Between 1890 and 1978, at Kamloops Indian Residential School in the Canadian province of British Columbia, thousands of Indigenous children were taught to ‘forget’. Separated from their families, these children were compelled to forget their languages, their identities and their cultures. Through separation and forgetting, settler governments and teachers believed they were not only helping Indigenous children, but the nation itself. Canada would make progress, settlers hoped, if Indigenous children could just be made more like white people.

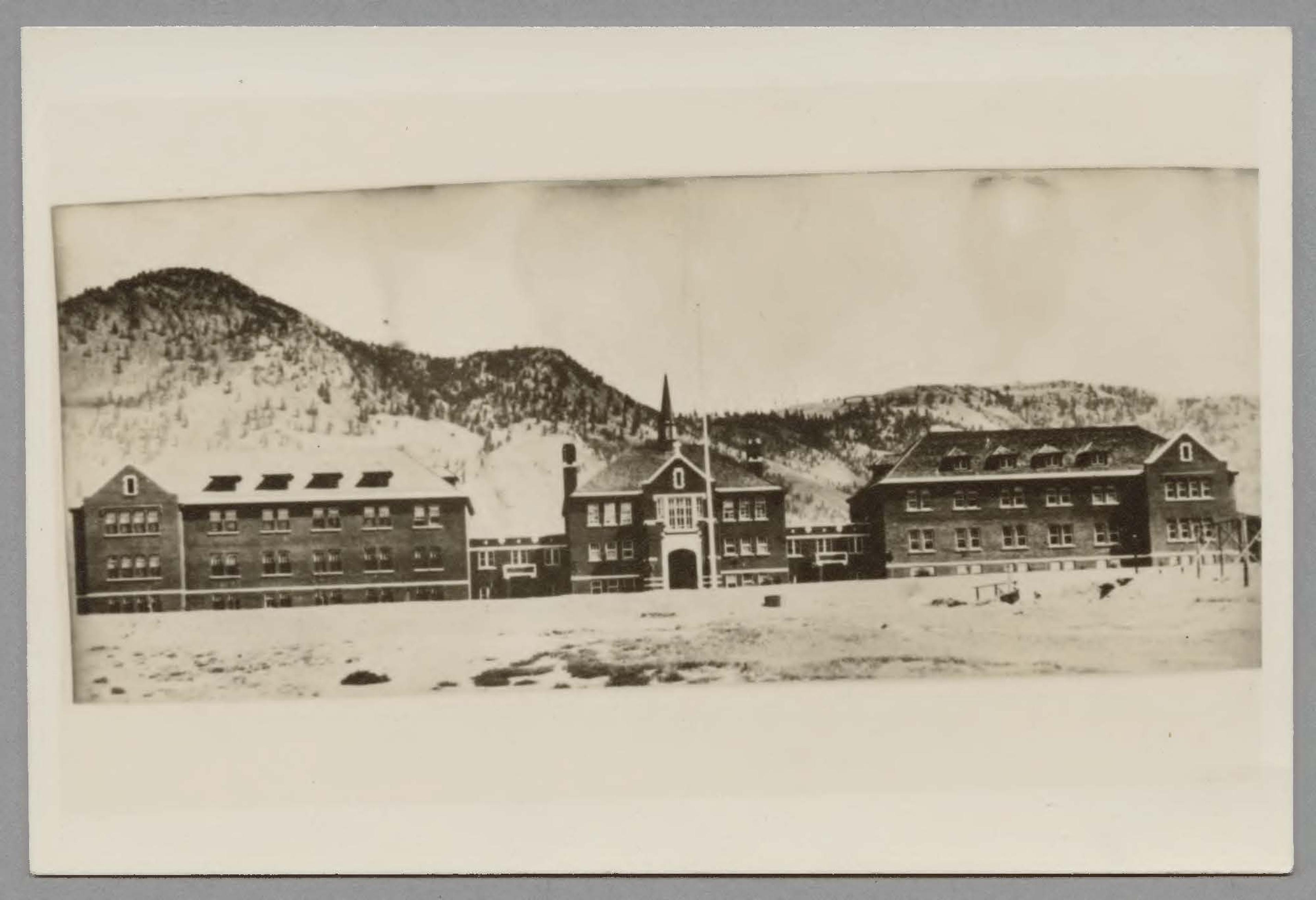

In 1890, this curriculum of forgetting was forcibly taught in the few wooden classrooms and living quarters that comprised Kamloops Indian Residential School. But in the early 20th century, the institution expanded, and a complex of redbrick buildings was constructed to accommodate an increase in students. In every year of the 1950s, the total enrolment at the ‘school’ exceeded 500 Indigenous children, making this the largest institution of its kind in Canada.

