Polycrisis. Metacrisis. Omnicrisis. Permacrisis. Call it what you like. We are immersed in an age of extreme turbulence and interconnected global threats. The system is starting to flicker – chronic droughts, melting glaciers, far-Right extremism, AI risk, bioweapons, rising food and energy prices, rampant viruses, cyberattacks.

The ultimate question hanging over us is whether these multiple crises will contribute to civilisational breakdown or whether humanity will successfully rise to such challenges and bend rather than break with the winds of change. It has been commonly argued – from Karl Marx to Milton Friedman to Steve Jobs – that it is precisely moments of crisis like these that provide opportunities for transformative change and innovation. Might it be possible to leverage the instability that appears to threaten us?

The problem is that so often crises fail to bring about fundamental system change, whether it is the 2008 financial crash or the wildfires and floods of the ongoing climate emergency. So in this essay, based on my latest book History for Tomorrow: Inspiration from the Past for the Future of Humanity (2024), I want to explore the conditions under which governments respond effectively to crises and undertake rapid and radical policy change. What would it take, for instance, for politicians to stop dithering and take the urgent action required to tackle global heating?

My motives stem from a palpable sense of frustration. Around two decades ago, when I first began to grasp the scale of the climate crisis, especially after reading Bill McKibben’s book The End of Nature (1989), I thought that, if there were just a sufficient number of climate disasters in a short space of time – like hurricanes hitting Shanghai and New York in the same week as the river Thames flooded central London – then we might wake up to the crisis. But in the intervening years I’ve come to realise I was mistaken: there are simply too many reasons for governments not to act, from the lobbying power of the fossil fuel industry to the pathological fear of abandoning the goal of everlasting GDP growth.

This sent me on a quest to search history for broad patterns of how crises bring about substantive change. What did I discover? That agile and transformative crisis responses have usually occurred in four contexts: war, disaster, revolution and disruption. Before delving into these – and offering a model of change I call the disruption nexus – it is important to clarify the meaning of ‘crisis’ itself.

Let’s get one thing straight from the outset: John F Kennedy was wrong when he said that the Chinese word for ‘crisis’ (wēijī, 危机) is composed of two characters meaning ‘danger’ and ‘opportunity’. The second character, jī (机), is actually closer to meaning ‘change point’ or ‘critical juncture’. This makes it similar to the English word ‘crisis’, which comes from the ancient Greek krisis, whose verb form, krino, meant to ‘choose’ or ‘decide’ at a critical moment. In the legal sphere, for example, a krisis was a crucial decision point when someone might be judged guilty or innocent.

The meaning and application of this concept has evolved over time. For Thomas Paine in the 18th century, a crisis was a threshold moment when a whole political order could be overturned and where a fundamental moral decision was required, such as whether or not to support the war for American independence. Karl Marx believed capitalism experienced inevitable crises, which could result in economic and political rupture. More recently, Malcolm Gladwell has popularised the idea of a ‘tipping point’ – a similar moment of rapid transformation or contagion in which a system undergoes large-scale change. In everyday language, we use the term ‘crisis’ to describe an instance of intense difficulty or danger in which there is an imperative to act, whether it is a crisis in a marriage or the planetary ecological crisis.

Overall, we can think of a crisis as an emergency situation requiring a bold decision to go in one direction rather than another. So what wisdom does history offer for helping us to understand what it takes for governments to act boldly – and effectively – in response to a crisis?

