My introduction into the world of Afghanistan’s Sufism began in 2015, over lunch with my friend Rohullah, the director of a research institute in Kabul. I had been working in Afghanistan in various sectors from government to nongovernmental jobs, and had returned to explore topics for a PhD that I had embarked on, a year prior.

I asked what had happened to Afghanistan’s Sufis. Were they all gone? Afghanistan had, after all, once been the cradle of mystic interpretations of Islam, the place of origin of Mawlana Jalaluddin Balkhi, known in the West as Rumi. Had the Sufis disappeared in the exodus precipitated by successive wars that had engulfed Afghanistan since the late 1970s? Or had they been replaced by more radical and austere forms of Islam, as some analysts speculated? Rohullah laughed. ‘They are still here,’ he said. ‘You foreigners just don’t ask about them. All you care about is gender, counter-insurgency and nation-building.’

Any cursory look through titles in bookstores or newspaper headlines on Afghanistan substantiated Rohullah’s insight: Western policymakers, journalists and most researchers tended to nurture the kinds of knowledge about Afghanistan that informed policy, and for that purpose Sufis were not particularly useful. But even when searching regionally for literature on Afghanistan’s Sufis, all I could find were texts on the historical prevalence and importance of Sufis, though nothing about their present-day lives and struggles.

On occasion, Sufism still burst onto the public stage, for instance in 2016 when Iran and Turkey tried to claim the Masnawi Ma’navi, Rumi’s magnus opus, as their joint cultural heritage (the poet died in Konya, in present-day Turkey, in 1273 – and wrote in Persian, a language spoken in both Iran and Afghanistan). Western scholars and pundits barely took notice but, in Afghanistan, public intellectuals such as the poet laureate and Sufi poetry teacher Haidari Wujodi argued that ‘Maulana belongs to present-day Afghanistan and yesterday’s Khorasan. It is the responsibility of the Afghan government to take swift action about it to protect our heritage.’ An online petition decried the attempt to lay claim to Afghanistan’s cultural legacy while the Ministry of Foreign Affairs held talks with UNESCO over the perceived slight. And Atta Mohammad Noor, the then governor of the northern province of Balkh where Mawlana’s family originated, penned a letter to the UN condemning Iran and Turkey’s ‘imperialistic’ attempts to appropriate Rumi and disregard Balkh as the esteemed poet’s ‘motherland’.

This ‘diplomatic frenzy’, as Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty called it, revealed Afghan pride in Sufism and that it still has the power to spark intense debate. Sufis in Afghanistan never really fit into Western narratives about the Taliban or the war and occupation. So, Sufism was ignored. The chaotic US military evacuation in 2021 and the sweeping Taliban takeover, with all the scenes of suffering and human rights abuses that followed, have made it even more difficult to imagine an Afghanistan where Sufi scholars debate the finer points of Islamic ontology and poets ruminate on the infinite ways to lose oneself in the beauty of God’s creation. It requires a real stretch to remember that Sufism, in its multifaceted incarnations, has been a central thread in the tapestry of Afghanistan’s historical, artistic, educational and political life. Sufi traditions were once so influential in royal courts that kings extended patronage to poets and Islamic figurative artists who illuminated manuscripts, weaving Sufi literary motifs into exquisite paintings. Some historians, such as Waleed Ziad, even go as far as to say that Sufi orders that were firmly rooted in what later became Afghanistan built their own ‘hidden caliphate’, creating networks throughout the Middle East, Central and South Asia.

