The likening of cancer to a hostile enemy goes back more than a century. ‘To have a better understanding of the dread thing we know as cancer just compare it with the war,’ wrote Cleveland’s commissioner of health, R H Bishop, Jr, during the First World War. He continued: ‘Prussianism might well be called the cancerous growth that is trying to kill the other nations of Europe, for cancer, of itself, is a lawless growth of body cells which destroys life if allowed to run its course.’

In the early 20th century – when patients were called ‘victims’, long before remissions became tenable for many – the idea of exercising a warlike campaign against cancer gained traction among philanthropists and expert physicians. Yet in their day-to-day lives, people rarely ‘battled’ cancer. For thousands affected, fighting was not an option. Most died within a year or two of a malignant diagnosis. Cancer patients and physicians had little information, scant diagnostic tests, and few medications to consider. For the most part, people with cancer could not be helped except, for the lucky ones, by painkillers.

In today’s more promising climate, a ‘fighting spirit’ appeals to many people with cancer. For some cancer patients I’ve known, it’s been important to say – and for those around them to hear – that they’re trying to summon their emotional and physical powers, to do whatever they can to live longer. Some deploy combative phrases to give themselves pep talks (‘You can beat this’) as encouragement before and while receiving cancer treatment, even though they know full well that the outcome is beyond their control.

Yet hawkish words – talk of ‘battling’, as opposed to, say, ‘coping with’ cancer – have fallen out of favour among physicians, psychologists and patient advocates. As a practising oncologist I avoided that sort of language. War metaphors seemed inapt for describing research or cancer care. And I recognised this risk: if a treatment doesn’t work, if a tumour progresses, patients who have been led to believe that they’re supposed to put up a fight against cancer may blame themselves, mistakenly thinking that they lacked sufficient strength or will, when it’s the treatment that failed.

Whichever way patients and caretakers are inclined to talk about cancer, the history of pugilistic language about the disease could help inform their attitudes. To better understand why fighting words about cancer are commonplace today, and why many experts have moved away from them – concerned about their potential to burden rather than help cancer patients – it’s worth taking a look at their rise to prominence in the United States during the past century, and the debate that followed.

