To connect Shinto to any form of ‘universal religion’ would appear to be a fool’s errand. After all, as any guidebook to Japan will tell you, Shinto is the traditional religion of Japan and only Japan, apart from a scattering of Shinto shrines in countries with large Japanese immigrant or expatriate populations.

At the same time, Shinto is considered to be, at least in its origins, one expression of animism, the world’s oldest religion. Thus, we are left with Shinto as both a religion unique to Japan and an expression of the world’s oldest faith.

The word animism is derived from anima in Latin, which literally means ‘breath’, with an extended meaning of ‘spirit’ or ‘soul’. Animism recognises the potential of all objects – animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather-related phenomena, deceased human beings, even words – to be animated and alive, possessing distinctive spirits. As such, animism is considered to contain the oldest spiritual and supernatural perspectives in the world, dating back to the Palaeolithic Age when humans were still hunter-gatherers.

Viewed from the standpoint of today’s organised religions, animistic religions can seem ‘primitive’ and are often dismissed as containing nothing more than superstitious beliefs and practices. This belittling if not antagonistic attitude toward animism has been particularly strong among the Abrahamic faiths – Judaism, Christianity and Islam. For example, in the United States it was not until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1978 that indigenous peoples gained the legal right to practise their traditional animistic faiths.

Given this, as one of the world’s last still-flourishing animistic faiths, Shinto can provide a gateway to better understanding the origins of certain universal paradigms found in today’s organised religions.

A Shinto shrine can reveal how remnants of ancient animistic practices, as embodied in contemporary Shinto, can survive in the organised religions of the contemporary world. However, today’s Shinto should not be confused with ‘State Shinto’ (or kokka-shintō in Japanese). The latter was a 19th-century political programme created by the Japanese government to effect national unity and obedience by promoting the divinity of the emperor, a programme that existed right up until Japan’s defeat in the Second World War.