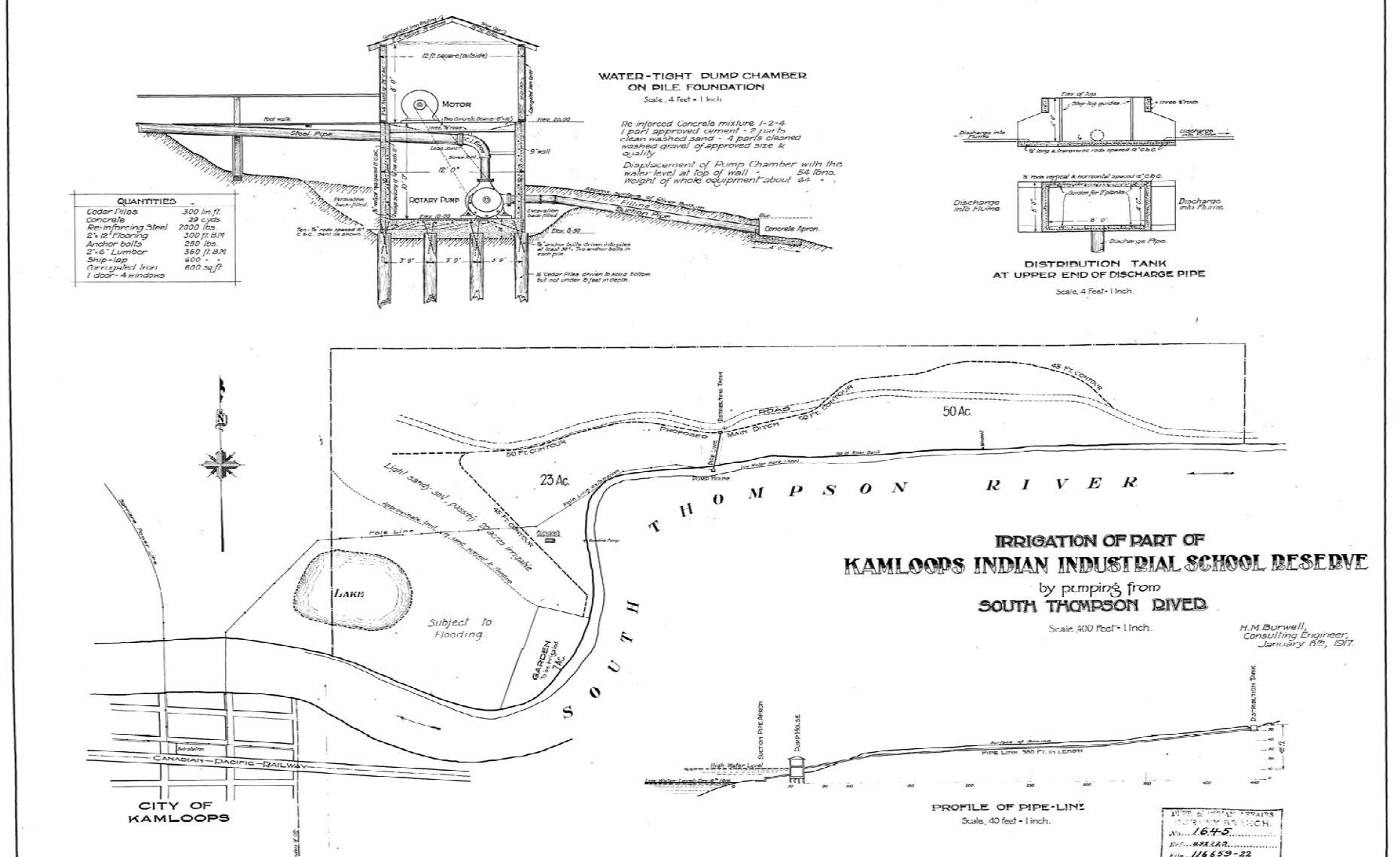

Plan of Kamloops Indian Residential School, 1917

View of Kamloops Indian Residential School, date unknown

Today, the redbrick buildings are still standing on the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation’s land. You can still look through the glass windows and see the old classrooms and halls. You can walk the grounds, toward the site of the former orchard or the banks of the nearby river. And you can stand over the graves of 215 children who died right here, at Kamloops Indian Residential School. Some never saw their fourth birthday.

You might think the Kamloops ‘school’ and its unmarked graves are an isolated and regrettable part of Canadian history, which we have now moved beyond. But that is a lie. Those 215 graves are part of a much larger political project that continues to this day.