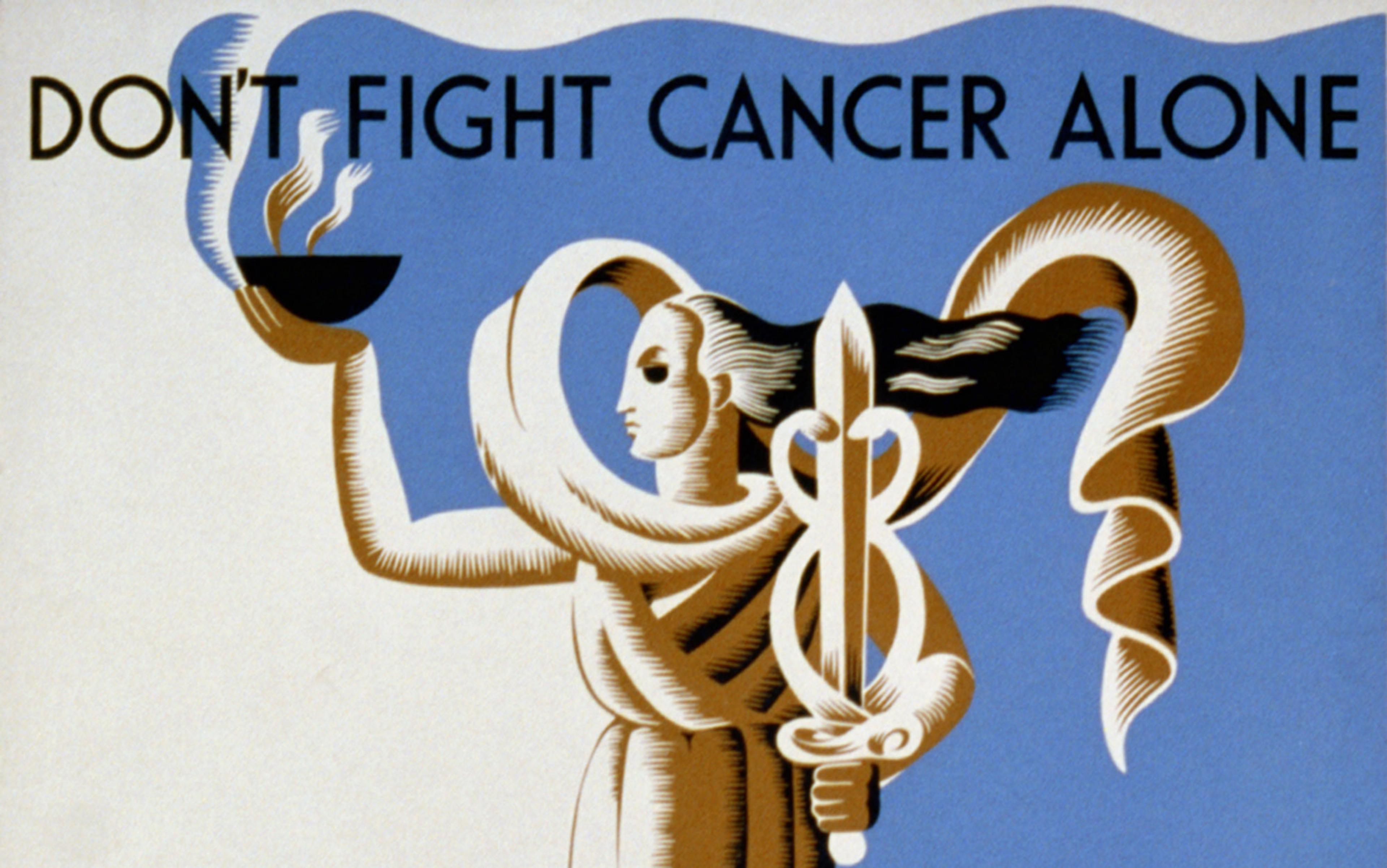

A cancer-slaying sword figures centrally in the image selected by the New York City Cancer Committee as the winner of its 1928 poster contest. Arising from a handle fashioned like a caduceus, the blade appears over the slogan ‘Fight Cancer With Knowledge’. This bold image represented the mission of the New York committee’s parent organisation, the American Society for the Control of Cancer (ASCC), which would eventually become the American Cancer Society. After receiving more than 1,000 entries, the judges of the poster contest awarded first prize and $500 to the Brooklyn artist George E Durant for his illustration. In the decades that followed, the cancer society incorporated the sword in its logo and fundraising themes.

‘Fight Cancer with Knowledge’ poster (c1937). Courtesy the American Society for the Control of Cancer/National Cancer Institute

When US Congress passed and the US president Franklin Roosevelt signed legislation establishing the National Cancer Institute in 1937, a Washington Post headline announced: ‘“Conquer Cancer” Adopted As Battle Cry Of The Public Health Service’, capturing the prevailing sentiment that defeating cancer warranted a warlike effort. The newest branch of the US Public Health Service would counter malignancy on two fronts, the paper reported. Researchers at the institute would investigate cancer’s causes and possible cures, while practising physicians would extend established treatments to regions where medical knowledge and facilities were limited.

At the time, most people with cancer sought legitimate medical care only after the disease had spread, if they did so at all. Fearing ‘the knife’, many patients delayed surgical consultation until it was too late. In the absence of effective medicines to treat cancer, quacks selling bogus ‘cures’ flourished.

As another world war loomed, the Women’s Field Army dug into military rhetoric

Against this backdrop, the mantra ‘Fight Cancer With Knowledge’ referred not to cancer biology or laboratory investigations, but to the public’s understanding of disease and its proper treatments. Medical research, as we know it, was in its infancy and for the most part was not a priority for the ASCC until after the Second World War. Rather, the organisation aimed to educate people about cancer so that cases might be caught early, when established remedies – predominantly surgery and radiation – might be curative. ‘Do Not Delay’ was another go-to phrase. Experts affiliated with the cancer society emphasised that defence against malignancy rested in the public’s knowledge that cancer could be cured if treated promptly, in the recognition of symptoms (‘danger signals’), and in familiarity with appropriate care.