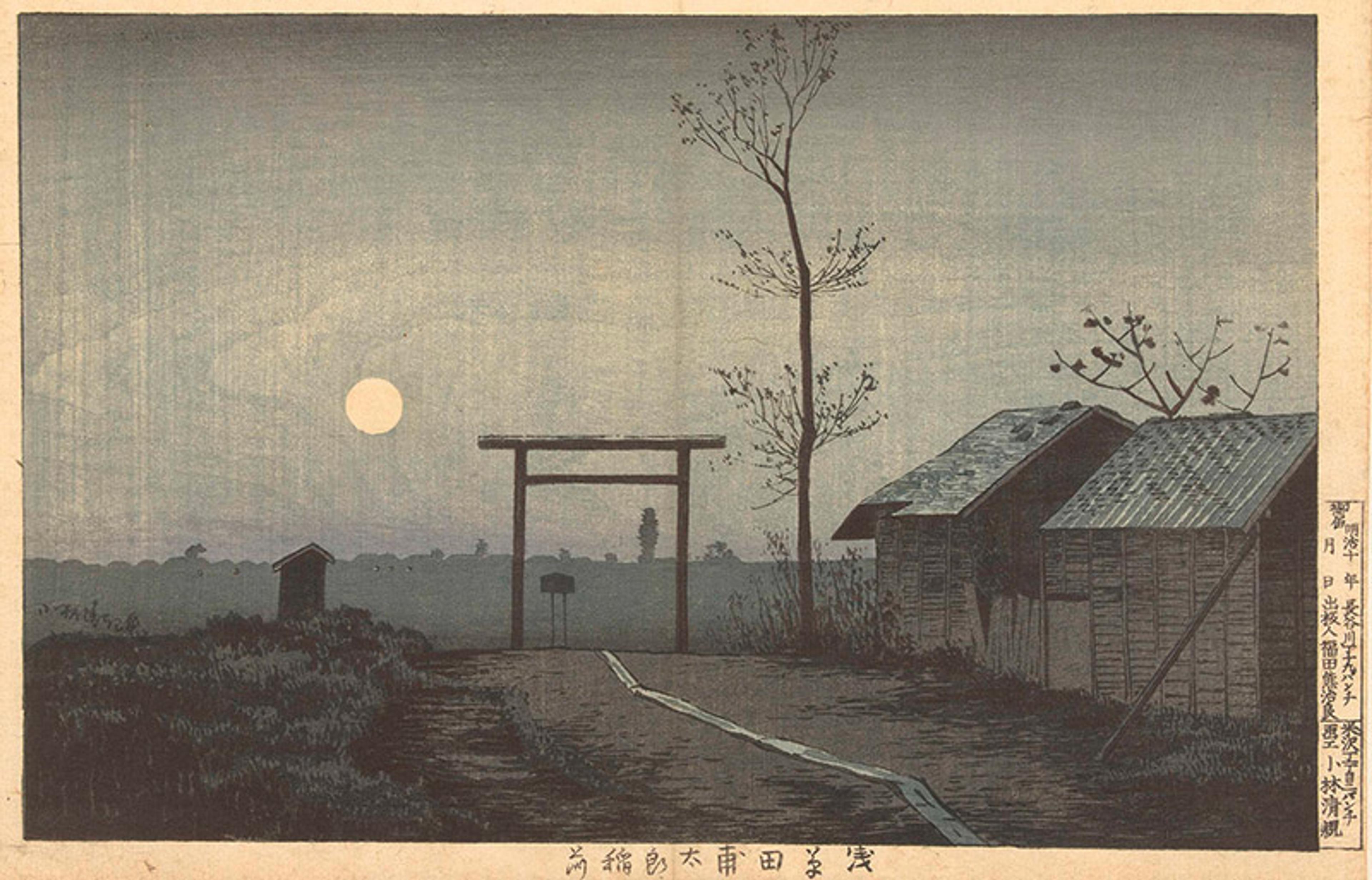

The Taro Inari Shrine in the rice fields at Asakusa, by Kobayashi Kiyochika, 1877-1882. Courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

On entering a Shinto shrine area, the initial ritual practice is the cleansing of one’s hands and mouth. This is an abbreviated version of the full-body immersion that continues to be practised in Shinto, typically by standing under a waterfall. In both instances, flowing water is recognised not only as a physical cleansing agent but as a spiritual one as well. To be clean in body and mind is required prior to approaching Shinto deities known as kami. Shinto is, of course, not alone in viewing water as a spiritual cleansing agent.

Remnants of this Shinto practice can be seen in the use of ‘holy water’ upon entering a Roman Catholic church, or the partial and whole-body immersion during baptism, which is practised by nearly all Christian denominations. Muslims meanwhile engage in the ritual cleansing of exposed body parts – hands, face and feet – prior to entering a mosque. And in Judaism, a mikveh is a bath used for ritual immersion in order to achieve spiritual purity.

Once ritually cleansed, the Shinto practitioner approaches one or more kami, typically to offer a petitionary prayer. However, prior to seeking the kami’s blessings, practitioners are expected to make an offering, traditionally such things as food, sake or even a fine horse, but today more typically money. In other words, to ensure the kami’s blessings, the practitioner must first engage in a transactional relationship with the deity being worshipped.

Of all the ways that animistic practices might have been incorporated into organised religions, this transactional relationship is potentially the most far-reaching. Simply stated, there is no organised religion existing today that does not, directly or indirectly, require the believer to make an offering of some kind as a necessary condition for receiving the deity’s blessings, as well as in order to be accepted among the faithful.

Shinto conducts purification rituals on cars, personal computers and construction sites for skyscrapers

Even today, there are Orthodox Jews who intend to resume the traditional practice of killing blemish-free animals as ‘burnt offerings to the Lord’ once the Third Temple is rebuilt on Temple Mount in Jerusalem. While the meaning of these burnt offerings might have changed over the millennia, their origins seem clear. And just as in today’s Shinto, the typical offerings to the deity (or deities) of all organised religions are now in the form of decidedly unburnt currency.

Shinto, too, has its own form of burnt offering. Instead of a slain animal, however, a collection of wooden sticks is ritually burned in a ‘holy fire’. The Shinto practitioner first writes his name, age and gender on one side of the stick before writing his personal wish on the stick’s other side. Of course, the practitioner is expected to make a financial donation to the shrine to ensure that his wish is fulfilled as it rises to the heavens in the form of smoke. Anthropologists suggest that the ritual offering of a precious object to a deity might be the oldest form of religious practice known to Homo sapiens.

