Long before it entered the urban playgrounds of the 20th century, the swing was a ritual instrument of healing, punishment and transformation. Through repetitive, vertigo-inducing movements, the swing was used to celebrate gods and legendary beings, to ward off evil, alleviate suicidal impulses, heal mental illness, express sexual dominance or torment those accused of occult practices. But its deeper use has always been one of transformation: as it holds us in its oscillating spell, the swing calls into question the world we know, with its established hierarchies and rhythms. To swing is not only to play, but to open disorienting passages into transgressive spaces.

What does it mean to tell the story of this instrument? The history of the swing reveals how an object of disorientation became instrumentalised across the long arc of human culture, appearing in different territories and cultures throughout time. But this history is not just the story of an object. It’s also one of many untold histories of bodies in motion that seek to unveil forgotten, overlooked or concealed gestures – human history is not only populated with words and objects. The swing allows us to begin telling the long cultural story of moving back and forth through time and space.

Once we start looking, the swing appears in the most unexpected places. It shows up in ancient Greek swinging festivals, and cave paintings made in western India during the 5th century. It is illustrated in Chinese hand scrolls from the Song dynasty, from around the 11th and 12th centuries. It fills Hindustani and Punjabi paintings, such as Lady on a Swing in the Monsoon (1750-75), in which a woman joyously swings through the air, clothes fluttering behind her, as dark clouds grow in the distance. The swing also finds its way into the origin stories of the Persian Nowruz New Year celebrations, when people swung to mimic the way the legendary Shah Jamšīd rode his chariot through the air. It also turns up in Thailand’s Chakri dynasty in the 18th century, when a giant version was built by Rama I. And it is spread across the pages of Western literature and philosophy – Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-5), James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890), Sigmund Freud’s Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), and Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (1938).

The instrument we find in our urban playgrounds has travelled to us on a long and winding path. However, following that path backward is not without its difficulties. Though many instruments and gestures that come to us from antiquity are significantly altered on their passage to the present, the swing has mostly remained intact. We find versions of it scattered across almost every city in the world. This may seem advantageous, but having an instrument essentially identical to those found in ancient Greece, China or Persia has its drawbacks. For one thing, the ubiquity of the swing in our modern playgrounds means it is today regarded as puerile in its uses and irrelevant in its meaning. It is also an object, and experience, with which we are so familiar that we do not consider it worthy of serious thought. And, finally, it has suffered the fate of many other objects neglected by adults: it has ended up in the hands of children.

