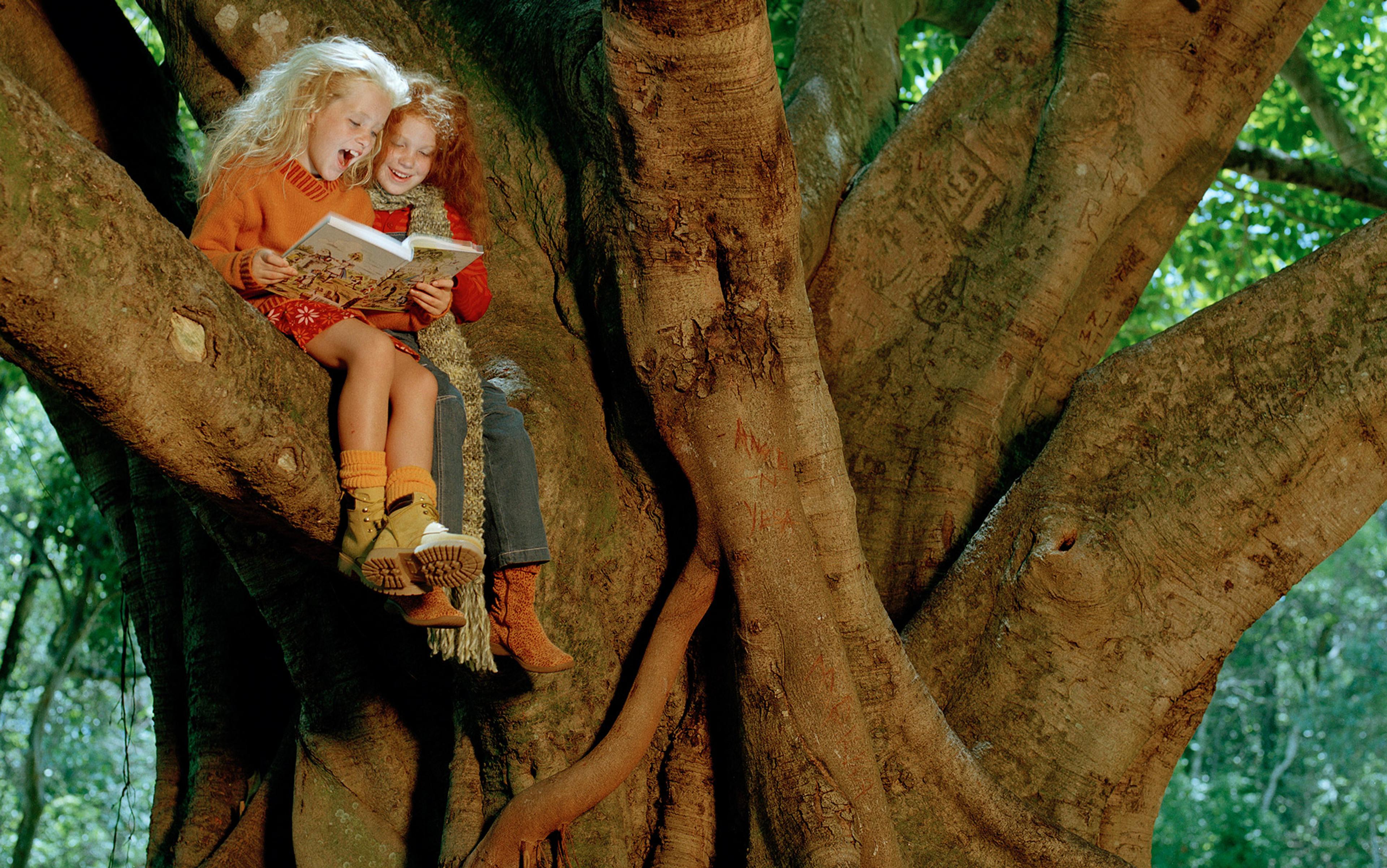

Almost six years ago, when I became a parent, one of my very few certainties was that I would read to my daughter. I had been an only child, and now I was raising one. I wanted my daughter to learn, as I had, that stories were sources of adventure, inspiration and constant, loyal companionship.