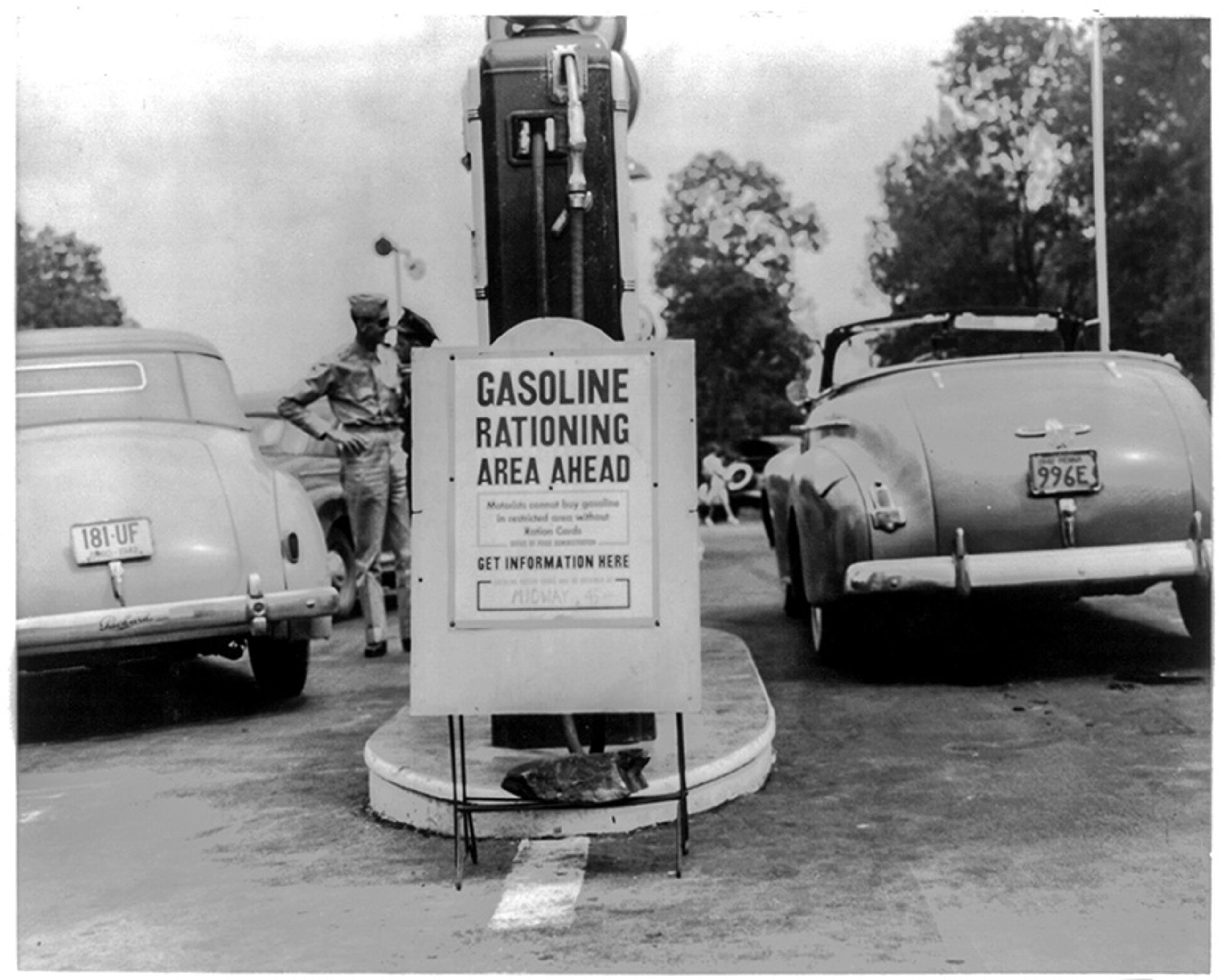

The most common context in which governments carry out transformative and effective crisis responses is during war. Consider the United States during the Second World War. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, the US government instigated a seismic economic restructuring to put the country on a war footing. Despite fierce opposition from industry, there was a ban on the manufacture of private cars, and petrol was rationed to three gallons per week. The president Franklin D Roosevelt increased the top rate of federal income tax to 94 per cent by the end of the war, while the government borrowed heavily and spent more between 1942 and 1945 than in the previous 150 years. And all of this state intervention was happening in the homeland of free market capitalism. Moreover, the wartime crisis prompted the US to throw the political rulebook out the window and enter a military alliance with its ideological arch enemy, the USSR, to defeat their common enemy.

Gasoline rationing on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, 1942. Courtesy the Library of Congress

A second context in which governments take radical crisis action is in the wake of disasters. Following devastating floods in 1953, which killed almost 2,000 people, the Dutch government embarked on building a remarkably ambitious flood-defence system called the Delta Works, whose cost was the equivalent of 20 per cent of GDP at the time. No government today is doing anything close to this in response to the climate crisis – not even in the Netherlands, where one-quarter of the country is below sea level and flooding has been a critical threat for centuries.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides another example. In response to the public health emergency, Britain’s ruling Conservative Party introduced a series of radical policy measures that would be generally considered inconceivable by a centre-Right government: they shut schools and businesses, closed the borders, banned sports events and air travel, poured billions into vaccination programmes and even paid the salaries of millions of people for more than a year. It was absolutely clear to them that this was a problem that markets would be unable to solve.

