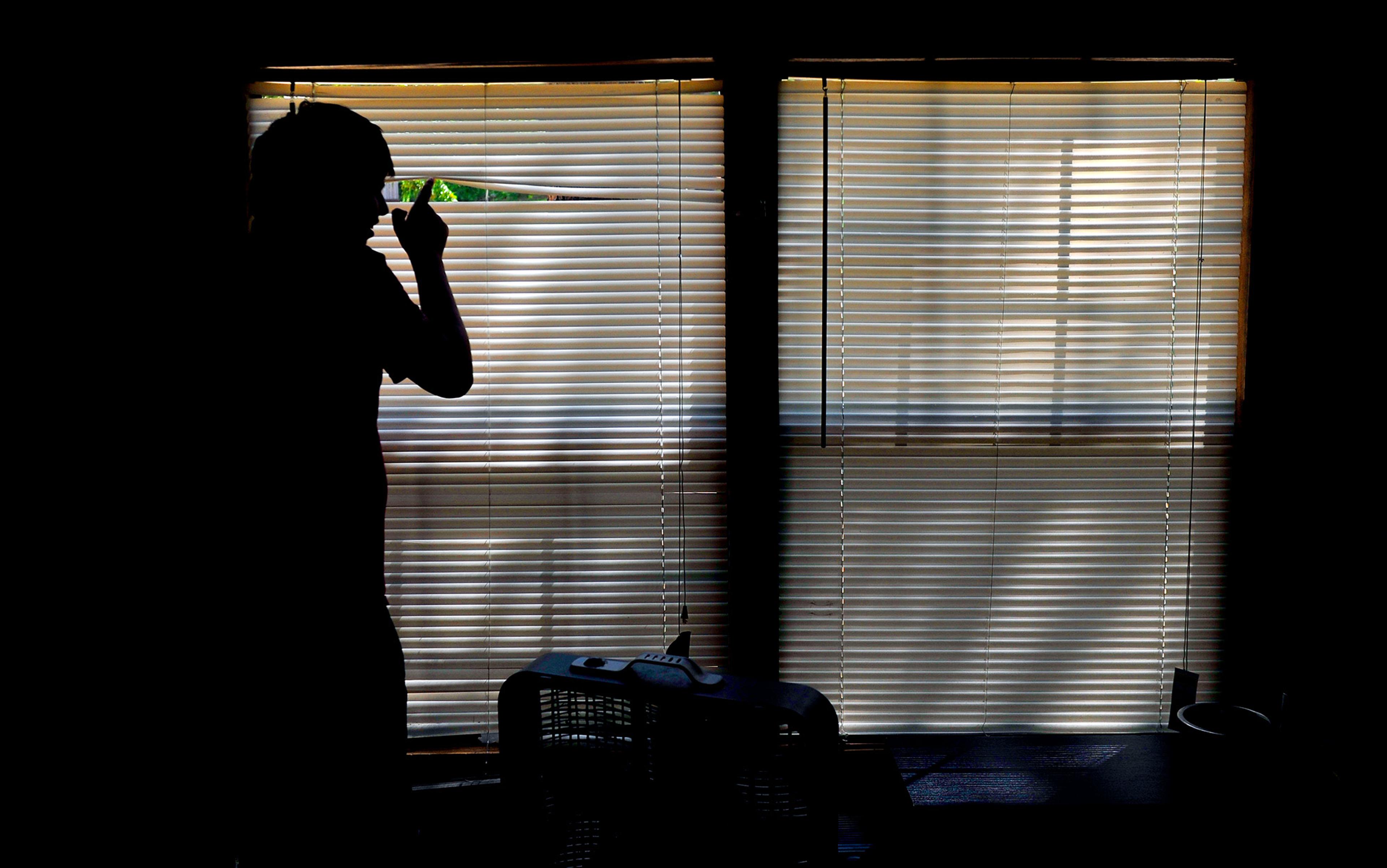

Sharon calls herself a universal reactor. In the 1990s, she became allergic to the world, to the mould colonising her home, the paint coating her kitchen walls, but also deodorants, soaps and anything with plastic. Public spaces rife with artificial fragrances were unbearable. Scented disinfectants and air fresheners in hospitals made visiting doctors tortuous. The pervasiveness of perfumes and colognes barred her from in-person social gatherings. Even stepping into her own backyard was complicated by the whiff of pesticides and her neighbour’s laundry detergent sailing in the air. When modern medicine failed to identify the cause of Sharon’s illness, exiting society felt like her only solution. She started asking her husband to strip, shower and off-gas every time he came home. Grandchildren greeted her through a window. When we met for the first time, Sharon had been homebound for more than six years.