So I read to my daughter the way I had been read to, eclectically but faithfully. As she got older, we talked about the exploits of Frog and Toad, and Junie B Jones, and the Pevensies almost as often as we talked about her friends from school. As soon as she could write the letters of her name, she got her own library card and started to add her selections to the pile. And last year, when we started to read J R R Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit (1937) together, she listened patiently to the first two chapters. Then she told me, matter-of-factly, that Bilbo Baggins was a girl.

Well, I said. That would be nice. But Bilbo is definitely a boy.

No, she said. Bilbo is a girl.

I hesitated. I wanted to share the story I knew, and I had always known Bilbo as a boy. But it seemed that my daughter knew otherwise. I soon agreed to swap ‘she’ with ‘he’ and ‘her’ with ‘his’, and my daughter and I met Girl Bilbo – who turned out to be a delightful heroine. She was humble and resourceful and witty and brave. She was no tacked-on Strong Female Character with little to do, but a true heroine with her very own quest and skills. For my daughter, Girl Bilbo was thrilling. For me, she was damn refreshing.

When I wrote about this experiment in literary gender-swapping for the Last Word On Nothing website last year, the public response to Girl Bilbo was startling. My daughter had ‘brought the internet’s Tolkien fanboys to their Mithril-padded knees’, in the words of one commenter. Girl Bilbo and her implications, I knew through comments and emails, were discussed at length in science-fiction circles, parenting groups, Head Start classes, and among Swedish devotees of role-playing games.

While many of these readers were enthusiastic about my daughter’s idea, a sizable minority thought I was indulging heresy. Leave the classics alone, they said. If you want stories with more female characters, some suggested, write them yourself. But my daughter didn’t create Girl Bilbo, and neither did I. She has deep roots, and she isn’t going away anytime soon.

I remember the moment I learned that books were imperfect. I was a teenager – 14 or 15, maybe – and I was in my school library, searching for books for a research paper. My English teacher appeared at my elbow with a hardcover in hand. ‘It’s not a very good book,’ he said, pushing it toward me, ‘but it’ll have some useful information.’

I stared at him. A book could be… something other than good? I’d been transported by books since childhood, and it had never occurred to me that they could have flaws. I knew I liked some stories more than others, but that was just personal taste. I had only a vague idea of how books were written and published, and I assumed that whoever or whatever oversaw that process was as wise as Gandalf. The words that lay between the covers of books were, as far as I was concerned, perfect.

Decades later, I’m still full of respect for the hard work that goes into writing any kind of book, fiction or non-fiction. As a writer myself, I recognise the importance of books as neat, marketable packages by which writers can learn a living.

I also know that books are fallible. I know the publishing industry is made up of people who love good books yet profit from bad ones. And, like most writers, I know that even the best books – the books that stay with us for a lifetime, the books that are read and re-read by people of different ages and different generations – are not sovereign objects, no matter how hefty their covers. ‘All novels are sequels; influence is bliss,’ wrote Michael Chabon in his essay collection Maps and Legends (2008). Every writer, no matter how fresh his or her vision, draws inspiration and ideas from the work of those who came before.

Likewise, every story – fiction or non-fiction – leaves room for the next writer, the next era, the next leap of imagination or understanding. ‘When we tell a story, we exercise control, but in such a way to leave a gap, an opening,’ wrote the English novelist Jeanette Winterson in her memoir Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (2011). ‘It is a version, but never the final one. And perhaps we hope that the silences will be heard by someone else, and the story can continue, can be retold.’

We have, of course, been telling and retelling stories for at least as long as we’ve had campfires. For millennia, writing had no part in storytelling, and was sometimes even considered a threat to it. Plato worried that writing would remove the need for memorisation and so ‘create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls’.

In the mid-1400s, when the German inventor Johannes Gutenberg arranged metal type on the business end of a wine press, he not only introduced printing to Europe but also democratised the written word. You know the story: thanks to the printing press, literacy flowered, Latin withered, and a middle class rose throughout the continent.

Yet recently the scholars Thomas Pettitt and Lars Ole Sauerberg of the University of Southern Denmark have suggested that the printing press had another, less-recognised effect. Even as it dismantled old hierarchies, it gave new and far-reaching authority to printed books – and to their authors.