These chapters remind us that Afghanistan’s history transcends the geopolitical tumult of the present, tracing back to a rich heritage of spiritual and artistic expression. The history of centres of Sufi learning, such as the Pahlawan Sufi lodge in an old part of Kabul, starts in this different time: in the 18th century, the capital shifted from southern Kandahar to the mountain-crested city of Kabul, a migration that ushered in a wave of cultural and spiritual transformation. Among those embarking on this northward journey was a man named Sufi Sher Mohammad and his son Mir Mohammad. Sufi Sher earned the sobriquet of Pahlawan, or ‘wrestler’, a testament to his reputed superhuman fighting prowess. But, also, a name to praise that he fought for the powerless. In the heart of Kabul, they built the Khanaqah Pahlawan, or the Lodge of the Wrestler, in a district fittingly named Asheqan-o-Arefan, a place where lovers and mystics, the seekers of gnosis, congregated in their pursuit of divine wisdom. Here, seekers assembled for weekly meditative zikr (literally, ‘remembrance of God’) rituals and spiritual advancement through reading and learning.

In the modern era, Sufism continued to play a central role in Islamic thought and practice in Afghanistan until at least the last quarter of the 20th century. Sufi poetry was not a fringe phenomenon but a mainstream approach to teaching Islam in Afghanistan’s madrasas. Alongside the Quran and Hadith, students learned poetic exegeses based on the compilations of Rumi, Saadi and Hafiz. ‘In the past, there was oral knowledge on how to understand, recite and sing poetry,’ an Afghan friend told me. ‘Until the Soviet time, [in addition to the Quran,] the mosques were also teaching poetry, through collections such as Panj Ganj … Now there is only learning by heart, no analysis.’

The Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, my friend pointed out, was a time of radical change and violence on multiple levels. Fighting and destruction sent many Afghans into neighbouring countries, while ideas about what constituted Islamic authority shifted during the jihad, fought against the backdrop of the Cold War.

Khanaqah Pahlawan’s spiritual lineage stretches back centuries but the structure of the Kabul lodge itself bears the scars of its journey through Afghanistan’s recent history. During one visit in 2018, Haji Tamim, the custodian, told me: ‘We had to rebuild the roof and upper floor two times,’ explaining how they were hit by rockets that had shaken the lodge’s foundations. ‘Then the mujahidin came,’ he continued. ‘They looted and burned everything that was in here. They took out all the dishes and all the stuff from the mosque [on the first floor] and from the khanaqah [lodge]. They took even the carpet from the mosque!’ In the era of the civil war, when various mujahidin factions fought each other, the khanaqah often found itself on the precipice of violence, its serenity disrupted by war.

The Sufi community sometimes chose to congregate instead in a mosque in another part of Kabul, where they continued their zikr sessions and spiritual studies. When they were finally able to return in the 1990s, the community came together to repair the damaged khanaqah. An extensive network of students and regular visitors pitched in financially and with labour to reconstruct the building. Sufis in Kabul use the khanaqah for meetings and celebrations, for rituals as well as a community space for studying poetry, hagiographic compendia and philosophy. Without any state support, Sufi religious networks coalesced, repaired and rejuvenated as best as they could.

This could have been the end of the Sufi lodge, its leadership starting new lives abroad

As I walked through the principal congregational chamber on the second floor, an elongated rectangular space adorned with richly patterned red carpets, illuminated by a cluster of chandeliers, Haji Tamim led me to a dark-blue metal cabinet tucked away in the room’s corner. He unlocked the cabinet and, with reverence, began retrieving a collection of relics. The first, a wooden walking stick, had once been the steadfast companion of Pahlawan Sahib, the founder of the khanaqah, more than two centuries earlier. As Haji Tamim cradled the staff, he told the history of each item.

Haji Tamim displaying the cap that belonged to Haji Ahmad Jan. Khanaqah Pahlawan, Kabul, 2018

They included a cap that had belonged to Haji Ahmad Jan, a respected teacher, whose prospects were bound to the tumultuous era of Hafizullah Amin, when the Communist coup of 1978 set in motion a harrowing, year-long campaign of ideological cleansing to assert control over religious education. In this brief yet catastrophic period, the estimated tally of the disappeared ranged between 50,000 and 100,000. Intellectuals who dared to critique the government, liberal thinkers, Maoists, religious scholars as well as those arbitrarily swept up in the purges found themselves ensnared in a web of persecutions. Even the devoted disciples and revered teachers of Sufi orders were not spared this repression, Haji Tamim recounted, his voice lowering. ‘Haji Ahmad Jan was the one leading the khanaqah. They came and dragged him outside and arrested him. When they manhandled him, he lost his cap. It fell to the floor. He never came back.’