Today, believers of all organised religions continue to pray to the deity (or deities) of their faith for multiple blessings – for example, abundant harvests, water in times of drought, etc. The ‘tribal’ or collective nature of these prayers appears little-changed over a period of tens of thousands of years. At the same time, requests for personal blessings – for good health, wealth, etc – are now commonly found in all faiths. Nevertheless, nationalistic or tribalistic calls such as ‘God Bless America’ (instead of ‘all nations’ or ‘all peoples’) still reverberate from the mouths of political and religious leaders of many countries.

Given the tribal origins of animistic faiths, it is not surprising that few tribal or ethnic outsiders have ever been allowed to become clerics. In Japan’s case, it was not until 2014 that the Austrian Florian Wiltschko became the first non-Japanese person to receive an official licence allowing him to become a full-time Shinto priest working at a shrine in Tokyo. This development suggests that Shinto might be beginning the transition to a more universal faith.

While there is a tendency to regard animistic faiths as either primitive or at least stuck in the past, Shinto belies this reputation. Not only does it accept foreign priests but it also, for example, conducts purification rituals on cars, to ensure the traffic safety of adherents. Moreover, it is even possible to bring personal computers to the shrine for ritual purification. This is in addition to more traditional purification rituals such as those performed at ground-breaking ceremonies at construction sites, whether for private residences or soaring skyscrapers. Albeit an animistic religion, Shinto is clearly capable of evolving and remaining relevant to the modern world. This flexibility and openness are no doubt one of the main reasons for its ongoing vitality.

Like all animistic faiths, Shinto is polytheistic in nature. While polytheism might seem to be an artifact of primitive religion, it is important to remember that polytheism and monotheism share three essential traits. First, they are both ‘theistic’ – they share a common belief in the existence of an unseen spiritual being (or beings). The difference, albeit an important one, is whether there is one or many such beings.

Second is the belief that the object (or objects) of worship are capable of conferring blessings of various kinds on their believers. The distinguishing feature is, of course, whether one deity offers multiple blessings, or multiple deities offer multiple blessings. The crucial belief they share in common is the possibility of multiple blessings. Moreover, these blessings can be enjoyed by both the individual as well as the community of believers, originally the tribe and, today, the nation.

Third, although there are now a few exceptions, the deity (or deities) in organised religions, like their animistic counterparts, continue to have gender: male or female. The Sun Goddess Amaterasu is a central Shinto deity. Her younger and powerful brother Susano-o is the god of the sea and storms. In Christianity, by comparison, God has traditionally been portrayed as male, though some adherents today prefer to use the pronoun ‘she’. At the same time, there are few if any who refer to God as an ‘it’. Psychologically at least, a transactional, or interpersonal, relationship with a non-gendered ‘it’ is difficult if not impossible to imagine.

Similarly, both monotheistic and polytheistic deities share the personality traits of ordinary human beings. The monotheistic deity, for example, is often described as being capable of becoming ‘angry’ and ‘jealous’ in the face of disrespect or wrongdoing, yet is equally a ‘God of love’ or ‘loving Father’ toward those adherents who act according to His wishes. For this reason, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the God of monotheism retains many of the personal characteristics of animistic predecessors, albeit at a transcendent level.

It is possible to see in shamans the prototype of religious leaders of all faiths

Another common feature of Shinto is that of shrine maidens or miko. Today, shrine maidens typically sit at reception counters selling such things as amulets or personal fortunes, but they also perform sacred dances known as kagura. Kagura performances suggest the critically important role that miko once played in Shinto, for these sacred dances are originally derived from ritual dances in which miko channelled the kami, speaking, singing and dancing as if they were the deity. In other words, miko were once shamanic diviners who, having been taken possession of by a kami, could convey the deity’s will or provide a divine revelation in the form of an oracle. Thus, they played the crucial role of go-between with the spiritual world.

A shrine maiden at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo in October 2012. Photo by Kazuhiro Nogi/Getty

In Japan, the position of shaman was typically, though not always, passed down from generation to generation. An acknowledged elder shaman, who might be a family member such as an aunt, would teach the girl in training how to control her trance state during dancing. It was also important that she learned how to communicate with multiple kami as well as the spirits of the deceased. All this was done to ensure the kamis’ blessings on the people and, equally, to protect them from malevolent spirits. Serving as intermediaries between gods and ordinary believers, it is possible to see in shamans, both male and female, the prototype of religious leaders of all faiths, whether they are now referred to as imams, priests, pastors, rabbis, etc.

