You’ve probably looked at millions of images in your professional life, and you’ve taken many, many thousands. What makes some of them stand out?

It’s not just photographs. You have to think why pictures stick, why we remember some of them so well, and others less well. Think of the Vermeer painting Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665): a portrait of a girl just looking round. Now, why, of the millions of portraits that have been made, is that one memorable? Why is the Mona Lisa (1506) memorable? Why are quite a lot of Van Gogh’s paintings so memorable: The Starry Night (1889), Sunflowers (1888), The Night Café (1888)? They just stick, and it’s possibly because they are haunting, that kind of green colour of The Night Café: there’s something that tickles the cognitive processes that allows us to remember it. So, quite clearly in the canon of the history of art, there are paintings, more or less the same ones for everyone, that we remember. Why is this?

Coming on to photography, there is the same phenomenon. What fascinates me is not photographs that have an obvious catastrophic history or story behind them, that would make them memorable because of the content, such as Grief (1942), Dmitry Baltermants’s photograph from the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula, of people searching for dead relatives among the corpses in Crimea. That is, of course, a memorable photograph, but to a large degree it’s because of the story. The same is true of the shocking photographs from Bergen-Belsen by George Rodger, which are memorable because of what they show.

But it’s the quiet, everyday, ordinary sort of little pictures that stick that fascinate me, the ones that are harder to explain. I can think of perhaps three or four: one by Alec Soth in his book Sleeping by the Mississippi (2008). It’s a photograph that just shows a painting on a wall – the wall is light blue and there’s a red chair in the picture, but it says almost everything about half-abandoned Midwestern houses; it’s somehow representative of the quiet, sleepy Midwest.

Photo by Alec Soth/Magnum

Similarly, quite a few of Walker Evans’s photographs have that power, much more power than the tougher, Dustbowl images from people such as Russell Lee. Suddenly, there’s this quiet church interior that is utterly memorable: it’s just a few pews, but you sense all the people who were there and then left. It’s also about the light, and the way we remember light. There’s another photograph I think of, by Guy Tillim, from his book Avenue Patrice Lumumba (2009): just three typists in an office in the Congo, and what’s striking is that it’s not a decisive moment, but it’s something about their dignity, the fact that they are not somehow characterised; they are simply themselves, they carry with them their own force, their own agency.

Typists, DRC, 2009. Photo by Guy Tillim/Vu

Many photographs of Africans are interpretations of what we’ve read. We have those photographs of women working, carrying water for example, and most of the photographs of women in Africa are characterisations of the way women are described in representations of Africa. We have very few photographs of female African intellectuals working, talking, thinking, reading. If I saw a photograph of an African woman reading, that would become memorable because it would step outside of the representational trope of the working African woman. I suppose the photograph that’s memorable, at one level, has to be somehow surprising.

Of course, it could be that there are different things going on with different photographs, so some are memorable because they’ve got a particularly pleasing geometrical aspect or, as you mentioned, in one the use of colour could somehow stimulate certain neurological reactions. Or there might be something that is archetypal, like a relationship between a child and a mother that somehow triggers emotion at a deep level. Perhaps there just isn’t a common denominator to all the images that stick with us?

That’s very true. Often, for me, the most memorable images are ones that break a mold, or break a silence. You talk about a mother and child, and I think of Adriana Lestido’s book Madres e Hijas (1995-99): it’s extraordinary because, throughout the history of photography, we are used to a maternal mother looking after the poor children. A madonna character is another archetypal theme throughout the history of photography. You can go all the way back to Julia Margaret Cameron and forward through Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936) thinking in those terms, and then we have Lestido breaking that mold with her book on mothers and daughters. She recognised that the supportive relationship went two ways, and she has very powerful pictures of daughters comforting their mothers in the book. I remember two photographs in particular because they break that trope, because they’re surprising, and I will never forget them for that reason.

Eugenia and Violeta, Argentina, 1998 by Adriana Lestido

Another memorable image is Don McCullin’s soldier in the Vietnam War with shellshock (1968). There must have been hundreds of thousands of images of soldiers taken during that war, yet that one has a special haunting quality.

There’s an interesting comparison between this photograph by McCullin and photographs by Gilles Caron. In the Caron photographs, the subject is almost always reflective, almost always the eyes are averted from the camera: somebody described Caron as continually photographing versions of Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (1904). What Caron was doing through most of his work – he died young, sadly – was projecting his own uncertainty about the war, his own reflections onto the subjects: he waited for the subject to adopt a particular pose.