When the burial sites at Kamloops were identified in May 2021 using ground-penetrating radar, news of the ‘discovery’ spread through international media. First-hand accounts of former students and Indigenous community members began to spread, too, and it soon became clear to the wider world that the ‘discovery’ was really a confirmation of what Indigenous peoples in Canada had known for generations. As Rosanne Casimir, the current Kúkpi7 (chief) of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, explains it, the search for bodies was a deliberate attempt to verify a knowing:

We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify. To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths … Some were as young as three years old. We sought out a way to confirm that knowing out of deepest respect and love for those lost children and their families, understanding that Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc is the final resting place of these children.

The testimonies from survivors and their descendants were met with expressions of shock and disbelief from settler Canadians: how could this have happened? Why didn’t we know anything about this? But the knowledge was no secret. It was publicly available in institutional records; it was in the testimonies of Indigenous peoples; and it was in 20th-century reports made by government officials. We didn’t just choose to forget, we participated in a grand project of forgetting.

Evelyn Camille, 82, a survivor of Kamloops Indian Residential School, beside a memorial to the 215 children whose remains were discovered there; 4 June 2021. Photo by Cole Burston/AFP/Getty

During the past decade or so, I have been finding out what I can – as a white British psychologist with longstanding interests in education and social justice – about this forgetting and the attempts made to forcibly assimilate Indigenous peoples through residential ‘schooling’. I am grateful beyond measure to the Indigenous peoples from Canada and elsewhere who have generously shared their experiences and stories with me over the years. Very often, their parting advice to me has been something along the lines of: ‘You should educate your own people about this.’ This essay is my most recent attempt to do so.

Abuses didn’t take place only in the dim and distant past

Yes, I’ve been honoured and privileged to have had Indigenous survivors of ‘educational’ systems, and their descendants, share their experiences and perspectives with me. But hearing the truth directly isn’t the only way for settlers and Europeans to learn and remember. The records are there, filled with the stories of those left to drown in the wake of settler colonisation. So, what does that say for our apparent ‘shock’? What does our ‘surprise’ really mean?

These questions become more confronting when we accept that abuses didn’t take place only in the dim and distant past. Consider this testimony from 1998 of Willie Sport who was a student, in the 1930s, of Alberni Indian Residential School in British Columbia:

… I spoke Indian in front of Reverend Pitts, the principal of the Alberni school. He said: ‘Were you speaking Indian?’ Before I could answer, he pulled down my pants and whipped my behind until he got tired. When I moved, he put my head between his knees and hit me harder. He used a thick conveyor belt, from a machine, to whip me.

That Principal Pitts was trying to kill us. He wouldn’t tell parents about their kids being sick and those kids would die, right there in the school. The plan was to kill all the Indians they could, so Pitts never told the families that their kids had tuberculosis.

I got sick with TB and Pitts never told anyone. I was getting weaker each day, and I would have died there with all those others but my Dad found out and took me away from that school. I would be dead today if he hadn’t come.

Abuses took place well into the 20th century. The revelation of the burial sites at Kamloops and the ensuing ‘shock’ of settler Canadians shows that forgetting – in the form of unlearning, concealment, or deception – is an integral part of the very system that killed those children and erased them from settler memories.

This forgetting is nothing new. It is part and parcel of the European colonial project. It enabled such endeavours as the ‘discovery’ and ‘claiming’ of territory, the physical slaughter of Indigenous populations, and the attempts to forcibly assimilate Indigenous peoples by interring their children in residential institutions. However, deception has also been used against European populations, too – the forgetting that accompanies forced assimilation goes both ways. When frameworks for dispossession become entrenched through educational, social and political systems, settler states can compel their citizenry to ‘forget’ the horrors of colonisation, to deny that these things ever happened, and to aggressively demand that others join them in this deliberately cultivated collective ‘amnesia’. Settler ‘forgetting’ isn’t just a lapse in memory. It inherits an older impulse: the intentional annihilation of Indigenous knowledge systems. It’s epistemicide.

For centuries, Indigenous peoples around the world have known that their children were taken away, that great harm was done to those children, and that their families and communities suffered. From the late 1800s to the late 1900s, roughly 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were interned in residential ‘schools’ in Canada. At almost the same time, Indigenous children around the world faced similar experiences, including Māori children in New Zealand; Aboriginal and Islander children in Australia and the Torres Strait Islands; Sámi, Inuit and Kven children in the Nordic countries; and Native children in the United States, among others. Many survivors have shared their memories of these experiences, and their lasting effects:

My soul was damaged. These are the most barren and fruitless of my learning years. They were wasted, so to speak, and a wasted childhood can never be made good.