The persecution of religious teachers by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) ultimately led to the most enduring transformations, including unlikely alliances that would guarantee the safety of the lodge and its members. These cherished relics symbolise not only the foundation of the khanaqah but also a turning point, marked by the Communist regime’s oppression, which forced the family that had been its steadfast guardians into exile. The teacher was arrested, and so were other members of the Pahlawan family who were detained for several years. At the time, one could never know whether an arrest would lead to an eventual release or disappearance. The Pahlawan family made the decision to leave Afghanistan for good – first to Pakistan, then India, before settling in the United States and Germany. This could have been the end of the Sufi lodge, its leadership starting new lives abroad, students dispersing to other places of learning or giving up their path altogether. But the family struck a deal with a quiet, unassuming mullah from another part of town: he would become the pir of the order, guarding the lodge and leading the community. Thus began the leadership of Haji Saiqal, the unlikely leader of Kabul’s Pahlawan Sufi community.

When Haji Saiqal went from the threshold of his mosque out into the streets in Kabul’s Microrayon district, dashing first through wide boulevards and turning into winding alleyways on his way to the reverent confines of the Khanaqah Pahlawan, he crossed multiple spaces and boundaries. At the mosque, the plainly dressed old man with his well-groomed white beard, signature flawless pirhan tumban and a modest turban on his balding head was the keeper of the Law, the imam who, five times a day, led prayers for a neighbourhood of believers. On Fridays, he delivered a sermon expounding the message of the Quran and the Hadiths. At the lodge of the Pahlawan Sufi community, Haji Saiqal was the keeper of a place of spiritual knowledge his followers believe brought them closer to God’s divine presence. Moving from one role to the other, from mullah to Sufi guide (pir) and back again, was as much – perhaps more – a spiritual transition.

This double role was also almost unheard of in the reporting on Afghanistan. In recent times, mullahs have become, perhaps unfairly, a disreputable class of Islamic leader, in both the East and the West. In its most basic sense, a mullah is an educated Muslim trained in Islamic theology and sacred law, holding an official post in a mosque as an imam. But this term embodies a wide spectrum of attributes, from esteemed community leader to rigid dogmatist to bumbling object of ridicule. Mullahs are believed to hold the potential to rouse fervent crowds or even frenzied mobs, particularly when their Friday sermons delve into politically charged terrain. Since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 2021, and its theocratic precursor in Iran in 1979, the geopolitical influence that ruling mullahs can wield has been a cause for both regional concern and strategic interest. But they can also be the butt of jokes, as with Mullah Nasruddin – a satirical character in the trope of the wise fool, well known in regional folklore from the Balkans to China; at times witty, at other times wise, he dispenses pedagogical humour that criticises the powerful and humbles the listener.

