‘I have a terrible fear that I shall one day be pronounced holy …’

– from Ecce Homo (1888/1908) by Friedrich Nietzsche

On the morning of 24 September 1938, a Franciscan priest by the name of Herman Van Breda arrived at the Belgian Embassy in Berlin, Germany, carrying three large, overstuffed suitcases. He had an appointment with Viscount J Berryer, the secretary to the Belgian ambassador. They met at 11am, and Van Breda handed over the suitcases, with Berryer assuring him they would be sent high security to Belgium, and would not be investigated by the German authorities, in accordance with international rules on diplomatic documents.

These were no ordinary papers, however. The suitcases contained the archives of the great German philosopher Edmund Husserl.

Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, had died five months earlier. Once one of the preeminent cultural voices in German philosophy, his last years had seen him lose his professorship, his access to the University of Freiburg, and many of his friends, including his friendship to his closest student, Martin Heidegger. Despite having converted to the Lutheran Church 50 years earlier, Husserl was born Jewish, and the racial laws brought in by the National Socialists in 1933 had seen his life, like so many others, destroyed.

Outside Germany, Husserl’s fame and esteem remained high, and Father Van Breda had studied his work at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium. Van Breda travelled to Freiburg in order to study and catalogue Husserl’s unpublished writings, which the philosopher had often mentioned in his published books. These were no longer held at the university but had been removed by Husserl’s students and by his widow, Malvine, and taken to their house.