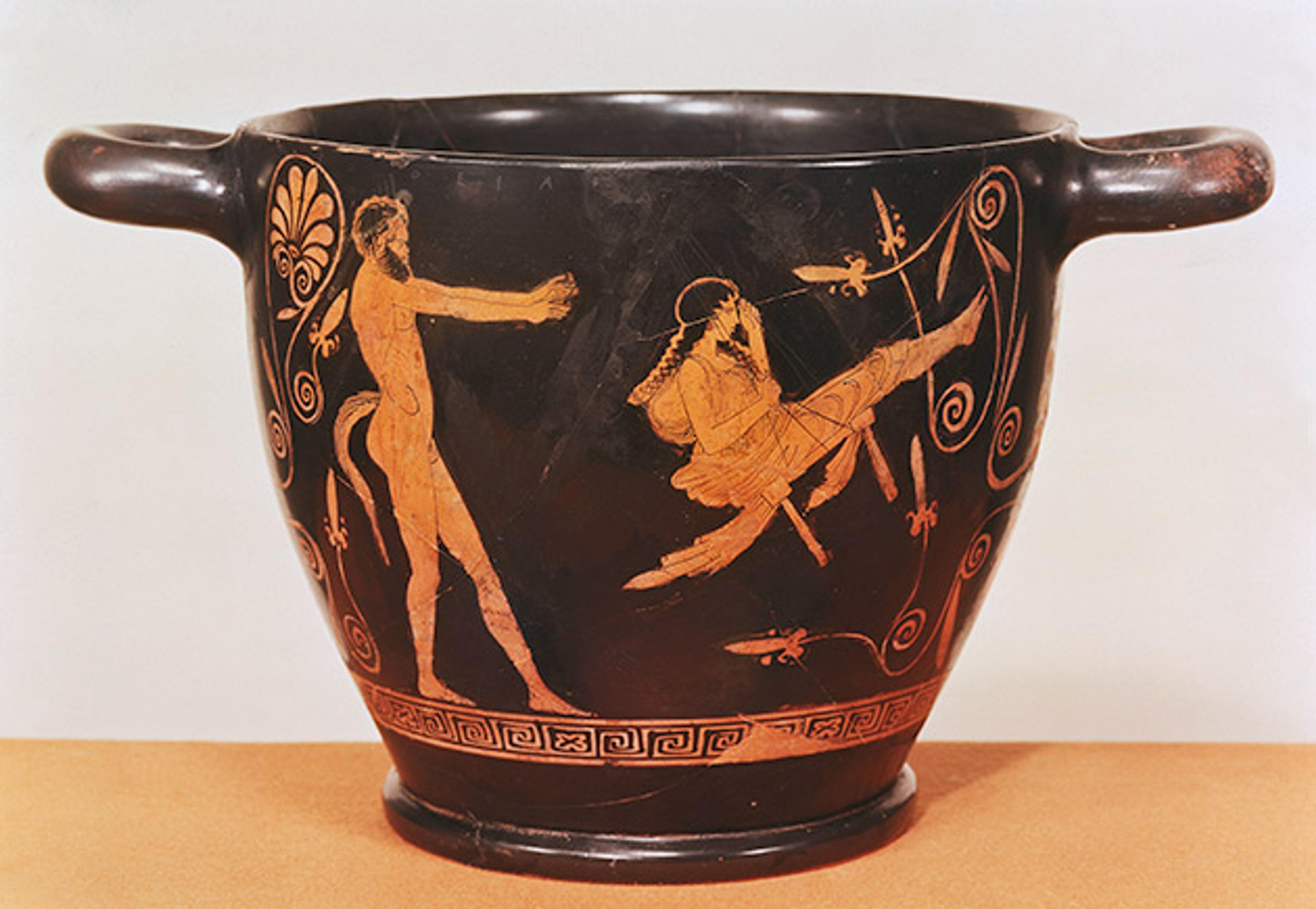

To claim that suspending the body from a rope and swinging it is necessarily a childlike and joyful experience is nothing more than prejudice. For thousands of years, the combination of suspension and swinging has served punitive or therapeutic practices far removed from jouissance or childhood. In classical Greece, the word aiora referred to both the swing and the noose on the gallows. This shared meaning emerges through the story of Erigone in the Bibliotheca, that great compilation of myths written by Pseudo-Apollodorus between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. In it, we learn that the god Dionysus taught Erigone’s father Icarius the art of winemaking, and that he shared what he made with his shepherds.

According to the most widespread version of this legend, the shepherds drank so much they thought they had been poisoned, so they killed Icarius. They attempted to hide his body by burying it at the foot of a tree, but the young Erigone found her father’s corpse. As the story goes, ‘she bewailed her father and hanged herself’, swinging from the same tree where Icarius was buried. It was then that Dionysus, or Erigone herself (according to some versions), cast a spell on the city of Athens, leading its virgins to hang themselves too.

According to Gaius Julius Hyginus, a 1st-century Hispanic Latin writer, the Athenians ended this sad epidemic by instituting the practice of swinging themselves while seated on wooden planks hung from ropes. Their bodies could sway in the wind like Erigone. In these accounts, we find one of the earliest interpretations of the swing’s (mythological) origins: a device of death that became apotropaic, or capable of warding off an evil spell, thus preventing young Athenian girls from hanging themselves. According to Hyginus, the swing began as a magical object, a machine for lifting a curse.

Doctors believed that the sweating, retching or vomiting that accompanied swinging could be therapeutic

Over time, the swing’s uses slightly changed as it appeared in different cultures. It became an instrument of play and discipline. Swinging can produce different, even contradictory, experiences in similar ways to the practice of ‘blanket tossing’, in which a person is punished or celebrated by being tossed into the air and caught on an open blanket held taut by a group of people. One example of the swing’s disciplinary uses is the ‘witches’ cradle’ – a coarse sack cloth hung from a tree, which served the same purpose as a similar swinging device known in North America and England as the ‘dunking stool’ or ‘cucking stool’. Beginning around the 15th century, those accused of witchcraft were placed in the sack, suspended and then swung back and forth, not unlike some forms of contemporary ‘aerial yoga’.