With McCullin, by contrast, a lot of his photographs are quite frontal, both from Biafra, particularly the ones that were published in The Sunday Times in July 1969, and also many from Vietnam. There’s a frontality to his work, and a stillness. A lot of the photographs we saw of conflict at that time – I’m thinking of Horst P Horst’s work, the Associated Press work, a lot of Larry Burrows’s work – is about action: it’s about soldiers moving under fire, rescuing people, moving through space. What’s striking about McCullin’s photograph of the solider is its stillness, the fact that it isn’t moving at all, it’s almost anti-television in that sense, and it allows you to reflect upon the detail in the photograph: the soiled jacket buttoned up to the neck, the fact that the soldier’s rifle is dirty, his hands are dirty, his face is covered in dirt, he hasn’t been able to take care of himself, and these things are all somehow reflected in this frozen moment.

Photo by Don McCullin/ContactPress

We get the same kind of effect from Chris Killip’s photograph of an elderly metal worker in the North East of England in 1978. All we see is his overcoat and his shoes, and he’s sitting on a wall, so we don’t see his face at all, but it’s the incredible detail, almost every stitch in the coat becomes a mini history: it’s as if he’s repaired his coat many times. Photographs can hold and suggest extraordinary detail, and I think it’s that detail that becomes memorable.

For me, the most important part of the McCullin photograph is the one that’s most occluded: the solider’s eyes have this thousand-yard stare. McCullin has chosen to photograph them in such a way that they’re almost invisible because of the shadow from the soldier’s helmet.

Yes, you have to look for his eyes. There are different printings of the picture, but you go into the heart of darkness under that helmet, and there are these eyes, and they stare straight at you, and they’re incredibly haunting. You go into that and you stay there. It’s very hard, once you get to those eyes, to leave them, and you feel the cold, and that stillness and also, I suppose, by extension, we feel ‘the madness of war’, a phrase McCullin used to label the image in his book Sleeping with Ghosts (1994).

Is the point of photography, serious photography, to find or create memorable images?

That’s a very good question. Some photographers, for example Josef Koudelka, are completely in tune with the larger picture of their life’s work, of what they’re doing, and they understand where they’re trying to get to every time they go out with a camera. Other photographers get close to that ‘state of grace’, as Sergio Larrain called it, only occasionally. When Larrain was working on his book Valparaiso (1963), and photographed that memorable image of two girls going down some steps, mirrored, with their short hair, he wrote that he’d reached this kind of ‘state of grace’. It’s a special kind of knowing, feeling that you have what you’re looking for without really understanding what it is that you’re looking for.

Passage Bavestrello, Valparaiso, Chile, 1952. Photo by Sergio Larrain/Magnum

To answer your question more precisely, it’s about being in tune with a much larger picture of a life or a life’s work, and that’s what made, say, Van Gogh as a painter so great – his career lasted only 10 years, 11 at the most, but for every moment of that period he was utterly in tune with what he was saying with paint. It’s very hard to manage that as a photographer, though perhaps the discussion about managing it hasn’t been had. People aren’t sure when they hit or miss, or why they hit or miss.

I had a discussion about this recently with Soth who compared it to pop. There’s lots of music being produced, numerous good songs, even by the same artists, but why does everybody go back to, for example, Joan Armatrading’s Love and Affection (1976)? Why does everyone go back to particular pieces of music, even particular lines in a song? There’s a certain sort of transcendence that good art, good literature, has – a capacity to go beyond the ordinary and to become somehow extraordinary, and float meaningfully in the mind. There’s an upwelling of emotion that goes into the creation of good art and good photography, and it’s really the way that upwelling translates onto the flat, two-dimensional space of the picture that people pick up on and feel. It might be a very, very quiet moment, an unprepossessing sort of a photograph; and yet, for that reason, it’s even more forceful.

In documentary photography, people have emphasised the need to provide visual evidence of things that have happened, but some of the things you’re saying apply just as much to documentary photography as to photography that is less concerned with the truth. Even within documentary photography, the images that we value often don’t actually provide much legible evidence, though they typically do achieve what you’re talking about, this kind of memorable encapsulation of a moment, of a scene.