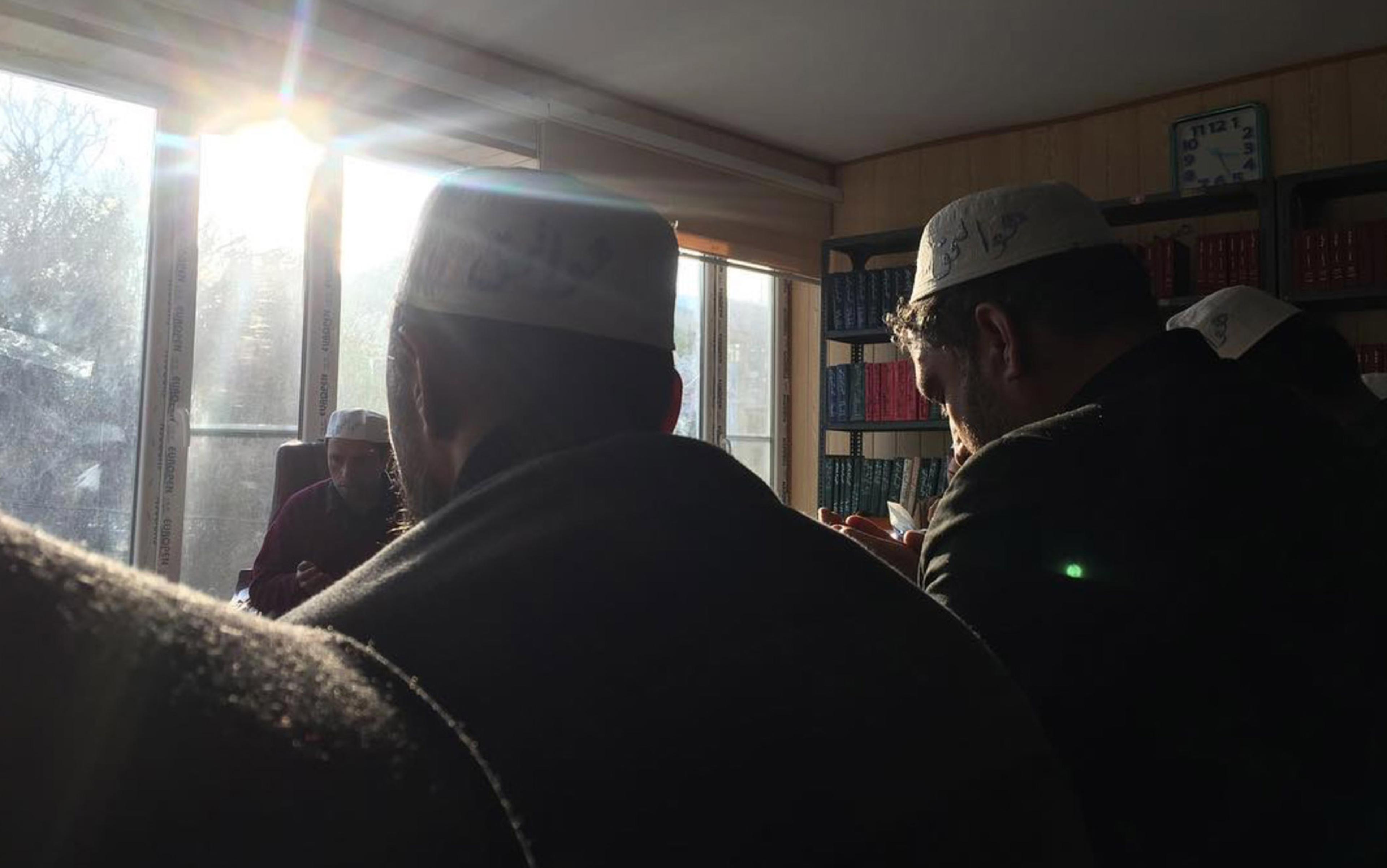

Zikr meeting at Khanaqah Pahlawan, August 2021

Regardless of where they fall on the spectrum – whether respected, reviled or ridiculed – mullahs are often portrayed as the antithesis of Sufis. Yet in Afghanistan, supposedly the embodiment of all that is wrong with ‘mullah Islam’, there was Haji Saiqal, occupying both roles with relative ease. How was it possible that a mullah, putatively antagonistic to Sufi thought and practice, could become a Sufi leader, the head of a revered and storied khanaqah in the heart of Kabul, taking on the mantle of both esoteric knowledge and protector of the Pahlawan Sufi community?

Sufism and Islam were separated and located within different – and antagonistic – personas

For historians of Islam, Haji Saiqal’s dual position is not so surprising. Many traditional scholars (ulama) throughout history have simultaneously inhabited the role of legal experts and Sufi thinkers, leaders and guides, including al-Ghazali, Abdullah Ansari and Rumi himself. However, at the time when Haji Saiqal was chosen as leader, the changes during Afghanistan’s civil war widened a conceptual rift between what is perceived by many as a Sufi Islam that stands in stark contrast to a legalistic ‘mullah Islam’, a rift that remains to the present day.

