Several times each day, the ferries that connect Wellington, the capital of Aotearoa/New Zealand, to the country’s South Island cross the unpredictable 22 kilometres of the Cook Strait/Te Moana-o-Raukawa before gliding among the spectacular islands of the Queen Charlotte Sound/Tōtaranui into the small port town of Picton. Two or three times a week between December and April, the Southern Hemisphere’s summer and fall, the daily ferries are joined by massive cruise ships, some carrying as many as 5,000 passengers – enough to more than double the population of the normally tranquil town. These global tourists are drawn primarily by the world-famous Marlborough wine region, less than an hour away, and the ships are met by fleets of buses to carry the passengers to their intended destinations. Few visitors remain in the town itself, wandering its main street, exploring its shops and restaurants, or taking in the dazzling views. But, for those who do remain, the Edwin Fox maritime museum awaits. A lovingly managed local museum, it preserves the physical remains of the only surviving wooden vessel to transport indentured ‘coolie’ labourers from China, convicts to Australia, and settlers to New Zealand – a truly remarkable object of global history and world cultural heritage.

Built in 1853 in Thomas Reeves’s Union Docks on the Hooghly River across from Calcutta, the Edwin Fox was an entirely unremarkable vessel. At a registered tonnage of 836, it was well below the 1860 average of 1,200 tons, and with an overall length of 157 feet and the staid, square rigging of a man-of-war, the Edwin Fox was neither fast nor particularly large. It was exceptional for being unexceptional and, in some ways, old-fashioned even before the keel was laid down. Its design derived from the ‘apple-cheeked’ Blackwall frigates built on the Thames in London as replacements for the lordly and lugubrious East Indiaman. Round-bottomed and sturdy, more suited to carrying London general merchandise than for setting speed records, it had none of the prestige of the great tea and opium clippers like the Cutty Sark that captured the public imagination at the time.

More recently, the Edwin Fox forms part of the historical memory of Aotearoa/New Zealand. It was one of six vessels, including a Māori ‘voyaging canoe’ and Captain Cook’s Endeavour, honoured with a postage stamp in the run-up to the country’s 150th anniversary celebrations in 1990, and it appears as number 45 in the History of New Zealand in 100 Places website. But the Edwin Fox has a broader historical significance that has gone unremarked. Between its launch in 1853 and its demotion to serving as a coal storage hulk in 1905, this versatile and resilient sailing ship participated in many of the phenomena that comprised the greatest age of globalisation before our own time. Its decks are a privileged place for observing this foundational era of our modern world – and for writing its history.

The discipline of history was born in the 19th century and grew under the shadow of the emerging nation-state, and it mostly remains there today. Its subject matter may have broadened from members of the political, economic and social elites – overwhelmingly male – to include workers, women, racial, ethnic and sexual minorities, and Indigenous peoples, and its methodologies moved on from Leopold von Ranke’s pronouncements in 1824 that history was the study of the past ‘as it essentially happened’ (‘wie es eigentlich gewesen’) and that the strict ‘presentation of the facts, no matter how conditional and unattractive they might be, is undoubtedly the supreme law,’ but its focus remains stubbornly national.

This origin continues to mark the discipline, as most historians write about a single country, usually their own. Since the 1990s, however, the end of the Cold War, the digital revolution, the hegemony of neoliberalism, hyper-globalisation and the growing awareness of the climate crisis that affects humanity have all spurred the emergence of genres such as global, world and transnational history, which aim to look across national borders. But their ambitions bring challenges of their own. Abstract and macrohistorical processes often overwhelm individual stories of human agency and any sense of historical contingency. The vast scale of these projects often ignores the particularities of local conditions or avoids altogether the exceptions that may or may not prove the rule. Frequently, they privilege what Jeremy Adelman called ‘motion over place’ and ‘cosmopolitan commonness’ over local specificities. And, perhaps most ironically of all, history on a global scale has often struggled to capture what these changes meant for ordinary men and women around the world.