– Anders Larsen, a Sámi teacher, reflecting on his days as a residential ‘school’ student in Norway in the 1870s

They just started using English, you could only – you could not use any other language … It’s like I had to be two people. I had to be Nowa Cumig, I had to be Dennis Banks. Nowa Cumig is my real name, my Ojibwa name. Dennis Banks had to be very protective of Nowa Cumig. And so I learned who the presidents were, and I learned the math, and I learned the social studies, and I learned the English. And Nowa Cumig was still there.

– Dennis Banks, leader in the American Indian Movement, describing his arrival at the Pipestone Indian Boarding School, Minnesota, in the 1940s, in the documentary series ‘We Shall Remain’ (2009)

I was sent out to work on a farm as a domestic … [I]t was a terrifying experience, the man of the house used to come into my room at night and force me to have sex … I went to the Matron and told her what happened. She washed my mouth out with soap and boxed my ears and told me that awful things would happen to me if I told any of the other kids … Then I had to go back to that farm to work … This time I was raped, bashed and slashed with a razor blade on both of my arms and legs because I would not stop struggling and screaming. The farmer and one of his workers raped me several times … I was examined by a doctor who told the Matron I was pregnant … My daughter was born [in 1962] at King Edward Memorial Hospital. I was so happy, I had a beautiful baby girl of my own who I could love and cherish and have with me always. But my dreams were soon crushed: the bastards took her from me and said she would be fostered out until I was old enough to look after her. They said when I left Sister Kate’s I could have my baby back. I couldn’t believe what was happening. My baby was taken away from me just as I was from my mother.

– Millicent D, an Aboriginal woman, describing her experiences at Sister Kate’s orphanage, Western Australia, in the 1960s, as part of the report ‘Bringing Them Home’ (1997)

‘Of one school on the reserve, 75 per cent were dead at the end of the 16 years since it opened’

Most Europeans and settlers have not attached any importance to first-hand Indigenous knowledge and experience because these accounts do not serve the colonial project. But some did pay attention, and they were horrified. As early as the 1920s, government officials in Canada and the US had raised serious concerns about the appalling conditions that existed in the ‘schools’ by faithfully (and statistically) documenting what they had observed. In a government report entitled The Story of a National Crime (1922), the Canadian physician Peter Bryce (who here refers to himself in the third person) noted that:

For each year up to 1914 he wrote an annual report on the health of the Indians, published in the Departmental report, and on instructions from the minister made in 1907 a special inspection of 35 Indian schools in the three prairie provinces. This report was published separately; but the recommendations contained in the report were never published and the public knows nothing of them. It contained a brief history of the origin of the Indian Schools, of the sanitary condition of the schools and statistics of the health of the pupils, during the 15 years of their existence. Regarding the health of the pupils, the report states that 24 per cent of all the pupils which had been in the schools were known to be dead, while of one school on the File Hills reserve, which gave a complete return to date, 75 per cent were dead at the end of the 16 years since the school opened.

The US statistician Lewis Meriam recorded similar concerns in a report titled ‘The Problem of Indian Administration’ (1928):

The survey staff finds itself obliged to say frankly and unequivocally that the provisions for the care of the Indian children in boarding schools are grossly inadequate … At the worst schools, the situation is serious in the extreme … The term ‘child labour’ is used advisedly. The labour of children as carried on in Indian boarding schools would, it is believed, constitute a violation of child labour laws in most states.

However, as Bryce noted, these reports were ignored or never published. When he attempted to publicise his findings, he was persecuted and forced into early retirement. Strategies of concealment and silencing continued. The last residential ‘schools’ for Indigenous children in North America only closed their doors between 1995 and 1998 – seven decades after the Bryce and Meriam reports.

What were the avowed purposes behind the global spread of Indigenous residential ‘schools’? And why was so much time, money and energy spent on building and operating these educational systems? One of the more direct explanations of the mindset that justified residential ‘schools’ appears in a speech given by Canada’s first prime minister, John A Macdonald, to the House of Commons in 1883:

When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.

Macdonald was repeating ideas that had become widespread and were uncontroversial at the time. These ideas were also echoed by Richard H Pratt, a US army captain who founded Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879 in Pennsylvania after ‘transforming’ 72 Indigenous prisoners of war who were in his charge. In 1892, Pratt gave a now-infamous summary of his educational philosophy:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one … In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.