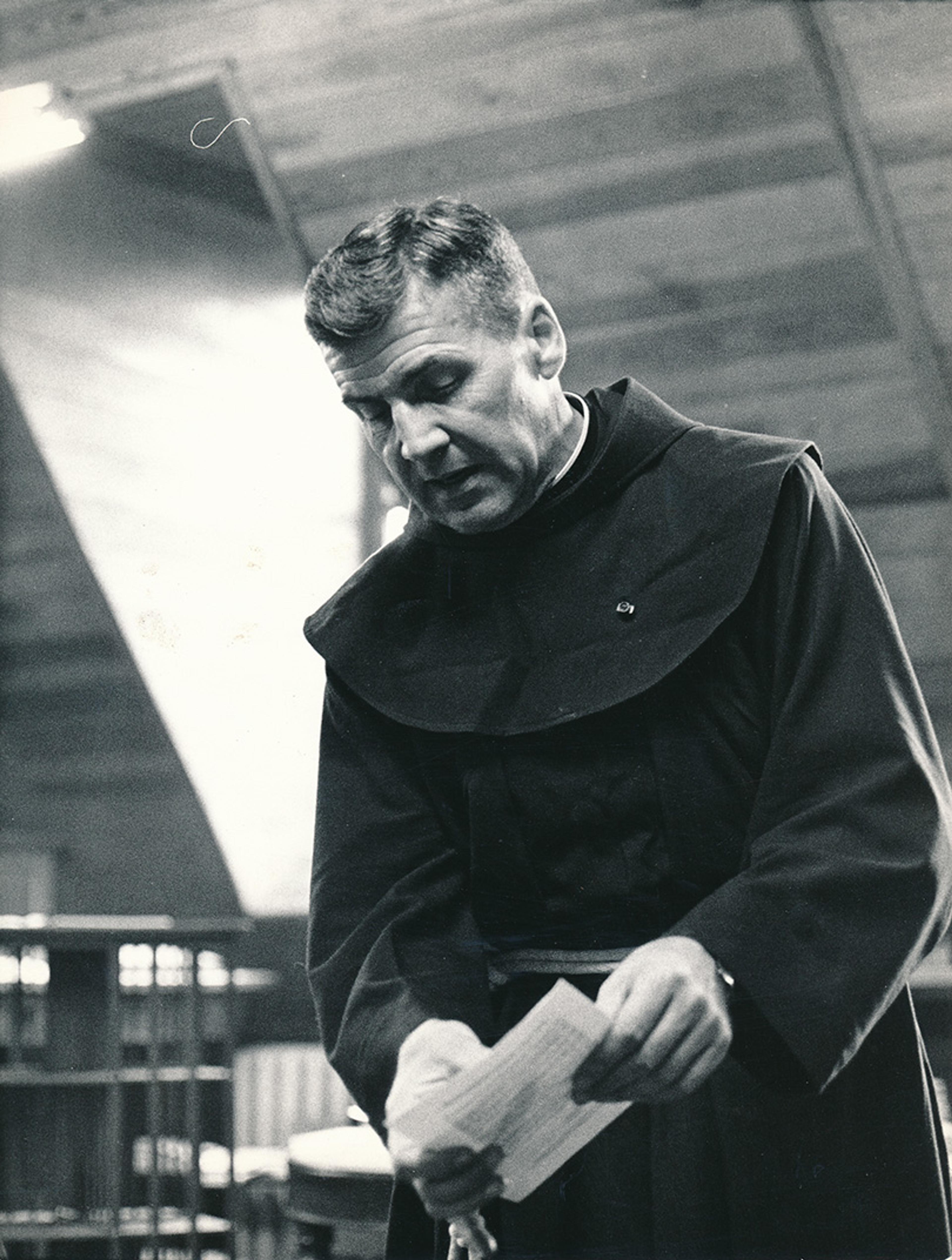

Herman van Breda. Courtesy Wikipedia

Van Breda was astonished to find some 40,000 pages of stenographic material that had been handwritten by Husserl, as well as around 10,000 pages of typed or handwritten transcriptions. All were in danger – the Nazi authorities had begun their programme of burning ‘degenerate’ (often simply meaning ‘Jewish’) art and literature and, should the archive fall into their hands, its destruction was inevitable.

Initially, Van Breda tried to get the papers out of the country by enlisting the help of nuns – he took the papers to a convent in Konstantz, which bordered Switzerland, with the idea that the sisters could carry them to safety a few at a time. But it soon became clear that this was too dangerous and, should the border be closed halfway through the operation, the papers would be split up, perhaps forever. So Van Breda took them back and deposited them in a monastery in Berlin-Pankow – a risky move as monasteries were now being searched.

Many French philosophers have started their careers by exploring the Husserl Archive. All because of the bravery of one Belgian priest

It was then he hit upon the idea of sending them via diplomatic channels, and soon after he met with Viscount Berryer. He left the handwritten originals with him – and the Belgian diplomat managed to get them to safety – while Van Breda placed the works that had been transcribed by Husserl’s assistants in his own luggage for the return to Louvain. Mercifully, his suitcase remained unopened by authorities.

Van Breda would spend the rest of his life establishing and helping to curate the Husserl Archive, overseeing the transcription of the entire body of work by Husserl’s assistants. It has become one of the most important philosophical archives in the world, and many French philosophers have started their careers by exploring it and using the works as jumping-off points – including Jacques Derrida, Paul Ricoeur and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. All because of the bravery of one Belgian priest.

To enter the Husserl Archive now is an act of homage: indexed, catalogued, cross-referenced, translated – the fragments have the feel of a cohesive whole. They are housed in a brightly lit, airy library, and it is difficult to reconcile the current fate of the papers with those stuffed suitcases. Now a research institute for phenomenology, with cheerful and helpful staff, able in moments to place before you a tiny slip of paper that one gust of wind or one Nazi following orders might have otherwise consigned to permanent oblivion.

This reveals one of the essential characteristics of an archive. To be an archive, the material must be public – there is no such thing as a private archive. It is located in space, a space outside the person whom it historicises. In this way, an archive is always threatened with destruction, and with it the person or time commemorated. Totalitarian governments of all stripes have recognised this – for all the defiance of the Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov’s phrase ‘manuscripts don’t burn’ – they do, and with them are immolated lives, ways of being, and cultures.

So, for the visitor to the Husserl Archive in Louvain (aka Leuven), whether they are there to study, or merely to browse, however light and airy the surrounds, to encounter the papers Husserl wrote on, figured out with, and touched, is to encounter a potential death, and to see how thin the line is between existence and nonexistence.