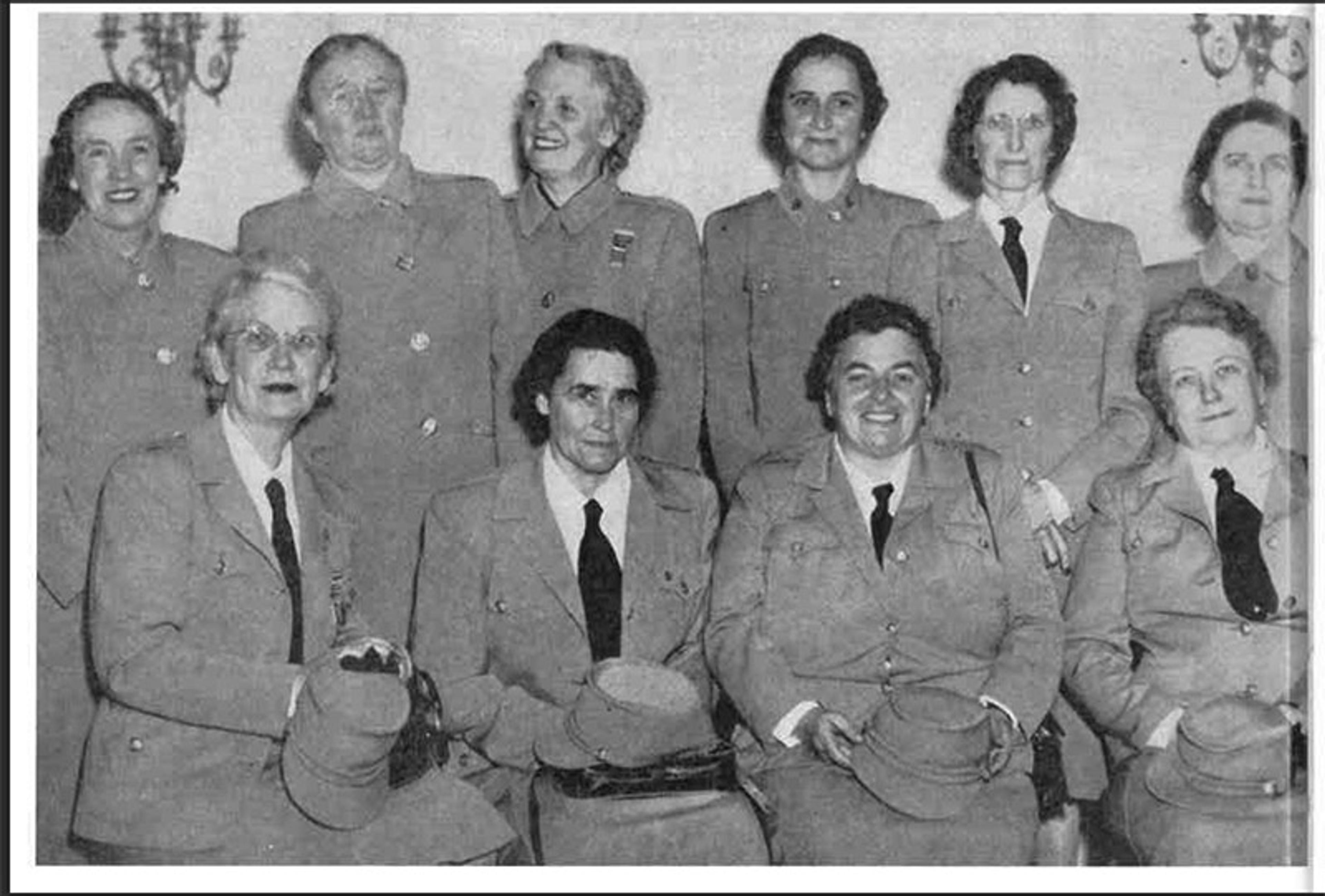

In pursuit of its mission, the ASCC sponsored the Women’s Field Army (WFA), a military-styled, grass-roots organisation that distributed anticancer literature and raised funds for the society. By 1939, led by its formidable national commander Marjorie Illig, the women’s network involved legions of territory-level, state and city commanders, deputy and vice commanders, adjutants, and majors who supervised captains, lieutenants, sergeants, corporals, and several hundred thousand ‘troops’. Each ‘recruit’ was expected to pay a $1 enlistment fee to support the cause.