Some historians responded to these challenges by adopting the approaches developed by microhistory, a method, or as Thomas Cohen describes it, a ‘practice’ of historical enquiry, pioneered in the 1970s and ’80s by scholars of early modern Europe such as Carlo Ginzburg, Giovanni Levi and Natalie Zemon Davis. Microhistory focused on tightly bounded subjects, made intensive use of primary sources, and studied unusual individuals to explore larger questions. Emerging in the heyday of social history and fuelled by discontent with social science methodologies, the new approach would undertake what Ginzburg and his colleague Carlo Poni in 1981 described in the closest thing to a microhistory manifesto: ‘analysis, at extremely close range, of highly circumscribed phenomena – a village community, a group of families, even an individual person.’

One approach has been to focus on exceptional people, who for one reason or another travelled extensively

Microhistory’s subjects were men like Ginzburg’s Italian miller Menocchio and women like Zemon Davis’s French peasant Bertrande de Rols. To quote Cohen again, these were ‘obscure men and women, of those below high politics, inhabitants of smaller spheres, of villages and of towns’ darker quarters far from main squares and towering palaces’ – but in the hands of skilled mircohistorians they become active historical agents. Much more than their colleagues in other parts of the discipline, microhistorians paid particular attention to the historian as creator: cultivating a distinct narrative voice, developing a certain mode of storytelling, and inviting the reader along in the investigative process.

Perhaps the most important theoretical issue for microhistory, at least in its Italian variant, has been to understand the relationship between specific cases and larger questions. One answer was Edoardo Grendi’s concept of the exceptional normal, which Ginzburg summarises as ‘the notion that a case-study focusing on an anomaly may be the best strategy to build up a generalisation.’ Another was Giovanni Levi’s idea of ‘the reduction of scale, an analytical procedure [that] will reveal factors previously unobserved.’ The potential of microhistory to cure what ails global history should be clear. Ginzburg himself described it as ‘an indispensable tool’ of global history: ‘Microhistory and macrohistory, close analysis and global perspective, far from being mutually exclusive, reinforce each other.’

Global historians have embraced microhistorical methodologies to produce the hybrid genre of global microhistory. One important approach has been to focus on individuals, usually exceptional people, who for one reason or another travelled extensively. Linda Colley did this with Elizabeth Marsh, an 18th-century Englishwoman whose extensive travels spanned four continents. Maya Jasanoff used a similar approach to tell the story of Joseph Conrad and the age of steam. Others have looked closely at specific places to understand their often-unique connection to world history. This ‘think globally, act locally’ focus is well demonstrated by two very different examples: Dominic Sachsenmaier’s life of Zhu Zongyuan, a 17th-century Chinese Christian convert who never left his home province but nonetheless lived a remarkably globally entangled life, and Donald R Wright’s fascinating study of how global events affected Niumi, a very small and little-known region at the mouth of West Africa’s Gambia River, from the 15th to the 21st century.

We propose a different microhistorical approach: using the career of a single, unglamorous, workaday merchant vessel to tell the story of globalisation in the latter half of the 19th century. The Edwin Fox was a versatile and resilient sailing ship that, between 1853 and 1905, participated in many of the phenomena that comprised the greatest age of globalisation before our own time. It carried indentured labourers from China to Cuba, convicts from the United Kingdom to Australia, and settlers to New Zealand. It carried every conceivable commodity and constantly adapted to the changes wrought by steam-powered vessels and new infrastructure such as the Suez Canal. But the power of this story rests on the ways people, nations, economies and ideas were knit together in this foundational era of our modern world. Three layered examples will illustrate how the Edwin Fox is the vehicle for writing a global history that embraces the idiosyncratic, the unexpected, the everyday, the human.

Let’s begin with a moment toward the end of the Edwin Fox’s career. In May 1881, as the ship approached Bluff Harbour on the southernmost tip of New Zealand’s South Island, Jacob and Moir’s Southland Piano Warehouse proudly announced that it was bringing the community’s ‘first shipment’ of John Brinsmead and Sons’ prize-medal pianos, an ‘unrivalled instrument’ designed specifically for the ‘extreme climate’ of the colonies. Positioning ourselves on the decks of the Edwin Fox also allows us to think differently about a very common scene of petit bourgeois domesticity, the piano in the parlour, and in the process reveal some of the hidden complexities and consequences of 19th-century globalisation.