Two of the most important oracles in Japanese history concern the relationship of kamis to the Buddhist faith when it was first introduced to Japan in the mid-6th century. When the Great Buddha of Nara’s Todai-ji temple was completed in 749 CE, the Shinto god of war Hachiman – enshrined in the Usa Shrine on the southern island of Kyushu – issued an oracle that he wished to come to pay homage to the Great Buddha. A shrine maiden transported Hachiman to Todai-ji where he was installed as the temple’s official protector. This subsequently led to various Shinto kami being incorporated as protectors of Buddhist temples throughout the country. Even today, one can see these guardian deities honoured with small Shinto shrines located on temple grounds.

A second and still more important oracle involved the Ise Shrine, home of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. Tradition states that messengers were sent to Ise to secure approval of the Sun Goddess for construction of the statue of the Great Buddha. The particular Buddha chosen to be placed in the cathedral was known as Vairochana in Sanskrit, or Dainichi in Japanese, ie the Sun Buddha. The answer of the Ise oracle seemed to indicate that the Sun Buddha was identical to the Sun Goddess. Conveniently, this identification also enhanced the status of the emperor for, as the mythological descendent of the Sun Goddess, he was now directly related to an even more powerful personage, the Sun Buddha, believed to possess magical powers.

There was, however, a downside to the Buddhist acceptance of Shinto deities, for it was the Shinto deities who were relegated to the role of protecting Buddhist temples, not the other way around. Their role as protectors was justified on the basis that, just like all sentient beings, kami were suffering creatures seeking to escape their present condition and attain Enlightenment. Buddhist priests created a series of tales describing the desire of various kami to receive the Buddhist teachings, thereby overcoming the negative karma that had caused them to remain as no more than deities. Some kami, it was claimed, even expressed their desire to become Buddhists by taking refuge in the Three Treasures – Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

In the following centuries, Shinto clergy accepted what was essentially second-class status for themselves and their deities. This included Buddhist control of major Shinto shrines as embodied in the construction of jingu-ji (shrine-temples), built with the encouragement of the government. At these shrine-temples, Buddhist priests recited Buddhist sutras for the sake of the kami who had, it was claimed, decided to protect the foreign faith in hopes of spiritual advancement.

This development helps to explain why, when Shintoists finally had the opportunity to free themselves from Buddhist control at the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, they eagerly did so. Although, as noted above, ‘State Shinto’ was a political construct of the new national government, Shinto leaders nevertheless welcomed this development, for at long last Shinto could be independent. However, the cost of this independence was that Shinto leaders were expected to support the policies of the Japanese government without question.

As Japan expanded and became an empire in the 1900s, Shinto also became an important spiritual support mechanism for justifying Japanese expansion. This might be considered the Achilles’ heel of not just Shinto but all animistic faiths, for they are easily captured by the tribal or ethnic zeitgeist, especially in wartime. Thus, Shinto leaders readily supported the political policies of their ethnic leaders, no matter how aggressive those policies were. With Shinto’s blessing, Japan came to be regarded as a divine land, protected by kami, and ruled over by a divine emperor who was himself, according to Shinto mythology, a descendant of the Sun Goddess.

On the one hand, none of the preceding provides a rationale for embracing animistic-based faiths such as today’s Shinto. But nor is there any justification for attempting to suppress animistic faiths, other than when they become the handmaidens of repressive governments. They remain the living expression of the once-universal spiritual heritage of all Homo sapiens.

None of this commentary is meant to deny the authenticity of any religious faith, past or present. The world’s major religions would not have endured for thousands of years if they failed to meet the spiritual needs of millions of their followers. Yet it is sobering, if not humbling, to consider how deeply today’s organised religions are indebted to their animistic antecedents. In fact, the acceptance of other deities, regardless of one’s own personal belief, forms the very foundation of what has become, in a globalised world, the widely accepted ideal of religious tolerance. And religious tolerance is a value that remains in all-too-short supply, even today.