The rift has its origins in colonial and Orientalist literature, which divided Islam between a perceived legalistic Islam in contrast to mystic Sufism as an individual, liberal pursuit. One example of this division is the writing of the early colonial envoy Mountstuart Elphinstone (1779-1859), who describes three categories of religious functionaries: the ‘moollahs’, the ‘holy men’ (sayyids, dervishes, faqirs and qalandars) and the ‘Soofees’, whom he considers a minority sect of philosophers. Setting aside the misrepresentation of Sufism as a sect, Elphinstone saw mullahs and Sufis as diametrically opposed enemies in the religious field. Sufism and Islam were separated and located within different roles: the alim who studies the Islamic sciences, in contrast with the Sufi who sees beyond them. Ignoring the reality of a dual orientation of scholar and mystic in a single person, Sufism and Islam were separated and located within different – and antagonistic – personas.

Not only was Islam split in two (legalistic vs mystic), but Sufism was also divided: Sufism as philosophy – the high art and literature of mystic poetry – in contrast to living, contemporary Sufi pirs who were often seen as flawed, or even charlatans. As the anthropologist Katherine Ewing sketched out in 2020 in her overview of the politics of representing Sufism, the living ‘holy men’ were studied and carefully managed by colonial administrators. In contrast, Sufi mystic poetry and literature were to be deciphered by Orientalist scholars. Rather than seeing these various forms as belonging to a varied spectrum of belief, they were located in mutually exclusive roles and personas.

These conceptual splits also played a part in the allocation of religious authority during the decades of war in Afghanistan. Before the onset of the conflict, traditional claims to religious authority were based on religious knowledge, clerical training or Sufi lineages. The problem for Islamist party leaders who rose to prominence during the anti-Soviet jihad was that they lacked all of these credentials. Islamism developed in Afghanistan’s urban university milieu in the 1950s and ’60s, and most leaders of Afghanistan’s emerging Islamist parties, all based across the border in Peshawar, were university-educated men with no traditional religious training or pedigree. Instead, they legitimised their claims to leadership with the fact that they were the first to initiate jihad against the PDPA government in Kabul and had access to weapons and money through the assistance of Pakistan and other foreign powers, including the US and Saudi Arabia.

In an environment of both raw destruction and more fine-grained societal change, in which the external performance of piety was linked either to a position within the war as a mujahidin or as a recognisable authority through title and position, Haji Saiqal proved to be the right man for the moment in two key ways: first, his position and training as a mullah; and, second, his personal pragmatism in dealing with expectations of powerbrokers. His position as a low-level cleric made him recognisable to mujahidin commanders and Taliban officials as a respectable, though nonthreatening, conservative religious scholar, someone whose official position in his mosque they recognised and whose rank would mark him out in a way as ‘one of them’ – a rightful member of religiously legitimated authority. He could face officials when they came for visits to check what was going on at the khanaqah, and he could present an image of respectability by asserting that ritual practices were situated within the strictures of Islamic law.

The neighbourhood mosque that Haji Saiqal led in the Soviet-built neighbourhood of Microrayon seemed to be a physical manifestation of this adeptness at social camouflage. The simple concrete building, rectangular walls, empty halls and plain red carpets were a far cry from the dazzling tiles, arches and impressively constructed domes of Islamic architecture in Central Asia and the Persianate world. I had somehow expected a more outwardly beautified place as the seat of a Sufi leader. But, here, Haji Saiqal did not wear that mantle, donning instead the garb of a humble neighbourhood mullah. The mosque, it turned out, was a repurposed depot and distribution centre where Afghans once came to redeem their food stamps during the PDPA government in the late 1970s and ’80s. Later, it became one of the 94,000 estimated unregistered mosques in Afghanistan. The environment that Haji Saiqal had chosen as his base for teaching and preaching was inconspicuous – one mosque among many, one mullah among hundreds.

