At the end of the 17th century, Madrid started to be populated, especially around Calle de Postas and Plaza Mayor, by kiosks, stores and street vendors selling chocolate. Individual licences were granted every year, but several street vendors profited from the curiosity towards the exotic drink by selling a dark beverage made less of cocoa and more from almonds, pine nuts, flour, acorns, coffee, bread and cookie crumbs, pieces of orange rind and even soil.

Detail from A Fair in Madrid (1779) by Goya. In the foreground is a beautifully rendered chocolate service. Photo courtesy the Prado Museum, Madrid

Trying to put a stop to the proliferation of competitors, in 1723 a group of professional chocolate makers made their request to form a guild, claiming it was time to protect public health from the threats of adulteration. The request was denied as superfluous, but the molenderos (from the Spanish for ‘to grind’) did not surrender. Twenty-five years later, in 1748, they tried again and found a more favourable response from the city authorities – finally interested in curbing the loss of revenue due to adulteration – but not from their colleagues. Many workers opposed to forming a guild because they were poor, and adulterating chocolate remained the simplest way for them to profit from its sale.

Stories similar to that of the Madrilenian chocolate-makers guild occurred in many other Spanish cities, as well as in the colonies. Indeed, tension between chocolate makers, informal vendors, consumers and authorities both followed and fuelled chocolate’s passage from being an exotic curiosity to a widespread commodity between the 17th and 18th century.

Greatly valued in Amerindian societies, chocolate had spread among Spanish settlers in New Spain by the 16th century. The great and immediate success of chocolate fascinates today’s scholars and novelists as much as it frightened contemporaries, who worried that ‘addiction’ and ‘greed’ – in the words of the Jesuit missionary José de Acosta in 1589 – would corrupt the bodies and souls of Spanish settlers. Indeed, as shown by the historian Rebecca Earle, the power of diet to create or dilute bodily differences destabilised borders between colonisers and colonised peoples, at the same time as it fuelled the fear of any Indigenous religious practices persisting.

The drink rapidly popularised to become an everyday reality for all strata of the Novohispanic population, consumed – as observed by a contemporary – ‘among Spaniards, as well as among indigenous and mestizos, mulattos, negros and other people, [drunk] during fasting days, Lent and vigils, in the morning as well as in the afternoon, at night and at many times of the day.’ In Ciudad de México, until the first half of the 17th century, chocolate could be acquired directly from natives on the street (until the latter were pushed out of its trade by Spanish and mestizo vendors) as cocoa paste in lozenge form, to which consumers could add what they pleased. Preparations ranged from the simplest one with water to more complex procedures with the addition of several spices and flowers, but the most popular way to consume it was hot with atole (a corn dough).

Unfortunately, the decline of the Indigenous population and the impoverishment of the soil that followed the conquest caused the collapse of cocoa’s production in the area, making it impossible to satisfy the growing demand. The insatiable Novohispanic market encouraged the cultivation of different qualities of cocoa in the regions of Guayaquil (in today’s Ecuador) and Caracas (in today’s Venezuela), where cocoa plants had been discovered by Juan López de Velasco as early as 1570. Guayaquil and Caracas quickly established themselves as the most important cocoa-growing areas, laying the foundations for an interregional market in the overseas colonies. The sweeter criollo cocoa from Caracas was more valued and appreciated than the very high-yield forastero cocoa produced in Guayaquil, therefore Caracas remained the main supplier of New Spain until the beginning of the 18th century. For its part, Guayaquil managed to overcome the existing prohibition to export its cocoa, and, thanks to its lower price (due also to the larger quantities of sugar employed for its preparation), became an increasingly successful competitor among the lower classes in the well-differentiated Novohispanic market.