The reality is that the climate emergency is the wrong kind of crisis

A third category of rapid, transformative change is in the context of revolutions, which can generate upheavals that create dramatic openings in the political system. The Chinese Communist Party, for instance, introduced a radical land redistribution programme during the civil war in the late 1940s and following the revolution of 1949, confiscating agricultural property from wealthy landlords and putting it into the hands of millions of poor peasant farmers.

Similarly, the Cuban Revolution of 1959 provided an opportunity for Fidel Castro’s regime to launch the Cuban National Literacy Campaign. In early 1961, more than a quarter of a million volunteers were recruited – 100,000 under the age of 18, and more than half of them women – to teach 700,000 Cubans to read and write. It was one of the most successful mass education programmes in modern history: within a year, national illiteracy had been reduced from 24 per cent to just 4 per cent. Whatever your views on Castro’s Cuba, there is no doubt that revolutions can drive radical change.

These three contexts – war, disaster and revolution – help explain the overwhelming failure of governments to take sufficient action on a crisis such as climate change. The reality is that it is the wrong kind of crisis and doesn’t fit neatly into any of these three categories. It is not like a war, with a clearly identifiable external enemy. It is not taking place in the wake of a revolutionary moment that could inspire transformative action. And it doesn’t even resemble a crisis like the Dutch floods of 1953: in that case the government acted only after the disaster, having ignored years of warnings from water engineers (in fact, unrealised plans for the Delta Works already existed), whereas today we ideally need nations to act before more ecological disasters hit and we cross irreversible tipping points of change. Prevention rather than cure is the only safe option.

Does that mean there is little hope of governments taking urgent action in response to a crisis like the ecological emergency or other existential threats? Is human civilisation destined to break rather than successfully bend in the face of such critical challenges? Fortunately, there is a fourth crisis context that can jumpstart radical policy change: disruption.