The ‘kill the Indian, save the man’ dictum (as it became known) was positioned as philanthropic at the time because it seemed to mark a seemingly progressive transition from the policy of killing to ‘saving’ through educative assimilation. Pratt’s biographer described him as the ‘red man’s Moses’. But what is obvious in the words of both Macdonald and Pratt are the ideas that informed them: that the white man knows what is best for Indigenous children – better than their own families and communities – and what is best is assimilation, against which the ‘contaminating’ influences of family, culture and tradition must be held at bay. The intention was to play out these ideas until the very end. During a parliamentary committee in 1920, Canada’s Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, explained the state’s ultimate goal: ‘Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.’

Today, some might wonder why separating children from their families and cultures could have seemed like a good idea as recently as a century ago. We forget that these practices of separation and forgetting weren’t incidental, or historical accidents. Instead, they were deliberately positioned as progressive and philanthropic. And residential ‘schooling’ hasn’t been the only means by which these progressive and philanthropic practices of separation and re-education have been implemented. Forcible adoptions and ‘care’ systems – as in the ‘Stolen Generations’ in Australia and the ‘Sixties Scoop’ in Canada – show that those ‘progressive’ practices have continued and diversified. The fact that Indigenous children today are disproportionately highly represented in care systems worldwide suggests that these practices are still being implemented.

Peoples of colour were left in an intermediate position between Europeans and the animal world

The ideas that informed the Indigenous residential ‘school’ systems did not spring up in a vacuum. They are part of a longer history of Eurocentrism – whether informed by Christianity, Social Darwinism or today’s neoliberalism – in which peoples of colour are deemed to be ‘less than’ or ‘Other’. One of the sources of this way of thinking was the papal bull Inter caetera (1493), issued by Pope Alexander VI, which deemed non-Europeans as pagans whose souls would be damned without intervention from Christians. The Inter caetera explicitly allowed ‘full and free power, authority, and jurisdiction of every kind’ to colonising Europeans, effectively permitting the dispossession, enslavement and mass murder of Indigenous peoples. The papal bull is part of the so-called ‘doctrine of discovery’, a set of legal and religious precepts that certain European nations saw as giving them carte blanche to colonise the world. For many Indigenous people in Canada, the Pope’s 2022 apology for the abuses at the country’s residential ‘schools’ was meaningless without the Roman Catholic Church rescinding the doctrine of discovery. In an interview on CBC News in 2022, the Cree singer-songwriter, activist and educator Buffy Sainte-Marie said:

The apology is just the beginning, of course … The doctrine of discovery essentially says that it’s OK if you’re a [Christian] European explorer … to go anywhere in the world and either convert people and enslave, or you’ve got to kill them … Children were tortured.

In reconciliation efforts, the damaging legacy of the doctrine has rarely been acknowledged – and neither have other tools of colonisation, such as the electric chair used on Indigenous students at St Anne’s Indian Residential School in Ontario, Canada. As Saint-Marie said:

[The Canadian Museum for Human Rights] want my guitar strap and they want handwritten lyrics … happy, showy things. But I want them to put the damn electric chair right there and to actually show people the doggone doctrine of discovery.

In March 2023, following decades of pressure from Indigenous peoples, the Vatican issued an official statement formally repudiating the doctrine of discovery. Hailed by some as evidence of progress, the statement did not indicate that the doctrine had been (or would be) rescinded, and even suggested that the legacy of suffering ascribed to them was the result of misinterpretations and ‘errors’. Whether the Vatican’s statement constitutes, or could ever constitute, the type of rescindment that would be meaningful to Indigenous peoples is less than clear. The doctrine of discovery, however, weren’t the only pieces in the puzzle of ideas that informed the Indigenous residential ‘school’ systems.

As far as the colonial project went, the major practical result of the philosophical struggles between science and religion during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries was the partial replacement of theological dicta with a pseudoscientific justification of Eurocentric might and right that allowed Europeans to falsely biologise cultural, historical and economic differences. In the 19th-century European mind, most of the links of the medieval Christian ‘great chain of being’ were still very much intact. God and the angels might have been lopped off the top, but peoples of colour were left where they had always been, in an intermediate position between Europeans and the animal world.

In the settler states that emerged from European colonisation, governing powers attempted to create a sense of national security by positioning the emerging nation state – whether it was New Zealand, Australia, Canada or the US – as a single, unified people. The traditional motto that appears on the Great Seal of the United States, E pluribus unum (‘Out of many, one’), reflects the settler dream of a unified country. In the case of the US, this unification threatened to come apart during the Civil War in the early 1860s but was consolidated through the fantasy of ‘Manifest Destiny’ (the belief among settlers that, having reached the ‘promised land’, it was their duty to settle the continent from coast to coast). In reality, what ‘manifested’ was a long and bloody war with Indigenous populations for territory.

