One weekend in March 1995, a group of librarians and web technologists found themselves in Dublin, Ohio, arguing over what single label should be used to designate a person responsible for the intellectual content of any file that could be found on the world wide web. Many were in favour of using something generic and all-inclusive, such as ‘responsible agent’, but others argued for the label of ‘author’ as the most fundamental and intuitive way to describe the individual creating a document or work. The group then had to decide what to do about the roles of non-authors who also contributed to any given work, like editors and illustrators, without unnecessarily expanding the list. New labels were proposed, and the conversation started over.

The group was participating in a workshop hosted by the OCLC (then the Online Computer Library Center) and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) in an attempt to create a concise but comprehensive set of tags that could be added to every document, from text files to images and maps, that had been uploaded to the web. Arguments about these hypothetical tags raged over the course of the next few days and continued long into the night, often based on wildly different assumptions about the future of the internet. By Saturday afternoon, the workshop co-organiser Stu Weibel was in despair of ever being able to reach any kind of consensus. Yet by the end of the long weekend, the eclectic crowd had created a radical system for describing and discovering online content that still directly powers web search today, and which paved the way for how all content is labelled and discovered on the open web.

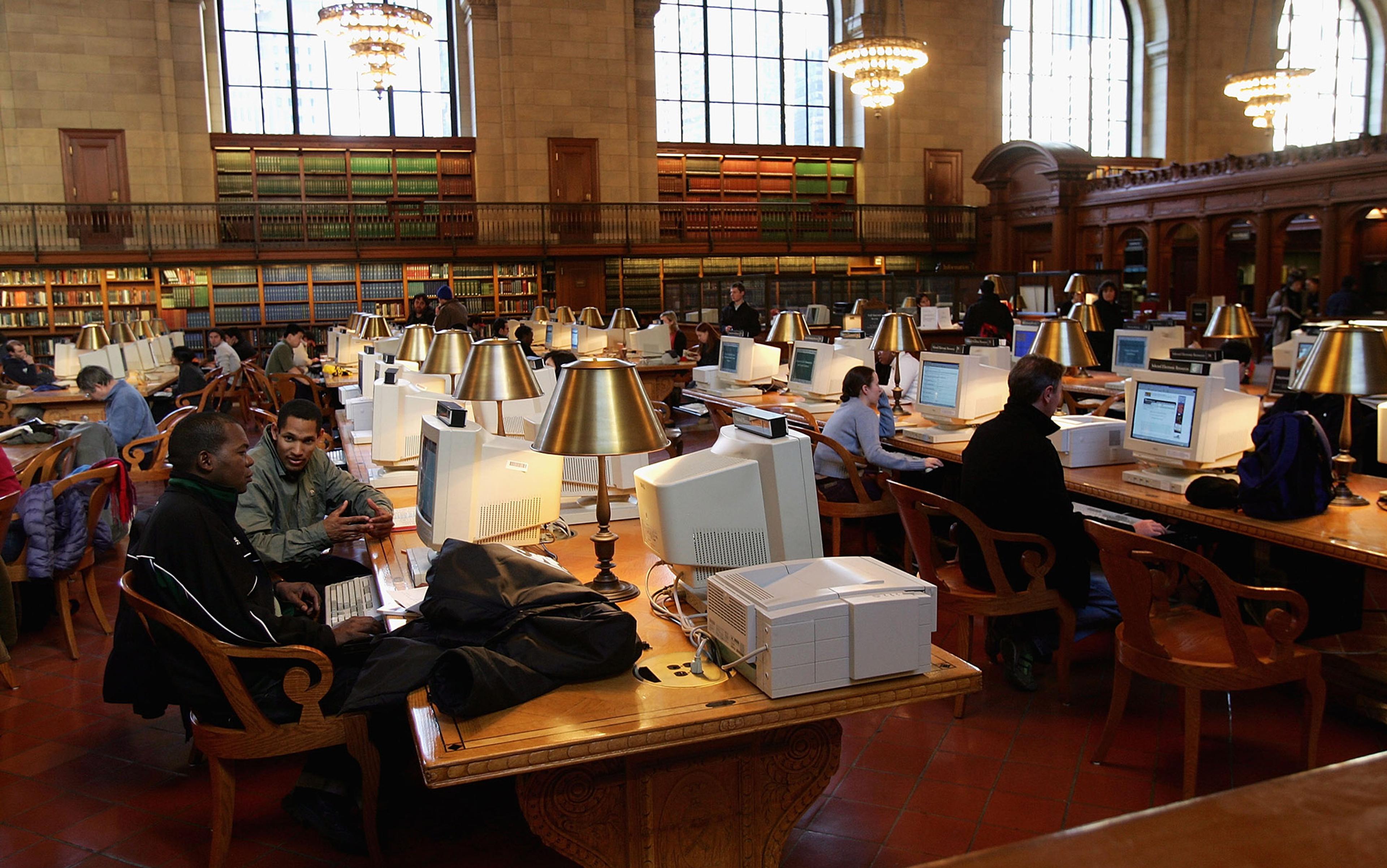

Representatives of libraries and publishers and also of the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) at the 1997 Canberra conference. Courtesy Thomas Baker/Dublin Core.

Two recent developments had added importance, and pressure, to the 1995 conference: the recent launch of Mosaic, the first widely available web browser; and the subsequent rapid pace of content being uploaded online. Mosaic, which became available to the public in 1993, had a graphical point-and-click interface that anyone could use. Mosaic removed the need to write your own interface to explore the web, so suddenly anyone could go online. Public use of the web leapt dramatically. Mosaic also allowed users to upload their own text documents, images and video online, leading to a spike in content scattered across the web. Meanwhile, a large and growing set of scholarly materials had been moving online throughout the early 1990s, and university librarians were among the first people flagging how difficult these files were to find.

By 1995, there were half a million unique content-rich pages, text files and other ‘document-like objects’, as the workshop participants called them, on the web, but no good way to search for them without already knowing where and what they were. Early web-search tools, such as Archie and Gopher, could query only for the titles of the files themselves or their locations, meaning that you had to know either the exact name of the file you were looking for, or else where it was located (its full URL, or Uniform Resource Locator). So, for example, if you wanted to find a copy of an essay that you thought someone had posted online, you couldn’t just search for the author’s name and the title of the essay. This barrier made many, if not most, online documents essentially inaccessible to most people. As Weibel wrote in his report for the 1995 workshop: ‘the whereabouts and status of this [online] material is often passed on by word of mouth among members of a given community.’