As another world war loomed, the WFA dug into military rhetoric. In February 1938, for instance, Illig spoke with the US Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers in a radio segment titled ‘Women, Enlist, This Is Your War’. Mentioning the ongoing conflicts in Spain and China, Illig said:

Our war is of a very different kind… We are not using bayonets or tanks or machine guns: our weapons are leaflets and lectures. We are fighting with facts and our military objectives are the putting to rout of fear and ignorance.

As if they were at war, WFA regional commanders wore drab brown uniforms.

National WFA commander Marjorie Illig (seated, third from left) with regional commanders in uniform, 1942. Courtesy the American Cancer Society

The battle metaphor stuck. From the late 1940s onward, the American Cancer Society’s annual ‘cancer crusade’ – emblemised by the sword – delivered millions in donations. As scientists sought to develop radioactive compounds for cancer therapy, newspapers trumpeted those efforts with headlines like ‘Hospital Dedicates Atom “Bomb” To Fight Cancer’. Readers absorbed the metaphor from stories such as ‘The Long, Slow Battle With Cancer’ (1952) in Harper’s Magazine and ‘New Weapons Against Breast Cancer’ (1962) in Ladies’ Home Journal.

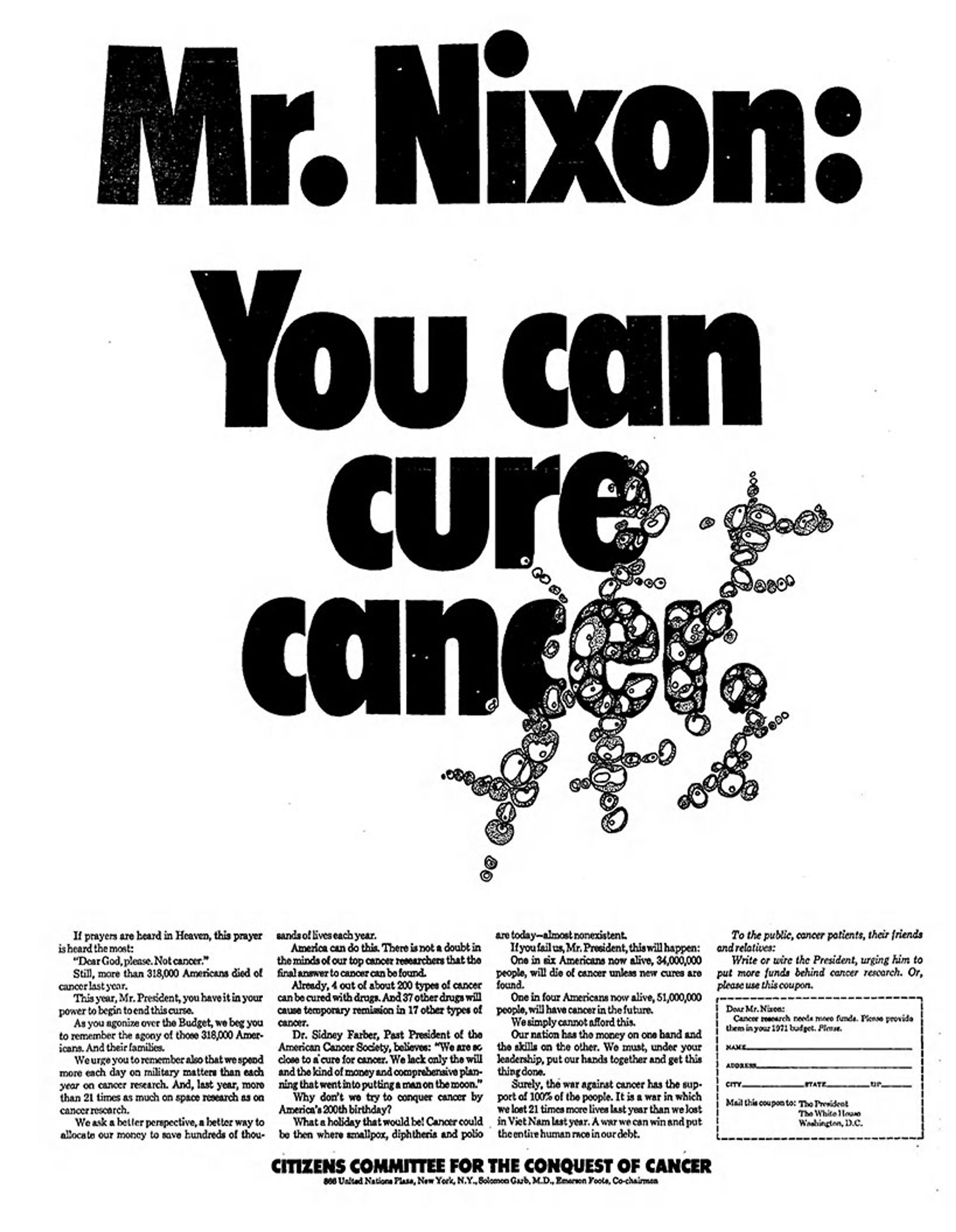

The phrase ‘War on Cancer’ is often attributed to the US president Richard Nixon in connection with his signing of the National Cancer Act of 1971, although the expression antedates that by decades. Speaking at a White House ceremony in December 1971, the president compared US deaths from cancer with those lost in another war: ‘We find that more people each year die of cancer in the United States than all the Americans who lost their lives in World War Two.’ Nixon hoped the Christmastime announcement would divert public attention from the real, ongoing war in Vietnam.

Figurative thinking about illness clouds patients’ rationality, argued Susan Sontag

While few at the time objected to invoking war images when discussing cancer, the writer Lucy Eisenberg wrote an article that year for Harper’s that was subtitled: ‘Guerrilla action or massive assault – which strategy for the war against cancer?’ Scientists were silently opposed to the ‘Conquest of Cancer’ legislation moving through Congress in 1971, she wrote, adding:

Its proponents, who are mostly laymen, claim that breakthroughs in cancer are imminent, and that given enough money and the proper management techniques, man can conquer cancer just as he split the atom and landed on the moon. But scientists themselves dispute this assumption.

Eisenberg questioned why US Congress would implement a ‘crash program[me]’– speeding the pace of federal cancer research rather than providing steadier and potentially less wasteful support for basic investigations – and answered:

Congress was bewitched by words. Whipped into a rhetorical frenzy with talk of ‘universal anguish and suffering’ and of ‘overcoming an implacable foe’, it overlooked the great areas of ignorance about cancer that still remain.