Even when it wasn’t used punitively, the swing still produced undesirable effects. On many occasions, and in essentially pedestrian societies, those who swung often experienced vertigo and dizziness. Others experienced a fear of falling as they swung, either due to an overly long rope or a saddle that threatened to break. Swinging was not always a positive experience. Well until the end of the 18th century, European and American doctors worked with this discomfort, believing that the sweating, retching or vomiting that accompanied swinging could be therapeutic. In the 1820s, the Czech anatomist Jan Evangelista Purkyně, known for delving into the labyrinth of the inner ear, confessed that he had suffered unspeakably while subjected to the rigours of swinging. To explore the ear’s labyrinth, the Czech sage had set up a rotating chair suspended by a rope, a device not unlike those used at the time for the treatment of various forms of insanity, and very similar to the swinging machines that were becoming popular in the parks and fairs of Bohemia. After swinging in his device for an hour and a half, he described his suffering as unbearable.

But swinging has not only been a source of physical discomfort. It’s also a source of horror. The history of spiritualism contains numerous references to swings (or pendulums). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the Sherlock Holmes character, included one in his History of Spiritualism (1925), and Victorian photographers, so prone to portraits of the dead, depicted apparently dead girls on swings. The trope of a ‘haunted swing’ that moves on its own would reappear in the horror films and amusement parks of the 20th century.

Capable of healing and punishing, the swing has been repeatedly used throughout history as a ritual instrument. It is an object primed for ceremony because it contains both Apollonian and Dionysian elements. In The Golden Bough, Frazer, an anthropologist, describes 21 examples of ritual swinging, from Nepal, Korea, Indonesia, Greece, Pakistan, Borneo and other locations where it was used as form of sympathetic magic (swinging higher to make grain grow taller), a means of warding off evil, or way to celebrate.