When I started medical school, the formaldehyde-based solutions used to embalm the cadavers in the human anatomy labs would cause my nose to sear and my eyes to well up – representing the mild, mundane end of a chemical sensitivity spectrum. The other extreme of the spectrum is an environmental intolerance of unknown cause (referred to as idiopathic by doctors) or, as it is commonly known, multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS). An official definition of MCS does not exist because the condition is not recognised as a distinct medical entity by the World Health Organization or the American Medical Association, although it has been recognised as a disability in countries like Germany and Canada.

Disagreement over the validity of the disease is partially due to the lack of a distinct set of signs and symptoms, or an accepted cause. When Sharon reacts, she experiences several symptoms from seemingly every organ system, from brain fog to chest pain, diarrhoea, muscle aches, depression and odd rashes. The triggers for MCS generally are heterogeneous, sometimes extending beyond chemicals to food and even electromagnetic fields. Consistent physical findings and reproducible laboratory results have not been found and, as a result, people like Sharon not only weather severe, chronic illness but also scrutiny over whether their condition is ‘real’.

The first reported case of MCS was published in the Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine in 1952 by the American allergist Theron Randolph. Although he claimed to have previously encountered 40 cases, Randolph chose to focus on the story of one woman, 41-year-old Nora Barnes. She’s arrived at Randolph’s office at Northwestern University with a diverse and bizarre array of symptoms. A former cosmetics salesperson, she represented an ‘extreme case’. She was always tired, her arms and legs were swollen, and headaches plus intermittent episodes of blacking out ruined her ability to work. A doctor had previously diagnosed her with hypochondria, but Barnes was desperate for a ‘real’ diagnosis.

Randolph noted that the drive into Chicago from Michigan had worsened her symptoms, which spontaneously resolved when she checked into her room on the 23rd floor of a hotel where, Randolph reasoned, she was far away from the noxious motor exhaust filling the streets. In fact, in his report Randolph listed 30 substances that Barnes reacted to when touched (nylon, nail polish), ingested (aspirin, food dye), inhaled (perfume, the ‘burning of pine in fireplace’) and – presumably in a controlled clinical setting – been injected with (Benadryl, the opiate meperidine).

He posited that Barnes and his 40 other patients were sensitive to petroleum (and pine) products in ways that defied the classic clinical picture of allergies. That is, rather than an adverse immune response such as hives or rash, where the body is reacting to a particular antigen, patients with chemical sensitivities were displaying an intolerance. Randolph theorised that, just as people who are lactose-intolerant experience abdominal pain, diarrhoea and gas because of undigested lactose creating excess fluid in their GI tract, his patients were vulnerable to toxicity at relatively low concentrations of certain chemicals that they were unable to metabolise. He even suggested that chemical sensitivity research was being suppressed by ‘the ubiquitous distribution of petroleum and wood products’. MCS was not only a matter of scientific exploration but also of deep-seated corporate interest. Randolph concludes his report with his recommended treatment, which remarkably remains the current mainstream medical approach: avoidance of exposure.

As his professional reputation teetered, his popularity soared and patients flocked to his care

In this one-page abstract, Randolph cut the ribbon on the completely novel but quickly controversial field of environmental medicine. Nowadays, we hardly question the ties between the environment and wellbeing. The danger of secondhand smoke, the realities of climate change and the endemic nature of respiratory maladies like asthma are common knowledge. The issue was that Randolph’s patients lacked abnormal test results (specifically, diagnostic levels of immunoglobulin E, a blood marker that is elevated during an immune response). Whatever afflicted them was not conventional allergies, and thus conventional allergists resisted Randolph’s hypotheses.

Without historical precedence, Randolph was left in the dark. Why was MCS only now rearing its head? And he asked another, more radical question: why did this seem to be a distinctly American phenomenon? After all, the only other mention of chemical sensitivities in medical literature was in the American neurologist George Miller Beard’s textbook A Practical Treatise on Nervous Exhaustion (Neurasthenia) (1880). Beard argued that sensitivity to foods with alcohol or caffeine was associated with neurasthenia, a now defunct term used to describe the exhaustion of the nervous system propagated by the United States’ frenetic culture of productivity. Like Beard, Randolph saw chemical sensitivities as a disease of modernity, and conceived the origin as wear-and-tear as opposed to overload.

Randolph proposed that Americans, propelled by the post-Second World War boom, had encountered synthetic chemicals more and more in their workplaces and homes at concentrations considered acceptable for most people. Chronic exposure to these subtoxic dosages, in conjunction with genetic predispositions, strained the body and made patients vulnerable. On the back of this theory, Randolph developed a new branch of medicine and, with colleagues, founded the Society for Clinical Ecology, now known as the American Academy of Environmental Medicine.