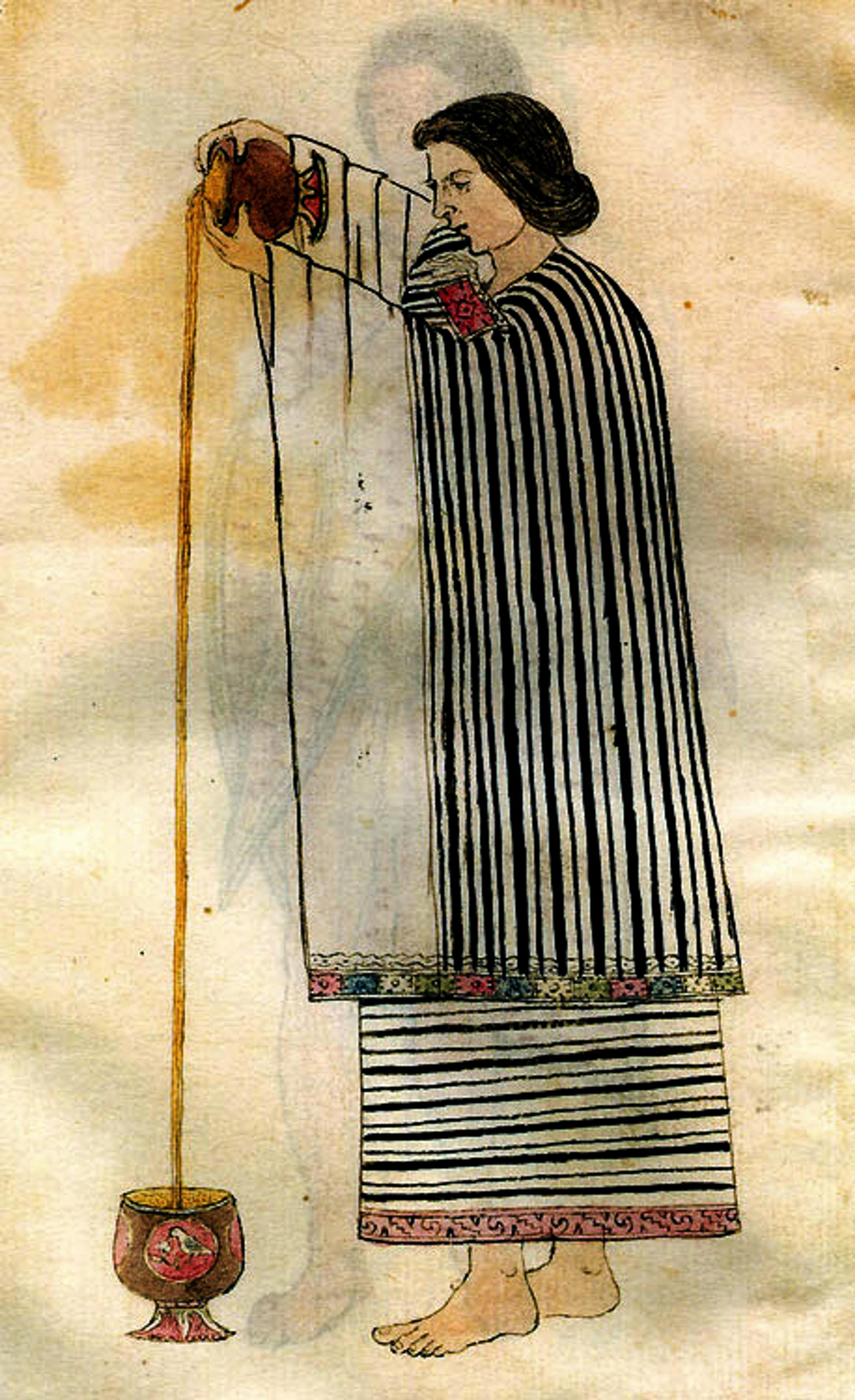

A woman pouring chocolate in an image from the Codex Tudela, a 16th-century Aztec pictorial manuscript. Courtesy Wikimedia

Indeed, trade regulations and the fear of what the French historian Serge Gruzinski called ‘colonial idolatry’ had to deal with the exploitation of commercial opportunities offered by the colonies’ natural resources within both colonial and European markets. This fuelled a series of controversies and disputes about the proper and correct ways to consume chocolate, which in turn fuelled further interest in the product. Although only 289 fanegas (or bushels) officially left the port of La Guaira near Caracas for Spain between 1620 and 1650 – and its commercial circulation remained limited in Europe – chocolate crossed the Atlantic, to travel already processed and transformed into a paste with basic ingredients added to avoid the rapid deterioration of the raw product. It passed through aristocratic and clerical networks, becoming a ‘reputation product’. The correspondence of the nobility offers countless testimonies of chocolate given as gifts, as in the case of the Duke of Albuquerque, who in around 1655 sent the Spanish royal family and nobles 22,000 lbs of chocolate – each pound packed in a little foil of gold.