‘War on Cancer’ criticisms mounted after 1975, when the Columbia Journalism Review published a takedown by Daniel S Greenberg, a medical journalist. ‘With the acceleration of the so-called federal War on Cancer, now in its third year,’ the article began, ‘it is useful to contemplate certain curious and gruesome parallels that are beginning to appear between the reporting of this “war” and the early bulletins from Vietnam.’ Contrary to favourable statistics and upbeat reports distributed by the American Cancer Society, progress against cancer was slim and mainly attributable to surgical advances made before 1955, Greenberg maintained. Cancer research, while costing the government enormous sums, ‘has its own politics, vested interests, warring factions, and public-information apparatus’, he stated.

A 1969 Washington Post appeal from the Citizens Committee for the Conquest of Cancer. Courtesy the National Library of Medicine

Nonetheless, the language of war remained popular well beyond 1978, when Susan Sontag decried it in her book Illness as Metaphor. Sontag had recently completed aggressive breast cancer treatments: a radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, and an experimental immune therapy. Figurative thinking about illness clouds patients’ rationality, she argued. Perceiving cancer as a demonic enemy supports ‘avowedly brutal notions of treatment’, she wrote, adding that if the patient’s body is ‘considered to be under attack (“invasion”), the only treatment is counterattack.’

Alluding to Greenberg’s perspective, Sontag wrote:

It is one thing to be sceptical about the rhetoric that surrounds cancer, another to give support to many uninformed doctors who insist that no significant progress in treatment has been made.

The truth about cancer lay between the ‘twin distortions’ of military rhetoric – the US cancer establishment’s ‘tirelessly hailing the imminent victory over cancer’, and the pessimistic specialists who talked ‘like battle-weary officers’.

Other influential people who’d been cancer patients embraced the language of war, finding it empowering. The Black feminist and poet Audre Lorde was explicit in her desire to be seen as a combatant against cancer: ‘Women with breast cancer are warriors,’ she wrote in The Cancer Journals (1980) after undergoing mastectomy in the late 1970s. Lorde rejected pressure to wear a breast prosthesis after surgery. In her community, cancer was often hidden. Rendering wounds invisible isolates and disempowers cancer patients, she asserted. Lorde compared her postmastectomy figure with Moshe Dayan, the Israeli leader who wore an eyepatch over his empty eye socket, a war wound. ‘Nobody tells him to go get a glass eye … The world sees him as a warrior with an honourable wound,’ she wrote. ‘I refuse to have my scars hidden or trivialised behind lambswool or silicone gel. I refuse to be reduced in my own eyes or in the eyes of others from warrior to mere victim.’