As his professional reputation teetered, his popularity soared and patients flocked to his care. By the late-1980s, the number of clinical ecologists rivalled that of traditional allergists. Despite this growth in interest, researchers never identified blood markers in MCS patients, and double-blind ‘provocation’ trials found that people with MCS couldn’t differentiate between triggers and placebos. By 2001, a review in the Journal of Internal Medicine found MCS virtually non-existent outside of Western industrialised countries, despite the globalisation of chemical use, suggesting that the phenomenon was culturally bound.

MCS subsequently became a diagnosis of exclusion, a leftover label used after every other possibility was eliminated. The empirical uncertainty came to a head in 2021, when Quebec’s public health agency, the INSPQ, published an 840-page report that reviewed more than 4,000 articles in the scientific literature, concluding that MCS is an anxiety disorder. In medicine, psychiatric disorders are not intrinsically inferior; serious mental illness is, after all, the product of neurological dysfunction. But the MCS patients I spoke to found the language offensive and irresponsible. Reducing what they felt in their eyes, throats, lungs and guts to anxiety was not acceptable at all.

As a woman I will call Judy told me: ‘I would tell doctors my symptoms, and then they’d run a complete blood count and tell me I looked fine, that it must be stress, so they’d shove a prescription for an antidepressant in my face and tell me to come back in a year.’ In fact, because MCS is so stigmatising, such patients may never receive the level of specialised care they need. In the wake of her ‘treatment’, Judy was frequently bedbound from crushing fatigue, and no one took her MCS seriously. ‘I think a lot of doctors fail to understand that we are intelligent,’ she said. ‘A lot of us with chemical sensitivities spend a good amount of our time researching and reading scientific articles and papers. I probably spent more of my free time reading papers than most doctors.’

Judy grew up in Texas, where she developed irritable bowel syndrome and was told by doctors that she was stressed. Her 20s were spent in Washington state where she worked as a consultant before a major health crash left her bedbound for years (again, the doctors said she was stressed). A paint job for her first home, purchased in Massachusetts, gave her fatigue and diarrhoea. (Doctors: stress.) She used to browse the local art museum every Saturday, but even fumes off-gassing from the paintings irritated her symptoms. She visited every primary care doctor in the city as well as gastroenterologists, cardiologists, neurologists, endocrinologists and even geneticists. Most of them reacted the same way: with a furrowed brow and an antidepressant prescription in hand. ‘Not one allopathic doctor has ever been able to help me,’ Judy said, ‘and only one gynaecologist ever seemed like he was actually listening when I told him what my problem was.’

Asked if he had seen any patterns suggesting an organic cause of MCS, he responded: ‘Mould. Almost always’

Morton Teich is one of the few physicians who diagnoses and treats patients with MCS in New York. The entrance to his integrative medicine private practice is hidden behind a jammed door on the side of a grey-brick building on Park Avenue. Entering the waiting room, the first thing to catch my eye was the monstrous mountain of folders and binders precariously hugging a wall, in lieu of an electronic medical record. I half-expected Teich’s clinic to resemble the environmental isolation unit used by the allergist Randolph in the 1950s, with an airlocked entrance, blocked ventilation shafts and stainless-steel air-filtration devices, books and newspapers in sealed boxes, aluminium walls to prevent electromagnetic pollution, and water in glass bottles instead of a cooler. But there were none of the above. The clinic was like any other family medicine practice I had seen before; it was just very old. The physical examination rooms had brown linoleum floors and green metal chairs and tables. And there were no windows.

Although several of Teich’s patients were chemically sensitive, MCS was rarely the central focus of visits. When he introduced me as a student writing about MCS to his first patient of the day, a gasoline-intolerant woman who arranged her appointment to be over the phone because she was homebound, she admitted to never having heard of the condition. ‘You have to remember,’ Teich told me, ‘that MCS is a symptom. It’s just one aspect of my patients’ problems. My goal is to get a good history and find the underlying cause.’ Later, when I asked him whether he had observed any patterns suggesting an organic cause of MCS, he responded: ‘Mould. Almost always.’

Many people with MCS I encountered online also cited mould as a probable cause. Sharon told me about her first episode in 1998, when she experienced chest pain after discovering black mould festering in her family’s trailer home. In light of an unremarkable cardiac workup, Sharon’s primary care physician declared that she was having a panic attack related to the stress of recently undergoing a miscarriage. Sharon recognised that this contributed to her sudden health decline, but also found that her symptoms resolved only once she began sleeping outside her home at night.