In the Victorian world, the piano was the symbol of treasured canons of middle-class values, representing the puritan work ethic, the morality of music, and the cult of domesticity. It was also a symbol of civilisation, and in colonial New Zealand pianos were one small part of settlers’ efforts to domesticate this wondrous and worrying new world into a proximate version of the familiar old. Advice books for potential settlers mentioned the instrument as one of the ‘few little articles of adornment or luxury’ that could give a ‘small wooded or cob house in New Zealand … the comfortable appearance of the pleasantest English houses’, and they turned up in the remotest corners of the colony. Pianos were also seen as a tool for Europeanising the Māori, although New Zealand’s Indigenous peoples came to employ them for their own cultural purposes.

The mass-produced piano of the 19th century was itself a consumer item with global implications, even (and perhaps especially) for people who never even saw one. Piano keys, along with a number of other products (such as combs, buttons and billiard balls), were made of ivory. Hard and durable yet delicate, luminous and unmatched as a medium for carving, historians have dubbed ivory ‘the plastic of its age’. And by the late 19th century, the global appetite for the precious substance was insatiable. The UK alone imported 500 tons of ivory each year between 1850 and 1910, and it was not the largest producer of pianos at the time; the United States took that title. W E B Dubois captured the global nature of this capitalist enterprise in 1946:

It all became a characteristic drama of capitalistic exploitation, where the right hand knew nothing of what the left hand did, yet rhymed its grip with uncanny timeliness; where the investor neither knew, nor inquired, nor greatly cared about the sources of his profits; where the enslaved or dead or half-paid worker never saw nor dreamed of the value of his work (now owned by others); where neither the society darling nor the great artist saw blood on the piano keys; where the clubman, boasting of great game hunting, heard above the click of his smooth, lovely, resilient billiard balls no echo of the wild shrieks of pain from kindly, half-human beasts as fifty to seventy-five thousand each year were slaughtered in cold, cruel, lingering horror of living death; sending their teeth to adorn civilization on the bowed heads and chained feet of thirty thousand black slaves, leaving behind more than a hundred thousand corpses in broken, flaming homes.

This exploding business also had severe implications for Africans. Ivory was ‘steeped and dyed’ in human blood, as the explorer Henry Morton Stanley put it, referring to the armies of people – many of them enslaved people – who were essential to this massive trade. To meet the growing global demand, ivory hunters had to pursue elephants deeper and deeper into the African hinterland and, by the 1870s, the East African caravan trade had expanded well into the Congo Basin. Indeed, the ivory that went into the pianos that the Edwin Fox took to Aotearoa/New Zealand was probably carried to the African coast from hundreds of kilometres inland on the shoulders of bound porters before being shipped by dhow to Zanzibar (in present-day Tanzania), the export hub for Europe and the US. And, until 1873, the porters who carried the tusks were sold in Zanzibar’s slave market along with their alabaster cargo – unless they died first.

The Edwin Fox connected the Victorian parlour to the African savannah

The flourishing ivory trade also led to the wholesale slaughter of African elephants and virtually eliminated the entire population south of the Zambezi River and much of it along Africa’s eastern coast. The result was a profound change in the region’s ecology. Elephants are one of the great terraforming species on Earth. They can consume as much as 272 kg of vegetation each day, knocking down trees and devouring bushes to create grasslands, the great savannahs of eastern Africa. The deaths of millions of elephants for their tusks resulted in a substantial increase in the area of eastern and central Africa covered by brush and woodland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As ecologically significant as the elimination of elephants was along this ivory frontier, it also created new opportunities for local people. Where before the Nyamwezi, Shambaa, Kamba, Ilchamus and others had been hunters, they now turned toward producing grain and raising cattle to feed the seemingly endless caravans transporting ivory and enslaved people from the interior to the coast.

The ivory trade in Zanzibar c1890-1910. Courtesy the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Perhaps the greatest disruption wreaked by the ivory industry came from an unlikely source: the tsetse fly. A large parasitic insect indigenous to the tropical regions of Africa, the tsetse is the primary biological vector for Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, the protozoa that cause the disease known as sleeping sickness. A debilitating neurological condition, sleeping sickness – so-called because of the circadian-rhythm disruptions it causes – results in swelling of the brain that will eventually cause death if left untreated. The tsetse’s preferred environments are thick brush and woodland areas. Historically, African societies kept the disease somewhat at bay by carefully managing these environments. But with the expansion of the 19th-century ivory industry and its attendant slaughter of elephants, the miombo woodlands and acacia scrub of central and eastern Africa expanded dramatically, and the tsetse’s breeding grounds bloomed along with them.