Lorde’s words foreshadowed the ‘silence = death’ message popularised by people with AIDS a few years later. She wrote:

If we are to translate the silence surrounding breast cancer into language and action against this scourge, then the first step is that women with mastectomies become visible to each other. For silence and invisibility go hand in hand with powerlessness.

Indeed, after public demonstrations by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), some cancer patient advocates became activists, realising that they needed to fight for faster research, better care and access to treatments.

‘Some people are going to die, no matter what they do. But … if a person doesn’t try, there is no way they can beat it’

In the 1980s, ‘battling’ cancer came to suggest a daringly active role for patients – that they didn’t have to suffer passively, that their knowledge and choices could make a difference. When Richard Bloch, a cofounder of the tax company H & R Block, was first diagnosed with lung cancer, doctors said that his condition was hopeless. He then consulted a specialist at Houston’s MD Anderson Hospital and was fortunate; after surgery, he survived for more than two decades. Bloch coauthored a book, Fighting Cancer (1985), sponsored an information hotline, and started a foundation to help others who were affected. He encouraged all cancer patients to seek second opinions before ‘giving up’.

In Bloch’s view, fighting cancer involved information-seeking. As some physicians didn’t keep up to date in their knowledge, they’d recommend that people with cancer ‘go home and make themselves as comfortable as possible’, Bloch observed. ‘I’m not saying that everyone can beat cancer,’ he clarified. ‘Certainly, some people are going to die from it, no matter what they do. But … if a person doesn’t try, there is no way they can beat it.’

The comedian Gilda Radner, another prominent cancer fighter of this era, received gruelling chemotherapy for ovarian cancer before she died at age 42. Before Life magazine put Radner on a cover in 1988, editors sent her a photograph. ‘It looked like “coping with cancer” to me,’ she shared in her memoir, It’s Always Something (1989). ‘I didn’t want a “coping with cancer” cover because that’s not the way I was dealing with cancer,’ she wrote. ‘I wasn’t coping, I was fighting.’

Many doctors have objected to the use of military words in the context of illness due to the potential psychological ramifications. A person’s lack of responsiveness to cancer treatment, a relapse or death could erroneously suggest that they didn’t try hard enough, that they were ‘weak’ and somehow responsible for succumbing to their illness. A patient’s loved ones may blame them, consciously or not, if they fare poorly after a cancer diagnosis. Patients may even blame themselves.

Few clinical studies have examined the possibility of a relationship between cancer patients’ attitudes and their survival with any scientific rigour. In June 1985, the New England Journal of Medicine published a prospective analysis of several hundred cancer patients, conducted by the sociologist Barrie Cassileth and her colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center. In people with cancer, ‘the biology of the disease appears to predominate’ and ‘override the potential influence of lifestyle and psychosocial variables’ such as hopelessness, they concluded. In an editorial citing that study, Marcia Angell criticised popular notions about psychological causes of cancer and its progression, writing: ‘A view that attaches credit to patients for controlling their disease also implies blame for the progression of the disease.’ The editorial generated an enormous response, with pushback in published letters.

Journalists stirred the debate. In October 1985, The New York Times ran two articles about the controversy by Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and author, who wrote in that paper’s science section:

Some researchers are concluding that breast cancer patients, for example, who are openly upset and show a fighting spirit – ‘I’m going to conquer this thing!’ – marshal stronger immune defences against the spread of the disease and are more likely to survive than those who suffer with quiet stoicism.

His pieces drew the attention of Jimmie Holland, head of the psychiatry division at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and the psychologist Morton Bard. A month later, in a letter to the Times, Holland and Bard stated:

[P]atients with cancer are bombarded with information that ‘bad’ attitudes hasten death, and ‘good’ attitudes (sometimes hard to sustain when feeling ill) must be maintained to control disease. A fighting spirit and optimism contribute to wellbeing, to a sense of control of the situation … On the other hand, patients in whom cancer progresses seem to be blamed for not trying hard enough. This follows the well-known ideology, applied to such problems as poverty and crime, of blaming the victim when no explanation can be found.