A Lady Pouring Chocolate (c1744) by Jean-Étienne Liotard. Courtesy the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The drink, together with its rituals, rapidly became part of a series of codified practices and ceremonies, providing an opportunity for the renewal of consuming habits and sociability. Noble families competed with their recipes, and it was usual to have one’s chocolate prepared by a chocolate maker at home. Gradually, the role of Spanish nobility as a mediator of chocolate diffusion within aristocratic networks led to its ‘Hispanisation’ in the 18th century. Redeemed from its ‘barbarous origin’ through the addition of sugar and the simplification of its composition, chocolate was partially stripped of its exotic identity in order to acquire new symbolic associations in European, and especially Spanish, culture. The recipe for Spanish chocolate was a basic blend of cocoa, sugar and cinnamon (excluding most of the exotic spices heretofore used), but it was the technique used by the renowned Spanish chocolateros that made it famous throughout Europe.

Between 3 and 4.5 million lbs of the cocoa produced in Caracas ended up on the Dutch black market

Claims of Spanish excellence in the art of chocolate production went hand in hand with an increasing identification of the product with Spanish culture. Chocolate took on such importance in 18th-century Spain that even the entry on chocolat in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie opens with an acknowledgment of its diffusion in Spain, stating that ‘lacking chocolate in Spanish homes is like here [in France] being so poor not to have bread’. The political economy of consumption intertwined with the competition among empires, as a similar process of cultural appropriation took place with tea and coffee in France and England respectively from the late 17th century onwards. Imperial powers began promoting the consumption of certain products – especially psychoactive substances – based on material conditions and the possibility of controlling production and trade. In the case of chocolate, the control of imports and pricing policies, as well as reforms concerning modes of sociability and consumption, intertwined to both reshape taste and broaden demand.

Indeed, this diffusion could count on the attempt by the Spanish Crown to take back the Atlantic trade from the English and the Dutch. Indeed, smuggling and tax-avoiding practices were not a peculiarity of interregional trade, and until the beginning of the 18th century the revenue produced by the increasing success of chocolate in Europe had not replenished the Crown coffers. Between 3 million and 4.5 million lbs of the cocoa produced in the Spanish-owned province of Caracas ended up on the Dutch black market, loaded in Dutch armed ships – as attested by the secretary for the Spanish embassy in Holland, Nicolás Antonio de Oliver. In 1683, Amsterdam was the most important centre for the arrival and exportation of cocoa to various European countries, and – as claimed by a Barcelona merchant writing to someone in Cadiz – ‘cocoa is very expensive here … We can find it much cheaper in Amsterdam.’

Cocoa was ideal for trading and thus smuggling, as its harvest was continual and its plantations mainly stretched along the coast, facilitating contact with the Dutch ships. The prevalence of slavery-based plantations owned by the grandes cacaos (the Creole nobility of plantation owners) also favoured the illegal selling of cocoa by plantation and household enslaved people. Practically every social stratum was therefore involved in the illegal trade, as the Caracas economy was mainly based on the high demand in Ciudad de México for this valuable fruit. With the complicity of the authorities, merchandise was introduced and colonial products were made available on the market without taxes being paid, thus making a substantial amount of the production disappear.

After several failed attempts, in 1728 the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas was founded and placed in private hands, although the clauses for its foundation included a number of royal privileges and obligations. The company’s monopoly made it the only formal buyer of the region’s main fruit products and the only seller of raw materials and consumer products (with the consequent freedom to fix prices and transaction conditions), not to mention conferring it with both military and supervisory roles. Its entry on to the scene had significant consequences on interregional trade equilibriums between Caracas, New Spain and Guayaquil, with great consequences for the cocoa economy of all the regions, as well as for European markets.