The ivory trade undoubtedly contributed to a staggering number of deaths; estimates range from hundreds of thousands to millions. But, in carrying a shipment of John Brinsmead and Sons’ prize-medal pianos in her hold, the Edwin Fox connected the Victorian parlour to the African savannah – and, in doing so, linked the colonialisation of Aotearoa/New Zealand to that of eastern Africa and beyond. It truly was a seagoing emporium fully stocked with histories of violence, exploitation and unintended consequences for a globalising age.

This ‘junior England’, as Mark Twain dubbed New Zealand, was transformed by settlers who arrived on the Edwin Fox and ships like it. Indeed, 19th-century globalisation resulted in the voluntary mass-migration of millions of people, and the Edwin Fox also carried those who chose to travel across the globe. These migrants often played critical roles in the establishment and development of the many settler colonies developing at the time. For instance, between 1873 and 1880, the Edwin Fox made four voyages from Great Britain to New Zealand carrying settlers under the audacious and controversial assisted immigration and economic development project designed by the flamboyant and visionary colonial politician Julius Vogel. Some prospered, some found the new country no more welcoming than the old, while others – probably most – made good if not spectacular lives. But, in all cases, their lives were part of the story of globalisation.

One of them, Margaret Williams Hocking, who was on the 1878 voyage with her husband John, left an important trace in the historical record. The Hockings’ first position was on a farm in Richmond, 13 kilometres from Nelson, but they soon left because of the primitive living conditions: a hut with no conveniences and a camp oven over an open fire on which to cook. From there, they went to Reefton, in the Inangahua goldfields, 200 kilometres to the southwest. Founded in 1871, the town was born upon the discovery of gold-bearing quartz reefs the previous year. They would have travelled by coach along the windy, hilly road that crossed numerous rivers. With luck, the journey would have taken three days, and they would have spent the nights in one of the numerous accommodation houses along the route and in the towns of Murchison and Lyell. Although she was heavily pregnant, Margaret chose to ride outside the coach, next to the driver, whom she had occasion to chastise for swearing at his horses during a difficult river crossing. The Hockings found plenty of fellow Cornish in Reefton. Like tin in Cornwall, Reefton quartz was deep-shaft and hard-rock mining, and the companies paid good wages to experienced miners.

The story of migrants such as Margaret Hocking is one of creation, innovation and development

The Hockings were both fervent, evangelical, teetotal Methodists, and they were active in Church groups. Margaret helped found the local branch of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and, in August 1885, John opened a temperance hotel offering ‘hot tea, coffee and pies … at all times’ to the ‘Temperance public’. In 1886, the Hockings moved to Black’s Point, which was closer to the mines. They took over the Williams Hotel there but abandoned the liquor licence and turned the bar into a shop, naming the new business Mrs Hockings’ Boarding House and Store.