Following the physical slaughter, dispossession and subjugation of Indigenous populations around the world, survivors were to be assimilated. Education became the prime mover in these assimilative efforts with ‘school as the battlefield and teachers as frontline soldiers’, in the words of the Norwegian historian Einar Niemi. For Europeans in the late 1800s, notions of genetic determinism (stemming from Social Darwinism) began to be understood differently. A new idea was growing: though the ‘inferiority’ of Indigenous populations was probably ‘in the blood’, as scholars at the time believed, patterns of ‘savagery’ might be unlearned. Re-education was seen as the way to give younger generations their ‘best’ chance of living in the new society. You can almost hear the ‘progressive’ 19th-century Christian saying: Who knows, they might even become as good, civilised and enlightened – almost – as we white people.

Residential ‘schools’, like the one in Kamloops, relied on more than the informing ideas of Eurocentrism or Social Darwinism. They were also built on mechanisms of assimilative reform developed when new institutions – workhouses, reformatories and industrial schools – emerged in England (and other European nations) from the 1700s following the criminalisation of poverty and nomadism through the Poor Laws. The Canadian-born sociologist Erving Goffman considered them to be ‘total institutions’:

[A] social hybrid, part residential community, part formal organisation; therein lies its special sociological interest … In our society, they are the forcing houses for changing persons; each is a natural experiment on what can be done to the self.

What is ‘total’ in a total institution is the unidirectionality of power. This can be seen in psychiatric hospitals, leprosariums, nursing homes, orphanages, sanitaria or religious retreats, penitentiaries, prisons, poor houses, prisoner-of-war camps, or Indigenous residential ‘schools’. A 1994 report to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples – written by the Haudenosaunee activist, psychologist and professor Roland Chrisjohn, an expert on residential institutions in Canada, and his colleagues – described what these total institutions can do to the self:

Whether it was preparing prisoners for their eventual release into society, novitiates for service to a religious order, inductees to follow without question the orders of their superior officers, or victims of genocide to submit with minimal resistance to their destruction, the point of total institutions was the total war on the inner world … and the reconstitution of what was left along lines desired, or at least tolerated, by those in power.

Carceral archipelagos smoothed the way for philanthropic methods of reform to become techniques of ‘purification’

By their very nature, total institutions play up their roles as philanthropic sites of social good and reformation while playing down their role as sites where ‘enemy’ populations are confined, abused and sometimes murdered. In Europe, beginning around the 18th century, the hard line between helping and harming often dissolved as societal norms became institutionally enforced. Outsiders were seen as hostile to social progress. Europe’s ‘enemies’ included the psychiatrically ‘ill’, the intellectually and physically disabled, the children of the poor, women who were deemed sexually promiscuous (such as the ‘fallen women’ of Ireland), Indigenous populations around the world, religious minorities and any other disempowered ‘minorities’ who found themselves Othered by the state’s political and ideological whims.

The emergence of workhouses, reformatories and industrial schools as state-commissioned carceral archipelagos smoothed the way for philanthropic methods of reform to seamlessly become techniques of ‘purification’ and destruction. The ‘good work’ initiated and undertaken by powerful agencies in societies (often through total institutions) erases life-worlds, which extends the social power of these institutions far beyond their walls. And those of us who have been fortunate enough to remain on the outside of those walls are compelled towards a genuine or cultivated ignorance of what happens inside. We explain or rationalise the abuses that occur. We forget.

By the late 19th century, settlers wanting to address the ‘problem’ of Indigenous populations were armed with a surety of cultural superiority, a guiding principle of assimilation via education, and an institutional model. These tools seemed to elude any form of scrutiny. What could possibly go wrong?

On the inside of residential ‘schools’, the great chance being offered to (or more accurately, enforced upon) Indigenous children often didn’t look that great. Assimilation, as Pratt and others understood it, meant separating a child from their environment and erasing the ‘Indian’ inside them. Indigenous children were expressly forbidden to speak their own languages, wear their own clothes or jewellery, keep their hair long, keep their own names or, indeed, to express anything of their pre-institutional identities and cultures. In 2008, the NPR journalist Charla Bear reported on the experiences of Bill Wright, a Patwin elder, who was sent to the Stewart Indian School in Nevada in 1945, aged six:

Wright remembers matrons bathing him in kerosene and shaving his head … Wright said he lost not only his language, but also his American Indian name. ‘I remember coming home and my grandma asked me to talk Indian to her and I said: “Grandma, I don’t understand you,” Wright says. ‘She said: “Then who are you?” Wright says he told her his name was Billy. “Your name’s not Billy. Your name’s TAH-rrhum,” she told him. And [Wright] went: ‘That’s not what they told me.’