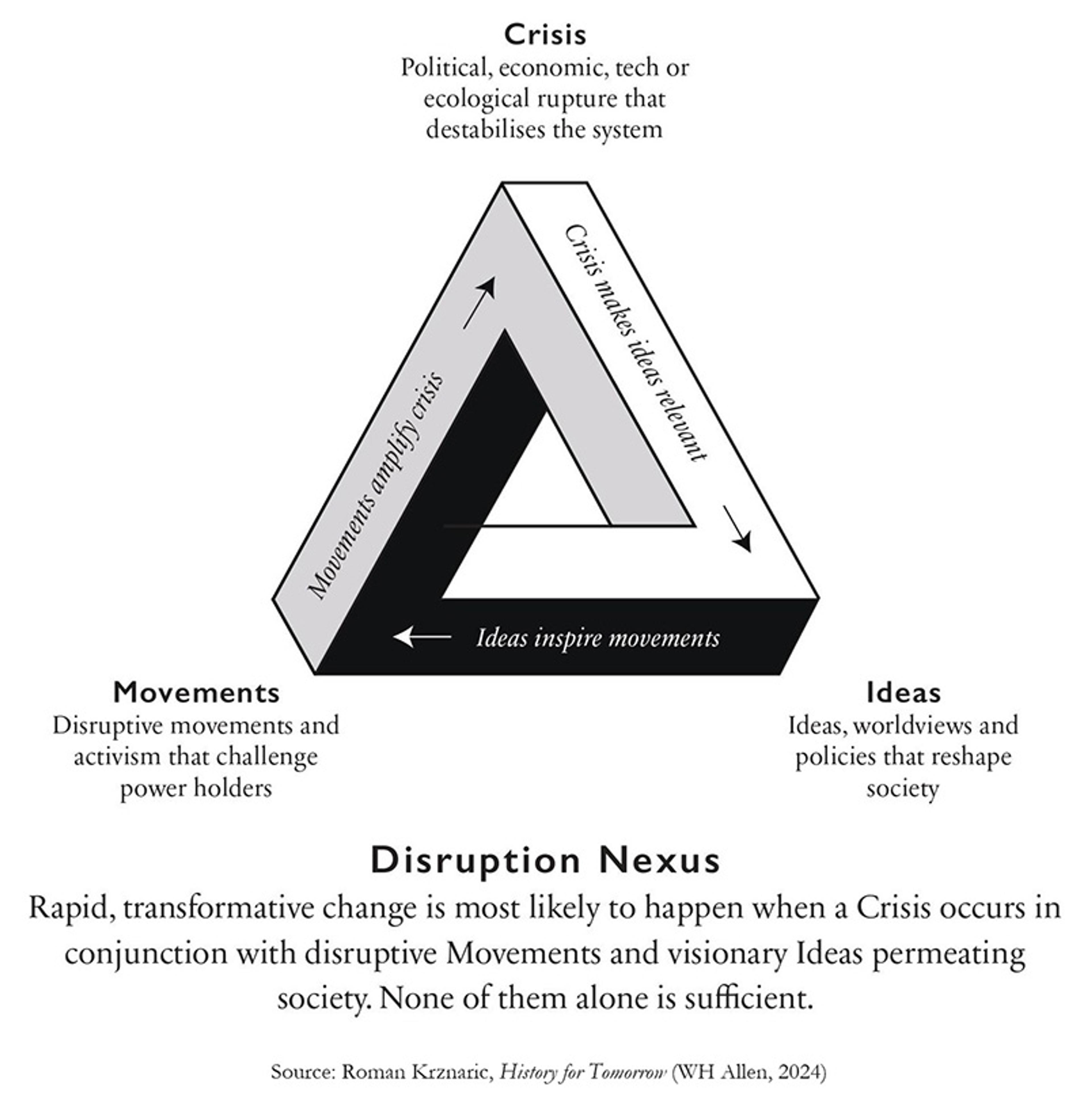

By ‘disruption’ I am referring to a moment of system instability that provides opportunities for rapid transformation, which is created by a combination or nexus of three interlinked factors: some kind of crisis (though typically not as extreme as a war, revolution or cataclysmic disaster), which combines with disruptive social movements and visionary ideas. These three elements are brought together in a model I have developed called the Disruption Nexus (see graphic). Here is how it works.

Let’s begin with the top corner of the triangular diagram labelled ‘crisis’. The model is based on a recognition that most crises – such as the 2008 financial meltdown or the recent droughts in Spain – are rarely in and of themselves sufficient to induce rapid and far-reaching policy change (unlike a war). Rather, the historical evidence suggests that a crisis is most likely to create substantive change if two other factors are simultaneously present: movements and ideas.

Public meetings and pamphlets were not enough to tip the balance against the powerful slave-owning lobby

Social movements play a fundamental role in processes of historical change. Typically, they do this through amplifying crises that may be quietly simmering under the surface or that are ignored by dominant actors in society. As Naomi Klein writes in her book This Changes Everything (2014):

Slavery wasn’t a crisis for British and American elites until abolitionism turned it into one. Racial discrimination wasn’t a crisis until the civil rights movement turned it into one. Sex discrimination wasn’t a crisis until feminism turned it into one. Apartheid wasn’t a crisis until the anti-apartheid movement turned it into one.

Her view – which I think is absolutely right – is that today’s global ecological movement needs to do exactly the same thing and actively generate a sense of crisis, so the political class recognises that ‘climate change is a crisis worthy of Marshall Plan levels of response’.

Multiple historical examples, which I have explored in detail in my book History for Tomorrow (and where you can find a full list of references), bear out this close relationship between disruptive movements and crisis.

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 in Britain provides a case in point. There was certainly a generalised sense of political crisis in the country in the early 1830s. Urban radicals were pressuring the government to widen the electoral franchise, and impoverished agricultural workers had risen up in the Captain Swing Riots. On top of this, antislavery activists were continuing their decades-long struggle: more than 700,000 people remained enslaved on British-owned sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Yet their largely reformist strategy – such as holding public meetings and distributing pamphlets – was still not enough to tip the balance against the powerful slave-owning lobby.