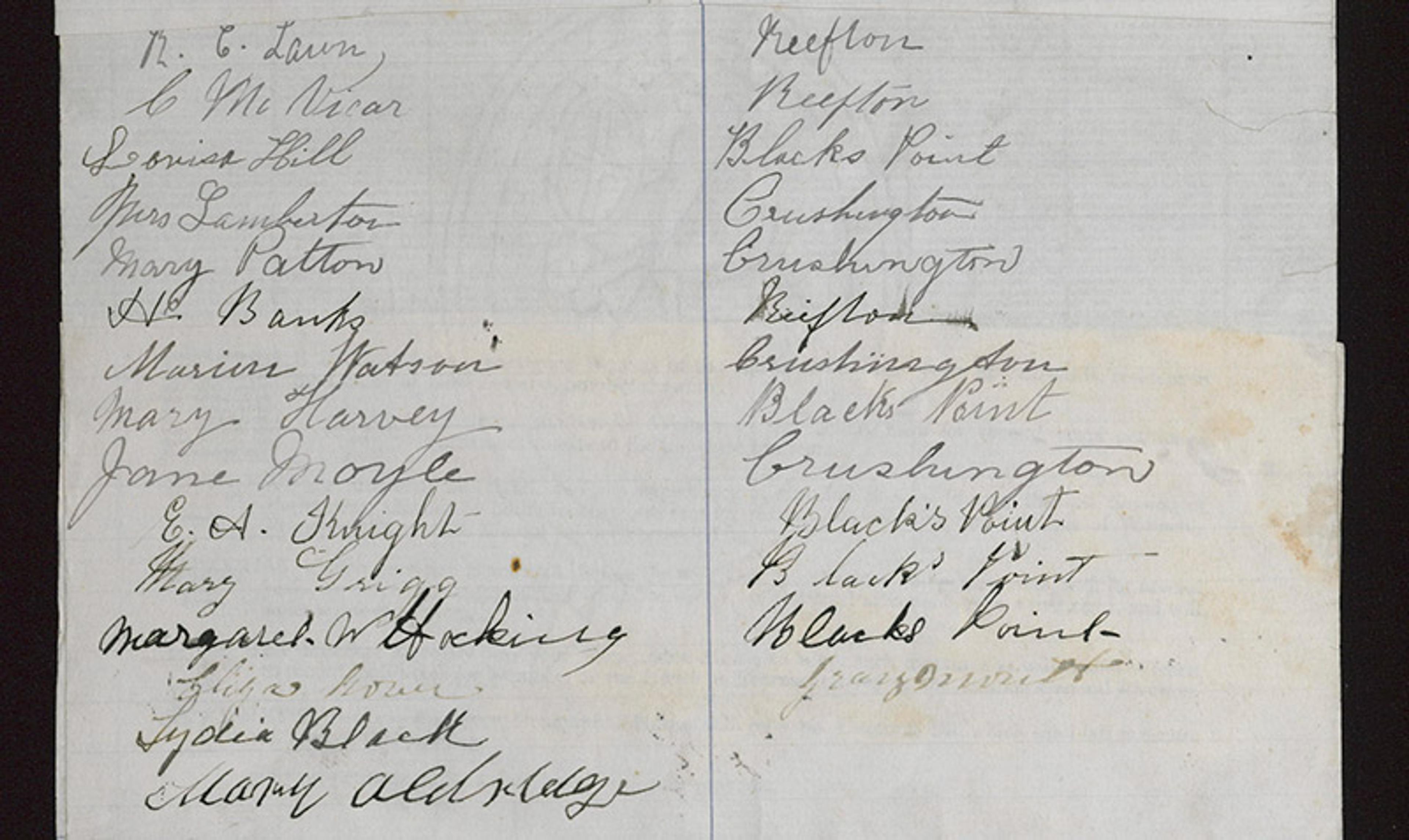

Driven by her conviction that women’s suffrage would pave the way for prohibition, Margaret, described by her granddaughter as ‘a fearless speaker [who] never shrank from saying what she felt to be right’, became a leader in the local suffragette movement, going door-to-door to convert women to the cause. Women in New Zealand won the vote in 1893 and were the first in the world able to vote in national elections. This achievement was in large part the product of the women who, led by the suffragette Kate Sheppard, presented mass petitions to parliament in 1891, 1892 and 1893. Along with those who signed the 1835 Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, the nearly 32,000 signatories to the 1893 ‘monster’ suffrage petition are now remembered as ‘the signatures that shaped New Zealand’. Margaret Hocking’s signature, on page 251, was one of them.

Margaret Hocking’s signature on the suffrage petition of 1893. Courtesy NZ History