Holland, who dedicated her career to the field of psycho-oncology, spoke of the ‘tyranny of positive thinking’. Years later, she said in an interview with CBS: ‘The idea that we can control illness and death with our minds appeals to our deepest yearnings, but it just isn’t so.’

‘The use of the battle metaphor implies a level of control that patients simply do not have’

The issue simmered. In 1999, The Lancet reported some evidence that women with early stage breast cancer who experienced depression or scored highly on a scale measuring ‘helplessness and hopelessness’ were more likely to die within five years. Other studies, while limited, have not supported a connection between psychology and survival. Researchers with the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, led by the psychologist James Coyne, surveyed more than 1,000 patients with head and neck cancers to study whether their emotional states, such as sadness, might affect medical outcomes. In an analysis published in 2007 by the journal Cancer, Coyne and colleagues found no relationship between cancer patients’ survival and emotional wellbeing. ‘The belief that emotional wellbeing affects survival, nonetheless, has been remarkably resilient in the face of contrary data,’ they wrote.

Doctors today generally caution against framing malignancy as an enemy that one must personally defeat. ‘The use of the battle metaphor implies a level of control that patients simply do not have,’ wrote the physicians Lee Ellis and Charles Blanke, and the cancer survivor and patient advocate Nancy Roach in a 2015 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association:

[W]hen we talk about the ‘battle’, we minimise the real issues faced by patients every day. Patients deal with and sometimes overcome nausea, pain, fatigue, and weight loss. They suffer the isolation that comes with a diagnosis. For those with potential curative disease, they live with the fear of recurrence and impact of chronic adverse effects.

The ‘continuous urge to win the battle’ may extend to physicians, they noted. Oncologists’ desire for ‘victory’ over cancer may be detrimental to their patients if they’re inclined to prescribe inappropriately aggressive treatments. And patients, wishing to ‘beat’ cancer, may be reluctant to accept palliative or hospice care.

As a physician, I know there is no such thing as a tumoricidal mindset. My preference is to avoid battle language. But if someone else wants to say they’re fighting their disease, maybe that’s OK – so long as they and their doctors are clear-eyed about it, and they don’t deceive themselves into thinking they might control their outcome with an upbeat attitude or thoughts. Cancer patients have different styles and ‘philosophies’. What’s hurtful to one may be helpful to another.

Some years ago, while engaged as a journalist, I was invited to a fundraising event – a ‘Haymakers for Hope’ amateur boxing match – at Madison Square Garden. I’d never been to a boxing event or watched one on TV, for the violence of it. But I was drawn to the symbolism: the participants would be fighting, literally, for cancer charities of their choice. They’d been training, working out for months, to punch and knock each other out for a dear cause. Unsure if I could handle it, I contemplated Leslie Jamison’s book The Empathy Exams (2014), in which the author challenges herself, her empathy, by meeting people with behaviours and beliefs that differ from hers. At the event, I interviewed boxers who had lost friends to the disease. The ‘ring girls’, as they were called, were cancer survivors. Who was I to be critical?

Progress against cancer has mounted in recent decades. Whether that is attributable to the federally funded ‘War on Cancer’ launched during the Nixon administration or to the steady and incremental work of scientists over the past half-century (involving governmental, philanthropic and corporate investment that might have happened anyway), or both, is impossible to know. But the gains are undeniable. In 1975, the overall US death rate from cancers was 199 per 100,000; this rate rose until 1991, when it peaked at 215, and has since fallen steadily to 144 per 100,000 of the population overall in 2020 – a decline of 28 per cent since 1975. The US Cancer Moonshot programme, initiated in 2016, promises to support further advances. Yet some, such as Jeffrey Kluger at Time magazine, have criticised this approach, likening it to the ‘War on Cancer’.

Today, as better diagnostic tools, immune agents and targeted cancer therapies are becoming available, the most important thing is what we actually do, at the societal level, to help people with cancer. The question is if we’re willing to fund an all-out effort to help those affected through more inclusive research and provision of care. And here is where aggressive metaphors might be most appropriate: now that cures may be possible, it’ll take a political fight to lower cancer drug prices and assure that all patients have equal access to the treatments they need.