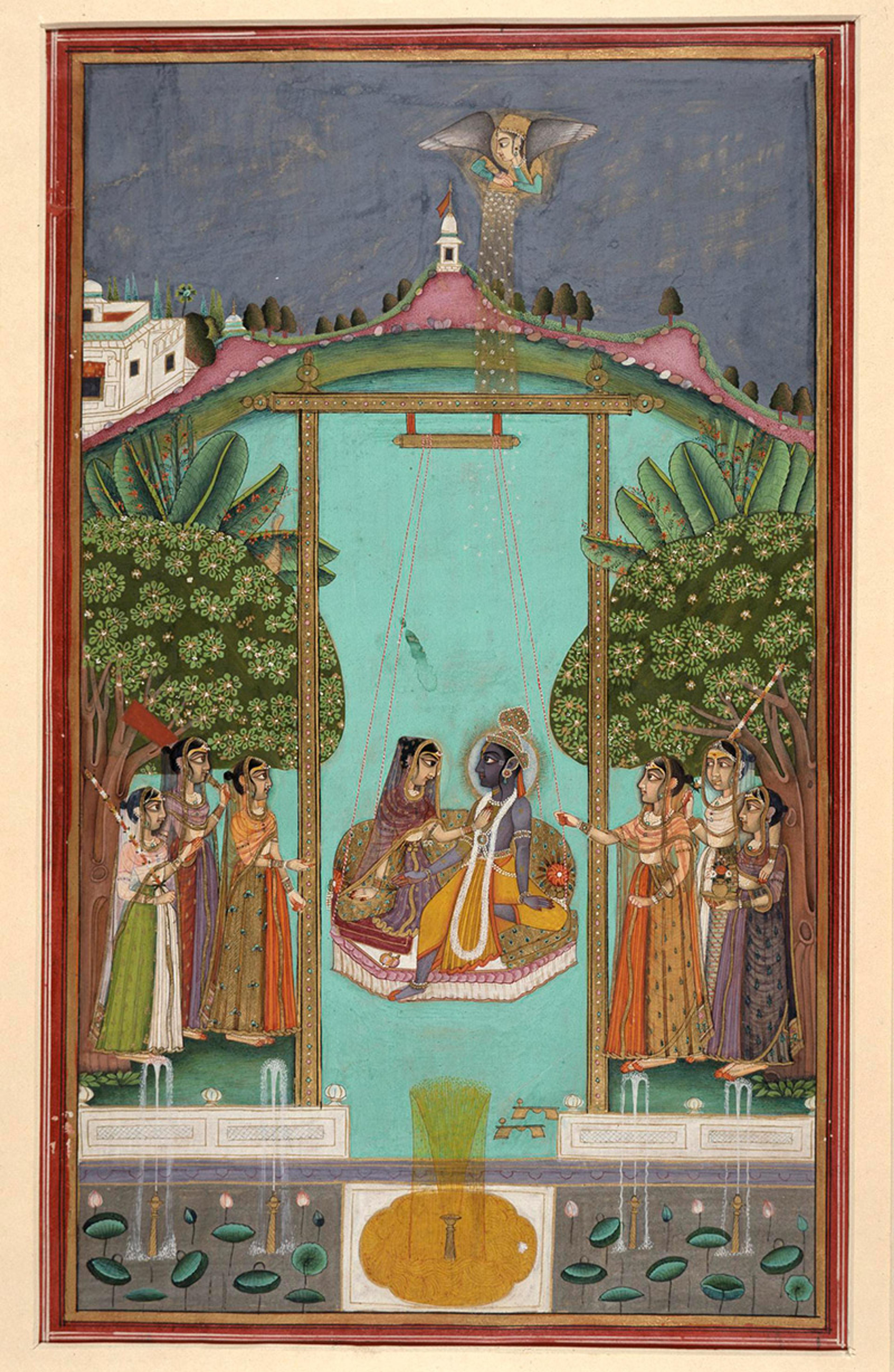

But why did swinging becoming ritualised in these locations in the first place? Ritual swinging, whether used in classical Greece or imperial China, has been described according to a mythology of love and death that always begins with an irrepressible impulse, a transgressive force that produces an emotional and moral disorientation. This impulse at the heart of ritual swinging is sometimes understood in sexual terms, such as the desire of the gopī (Indian cowherd maidens) who give themselves to the god Krishna, as told in the Puranas – though swinging is not mentioned in the text, illustrations of these encounters have depicted Krishna on a swing beside a gopī.

Historically, it was women who voluntarily submitted to ritual swinging, a provisional reversal of status

Krishna and Rādhā on a swing surrounded by female attendants called gopis (milkmaids); Rajasthan school, 18th century. Courtesy the British Museum, London

This impulse may also be expressed through the desire for suicide, as happened to the young Athenian girls who found the swing instead of the gallows. Sometimes this impulse will be the subject of psychoanalytical enquiry, as it was for Freud when in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality he wrote about the rhythmic sucking of thumbs and other ‘pleasurable sensations, caused by forms of mechanical agitation of the body … such as swinging’. For Freud, swaying was associated with a sexless sexuality that, once repressed or sublimated, manifested itself through adult experiences of nausea and vomiting when travelling on rocking trains or boats. These deeper impulses seem to drive ritual swinging.

But when it is part of a ritual, swinging can happen only at specific times and places, whether in the Nowruz celebration in Persia, the Eid-al-Fitr in Muslim Africa and the Middle East, or the swing festivals of northern Thailand or southern Spain. In China, that specific place was a fenced-in garden where the wives and concubines of wealthy Ming dynasty families would meet to sway on swings. There is a gendered dimension to this ritual action: historically, it was women who voluntarily submitted to ritual swinging, engaging in an act that was essentially nothing more than a provisional reversal of status. Through the swing, those who occupied a structurally inferior social position could free themselves from their situation of servitude – at least temporarily.

Using swings, we can artificially stimulate our vestibular system, the sensory system that gives our brain information about balance and position, putting us into a new relationship with our sense of orientation. Sometimes, this can produce uncomfortable effects, like vertigo. In the modern world’s treatises on motion sickness, vertigo is described as a state of false consciousness in which the earth is mistakenly perceived to be moving. Swaying back and forth, the perceiver searches for the flying shadows cast on their retinas, ultimately believing themselves to be what they are not. Unlike in mental illness (or even childhood), those who swing are subject to a state of disorientation that is initially physical, but that may also become emotional and even political.

This dissociative element, believing oneself to be what one is not, has made it possible for the swing to become symbolically and imaginatively charged. The swing is neither a horse, nor a rug, nor a pitchfork, nor a broom, nor a boat, nor a penis, but it has been able to embody each one of these things, to signify them and replace them, to some extent. Through this, swinging has enabled the creation of fictional spaces across the planet. It has been a source of aesthetic authority as much as an instrument of reverie. In India, one of the images associated with the aesthetics of the monsoon season – referred to as hindola rāga – is the representation of Krishna and Rhādā together on a swing. In The Peony Pavilion, the dramatic play written by Tang Xianzu at the end of the 16th century, the protagonist dreams about her love by painting a ‘garden scene with swing’. And in the ‘Qing Court Version’ of the Chinese scroll painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival, illustrated in 1737, the swing is depicted as an instrument of reverie, a moment of pleasure and calm amid the commotion of daily life.