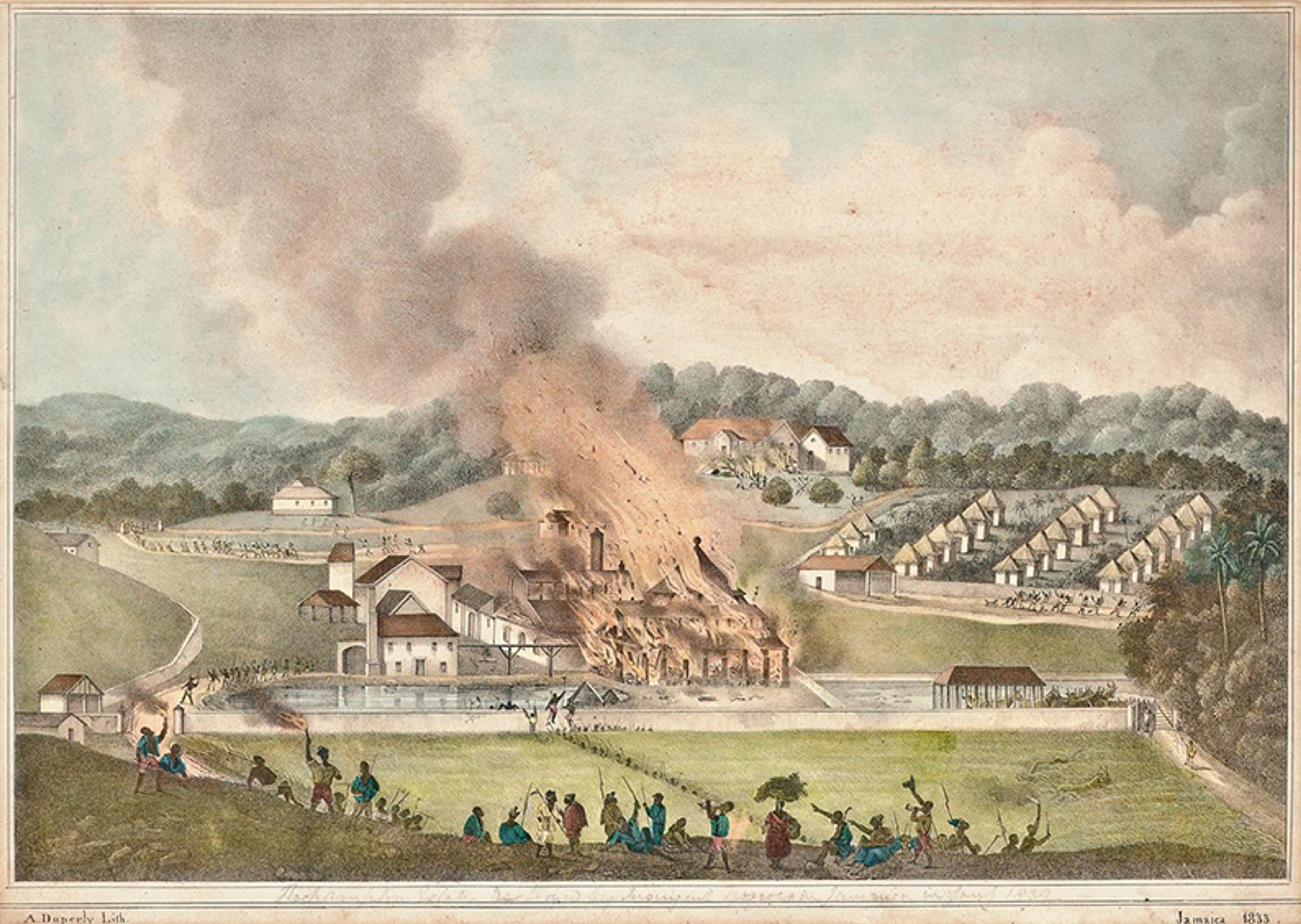

The turning point came in 1831 in an act of disruption and defiance that created shockwaves in Britain: the Jamaica slave revolt. More than 20,000 enslaved workers rose up in rebellion, setting fire to more than 200 plantations. The revolt was crushed but their actions sent a wave of panic through the British establishment, who concluded that if they did not grant emancipation then the colony could be lost. As the historian David Olusoga points out in Black and British (2016), the Jamaica rebellion was ‘the final factor that tipped the scales in favour of abolition’. In the absence of this disruptive movement, it might have taken decades longer for abolition to enter the statute books.

The Destruction of the Roehampton Estate (1832) by Adolphe Duperly, during the Jamaica rebellion. Courtesy Wikimedia

Another case concerns the granting of the vote to women in Finland in 1906. During the political crisis of the general strike of 1905 – an uprising against Russian imperialism in Finland – the Finnish women’s movement took advantage of the situation by taking to the streets along with trade unionists. The League of Working Women, part of the growing Social Democratic movement, staged more than 200 public protests for the right of all women to vote and run for office, mobilising tens of thousands of women in mass demonstrations. By magnifying the existing crisis, they were able to finally overcome the parliamentary opposition to female suffrage.

More recently, the mass popular uprisings in Berlin in November 1989 amplified the political crisis that had been brewing over previous months, with turmoil in the East German government and destabilising pro-democracy protests having taken place across the Eastern Bloc, partly fuelled by the reforms of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Their actions made history on 9 November when the Berlin Wall was finally breached and the system itself visibly came tumbling down.