She found recognition in medical books like Toxic (2016) by Neil Nathan, a retired family physician who argued that bodily sensitivities were the product of a hyper-reactive nervous system and a vigilant immune system that fired up in reaction to toxicities, much like Randolph had said. The conditions that Nathan describes are not supported by academic medicine as causes of MCS: mould toxicity, chronic Lyme disease, and mast cell activation syndrome all are subject to the same critique.

Motivated to find like-minded clinical ecologists, Sharon went to see William Rea, an ex-surgeon (and Teich’s best friend). Rea diagnosed her with MCS secondary to mould toxicity.

‘Mould is everywhere,’ Teich told me. ‘Not just indoors. Mould grows on leaves. That’s why people without seasonal allergies can become chemically sensitive during autumn.’ When trees shed their leaves, he told me, mould spores fly into the air. He suspected that American mould is not American at all, but an invasive species that rode wind currents over the Pacific from China. He mentioned in passing that his wife recently died from ovarian cancer. Her disease, he speculated, also had its roots in mould.

In fact, Teich commonly treats patients with nystatin, an antifungal medication used to treat Candida infections, a genus of yeast that often infects the mouth, skin and vagina. ‘I have an 80 per cent success rate,’ he told me. I was dubious that such a cheap and commonplace drug was able to cure an illness as debilitating as MCS, but I could not sneer at his track record. Every patient I met while shadowing Teich was comfortably in recovery, with smiles on their face and jokes flowing freely from their mouth, miles apart from the people I met in online support groups who seemed to be permanently in the throes of their illness. Even those of Teich’s patients not fully recovered broke my preconceived image of the MCS patient as frail and hyperbolic.

However, Teich was not practising medicine as I was taught it. This was a man who believed that the recombinant MMR vaccine triggered ‘acute autism’ in several of his paediatric patients – traditionally, an anti-science point of view. When one of his patients, a charismatic bookworm I’ll call Mark, arrived at an appointment with severe, purple swelling up to his knees and a clear case of stasis dermatitis (irritation of the skin caused by varicose veins), Teich reflexively blamed mould and wrote a prescription for nystatin instead of urging Mark to see a cardiologist. When I asked how a fungal infection in Mark’s toes could cause such a bad rash on his legs, he responded: ‘We have Candida everywhere, and its toxins are released into the blood and travel to every part of the body. The thing is, most people don’t notice until it’s too late.’

She became ill whenever she smelled fumes or fragrances, especially laundry detergent and citrus or floral scents.

Moulds and fungi are easy scapegoats for unexplainable illnesses because they are so ubiquitous in our indoor and outdoor environments.

A great deal of concern over mould toxicity (technical term, mycotoxicosis) stems from the concept of ‘sick-building syndrome’, in which visible black mould is thought to increase sensitivity and make people ill. This was true of Mark, who could point to the demolition of an old building across the street from his apartment as a source of mould in the atmosphere. Yet in mainstream medicine, diseases caused by moulds are restricted to allergies, hypersensitivity pneumonitis (an immunologic reaction to an inhaled agent, usually organic, within the lungs) and infection. Disseminated fungal infections occur almost exclusively in patients who are immunocompromised, hospitalised or have an invasive foreign body like a central line for delivery of medication. Furthermore, if the clinical ecologists are correct that mould like Candida can damage multiple organs, then it must be spreading through the bloodstream. But I have yet to encounter a patient with MCS who reported fever or other symptoms of sepsis (the traumatic, whole-body reaction to infection) as part of their experience.

Teich himself did not use blood cultures to verify his claims of ‘systemic candidiasis’ and instead looked to chronic fungal infection of the nails, common in the general population, as sufficient proof.

‘I don’t need tests or blood work,’ he told me. ‘I rarely ever order them. I can see with my eyes that he has mould, and that’s enough.’ It was Teich’s common practice to ask his patients to remove their socks to reveal the inevitable ridges and splits on their big toenails, and that’s all he needed.

Through Teich, I met a couple who were both chemically sensitive but otherwise just regular people. The wife, an upper-middle-class white woman I will call Cindy, had a long history of allergies and irritable bowel syndrome. She became ill whenever she smelled fumes or fragrances, especially laundry detergent and citrus or floral scents. Teich put both her and her husband on nystatin, and their sensitivities deadened dramatically.

What struck me about her case that differed from other patients with MCS was that Cindy was also on a course of antidepressants and cognitive behavioural therapy, the standard treatment for anxiety and depression, which Cindy had on her list of diagnoses. ‘It really helps,’ she said. ‘To cope with all the stress that my illness causes. You learn to live despite everything.’