What is an archive? In particular, what is an archive when it is of a writer, philosopher or other thinker? Certainly, it would be expected to contain their published works – these are, after all, for public consumption, they are written with the idea of an audience in mind. But what of the rest? As is well known, what is published is often far from all of a particular thinker’s work – there are letters and diaries, first (and 101st!) drafts of poems, novels, philosophical papers. There are marginalia – notes written by great thinkers in the margins of other writers’ works (the poet Lord Byron’s notes in the margins of Isaac D’Israeli’s Literary Character of Men of Genius are far more famous than the book itself).

There are also writings less easy to categorise: notes to self, notes to others, notes to who knows who, shopping lists, and just notes that, while written in the writer’s hand, remain baffling to future researchers. Should these be part of the archive too? Where does one draw the boundary?

Some writers have been notoriously brutal in dealing with their unpublished scribblings – Marcel Proust was more than happy to see the 1.3 million words that make up his À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27) be published, but he insisted on his notebooks being burnt.

To sell or gift one’s archive is a way of not only holding on to posterity but shaping one’s (posthumous) image

The Czech author Franz Kafka went further, asking his friend Max Brod to burn everything he had written when he died. Brod chose not to – had he, Kafka would have been lost to history. In fact, a whole Kafka industry has grown up around him, so that we now know in microscopic detail about the life of one who wished to be forgotten – a situation satirised by Alan Bennett in his play Kafka’s Dick (1986), in which the writer comes back to find that even the size of his member is not only known, but the subject of scrutiny by cultural theorists.

Other writers are more comfortable with – or indeed encourage – their archive being saved, stored and assessed. Universities and museums build holdings of the works of great writers, as a resource for study. To sell or gift one’s archive – letters, drafts, notebooks, nowadays even laptops – to an institution is seen as a way of not only holding on to posterity but shaping one’s (posthumous) image. In many cases, the ‘unedited versions’ of the literary self are as finely edited as those written overtly for the public domain.

Thus, as Derrida has argued, creating an archive is not simply a literary (or philosophical) act but a political one. What is included and excluded from an archive is a way to pin the butterfly of a writer’s oeuvre, presenting them in a particular way, and possibly to a particular end.

One of the most famous cases of this is what happened to the archive of another German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche. Born in 1844, he remains one of the most controversial thinkers of all time, calling for nothing less than ‘a re-evaluation of all values’. All morality, Nietzsche argues, is socially constructed, and has no basis in ‘truth’. Worse, conventional Western morality, built around Christianity, is the morality of what he called ‘slaves’, rather than of healthy human beings. It was not for nothing that he declared: ‘I am no man, I am dynamite.’

Friedrich Nietzsche painted in 1894 by Curt Stoeving. Courtesy Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Always plagued by bad health, including piercing migraines and possibly syphilis, Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown in 1889, shortly after his 44th birthday. He would spend the last 11 years of his life being nursed, first in an asylum, then by his mother, and finally by his younger sister Elisabeth, who in 1897 took him in at her home Villa Silberblick in Weimar, and who also took control of his archive. It was to be a momentous decision.

Friedrich and Elisabeth had been close throughout their lives, but this changed in 1885 when she married Bernhard Förster. Förster was a leading figure in Germany’s far Right, and a prominent antisemite who described Jews as ‘a parasite on the German body’. He and Elisabeth set up an ‘ideal community’ in Paraguay, which they called Nueva Germania – New Germany – where they put into practice their ‘utopian’ ideas about the superiority of the Aryan race. In their beliefs, they were the sort of proto-Nazis to whom Hitler would appeal soon after.

She made her brother’s work not simply palatable to far-Right readers, but a work of advocacy for them

The failure of this community – most of these ‘superior beings’ were unable to cope with the harsh environment in which they found themselves, and died of starvation and disease – led to Förster’s suicide in 1889. Elisabeth continued to run the colony until 1893, returning to find her brother no longer sane.

By then, having sold barely any books in his lifetime, Nietzsche’s fame – unbeknown to him – had begun to grow. His published works were beginning to come back into print, and Elisabeth had access to a vast store of unpublished work. This she set about curating – transcribing it, editing it, and putting it into some sort of cohesive order.