Yes. Documentary photography is an incredibly broad term, particularly if we go back to John Grierson’s concept of the creative treatment of actuality. It’s enormously broad. When I asked an art historian in Spain recently what the limits were, she just laughed and said: ‘I didn’t say there were any.’ There is a branch of documentary photography that is specifically evidence-based, and we see that from people who have been to Rwanda and Bosnia, looked at mass graves, put together evidence, or even going back to Susan Meiselas’s work in Nicaragua when she first arrived, gathering evidence of the death squads, and so on.

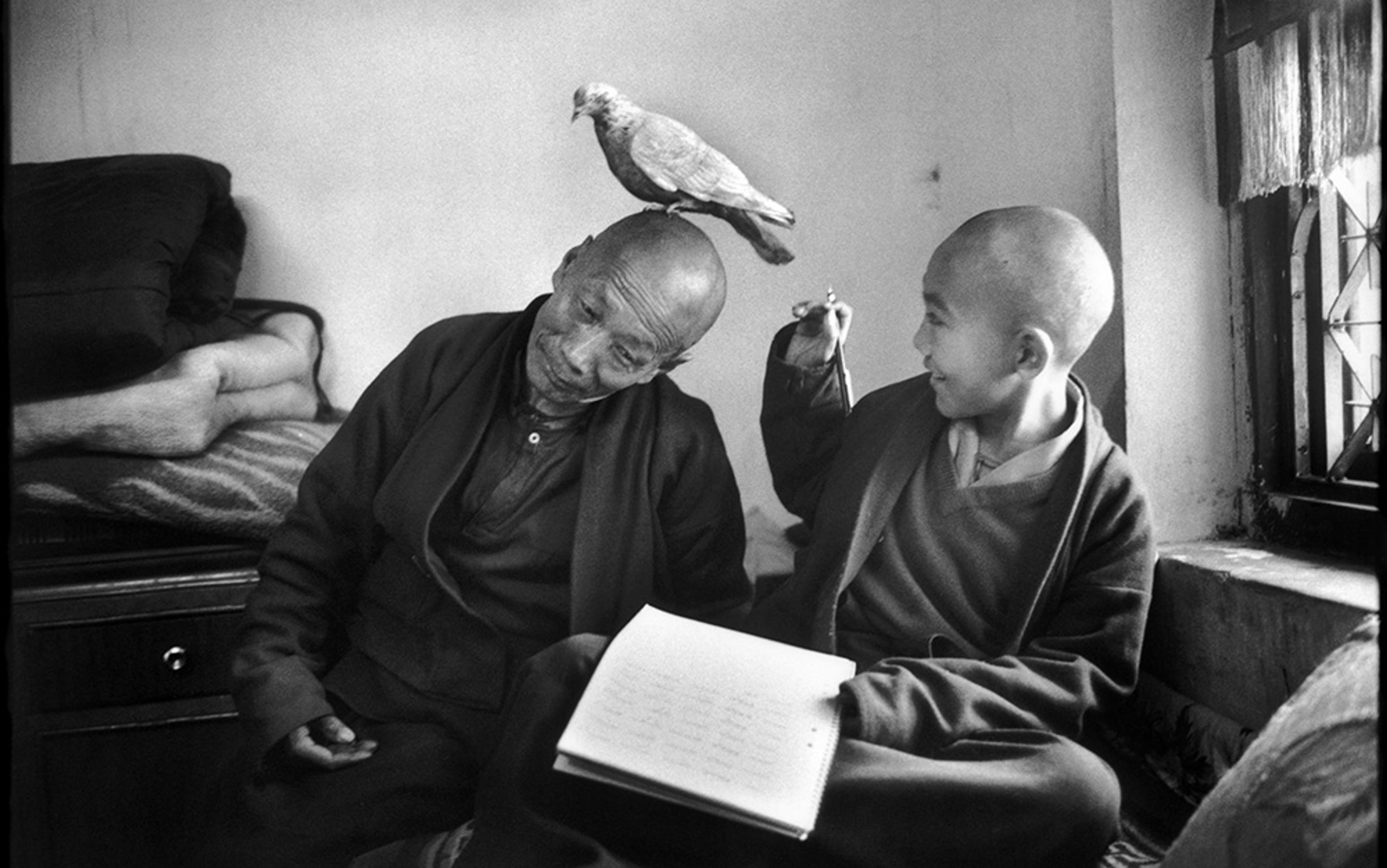

But documentary photography is a much bigger project than this, too. It’s about the way we represent ourselves, our life and everyone else’s and, in a sense, there aren’t limits to it. What distinguishes documentary from certain types of commercial photography is that it’s not trying to sell you anything. It’s not trying to sell you a house or a pair of cufflinks, it’s about trying to honestly tell the story of the world around us. That’s what sets documentary apart from all the other photography in the broadest sense. When I take a photograph of a road in Scotland, as a documentary photographer, I’m not trying to sell you that fence. What I’m trying to do is deliver a feeling of what it’s like to be there, to live there on this small Hebridean island. I look at another picture – by Martine Franck, of two Buddhists, an old Buddhist monk and a young lad – and there’s a glorious moment of a pigeon landing on the old monk’s head: a moment of joy and delight, and it’s got a quality that describes, in a sense, something more than it shows. It’s a small detail, but it reaches out to the bigger world of Buddhist life.

Khentrul Lodro Rabsel (12yrs old) with his tutor Lhaygyel, Shechen Monastery, Bodnath, Nepal. 1996. Photo by Martine Franck/Magnum

All successful documentary photography tries to make this transition from the particular to something more general, something more generally understood and more generally appreciated.

Whether you like it or not, the most memorable of your photographs is the Tiananmen Square picture Tank Man (1989). Is that frustrating, that this one has, through its content, through the moment it captured, become the most memorable from your work?

No, not at all. The photograph works and lives on on many different levels. It’s emblematic of the 1989 uprising in China; but also, it’s emblematic of a David-and-Goliath moment. Yet there are issues with the photograph, in fact with all iconic photographs: they have a tendency to erase the harsher realities that lie behind them. We saw this with the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima where, of course, we know nothing of the catastrophic battle that happened on that island. Similarly, the migrant mother in the Dustbowl hides the realities for many people, not just in the countryside but also in the cities during the Depression. We’ve got an enormous body of work from the countryside in the 1930s, but very little from the devastating experiences that people in the cities were going through.