In the residential ‘schools’, physical abuse, often under the guise of castigations for the most minor of transgressions, could be extremely brutal. In 1995, Archie Frank told the Vancouver Sun what happened in 1938, when his friend and fellow Indigenous student Albert Gray, then aged 15, was caught stealing a prune at Ahousaht Indian Residential School in British Columbia:

The day after he got strapped so badly [by the school principal, Reverend Alfred E Caldwell] he couldn’t get out of bed. The strap wore through a half inch of his skin. His kidneys gave out. He couldn’t hold his water anymore … They wouldn’t bring him to a doctor. I don’t think they wanted to reveal the extent of his injuries.

Archie and another friend had tried to look after Albert by bringing him food, and changing his urine-soaked sheets but, after lying in bed for several weeks, Albert died. Reverend Caldwell was also accused of causing the death of a girl called Maisie Shaw in 1946, who died at Alberni Indian Residential School, after Caldwell had kicked her down a flight of stairs. He was also named as having sexually assaulted another girl, Harriet Nahanee, who was sexually abused by the school’s administrators for years. No charges were ever brought against him.

‘We owed our unspeakable boarding schools to the do-gooders, the white Indian-lovers’

Horrific sexual abuse in the ‘schools’ has been widely documented and seems to have been commonplace. In some institutions, the children became the involuntary subjects of medical experiments.

The goal of the ‘schools’ was a total transformation through re-education. This typically took place through labour training intended to prepare graduates for menial work. As the Sicangu Lakota activist and author Mary Crow Dog explains it in her book Lakota Woman (1990), those who graduated were trained to occupy the lowest occupational and social rungs in settler society:

Oddly enough, we owed our unspeakable boarding schools to the do-gooders, the white Indian-lovers. The schools were intended as an alternative to the outright extermination seriously advocated by generals Sherman and Sheridan, as well as by most settlers and prospectors over-running our land … ‘Just give us a chance to turn them into useful farmhands, labourers, and chambermaids who will break their backs for you at low wages.’

The system was, in the US historian David Wallace Adams’s words, an ‘education for extinction’. If those words seem strong, that’s only because we forget. As Bryce and Meriam documented in their (ignored) 1920s reports, hunger, disease and neglect were rife in residential institutions for Indigenous children. Death rates were horrific. In May 2015, the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Justice Murray Sinclair, estimated that at least 6,000 Indigenous children died while in the residential ‘school’ system, which would mean that the odds of dying were around the same for Indigenous children in residential ‘schools’ as for Canadian soldiers in the Second World War. However, conjectures of 6,000 may be a considerable underestimate. Coverage across CBC News in the months that followed the Kamloops recovery reported more than 1,300 potential unmarked burials at nine locations, and there were 139 Indigenous residential ‘schools’ in Canada. Furthermore, in those first five months, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation had documented 4,118 children who died in the residential ‘schools’, with less than a fifth of the records having been worked through.

For centuries, Indigenous peoples have had no option but to live with the consequences of assimilation via ‘education’. This includes abuse, separation (and ongoing disconnection) from family, the loss of cultural identity and language, intergenerational trauma, and a layered history of unresolved grief. Significantly, the ‘discovery’ of burial sites at Kamloops and elsewhere in Canada has coincided with the nation’s supposed engagement in processes of ‘truth and reconciliation’ with Indigenous populations.

Even in these endeavours, settler populations continue to privilege their own knowledge. The idea that settlers and Europeans have superior insights into the ‘best interests’ of Indigenous peoples has remained largely intact. Even attempts to apologise or seek ‘reconciliation’ are informed by a desire to draw a line and move on. Land return and Indigenous sovereignty are never on the table. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples delimits Indigenous ‘sovereignty’ to near-tokenism in its insistence on the preservation of the territorial integrity of nation states. Instead, what Indigenous peoples are being asked to reconcile with is loss, thus cementing the colonisation process.

In many truth and reconciliation processes, and in gestures of apology on the part of nation states, there seems to be an attempt to skip forward to reconciliation without taking the necessary interim steps of accountability and justice. Yet again, the wars we need to consider are not only the ones that have historically been fought against Indigenous bodies, but also the wars that continue to be waged on Indigenous and settler memories.

What is at stake in these wars is a specific kind of loss. It’s not only the suffering and deaths of Indigenous people, or the loss of land and language. It’s something more fundamental: genocide. Some Indigenous leaders in Canada felt that one of the most important outcomes of the papal visit in 2022 was the Pope’s subsequent recognition that what occurred was indeed, in his words, ‘genocide’. Following the papal visit, it became clear that the word ‘genocide’ apparently confuses many people.