As expected, once the Guipuzcoan Company was created, replacing Dutch traders and re-orienting exports towards Europe, the prohibition against Guayaquil cocoa in New Spain became more of a formality than anything else. The arrival of the company and the huge demand for chocolate in New Spain boosted both the cultivation and the imports of Guayaquil cocoa, which became the top import since 1728. But if the ‘Guipuzcoana’ changed the dynamic of interregional trade, what were the implications for the Spanish and European markets? The company had some success in regaining control of the Atlantic cocoa trade, but it also stimulated production and reoriented exports, laying the essential material foundations for a major availability of cocoa in Europe. Cocoa imports into Spain enjoyed a constant and substantial increase after 1728, while the transnational elite circulation of chocolate through ecclesiastical and noble networks gradually ceded to the geographical concentration of its consumption in Spain and a parallel diffusion outside aristocratic circles.

In the same years that the Guipuzcoan Company was being formed, small groups of workers specialising in producing chocolate arose in Spanish cities, the maestros molenderos de chocolate (or chocolate makers). In Madrid, they fought for decades to establish their guild until their successful petition in 1771, presented by a group headed by the enterprising chocolatero José Antonio Sanz. What had changed to grant the success of these molenderos? Indeed, the political climate of Spain was changing, and demand for chocolate was on rise. Chocolate spread beyond the capital, reaching the countryside through small and medium-sized cities, becoming a daily product for the upper classes and a semi-luxury good in which a growing number of people could occasionally indulge. It is not by chance that, by the mid-18th century, authorities for the first time explicitly started to express their concern over the accessibility of chocolate consumption ‘for the poor’. Furthermore, the motley assortment of poor ‘layabouts’ or people with other jobs had given way to a list of 128 people who identified themselves as maestros molenderos de chocolate, making a decent living off this work alone.

The flexibility of local production was a key factor in the democratisation of consumption

An entertaining and satirical Spanish copla (improvised folk song) from the end of the 18th century vividly introduces a wide range of stereotypical portraits of chocolate consumers, recounting how popular chocolate had become by then among different social classes:

Es el chocolate ahora

un almuerzo tan ligero,

que hasta las niñas en los barrios

gastan su chocolatero.

Hay algunas madamitas

con el tragecito inglés

que toman el chocolate,

y no lo pueden beber.

Medicos y Cirujanos,

hasta la gente de pluma

toman el chocolatito,

espesito y con espuma.

Tirulín, tirulín tirulero,

esto se lleva la fama,

chocolate con espuma

es lo que quieren las damas.

Los sastres y zapateros,

vendedores de hortaliza

cuando toman chocolate

en su casa no se guisa.

Tirulín, tirulín tirulero,

mirele usted que salaro,

que los lunes no trabajan

los señores zapateros.

Cuando los chocolateros

se ponen a trabajar

con la candela debaxo

hacen la piedra sudar.

Translation: ‘Chocolate is today, such a light breakfast, that even poor children, have their cup of chocolate. / There are ladies, dressed in the English style, who have chocolate, yet cannot drink it. / Doctors and surgeons, even intellectuals, have their chocolate, dense and foamy. / Tirulín, tirulín tirulero, this is the famous thing: chocolate with foam is what ladies want. / Tailors and cobblers, vegetable sellers, when they drink chocolate, they don’t cook. / Tirulín, tirulín tirulero, notice the wages, and on Mondays, cobblers don’t work. / When chocolate makers start to work, the fire underneath makes the grinding stone sweat.’

Here we can find everyone from middle-class ladies (no matter if traditional or fashionably dressed in the ‘English style’), professionals and intellectuals, as well as children playing in the neighbourhoods, to the emerging classes of artisans and maestros, who had to fast in order to allow themselves a cup of chocolate during the rest days. Chocolate was appropriated by different consumers through the creation of different social practices and rituals of consumption, ranging from the tertulia or upper-class gathering held at home to meetings in middle-class cafés, as well as in the kiosks that populated promenades full of people of any kind, or in private homes.

Indeed, the evolution of the chocolate makers’ struggle highlights the agency of different consumers, and the flexibility of local production was a key factor in the democratisation of consumption. The key move of the chocolateros was to renounce any pretence of monopoly in favour of an assurance role, based on the recognition that ‘chocolate is now daily food, especially for people of some class, and career’, and everything possible thus had to be done to avoid harming such consumers.