Tiananmen Square is much the same in that, yes, it tells the story of a man in front of a tank. It became important because of television coverage. I think it was on 5 June 1989. It was seen by George Bush Snr, when he was in Kennebunkport in Maine, and he said: ‘Seeing the tank driver exercise restraint, I’m convinced that the forces of democracy are going to overcome these unfortunate events in Tiananmen Square.’ Well, of course, that was very important to Bush, he wanted to continue business as usual with the Chinese and, in fact, very shortly afterwards, he sent a secret trade mission, led by [his national security adviser] Brent Scowcroft, to Beijing. So the attention that the photograph generated had enormous political advantage for Bush, and also the Chinese government, who could say: ‘Look, the tank driver didn’t run him over.’ But at another level, of course, it became a poster on every student’s wall all over Europe as it showed the young Chinese man facing up to the juggernaut of the state. So it’s an oddly conflicted photograph, capable of being interpreted very differently.

Is there a risk that when we all carry sophisticated cameras on our phones, and take images very easily, that we lose sight of the fact that some images stick and some don’t? There are so many images that we forget the importance of the particular still moment, the poetic fixed photograph, the kind of memorable image that you’ve been talking about.

It’s about being tuned in. You could say the same for writing. There are millions of blogs and tweets on social media; you could ask: has the power of eloquence been reduced overall by that process? Have we lost our eloquence, our ability to describe, in a meaningful way, an experience? I don’t think so. People have always written letters, have taken photographs, millions of them, usually just for their own private memories. It doesn’t really matter for a lot of people, to what extent a photograph is eloquent, or well-composed, or resonant, because it’s just their granddaughter, or niece, or cat, or whatever, and it’s really a picture from that day, and therefore the immediate response is to put the figure of relevance or importance into the centre of the frame and that’s it. That’s good enough for them.

But if people want to speak to a wider audience and to produce photographs that other people want to put on their walls, a higher level of sophistication is needed. It’s like music: if you want somebody to go and listen to you or buy your song, there’s quite a level of sophistication that goes into producing that. It’s not like me singing in the bath. For great photography, a level of depth is necessary, but also an openness to interpretation. Memorable photographs have this quality of openness. They don’t bring closure, necessarily, to the moment or internally, they allow viewers to bring their their own thoughts to bear.

Interview by Nigel Warburton