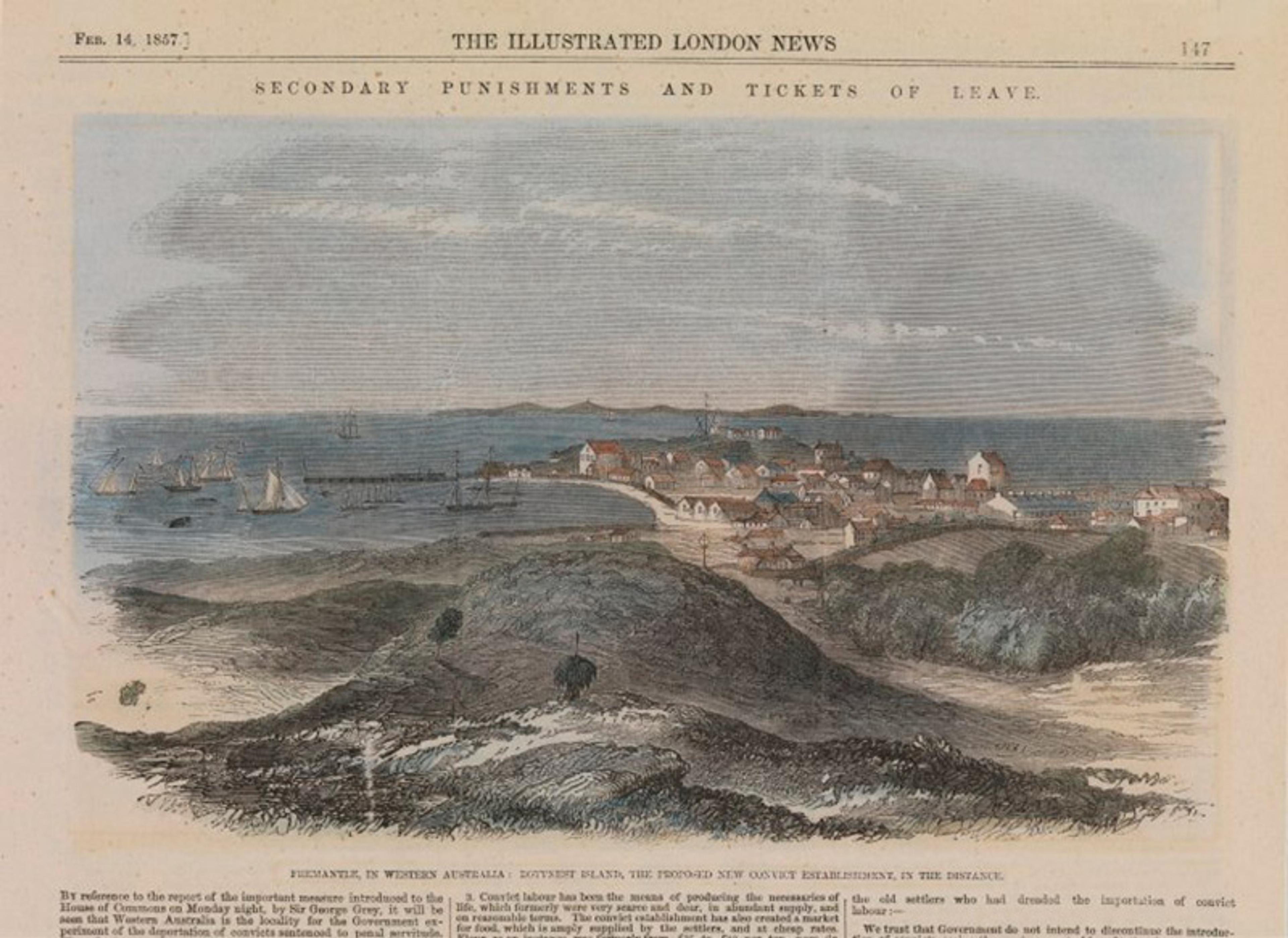

The story of migrants such as Margaret Hocking is one of creation, innovation and development. But the establishment and growth of these settler societies was made possible only through the expropriation of Indigenous lands. This was an aspect of globalisation the Edwin Fox was involved in, too. Our final story takes place at the end of the ship’s 1858 voyage to Western Australia with a cargo of 280 convicts. And it reveals the deep linkages between penal colonialism and settler colonialism in the age of globalisation.

Christmas Eve 1858 dawned hot and breezy. As Captain Ferguson, the master of the Edwin Fox, prepared to depart with the turning of the tide, the schooner Preston arrived in port and dropped anchor at the mouth of the Swan River. The two ships were there for different reasons, but they shared a common thread in the grand scheme of Australia’s colonisation. Much smaller than the Edwin Fox, the Preston was built by William Owston at his shipyards on Preston Point, a few kilometres up the Swan River. It was a fast ship, capable of completing the 350-nautical-mile run from the Albany settlement to Fremantle in just three days.

On the morning of 24 December, the Preston had just arrived on one of its regular mail runs up the coast. This time, however, it also brought four Aboriginal prisoners to serve two- to three-year sentences at the Aboriginal jail on nearby Rottnest Island. Sitting in the harbour anchored side by side, the two ships had both just completed their own middle passages of sorts, and both were playing a vital role in the colony of Western Australia’s economic development. The convicts aboard the Edwin Fox were brought from the UK to expand the colony’s labour force and further integrate Western Australia into the global economy. The Preston’s Aboriginal prisoners were brought to Fremantle to serve prison sentences, but they embodied a process of land expropriation and labour exploitation that was central to the colony’s establishment and continuing development. Neither of these two phenomena would be possible without the other, and neither would be complete without the other.