To be sure, written texts existed long before Gutenberg, and in many different cultures. But in Europe before the printing press, Pettitt argues, storytellers most often performed their stories. Like folk singers, they drew from existing material and reshaped it as they wished. However, as books became more widely available, texts gained value as standard, stable, and more or less original units of knowledge. Humanity’s long wave of stories now had a particle form, too.

Were the Brontës growing up today, their zine would circulate far beyond the family parsonage

William Shakespeare, who wrote in the midst of this transition, was both revered and criticised for reworking old stories into popular plays. (‘An upstart crow, beautified with our feathers,’ said his contemporary Robert Greene.) In a sense, Greene won the argument and, in the centuries that followed, books and their individual creators became fixed and finished icons.

Yet we didn’t stop messing around with stories. In the 1600s, a writer working under a pseudonym wrote a sequel to Don Quixote, irritating its author Miguel Cervantes so much that he produced a sequel of his own. In his romance Rebecca and Rowena (1850), William Thackeray parodied Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1820), which had itself reshaped the traditional tales of Robin Hood into the character we know today. Many people parodied Charles Dickens, and theatre directors continue to set Shakespeare’s plays in every time period imaginable. And those are just the most public reinventions of beloved fictional and true-life stories: before the Brontë children became famous writers themselves, they published a fanzine featuring made-up tales about the Duke of Wellington as well as various fictional kingdoms. We’ve managed to save a copy of that, but countless other clever household creations have been lost to history.

Were the Brontës growing up today, their zine would circulate far beyond the family parsonage. They’d post their stories online, adding them to millions of other fan-written stories, videos, and artworks. In modern fan fiction (or fanfic), familiar characters are set loose in different time periods, different stories, different relationships, different genders, and even different species. Fancy Harry Potter as a werewolf? Sherlock Holmes in the TARDIS? Then there’s a fanfic for you – in fact, likely thousands of them. And while fanfic writers do re-imagine TV shows, movies, comics, and even celebrities’ private lives, books remain among their most popular and enduring inspirations. Perhaps it’s because books leave the visuals to the imaginations of their readers: without canonical images, reinvention is even more tempting, and more satisfying.

Fanfic might sound like an adolescent distraction – and it surely is at times – but for its creators, it’s far more than entertainment. In October 2013, the Organization for Transformative Works (OTW), a US advocacy group with a large online archive of fanfiction, submitted a lengthy defence of non-commercial use of copyrighted works to the US Patent Office. Amid its legal arguments are some notably moving testimonies from fanfic writers, for example: ‘Fanfiction is the supportive, creative space for blacks who after seeing a movie in which all the main characters are white, think, “I would do it differently, and here’s how.” Fanfiction is for the girls who read a comic book in which the heroes are all men, and imagines herself as Captain America.’

Fan fiction gained notoriety after the publication of Fifty Shades of Grey (2011), E L James’s soft-porn bestseller loosely based on characters from Stephanie Meyer’s vampire series Twilight (2005-08), and fanfic might still be best known for its frequent and inventive smuttiness. But the creation and consumption of sexy stories can have its own higher purpose, especially for fans who don’t see their own sexualities represented in mass media. ‘Fanworks were and are vitally important to my acceptance of my queer sexuality,’ one fan testifies in the OTW letter to the US Patent Office. ‘If they were to be made unavailable, queer youth would lose a source of support in an often still shockingly hostile world.’

The relationship was an armchair tête-a-tête between one writer and one reader at a time. Now, that relationship is a noisy, chaotic, very public web

Fan fiction is also known for, shall we say, its wildly varied quality. But many a writer has learned to write by imitation, and all of us have gotten better only with practice. Fanfic writers are simply brave – or reckless – enough to publish their first drafts, and learn from other fans’ critiques. And fanfiction isn’t an exclusively amateur pursuit. Think of Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), or novels such as John Gardner’s Grendel (1971), Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), Geraldine Brooks’s March (2005), or Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres (1991). Each tells a classic story from the point of view of an underdeveloped character or characters, creating a new story that both stands alone and casts fresh light on its source. (A Thousand Acres, which sets King Lear on an Iowa farm, finally supplies the elder sisters with a motivation for their villainy.)