To make these files truly discoverable for users, some kind of tagging system with top-level information, such as author and subject, was needed: in other words, metadata. In this context, metadata can be thought of as a short set of labels associated with the document that allow you to both find it and know what it is without opening it.

To develop a system that worked, they needed input from ‘the freaks, the geeks, and the ones with sensible shoes’

Librarians have been creating bibliographic metadata for thousands of years. For example, at the Library of Alexandria, each papyrus scroll had a small tag attached to it with information about the title, author and subject of the scroll, so that readers didn’t need to unroll it to know what it was. Librarians could also use these tags to properly re-shelve the scrolls in pots or shelves.

Now the web needed the same thing.

The workshop to solve this problem began as a hallway conversation in 1994 at the second International World Wide Web Conference in Chicago. Weibel, who worked in the research group at the library consortium OCLC, was standing around drinking coffee in the hallway with five or six people, including his boss, Terry Noreault, and Eric Miller, his colleague on the OCLC research team. As Weibel remembers: ‘We were talking about how nice it would be if there were easier ways to find the 500,000 individually addressable objects [documents] on the web … I looked at my boss, and he just nodded and agreed to organise a workshop for it.’

The workshop was quickly co-organised by Weibel and Miller, who wanted to be able to take the results to the next web conference in Germany the following spring. In order to develop a system that worked, they knew they needed input from three different groups of people: encoding and markup experts in specialised disciplines, who could help ensure that metadata was effectively associated with the online files; computer scientists; and librarians, or, as multiple people who attended the first workshop told me with deep affection, ‘the freaks, the geeks, and the ones with sensible shoes’.

Some 52 people showed up to the workshop in Dublin, Ohio. The variety of attendees, and their perspectives on how documents on the web should be organised, was striking. As Priscilla Caplan, a librarian who attended the conference, wrote at the time: ‘There were the IETF [Internet Engineering Task Force] guys, astonishingly young and looking as if they were missing a fraternity party to be there. There were TEI [Text Encoding Initiative] people … geospatial metadata people … publishers and software developers and researchers.’ All had very different goals, but ‘nearly everyone agreed that there was a tremendous need for some standard’.