Western Australia’s colonisation occurred during a moment of heightened attention to the British Empire’s Aboriginal policy. Following the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, and especially after the passage of the British Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, many humanitarians turned their attention to the plight of Indigenous peoples in the empire’s many colonies. The result was a report to Parliament’s Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes in 1837. The report documented colonialism’s devastating effects on Indigenous peoples; it included hundreds of pages of testimony from Indigenous peoples and their humanitarian supporters, as well as colonial governmental and military officials. It also set forth a series of recommendations that colonial settlements develop policies to safeguard Indigenous lives and land through the rubric of ‘protective governance’. Many historians have suggested that this report ushered in a so-called new era of peaceful coexistence throughout the empire but, despite the abovementioned recommendations, the colony of Western Australia adopted brutal policies toward local Indigenous peoples throughout the 1830s and ’40s.

Initially, the colony had attempted to protect the local Nyoongar people. The governor James Stirling’s first act was to criminalise ‘fraudulent, cruel, or felonious’ behaviour toward Indigenous peoples in the colony. Despite this extension of legal protection, colonial administrators and settlers failed to recognise the centrality of the land to the Nyoongar people’s spirituality and cultural ways of knowing. As a result, tensions – especially over scarce resources and property rights – continued, and violence toward Indigenous peoples escalated. For instance, in 1832, an Indigenous leader named Yagan and his father Midgegooroo were arrested and charged with ‘murdering’ a settler. Yagan had killed a settler named Erin Entwhistle, but only after another settler, Thomas Smedley, had shot and killed a member of his tribe while they gathered potatoes. Under Nyoongar law, then, the killing was considered justified. Yagan and his father escaped captivity, but they remained wanted criminals. In 1833, the colony offered considerable rewards for their capture and/or death; within a few months, both Yagan and his father were dead at the hands of settlers.

A Whadjuk Nyoongar man received six months hard labour for possession of an empty gin bottle

Over the next two decades, settler scorn and contempt for the Nyoongar people grew as peaceful relations deteriorated. In 1834, the colony established a police force to protect settlers from the ‘depredations of the natives’, despite the fact that most victims of violence in the colony were Indigenous. Colonial officials also charged the police with developing a ‘register’ of all Indigenous groups in the region and providing a monthly report to the governor on their movements. By the late 1850s, most of the Nyoongar had been forced to live on the peripheries of the colony, where they worked under slave-like conditions on outposts and settler ranches.

In many ways, this world that the Edwin Fox had sailed into in 1858 was a tale of two prisons: Fremantle for convicts from Britain and its purlieus, and Rottnest for Aboriginal prisoners from the frontier of colonial Western Australia. In both cases, forced removal and transportation were integral parts of the punishment regime. But, if similar in form, they served specific yet distinct ends. For the British convicts, the punishment for their crimes – large or small – was forfeiture of the right to live among friends and family and banishment, often for life, to an impossibly remote and unknown place on the other side of the world. The goal was reformation and rehabilitation; the corollary benefit to the empire was their labour, which in no small way furthered the colonial project. For the Aboriginal convicts, the punishment for their crimes – real or fabricated – was banishment to a place known to the Nyoongar people as ‘Wadjemup’, meaning ‘place across the water where the spirits are’, where they subsisted on a diet of boiled cabbage and whatever they could catch for themselves on Sundays, their day of ‘rest’. They laboured from sunup to sundown, which was supposed to instil a sense of Victorian industriousness. The goal was so-called civilisation, but their removal from their homelands also served the colonial project. In both cases, the voyage and imprisonment – the exploitation of their labour, lives and land – served the overarching needs of the capitalist imperial system in which they were imbricated.