Along the River During the Qingming Festival, illustrated in 1737. Courtesy the National Palace Museum, Taiwan

The experience of oscillation, of swaying back and forth, is part of a barely conceptualised visceral economy in which the body feels liberated from world-ordering social rules. This liberation didn’t take place only during ritual celebrations. Consider Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s rococo masterpiece The Swing (1767-8), a painting showing a woman in a ruffled pink dress, gleefully swinging high above a man in the bushes below who is looking up her skirt. According to Heaven and the Flesh (1995) by the scholars Clive Hart and Kay Gilliland Stevenson, The Swing is Fragonard’s inversion of sexual intercourse, a subversive ‘depiction of explicit female dominance’.

Before it was relegated to the playground, swinging made it possible to question hierarchies and find emotional relief

The Swing (1767-68) by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Courtesy the Wallace Collection, London

Those who have swung throughout history, women for the most part, have often done so to occupy a position of privilege or dominance, symbolically and physically, as they rose high above others. In the case of The Swing by Fragonard and other swing paintings – including those of Jean-Antoine Watteau and Francisco Goya – the scenes focus above all on the enjoyment of social transvestism, as traditional sexual and gender roles are exchanged. Before it was relegated to the playground, swinging made it possible to question hierarchies and find emotional relief from oppressive situations and conjunctures. As a release from physical restraints and social conventions, swinging can become an emotional refuge. Like those who seek solace in poetry, it provides a welcoming space within which to shelter from political storms, social roles and personal tragedies.

-_The_Swing_-_Keinu_-_Gunga_(29358967782).jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

The Swing (c1712) by Jean-Antoine Watteau. Courtesy Wikimedia

The Swing (1779) by Francisco Goya. Courtesy the Prado Museum, Madrid

However, swinging may not always be transgressive. Sometimes, it can entrench the established order. We see this during rituals, when the swing is involved in a stage drama. Like the actor who knows that he is only playing, those who swing also have a split consciousness: by rising and falling, or swaying back and forth, they understand that the rules of orientation can be questioned, but they also know that swinging is a prescribed exercise of obligatory compliance, permitting only certain kinds of movement. Swinging has the character of a voluntary activity, but only in appearance.

In addition, though swinging questions the physical and social orders through physical and emotional disorientation, it still leaves everything as it was. It is a game of deception. At best, it produces only a provisional liberation from servitude, not emancipation. In the Akha swinging ceremony in northern Thailand, for example, it is the women who adorn themselves and swing. For a few days each year, while they dress up, swing and enjoy themselves, they will not feed the pigs, work the land, or fetch water. However, far from modifying unequal conditions, the ritual perpetuates the status quo. After the swinging has ended, all return to their duties and chores. The same positions of subordination and domination are maintained once the ritual ends.

The swing, a machine that mobilises such human experiences as vertigo, disorientation or anguish, is also a metronome over which a mantra can be recited. From the classical Greek Dionysian festival known as Anthesteria to the Livonian festivals in Latvia, ritual oscillation is often accompanied by chanting and dancing. The connection is explicit in the pre-Columbian (perhaps Totonac) sculptural ‘swing’ in the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa in Veracruz, which doubles as a musical instrument. Since antiquity, the ritual uses of the swing have often been linked to musical structures or rhythmic variations. In the 4th century BCE, Plato argued that the disconsolate crying of children could be controlled by imitating the sound and motion of the waves. Instead of promoting silence, he argued that mothers could bewitch their children through the combined action of movement and cooing, just as priestesses did with the followers of Dionysus. The same oscillating movement could comfort children or soothe fanatics.

Depiction of the Anthesteria festival, ancient Greek vase. Courtesy the Altes Museum, Berlin State Museums

Swing figurine, 300-900 CE. Courtesy the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

The combination of swinging and song has two important consequences. First, in the Teej festivities in India, the festivals of the Akha people in southern China, and the Festival of Swings in the town of Ubrique in southern Spain, young women use the cadence of the swaying movement to sing songs that call into question the unequal distribution of inheritances or work, to express their fear of being mistreated by their future partners, or the conditions under which their marriages have been arranged. They are songs of love and terror, sung in times of licence. They may have a festive character, but not all their lyrics are positive – some, as in the case of the festivities of the swing in classical Greece, are linked to the threat of suicide.