In all the above cases, however, a third element alongside movements and crisis was required to bring about change: the presence of visionary ideas. In Capitalism and Freedom (1962), the economist Milton Friedman wrote that, while a crisis is an opportunity for change, ‘when that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around’. From a different perspective, Hannah Arendt argued that a crisis was a fruitful moment for questioning orthodoxies and established ideas as it brought about ‘the ruin of our categories of thought and standards of judgement’, such that ‘traditional verities seem no longer to apply’. Dominant old ideas are in a state of flux and uncertainty, and fresh ones are potentially ready to take their place. In these three historical examples, disruptive ideas around racial equality, women’s rights and democratic freedoms were vital inspiration for the success of transformational movements.

The 2008 financial crash illustrates what happens in the absence of unifying ideas. Two corners of the triangle were in place: the crisis of the crash itself and the Occupy Movement calling for change. What was missing, though, were the new economic ideas and models to challenge the failing system (exemplified by the Occupy slogan ‘Occupy Everything, Demand Nothing’). The result was that the traditional power brokers in the investment banks managed to get themselves bailed out and the old financial system remained intact. This would be less likely to happen today, when new economic models such as ‘doughnut economics’, degrowth and modern monetary theory have gained far more public prominence.

Is the disruption nexus a watertight theory of historical change? Absolutely not. There are no iron laws of history, no universal patterns that stand outside space and time. I’m a firm believer in the statistician George Box’s dictum that ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’.

Several caveats are worth noting. I’m certainly not claiming that transformative change will always take place if all three elements of the disruption nexus are in place: sometimes, the power of the existing system is simply too entrenched (that’s why US peace activists were unable to stop the Vietnam War in the late 1960s – although they certainly managed to turn large swathes of the public against it). My argument is rather that change is most likely when all three ingredients of the nexus are present.

Occasionally, crisis responses can come into conflict with one another, making it difficult to take effective action: in 2018, when the French government attempted to increase carbon taxes on fuel to reduce CO2 emissions, it was met with the gilets jaunes (yellow vest) movement, which argued that the taxes were unjust given the cost-of-living crisis that had been pushing up energy and food prices.

Furthermore, at times, other factors apart from disruptive movements or visionary ideas will come into play to help create change, such as the role of individual leadership. This was evident in the struggle against slavery, with important parts played by figures including Samuel Sharpe, Elizabeth Heyrick and Thomas Clarkson. The full story of abolition cannot be told without them.

The interplay of the three elements creates a surge of political will, that elusive ingredient of change

Finally, it is vital to recognise that crises can be taken in multiple directions. The Great Depression of the 1930s may have contributed to the rise of progressive Social Democratic welfare states in Scandinavia, but it equally aided the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy. When it comes to crises, be careful what you wish for. Those who desire an avalanche of crises to kickstart change are playing with fire.

Perhaps the greatest virtue of the disruption nexus model – in which movements amplify crisis, crisis makes ideas relevant, and ideas inspire movements – is that it provides a substantive role for collective human agency. During a wartime crisis, military and political leaders typically take charge. In contrast, a disruption nexus provides opportunities for everyday citizens to organise and take action that can potentially shift governments to a critical decision point – a krisis in the ancient Greek sense – where they feel compelled to respond to an increasingly turbulent situation with radical policy measures. The interplay of the three elements creates a surge of political will, that elusive ingredient of change.

History tells us that this is our greatest hope for the kind of green Marshall Plan that a crisis such as the planetary ecological emergency calls for. This is not a time for lukewarm reform or ‘proportionate responses’. ‘The crucial problems of our time no longer can be left to simmer on the low flame of gradualism,’ wrote the historian Howard Zinn in 1966. If we are to bend rather than break over the coming decades, we will need rebellious movements and system-changing ideas to coalesce with the environmental crisis into a Great Disruption that redirects humanity towards an ecological civilisation.

Will we rise to the challenge? Here it is useful to make a distinction between optimism and hope. We can think of optimism as a glass-half-full attitude that everything will be fine despite the evidence. I’m far from optimistic. As Peter Frankopan concludes in The Earth Transformed (2023): ‘Much of human history has been about the failure to understand or adapt to changing circumstances in the physical and natural world around us.’ That is why the great ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia and the Yucatán peninsula have disappeared.

On the other hand, I am a believer in radical hope, by which I mean recognising that the chances of success may be slim but still being driven to act by the values and vision you are rooted in. Time and again, humankind has risen up collectively, often against the odds, to tackle shared problems and overcome crises.

The challenge we face as a civilisation is to draw on history for tomorrow, and turn radical hope into action.