In 1995, most librarians were using MARC (MAchine-Readable Cataloguing) to create metadata for their library catalogues. MARC records are complex, extremely long, and require deep expertise to create. These kinds of elaborate descriptions could never work at scale for the entire web. Automated approaches weren’t on the table back then, and it soon became clear to all attendees, even those who had showed up thinking that they might be tweaking an existing system, that the metadata standard for the web would have to be something entirely new: simple enough for anyone to label their own documents as they posted them online, but still meaningful and specific enough for other people and machines to find and index them. A brand-new, simple and succinct metadata system would mean that, for the half a million existing items online, and the millions and billions more that everyone knew were coming, there would need to be one agreed-upon way of adding the metadata tags, with the same kinds of information in the tags themselves.

Creating these labels involved figuring out not just what would be needed to find files that were online now, but also what might be needed later as web content continued to snowball. There was no formalised voting or veto process to come up with the system; each piece of metadata was created through consensus, compromise and, occasionally, real fights. Much of the argument, in fact, concerned the nature of the future no one could truly predict in full.

For example, many attendees didn’t anticipate that automated search engines were coming, though some of the more technical people saw them on the horizon and were pushing requirements for improved geolocated discovery. As Miller says: ‘I remember introducing the [geolocation] coverage element and getting a lot of blowback. I made the point that coverage is going to be local as well as global, like: Find a restaurant near me. We were trying to push the envelope so that we would be ready when other technologies advanced and other services became available.’ Other attendees saw geospatial data as something put in to assuage a person or community, and they weren’t sure it made sense given the need to keep the system lean.

In the beginning, the disagreements seemed insurmountable, and Miller felt disheartened: ‘The first night we thought: This is gonna fail miserably. At first nobody saw eye to eye or trusted each other enough yet to let each other in and try to figure out the art of the possible.’ But as concessions and then agreements were made, people began to feel energised by the creation of a new system, even if imperfect; one piece at a time, their system could bring the content of the web within reach for everyone. As Caplan remembers: ‘By the second day, there was a lot of drinking and all-night working groups. We were running on adrenaline and energy. By the last day, we realised we were making history.’

Dublin Core was revolutionary in its creation of a very new middle ground

The result of all the arguments was ‘Dublin Core’ (DC) metadata, the first metadata standard for describing content on the web. The final short group of DC tags, or metadata ‘elements’, was drawn from a longer list that had been developed, iterated, analysed, argued over, and eventually cut down to a list of 13. In his workshop report, Weibel provided an example of the elements, using the University of Virginia Library’s record of Maya Angelou’s poem ‘On the Pulse of Morning’, transcribed by the library from Angelou’s performance at Bill Clinton’s inauguration:

- Subject: Poetry

- Title: On the Pulse of Morning

- Author: Maya Angelou

- Publisher: University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center

- Other Agent: Transcribed by the University of Virginia Electronic Text Center

- Date: 1993

- Object: Poem

- Form: 1 ASCII file

- Identifier: AngPuls1

- Source: Newspaper stories and oral performance of text at the presidential inauguration of Bill Clinton

- Language: English

Fiercely truncated compared to a library catalogue record (MARC records have 999 fields) and simple enough that anyone could create them, DC was revolutionary in its creation of a very new middle ground: a record ‘more informative than an index entry but is less complete than a formal cataloguing record’, as Weibel wrote in his 1995 report. DC tags could be created manually and easily by anyone, not just a librarian, allowing for more documents to be described in a standardised way so that automated tools could index them comprehensively. The ease and simplicity of DC tags, while still being specific enough to be meaningful, were key to their success. As Miller explains, DC ‘makes the simple things simple, and the complex things possible.’

Today, DC looks very familiar and even obvious, in part because it has so deeply influenced the way that metadata is embedded into webpages. Metadata tags, or ‘metatags’, are now a fundamental infrastructure for the open web, where they usually take the form of HTML (HyperText Markup Language), the most used system for displaying content in a web browser. HTML metatags label pages for crawling and indexing by search engines like Google and other web-scale search services. For example, the metatag ”dc.Author” content=”Maya Angelou” /> is flagged and parsed by web indexers to mean that the author of the content on the webpage is Maya Angelou. The information embedded in metatags is used for matching queries to search engine result pages; much of SEO (search engine optimisation) work is just adding comprehensive, detailed metatags.

The original DC metatags are still being used globally today, and they also directly influenced many others, from the Web 2.0 metatags for social media posts to generic and specific tags for various types of content-rich HTML pages on the web. For example, the Poetry Foundation’s electronic version of ‘On the Pulse of Morning’ contains multiple sets of metadata embedded into the HTML source code: from standard DC metatags, like <’dcterms.Title’>; to tags for Twitter/X, like the <’twitter:image’> tag used to add an image when the poem is shared on the platform; and the Open Graph tag <’og:see_also’> that Facebook/Meta uses to point users to related content.