The second consequence is that singing during swinging rituals is also related to the formation of communities of experience. Across the world, women dress up, swing and sing together. Far from being an individual pastime, the ritual action is part of a planned process of social reversal that implies the formation of a community. While swinging, the concubines of the great families of imperial China could move together, for a while at least, and glimpse what life looked like over the walls of their fenced-in garden. The Akha women, as much as the girls of Tamil Nadu in India or of Ubrique in Cádiz, could temporarily put an end to their gender obligations and climb on swings, with the illusion of freedom and emancipation. All these rituals invert the hierarchical regime, allowing the transposition of estates, classes and genders. Whoever is at the bottom can play at being at the top, and whoever is at the top goes at the bottom. It’s a form of social transvestism that has often been associated symbolically with the power of sex, as women are temporarily placed in a dominant position.

Celebrations of the rising of the river were accompanied by sexual rituals relating to the position of the swing

The history of the swing is not only related to the primal impulse of swinging, but to the sexual posture that a woman can use to mount her lovers, as in Fragonard’s painting. This history cannot be told without referring to this inversion of sexual roles. The sexual position known as Venus pendula or mulier super virum (‘woman on top of the male’) finds its founding myth in the Cult of Isis, which spread through the Hellenistic kingdoms in the 3rd and 4th centuries BCE. The myth goes like this: upon learning that the body of Osiris had been torn to pieces and spread across Egypt by the god Set, Isis searches for his remains by sailing across the marshes. When she finds his penis, and sees that it retains a modicum of life, she perches on it and tucks it inside herself while adopting the shape of a hawk. In a papyrus preserved in the Louvre Museum in Paris, this form of conception is described in the following words:

I am your sister Isis. There is no other god or goddess who has done what I have done. I played the part of a man, although I am a woman, to let your name live on earth, for your divine seed was in my body.

During the 2nd century CE, around the time Apuleius wrote his Metamorphoses – in which we find the first reference to Venus pendula in a story about a young protagonist, Lucius, who is turned into an ass and falls under the protection of the Goddess Isis – the festival in honour of Isis known as Navigium Isidis was in full force in the Roman world. In the festival, a procession would emulate the movements of the sea, but also the sexual oscillation of the goddess as she rests on the penis of Osiris. The image of a woman on top of a man, what we call the ‘cowgirl’ position today, is not only found in ancient Egypt but attributed by the Romans to the societies of the upper Nile. History has bequeathed us no shortage of visual evidence showing that celebrations of the rising of the river were accompanied by sexual rituals relating to this sexual position – the position of the swing. One appears in the frescoes adorning the walls of the columbarium of the Villa Pamphili in Rome, painted during the reign of Emperor Augustus and now in the collection of the National Roman Museum, in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme.

Erotic fresco from the House of the Centenary, Pompeii. Courtesy Wikipedia

The history of the swing, a forgotten chapter in the history of humanity, is crisscrossed by both mythologies and ritual processes. Whether we are talking about classical Greece, ancient Persia, pre-imperial China or ancient Egypt, the history of the swing is permeated by the perseverance of common traits and shared myths: drunkenness, love, murder, suicide or ambition revolve around an inevitable impulse, like that of Erigone who hangs herself after finding her father’s corpse. On the other hand, these legends and stories would be nothing without the social process in which they are embedded, without their collective, ritualised forms that allow the telling and retelling of very similar stories. Through the swing, and swinging, we see the ways in which communal culture and social rule are inscribed, ritualistically, imperceptibly, into the body through time.

So, why do we swing? The instrument that populates our urban playgrounds may have travelled to us on a long and winding path, but its origins elude us. The survival of swinging as a common gesture cannot be resolved by appealing to an ancestral history from which each new movement is merely a derivative. The origins of our preference for swinging are not fixed in any record. They are situated in the nebula of the legendary, long before there was any concern to inscribe events in a chronology.

This essay develops ideas discussed in the book The Arc of Feeling: The History of the Swing (2023) by Javier Moscosco, published by Reaktion Books.