How many people know that the Indigenous populations of the Americas declined by 90-98 per cent since 1492?

If one were to ask for an example of genocide, it is likely that most people would respond with the Shoah, the holocaust committed against Europe’s Jewish populations in the 1930s and ’40s. It is also likely that they would tell you that 6 million Jewish people died in the course of those atrocities, and that those 6 million comprised two-thirds or more of Europe’s Jewish population.

Today, there remain those who deny (sometimes publicly so) that such appalling actions ever took place. Repulsive in the extreme, this politically motivated historical revisionism has meant that, as of 2021, some 25 European countries as well as Israel have laws that address the phenomenon of Holocaust denial. But how many people know that the Indigenous populations of the Americas declined by between 90 and 98 per cent in the four centuries following the landing of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean in 1492? How many of them would know that the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide accurately describes the experiences of Indigenous peoples at the hands of European colonists and settlers? How many of them would know that the man who coined the word ‘genocide’, the Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, described the process as having ‘two phases; one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor’?

Following Lemkin’s description, all acts of settler colonisation should be understood as genocidal. But the sad reality is that using the term ‘genocide’ to refer to colonial and settler-colonial actions against Indigenous populations is still hotly disputed. Indeed, the New York Post marked the anniversary of the ‘discovery’ of the burial sites at Kamloops with an article in which participants in the project of forgetting were given free rein to ‘debunk’ the finding as the ‘biggest fake news story in Canada’.

Make no mistake, the wars on Indigenous and settler memories continue, and their perpetrators are finding new ways to wage them in the 21st century. This essay, too, will become part of that war. What would it mean to be on the right side of that war? For Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, an American historian and activist, and Jack Forbes, a Powhatan-Renapé and Delaware-Lenape historian, it means accepting a specific and necessary form of responsibility. Building on Forbes’s ideas, Dunbar-Ortiz writes:

[W]hile living persons are not responsible for what their ancestors did, they are responsible for the society they live in, which is a product of that past. Assuming this responsibility provides a means of survival and liberation.

Being on the right side of that war, and taking responsibility for the society we live in, demands finding a way out of the forgetting mindset. More than half a century ago, the Scottish psychiatrist R D Laing encapsulated much of what I think is at stake in his book The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise (1967):

It is not enough to destroy one’s own and other people’s experience. One must overlay this devastation by a false consciousness inured … to its own falsity.

Exploitation must not be seen as such. It must be seen as benevolence. Persecution preferably should not need to be invalidated as the figment of a paranoid imagination, it should be experienced as kindness … The colonists not only mystify the natives … they have to mystify themselves. We in Europe and North America are the colonists, and in order to sustain our amazing images of ourselves as God’s gift to the vast majority of the starving human species, we have to interiorise our violence upon ourselves and our children and to employ the rhetoric of morality to describe this process.

In order to rationalise our industrial-military complex, we have to destroy our capacity both to see clearly any more what is in front of, and to imagine what is beyond, our noses. Long before a thermonuclear war can come about, we have to lay waste our own sanity. We begin with the children. It is imperative to catch them in time. Without the most thorough and rapid brainwashing their dirty minds would see through our dirty tricks. Children are not yet fools, but we shall turn them into imbeciles like ourselves, with high IQs if possible.

Can we say that Laing’s observations do not ring true today? Through our genocidal and epistemicidal actions, we Europeans and settlers tried to ‘brainwash’ Indigenous peoples and their children, but those who survived saw through our ‘dirty tricks’, and despite our ‘educational’ systems, we failed to turn them into ‘imbeciles with high IQs’. Our epistemicidal actions have also produced successive generations of European and settler ‘imbeciles … with high IQs’, thus compounding the colonial project through self-mystification – we’ve brainwashed ourselves.

In my view, the burial sites at the residential ‘schools’ should force settlers and Europeans to question and challenge our cultivated amnesia, our continued obviation and obfuscation of truths and, above all, our ignorant and arrogant attempts to compel others to forget with us. But learning the facts is just the beginning. The Swedish author and journalist Sven Lindqvist stressed this point in the opening pages of Exterminate All the Brutes (1992), his exploration of colonisation and genocide:

You already know enough. So do I. It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.

If we cannot do this – if we cannot find the courage to face the truth – then surely we have abandoned, or lost forever, whatever tenuous claim we might have held towards progressive humanity. The burial sites of Indigenous children on the sites of residential ‘schools’ at Kamloops and elsewhere are some of the most recent reminders of the urgent, long-overdue necessity to do things differently.