Quality and price differentiation became key words, and chocolate’s official list of prices was definitively changed to comply with the guild’s initial proposals in the last quarter of the 18th century to create three brands with the ingredients identified. These were well differentiated in terms of price and quality, also introducing the possibility of small ‘extras’ such as the fancy ‘labrada a la Italiana’ (meaning ‘made the Italian way’) or the use of exclusive cocoas from Maracaibo in Venezuela and Soconusco in Mexico.

Differentiating between qualities of chocolate allowed chocolate makers to respond and foster demand, expanding business to new social ladders while keeping its status high by ‘reinventing luxury’ through the first class of chocolate.

The differentiation of chocolate qualities was based upon increasing imports of Guayaquil cocoa, at the same time as fuelling this rise in imports. Reforms carried out after 1765 facilitated cocoa’s importation to Spain, thus eliminating the black market and stimulating its re-exportation to the rest of Europe. By then, cocoa was the second most important agricultural product (after tobacco) to come from the New World. Though Caracas was formally excluded from the Free Trade Decree until 1789, the change of equilibrium that came in 1778 nevertheless reduced the privileges of the Guipuzcoana, which definitively lost its footing because of the war with England, and closed in 1785.

If the creation of the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas had had the decisive if involuntary effect of boosting cocoa production in Guayaquil to feed the Novohispanic market, once the Guipuzcoana ceased to exist in 1785, Guayaquil’s high-yield forastero cocoa began to usurp exports of Caracas’s sweeter criollo cocoa across the Atlantic. Caracas managed to maintain its predominance until the end of the 18th century, despite Guayaquil’s exponential growth in cocoa production after 1789 – when the last restrictions on its trade were also removed. In 1770, Guayaquil had produced some 50,000 cargas of cocoa (where one carga was equivalent to 81 lbs); by 1801, that figure had doubled to 100,000 cargas. By 1821, with the production of 180,000-190,000 cargas, Guayaquil’s forastero overtook Caracas’s criollo.

The valuable criollo gradually lost terrain, and forastero cocoa – with its hybrids – took over the world

While the Guipuzcoana had played a key role in creating a market for cocoa by promoting the expansion of consumption, it was only free trade that could respond to this much stronger demand. Liberalisation didn’t fuel this rise but helped to fulfil the strong demand for cocoa created in the preceding decades by the growing differentiation in the chocolate supply.

Production and exports of Guayaquil cocoa burgeoned during the 18th century because of its rapid growth, high yield and low price, features that were not comparable with that of criollo cocoa from Caracas. Also, on the island of Trinidad off the Venezuelan coast, criollo plantations were decimated and replaced by forastero, giving origin to a series of profitable hybrids (named trinitario). The valuable criollo gradually lost terrain, and Guayaquil forastero cocoa – with its hybrids – took over the world.

Although Spain remained the largest single market for cocoa until the second half of the 19th century, consumption grew in the Philippines, and, from around the 1860s, the United States, Germany, Britain and France became the largest industrial transformers of cocoa beans. This geographical shift in consumption paralleled a growing differentiation in trade, with overseas merchants becoming increasingly independent from Western merchants. The spatial distribution of cocoa’s production witnessed the rise of plantations in the Brazilian state of Bahia, as well as in Trinidad and the Dominican Republic, and the seeds of forastero were among the protagonists of the Iberian empires’ attempts to fuel the colonisation of African possession in the mid-19th century.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Portuguese island colony of São Tomé and Príncipe together with the Gold Coast (in today’s Ghana) became one the world’s largest production areas. Indeed, forastero still makes up more than 80 per cent of world cocoa production today; it is mainly grown in Africa, with more than half of the 4 million tons of cocoa produced globally coming from sub-Saharan Africa (ie, Ivory Coast and Ghana), while criollo cocoa accounts for no more than 3 per cent of global production. The intricate plot of trade politics, competing social and cultural forms of appropriation and profitability plus chocolate’s resilience led to a series of boomerang effects that, by the 19th century, had made chocolate a global commodity, showing the interconnection and mutual influences between different areas (and competing empires) of the Atlantic world.