The scholars Sauerberg and Pettitt suggest that the digital age has closed a ‘Gutenberg Parenthesis’ – an idea that is itself a remix of the concepts in Marshall McLuhan’s book The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962). In the digital age, they say, the authoritative power of books is diluted, and our writing has acquired some of the ‘fluidity of orality’ that existed before the printing press.

The Gutenberg Parenthesis is a compelling idea, but I wonder if technology has simply exposed and encouraged a habit we’ve never lost. We’ve always reinvented stories over campfires, and by our children’s beds. In the age of print, we imagined what might happen if our favourite novels continued beyond their final pages. The difference today is that many of these reinventions and re-imaginings appear online, where they proliferate in plain view. The relationship between writers and their audiences has long been a series of armchair tête-a-têtes, between one writer and one reader at a time. Now, that relationship is a noisy, chaotic, very public web.

‘All worthy work is open to interpretations the author did not intend,’ said Joss Whedon, the creator of the US TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer and an imaginative force in the revival of Marvel comic characters such as the Avengers, in a 2012 conversation on the Reddit website. ‘Art isn’t your pet – it’s your kid. It grows up and talks back to you.’

So since Gutenberg, at least, our stories have had a dual nature. We’ve known them both as continuous waves of tellings and retellings, and as the far more manageable particles between the covers of books and magazines. The boundaries between those two states are troubled and getting more so, and they’re raising increasingly complex legal questions. But we need both kinds of stories, perhaps now more than ever.

The publishing business, despite its flaws, allows writers to make a living from their hard work and unique talents – as do the concepts of individual authorship and copyright. (And despite the brilliant work being done by a few amateur writers, literature without professional writers and editors would be impoverished indeed.) Meanwhile, the licence to reinvent – both privately and publicly – creates a modest but powerful path to a better world.

reading about girls who have epic adventures has helped my daughter expand her own possible futures

When I first wrote about my daughter’s Hobbit genderswap, many people said that fanfiction writers were way ahead of us, and so they were: Female Bilbo is a familiar fanfic character. My daughter isn’t the first reader who’s wondered what would happen if a girl stepped into Tolkien’s wonderful, timeless story, and I hope she’s far from the last.

My daughter can and does relate to characters – and real people – of different genders, different races, and different cultures. Stories will help her continue to do so. One of the wonderful things about fiction, after all, is that it allows us to use our imaginations to inhabit very different lives, and develop empathy for those who live them. But children at my daughter’s developmental stage identify most strongly with their own gender, and reading about girls who have epic adventures has helped my daughter expand her own possible futures. I know this: I can see it in the games she plays, and the stories she tells. As with the fanfic writers who find personal validation in their creations, Girl Bilbo has helped my daughter imagine the person she will become.

As a parent, literary genderswapping – and other kinds of narrative reinvention – have made it possible to share some of my very favourite stories with my daughter. Sure, I could try my hand at writing new books with female characters, as some of my critics have suggested, but my efforts could never replace those of Lloyd Alexander, or Mark Twain, or any of the other geniuses that wrote so well for children of other generations. Though they wrote in times when it was difficult to imagine central roles for girls, their stories still deserve telling, and genderswapping allows us to do so with all the joy and none of the old-fashioned stereotypes. Since my daughter and I read The Hobbit, we’ve swapped many characters in many classic children’s books. My daughter knows the originals are different – I’m a firm believer in full-disclosure remixing – and some day, I hope, she’ll read and treasure those books herself. But when she does, she’ll know an alternative version is possible, too.

For me, the most fascinating part of literary genderswapping is its illumination of my own assumptions. Not long ago, my daughter and I read an Ursula K Le Guin novel with a young male hero. When we switched the pronouns, I found myself pleasantly but repeatedly surprised by our heroine’s independence. She journeyed alone, building her own boats, casting her own spells, and passing tests of strength and wits as she confronted dragons and shadows.

Of course she can do that, I thought. Of course she should be able to. But I was raised on Boy Bilbo, and on a million other stories where boys – usually white, usually English-speaking, usually straight – assume the lead. If I wrote a girl-centric adventure story for my daughter, I might reflexively throw in a male companion, or put our heroine on an easier path. By switching pronouns, though, my daughter and I met a heroine who pushed the boundaries of both our imaginations and took us on a truly unexpected journey.