the presidential election, arguably costing the ‘Left-leaning’ candidate, Hillary Clinton, the election. Another example is that politicians and pundits on both the far-Left and far-Right have advocated anti-interventionist positions regarding the war in Ukraine. But that’s not to say there aren’t massive ideological differences between far-Left and far-Right political positions. Like the simple binary of the Left-Right spectrum, political theorists have argued that horseshoe theory also overly simplifies the ideological landscape. What is clear, though, is that novel spatial metaphors offer alternative forms to what are otherwise restrictively linear forms of political thought.

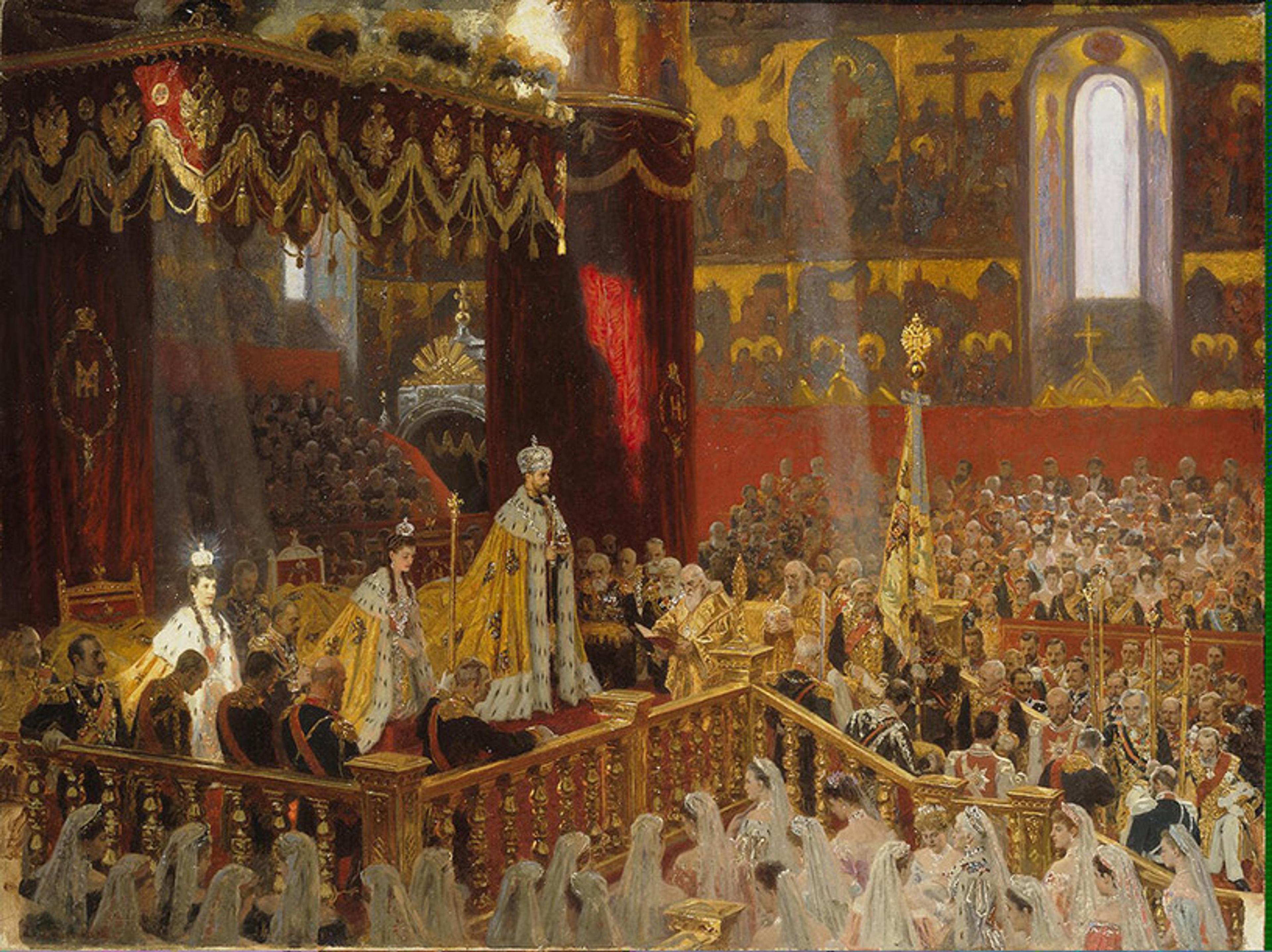

The possibilities of rethinking the shapes of social thought may seem vast. But spatial metaphors don’t always liberate. As is the case with a rigid conceptualisation of the Left-Right spectrum, sometimes they place constraints on social thought. The titles given to authority figures in our social and political institutions, such as ‘Headmaster’, ‘Your Highness’ or ‘Supreme Court’, often reference spatial conditions of height and mass. Even the title ‘President’ can be decomposed to a spatial metaphor: from the Latin praesident (‘sitting before’).

‘Highness’; The Coronation of Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (1898) by Laurits Tuxen. Hermitage Museum/Wikipedia

For this reason, it’s important to tune our ears to the spatial and architectural metaphors that may be constraining our interpersonal relations and political discourse. These metaphors can indicate growing mental divisions between social groups. Consider Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign and his rhetoric about building a wall along the southern US border. While some new border fencing was built during Trump’s presidency, the former president’s proposal to build an impenetrable wall is best understood as a metaphor that signalled a wider shift toward an isolationist stance in foreign policy and immigration.

Metaphorical barriers remain standing long after their physical referents are demolished

Similarly, for many people, the Great Wall of China marks a clear distinction between the Chinese nation to the south and marauding barbarians to the north. This idea endures, even if this literal wall has always been, in fact, a collection of many lesser walls – a porous physical reality that belies the monumentality of the metaphor. In Germany, citizens continue to overestimate distances between cities that were on the other side of what was the Iron Curtain, in comparison with cities on the same side before reunification. Further, these overestimations are greater for citizens with more negative attitudes toward reunification, compared with those of citizens who had positive views. Metaphorical barriers remain standing long after their physical referents are demolished.

For millennia, architects have designed buildings with spatial forms that far exceeded the functional needs of their occupants. Instead, they often sought to create structures that would be understood as metaphors for social power. Similarly, writers, activists and politicians have relied on spatial and architectural metaphors to communicate their social experiences and desires. Recent cognitive neuroscience research shows that there is a neurobiological basis for both effects.

This mechanism provides insight into the phenomenology, the subjectivity, of social experience, but it should also lead us to carefully consider what our movements and positions in space say about our social agency and status. Equally, it could lead to an understanding of how the architecture built for people in cities reflects the spatial distances implicitly attributed to them.

Insight isn’t all. There are also radical possibilities in social-spatial thought. Through this mechanism we can become architects of our collective experiences, building new metaphors for social life and shaping the geometries of other people in our minds.