The choice of Haji Saiqal as leader of the Pahlawan community was a stroke of navigational genius. The powerbrokers who took control of Kabul in the 1990s – whether mujahidin or later Taliban – were focused on the outward compliance of conduct and representative titles that met their expectations for religious credentials; Haji Saiqal checked all of those boxes. For the Sufi family of the Pahlawan lodge and their followers, however, he was chosen for his character and deeds. They had seen him growing up, from the time when he was a young boy who sometimes joined his father on his visits to the Khanaqah Pahlawan for zikr. This knowledge of Haji Saiqal’s inner state trumped his outward credentials when the community decided to whom to entrust the future of the khanaqah.

Haji Saiqal, the mullah and the pir, becomes a symbol of the creative adaptation

For his part, Haji Saiqal demonstrated a canny ability to manage the volatile environment. He could, when needed, appeal to the Taliban’s morality police from the Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice with his deep knowledge of Sharia. He could just as expertly administer to the needs of the Sufi community. When varying ministers made moves to shut down the Sufi lodge, he drew on his network of madrasa students and their connections to various Taliban officials to keep the doors of the khanaqah open. He led the community into the 21st century, caring for the modernisation of the Sufi lodge in the coming two decades under the coalition governments, until new changes within the governmental set-up were afoot.

When I last visited the Sufi lodge in the winter of 2022, the Taliban had not only taken over Afghanistan, but had also closed all Sufi lodges nationwide after a bomb had struck within another Sufi lodge in Kabul in April – in the same place where Haji Saiqal had originally received his ijaza (authorisation for transmitting knowledge). Not only were the lodges closed but so too were religious foundations in which Sufi scholars were teaching weekly Masnawi classes. The official reason was the same in all instances: the danger of attacks (presumably by the Islamic State’s Afghanistan affiliate, although none of the attacks on Sufi places had been officially claimed by them). One of the Sufi alims in Kabul opined that the Taliban had used the attack as a convenient excuse to close the lodges because they were in reality against Sufism, arguing that, if the Taliban had been concerned for the wellbeing of Sufi affiliates, they would have given the lodges additional security personnel rather than completely shutting them down. After all, why would they want to shut down a place that offered support, spiritual edification, a warm meal and tea, all the manifestation of community self-help at a time when Afghanistan was hard hit by an economic depression and many families were sliding into poverty?

Haji Saiqal would not see these changes – he passed away from a tumour two years before the Taliban took over. Just like in years past, internal transitions within the lodge took place alongside the more overt political changes within Afghanistan. After many deliberations within the community both in Afghanistan and its diaspora, the calm seller of mobile phone cables Haji Tamim, who had been the guardian of the Sufi lodge for decades together with Haji Saiqal, took on the leadership.

The story of how Haji Saiqal and Haji Tamim cared for the Sufi lodge in old Kabul is only one of many. Once we shift our gaze from the capital to other cities, from Kandahar to Herat, Bamiyan to Badakhshan, we find others, maybe not a mullah and a mobile phone-cable seller, maybe this time calligraphers and booksellers, university professors and shopkeepers, who hide books, rebuild community centres and shrines, or who argue with authorities. As the places and persons change, so do their adaptive strategies in dealing with violence and repression. What stays the same is their lives within a centuries-long history of Sufis in Afghanistan, immersed in literature, art, belief, philosophy and worship. Following the Sufi lodge’s trajectory backward in time, through Afghanistan’s recent history of war and instability and the Pahlawan community’s struggles to sustain its traditions, leads us to a place where we begin to see Afghans very differently, not as victims in need of saving but as active agents in preserving Afghanistan’s rich and varied cultural heritage. From this perspective, Haji Saiqal, the mullah and the pir, becomes a symbol of the creative adaptation – an ethos that his successor has taken on as well.

Haji Tamim shrugged when I asked him about the lodge’s closure. ‘The khanaqahs have been here before I was born, and they will exist long after we are gone.’ In his view, governments came and went, but Sufi groups endured – sometimes by simply outliving them, sometimes through engagement and clever navigation. Governments or rulers and their laws could change, but Sufis would not stop gathering.