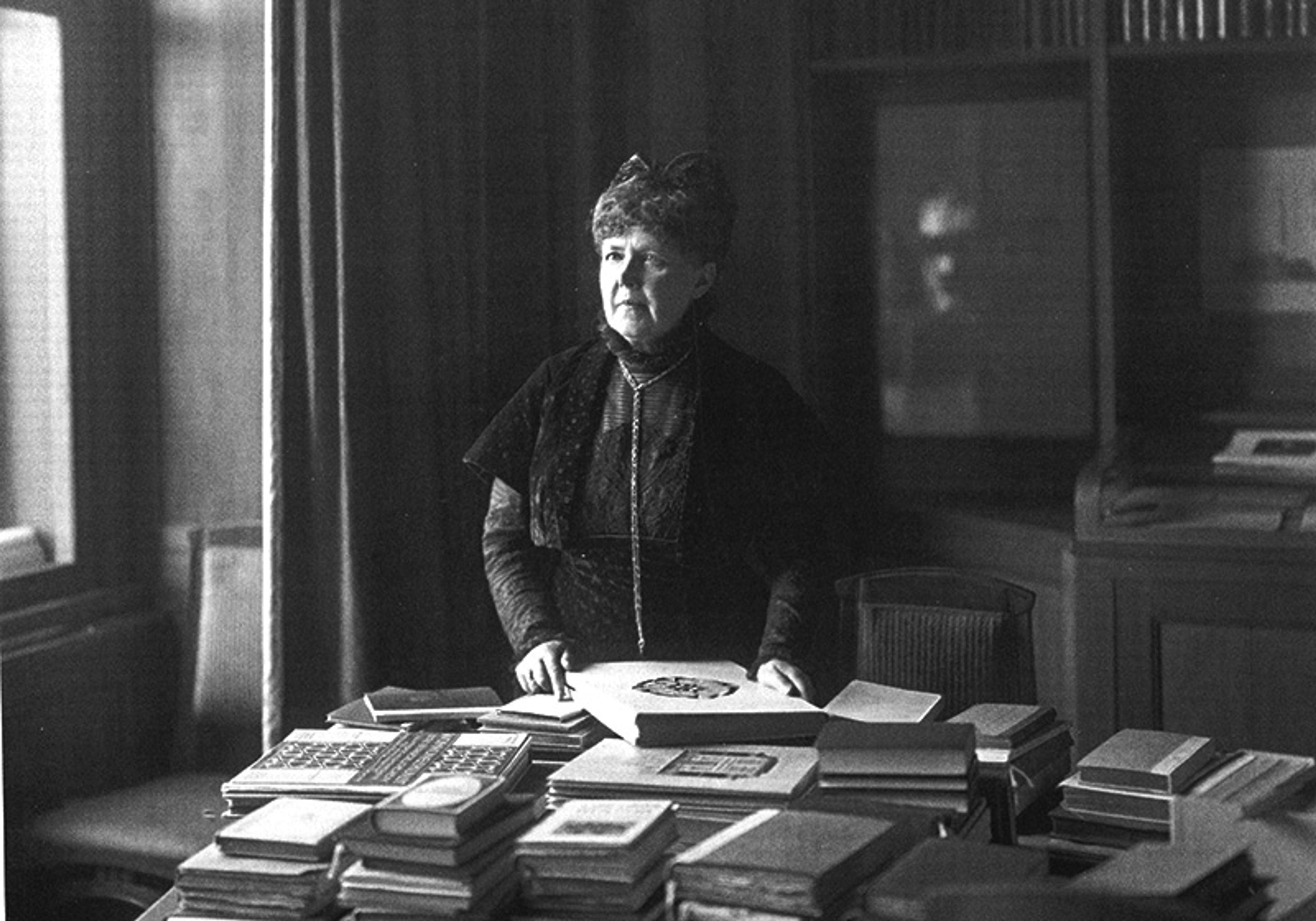

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche in 1910. Courtesy Wikimedia

Between 1894 and 1926, she published a 20-volume edition of her brother’s works, which included her most famous production, the book The Will to Power. Taking its title from a book Nietzsche had at one stage planned to write, it was advertised as his magnum opus – the final work he would have published if not for his ‘madness’.