Freemantle and, in the distance, the proposed new convict establishment at Rottnest Island. Courtesy the State Library of Western Australia

Aboriginal prisoners, Rottnest Island, undated. Courtesy the National Library of Australia

Viewed together, the convict transportation system and the Aboriginal imprisonment complex of Western Australia contain illuminating parallels. The crimes that these men committed often verged on the absurd. Consider the cases of Hans Janssen and Durden: Janssen, a Kentish man, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and transportation for stealing three empty sacks; Durden, a Whadjuk Nyoongar man, received six months hard labour at Rottnest for possession of an empty gin bottle. Offences were also often eerily similar: William Graham, a poacher from Longdale, was sent to Fremantle not for the crime of poaching but for assaulting a gamekeeper named Thomas Simpson; Pardu Paddy, a Minang Nyoongar man who was arrested for receiving parts of a stolen sheep, was sentenced to three years hard labour at Rottnest for striking an Indigenous constable named Bobby. And both systems occasionally levied harsh punishments on the very young. Such was the case with Chillipete, a 14-year-old Juat Nyoongar boy sentenced to three years for starting a brushfire – a traditional Nyoongar practice – and William Hodgkinson of Nottingham, a 16-year-old shoemaker apprentice sentenced to six years transportation for breaking and entering a neighbour’s house.

Finally, both systems exacted a psychological toll on their victims. Such was the case for Thomas Bushell, a semi-literate Irish soldier. Bushell served in the Crimean War, after which, while stationed in Malta, he was arrested for striking a superior officer, court-martialled, and sentenced to life imprisonment and transportation to Western Australia aboard the Edwin Fox. (Bushell was one of nine convicts on the Edwin Fox’s 1858 voyage sentenced by courts-martial in various British imperial outposts, including Mauritius, Barbados and Canada.) When he arrived at Fremantle, Bushell was initially set to work in the prison’s kitchen. Within two months, however, he was punished with solitary confinement for ‘wilfully destroying prison property’. From there, matters went from bad to worse. Bushell attacked a guard, and when subsequent punishments became intolerable, he attempted suicide. This latest ‘infraction’ landed him in the local insane asylum. From there, Bushell was transferred in 1865 to a British convict prison also on Rottnest Island, where he stabbed a warden in the shoulder with a 13-inch dough knife. Although clearly mentally ill, he was sentenced to death and hanged three days later, ending his tormented existence.

A few years earlier, also on Rottnest Island, a civil engineer named Henry Trigg hired to build a lighthouse using Aboriginal labour, noted the following of his imprisoned workers:

The prisoners will sit down and weep most bitterly, particularly old men, or those who have left wives and children on the mainland. When they see the smoke from the fires at the place where they have been accustomed to meet when unshackled and free, memory wanders over the scene of bygone days, they seem intensely alive to their lost freedom, and lamenting bewail their captivity.

One of the stated intentions behind the prison on Rottnest had been that Aboriginal prisoners would be ‘gradually trained in the habits of civilised life’. Of course, the imprisonment of Indigenous peoples has long gone hand in hand with the process of colonisation.

The costs and consequences of 19th-century globalisation were borne disproportionally by the most marginalised. In the colony of Western Australia in particular, convictism was transformative, saving a beleaguered outpost by pulling it into the global economy. In the process, it spurred the settlement’s expansion further into the homelands of the Nyoongar people, setting the stage for more than a century and a half of colonial exploitation and domination, widespread land dispossession, and continuing mass incarceration.

Between 1850 and 1914, the world changed in unprecedented ways. More people than ever before travelled long distances across seas and oceans out of necessity or in search of a better livelihood, and more goods were traded to more places. Europeans, joined by the Japanese and the Americans, subjected more parts of the world and more people to colonial rule than ever before, dispossessing Indigenous peoples en masse. New technologies like steamships and the telegraph made it possible to move people, goods, ideas and information more reliably and often more quickly than ever before. But the remaking of the world’s economy also resulted in environmental change on a massive scale. And if a globally interconnected planet created tremendous wealth on a scale never seen before, it was not evenly shared. From the rapid expansion and intensification of trade around the globe to the spread of industrialisation and the integration of settler colonies into imperial markets, this was globalisation in the late 19th century.

The life of the Edwin Fox coincided perfectly with these developments, and this workaday sailing ship helped connect the world in the first great age of globalisation. Its story can help us understand what the process meant for the people who travelled on it, and even for those who never laid eyes on it then, and encourage us to consider fully the consequences of our own moment of globalisation now.

This Essay is based on the book The Edwin Fox: How an Ordinary Sailing Ship Connected the World in the Age of Globalization, 1850-1914 by Boyd Cothran and Adrian Shubert, published in 2023 by the University of North Carolina Press.