DC has directly influenced and shaped the past 30 years of finding things on the web, from RSS feeds to the data models underlying the knowledge graphs and panels that make up the information cards on the front page of Google search results. Miller, who moved from DC to the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the group that oversees standards, protocols and languages for the entire web, told me: ‘You can connect any web standard back to certain DC characteristics, lessons learned, or principles … A lot of the stuff that came out of the global standards was directly to solve the industry standards that DC defined.’

The summer after the 1995 workshop, the librarian Lorcan Dempsey, then located at the University of Bath and leading the UK Office for Library and Information Networking (UKOLN), offered to help spread the standard. Dempsey helped to run future workshops, initiating with Weibel the annual conference series known today as the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI), which still meets to make tweaks and pose arguments about what changes will be needed for the future. But the core set of metatags has remained remarkably stable. As Weibel told me: ‘After two and a half days, we had reached general consensus about what the elements should be, as well as their characteristics. People are still arguing at Dublin Core conferences, but we did a pretty good job of figuring out the basic skeleton.’

Uptake was quick for the brand-new standard. In 1997, Weibel was at a small workshop in Bonn, Germany, where he learned that a team in Germany, led by Roland Schwänzl at Osnabrück University, had added DC tags for their content pages, representing the first real-world use of the metatags. That moment was critical for Weibel as the point when he saw that this would actually work for people: ‘It marked the first time that I realised the impact of this navel-gazing that we were doing: other people without an intellectual stake went and built systems based on it.’ Once the standards were encoded, the ‘navel-gazing’ had become legacy code, and DC was real.

If there was magic about Dublin Core, it was the social process, not technology

Everyone I interviewed who attended the first few workshops still seems surprised that they managed to reach consensus at all after just a few days, and they all assert that this agreement was as remarkable a product as the list of metadata elements itself. The structure of productive disagreement, and sharing different visions of where things were going, was part of the success. As Weibel describes: ‘The real product, in a way, was consensus. It almost didn’t matter what we ended up with. It wasn’t rocket science – there was no magic about it … we simply had shared problems that needed to be addressed, and it worked.’ If there was magic about DC, it was the social process, not technology, set against the backdrop of profound optimism at the possibility of a new world.

What made the conference difficult was also what made the standards work: the diversity of those involved. Caplan describes the workshop as at times reminding her of the bar scene in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: ‘dozens of alien species milling about and talking slightly different English-like languages.’ The consensus-driven success of DC, led by a diverse, non-commercial group from wildly different fields, would, frankly, be almost impossible today; even the concept of bringing together a heterogeneous web community to solve web-sized problems with neutral, open standards now seems quaint. DC also encouraged broad use of metadata to improve description and organisation of digital resources, leading to a more connected and discoverable web ecosystem. That ecosystem is disappearing rapidly in the platformised, hyper-corporate space of the current web.

Much of DC’s success had to do with the lack of online commercial activity at the time. Only a few years previous to 1995, the National Science Foundation Network had updated their acceptable use policy to allow commercial traffic. As Weibel describes: ‘Nobody had the blinding light of startups in their eyes … The lack of commerce on the web was in part what allowed there to be an open standard, with real neutrality. Of course, that didn’t last long. It’s hard to imagine now. Everyone wants to start a company.’

The future of the web is firmly moving in the opposite direction of DC values around transparent approaches for information discovery. Large commercial tech platforms work hard to keep users in their walled gardens by utilising in-app black-box algorithms rather than linking out to external locations. Generative AI tools are incentivised to replace exploration of the open web, and almost none of the current text-based generative AI tools cite their sources.

These changes mark what is often described as the end of the open web, where corporations centralise services and invisibly control what you see when you try to find something, with business models that are ever more incentivised to move away from interoperable web standards. The historical period of the open web, which arguably began with Mosaic 30 years ago, is already receding, and perhaps has already ended; the story of DC bookmarks the historical moment of when this era was new, and when the web was a source of almost pure optimism.

The year ‘1995 was an amazing time, just between two worlds,’ Caplan remembers. ‘There was a strong sense that a new information environment was emerging, something like a new dawn,’ Dempsey adds. That environment is now gone, with DC tags acting as a still-functional artefact. As one DC participant told me: ‘That environment, which was just emerging, has disappeared, along with that sense of a movement combined with a standard – what we’re left with is the standard.’