It is a work of true audacity – if not Friedrich’s audacity, then certainly his sister’s. By selective editing, she was able to make her brother’s work not simply palatable to far-Right readers, but a work of advocacy for them. Nietzsche was not one to spare any particular religion from his attacks, but in Elisabeth’s hands his invectives against other religions were edited out, and those against the Jews pulled to the front. Nietzsche’s idea of the Overman – the future human who would have thrown off contemporary morality – hinted at the figure of the Führer and his minions, that is, Hitler and the pure Aryan race he hoped to engender.

Some have argued that Elisabeth was hoping to protect her brother by making his thinking more palatable to a predominantly white, Christian readership than it would otherwise have been. Or that her editing was for more personal reasons – she simply wanted to show how close they were. One cannot, of course, know what was going on in her head. But the effect was that Nietzsche became a sort of ‘house philosopher’ for the Nazis (a situation not helped by the shared jagged N and Z of their names). Elisabeth herself joined the Nazis in 1930, and Hitler helped fund the work of the Nietzsche Archive. He even attended Elisabeth’s funeral in 1935.

The stain of his alleged Nazism was to stay with Nietzsche for many years after the end of the Second World War. In his fascinating work How Nietzsche Came in From the Cold: A Tale of Redemption (2022; English translation 2024), the German cultural historian Philipp Felsch notes that, for many philosophers, particularly those of the Left, Nietzsche’s work was regarded as completely off limits – after all, hadn’t Hitler given Mussolini a Complete Works of Nietzsche as a 60th birthday present? One could only hope, as the philosopher Jürgen Habermas put it, that his ideas were no longer ‘contagious’ – they were a disease the world had been cured of with the defeat of the Nazis.

Nietzsche’s archive itself was safely tucked away in East Germany, where his works were banned. At the time, no one in the West knew for sure where the archive was – only later was it established that it had spent the years between the war and 1961 being carted around in wooden crates to be guarded at various Soviet military posts, before being dumped back outside Villa Silberblick, where Elisabeth had tended her brother for the last few years of his life.

They were following the dream of every archivist – to find the real writer behind what they had published

The task of transcribing and curating the archive fell – to everyone’s astonishment – to two Left-wing Italian scholars, the young philosophy student Mazzino Montinari, who did his work at Villa Silberblick, and his teacher and mentor Giorgio Colli, who collated the material recovered by Montinari.

The volume of material was overwhelming – the number of wooden crates was more than 100, containing, as Felsch notes:

an almost unfathomable abundance of material: fair copies and first printings of books published by Nietzsche himself; the lecture manuscripts and philological treatises from his time as a professor in Basel; the portfolios full of loose pages with ideas, concepts, and excerpts; as well as the notebooks he had used to record his streams of thought.

The unpublished fragments – a sort of intellectual diary, albeit a chaotic one – totalled upwards of 5,000 pages. To Montinari fell the task of transcribing Nietzsche’s dreadful, hurried handwriting, sometimes taking a whole day to finish one page. Aware of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s distortions, the curators wanted to get back to what Nietzsche had actually written.

But what were they looking for? In Montinari’s words, they were looking for ‘the true Nietzsche’ – which is more than just a truer version than the one his sister presented. They were following the dream of every archivist, and of many a casual reader – to find the real writer or thinker behind what they had published. It is a search for an urtext, an original from which the ideas develop. This is why Proust had his notebooks burnt – the version of events and thoughts he turned into literature was, once finalised, the ‘true’ version.

While distancing themselves from Elisabeth’s work, Montinari and Colli’s own was still a task of inclusion and exclusion – which fragments belonged to the archive, and which did not? Take for instance one fragment that reads, in quotation marks: ‘I have forgotten my umbrella.’ Is this part of Nietzsche’s archive? If not, why not? And if it is, then couldn’t anything be – from laundry lists to a journal of when it is time for the bin to go out.

Montinari and Colli felt that there were sound philosophical reasons for including and excluding fragments, or at least that their decisions could be defended. It was an idea that would be challenged from two unexpected quarters.

If Nietzsche was reviled in most of the West, then his stock was possibly lowest in France – the country had, after all, been occupied by the Nazis, and many of its intellectuals after the war took powerful Left-wing positions in a country where a third of the population had voted Communist in 1946.

But in 1964, at a conference on Nietzsche in Royaumont, a Cistercian abbey north of Paris, new French intellectuals, in the form of Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, came out against the idea of a ‘true Nietzsche’ – or a true anyone, for that matter. It was precisely the strangeness and the inconsistency of Nietzsche that made him the thinker he was. Any act of exclusion was an act of violence – what gave anyone the right to ‘decide’ on what Nietzsche ‘really meant’, and to exclude whatever was deemed superfluous to, or incompatible with, that meaning?

The attack was taken up by Derrida, who in a 1972 paper on Nietzsche mocked the sort of painful scholarly critiquing of exactly one fragment of the archive: the journal entry that says: ‘I have forgotten my umbrella.’ What possible criteria could there be for its inclusion? Or for its exclusion? Certainly, the meaning was clear, writes Derrida:

Everyone knows what ‘I have forgotten my umbrella’ means. I have … an umbrella. It is mine. But I forgot it.

But its place in Nietzsche’s writing could never be pinned down precisely – could it be a code? A dream? Did the quotation marks around it mean he was merely pretending he had forgotten his umbrella? Could it be the last line of a joke he was trying to remember? Or might it be a memory peg for the greatest insight in the history of philosophy? Anyone who presumed to know was uttering a falsehood – and that was true of every line Nietzsche left unpublished.

The reader would curate, include and exclude as they saw fit. They could escape the dominance of the editor

For thinkers like Derrida, alive to power relationships, the imposition of meaning always ran the risk of ‘totalitarianism’ – this version of the truth and no other. It does not matter how nonpartisan a researcher or editor might be, still they brought their own preconceptions, agendas and blind spots to their work.

The second attack on the methodology of the Italians came in 1975. The first volume of a new archive of the work of the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin was to be published, and the archive would contain – everything! While the job of transcription would still be done, that of curating would not, except to put the material in chronological order. The reader would then curate, include and exclude as they themselves saw fit. They could escape the dominance of the editor.

This was a precursor to an even more open form of archiving – the facsimile edition. Technology now allowed the photographing of manuscript pages, so they could be viewed as books or, later, on CD-ROM and then online. The final late Nietzsche volumes of Montinari’s edition were to be published long after his death, with the publisher announcing they would consist in ‘the transcription of Nietzsche’s complete notations, in the spatial arrangement of the manuscripts with all slips of the pen, deletions, and corrections – and no longer in the rectified form of linear texts.’

Nietzsche had started out as a philologist – a discipline that explored literary texts through close reading in order to find their ‘authentic’ or ‘true’ meaning. Later, he would dismiss the field as a ‘science for cranks’, ‘repetitive drudgery.’ But he also said this:

Philology should be understood here, in a very general sense, as the art of reading well – recognising facts without falsifying them through interpretation, without losing caution, patience, finesse in the drive for comprehension… whether concerning books, newspaper columns, destinies or weather events.

Weather events such as might require an umbrella? In a footnote, Felsch notes that the source has now been found – it is taken from an illustrated book of 1844 called Un Autre Monde (Another World), illustrated by Jean-Jacques Grandville, with text by Taxile Delord. It is a book of visual illusions, imaginary worlds, absurd taxonomies, and a satire on society and on books. What did it mean to Nietzsche? Against Derrida’s contention that nothing can be pinned to this fragment, scholars now delve into Un Autre Monde, dissecting it for Nietzschean resonances.

Nietzsche’s last published book was Ecce Homo, which translates as ‘Behold the Man’, with the subtitle ‘How One Becomes What One Is’. It acts as a sort of memoir, and the chapter titles – ‘Why I Am So Wise’, ‘Why I Am So Clever’, ‘Why I Write Such Good Books’ and ‘Why I Am Destiny’ – can be read as either sincere or as comedy – he was well aware no one was buying his books, let alone reading them. Lost in madness, he had no say in how he would be remade, but did offer a final plea in Ecce Homo that any public figure might offer: ‘Hear me! For I am such and such a person. Above all, do not mistake me for someone else.’