In contemporary academic medicine, stress and anxiety cause MCS, but it is vital to remember that MCS can itself cause psychiatric symptoms. Teich later told me, unexpectedly, that he had no illusions about whether MCS is a partly psychiatric illness: ‘Stress affects the adrenals, and that makes MCS worse. The mind and the body are not separate. We have to treat the whole person.’

To understand this case, I also spoke with Donald Black, associate chief of staff for mental health at the Iowa City Veterans Administration Health Care and co-author of the article in UpToDate (the physician’s online bible for diagnosis and management) on idiopathic environmental intolerance that takes a uniform stance on MCS as a psychosomatic disorder. In 1988, when Black was a new faculty member at the University of Iowa, he interviewed a patient entering a drug trial for obsessive-compulsive disorder. He asked the woman to list her medications, and watched as she started unloading strange supplements and a book about environmental illness from her purse. The woman had been seeing a psychiatrist in Iowa City, Black’s colleague, who had diagnosed her with systemic candidiasis. Black was flummoxed. If that diagnosis was true, then the woman would be actively sick, not sitting calmly before him. Besides, it was not up to a psychiatrist to treat a fungal infection. How did he make the diagnosis? Did he do a physical or run blood tests? No, the patient told him, the psychiatrist just said that her symptoms were compatible with candidiasis. These symptoms included chemical sensitivities. After advising the patient to discard her supplements and find a new psychiatrist, Black made some phone calls and discovered that, indeed, his colleague had fallen in with the clinical ecologists.

Black was intrigued by this amorphous condition that had garnered an endless number of names: environmentally induced illness, toxicant-induced loss of tolerance, chemical hypersensitivity disease, immune dysregulation syndrome, cerebral allergy, 20th-century disease, and mould toxicity. In 1990, he solicited the aid of a medical student to find 26 subjects who had been diagnosed by clinical ecologists with chemical sensitivities and to conduct an ‘emotional profile’. Every participant in their study filled out a battery of questions that determined whether they satisfied any of the criteria for psychiatric disorders. Compared with the controls, the chemically sensitive subjects had 6.3 times higher lifetime prevalence of major depression, and 6.8 times higher lifetime prevalence of panic disorder or agoraphobia (the fear of situations, like being in public spaces, where escape in the event of panic-like symptoms is difficult); 17 per cent of the cases met the criteria for somatisation disorder, compared with 0 per cent of the controls. (Although in that last category, if you don’t think a disease is real, somatisation disorder would be the default.)

For him, there would always be patients searching for answers that traditional medicine could not satisfy

In my own review of the literature, it was clear that the most compelling evidence for MCS came from case studies of large-scale ‘initiating events’ such as the Gulf War (where soldiers were uniquely exposed to pesticides and pyridostigmine bromide pills) or the terrorist attacks on the US of 11 September 2001 (when toxins from the Twin Towers caused cancers and respiratory ailments for years). In both instances, a significant number of victims developed chemical intolerances compared with populations who were not exposed. From a national survey of veterans deployed in the Gulf War, researchers found that up to a third of respondents reported multi-symptom illnesses, including sensitivity to pesticides – twice the rate of veterans who had not deployed. Given that Gulf War vets experienced post-traumatic stress disorder at levels similar to those in other military conflicts, the findings have been used to breathe new life into Randolph’s idea of postindustrial toxicities leading to intolerance. The same has been said of the first responders and the World Trade Center’s nearby residents, who developed pulmonary symptoms when exposed to ‘cigarette smoke, vehicle exhaust, cleaning solutions, perfume, or other airborne irritants’ after 9/11, according to a team at Mount Sinai.

At the same time, Black, who doubts a real disease, has no current clinical experience with MCS patients. When I asked him how he managed his MCS patients, he admitted to not having any. In fact, outside of the papers he wrote more than 20 years ago, he had seen only a handful of MCS patients over the course of his career. Despite this, he had not only written the UpToDate article on MCS but also a guide in the online Merck Manual (aka the MSD Manual, the oldest continuously published English-language medical resource) on how to approach MCS treatment as a psychiatric disease. When I asked him if there was a way for physicians to regain the trust of patients who have been bruised by the medical system, he simply replied: ‘No.’ For him, there would always be a subset of patients who are searching for answers or treatments that traditional medicine could not satisfy. Those were the people who saw clinical ecologists, or who left society all together. (I talked with a number of patients in these situations, including one woman who lived in her van in the middle of the Arizona desert.) In a time of limited resources, these were not the patients on which Black thought psychiatry needed to focus.

It became clear to me why even the de facto leading professional on MCS had hardly any experience actually treating MCS. In his 1990 paper, Black – then a young doctor – rightly observed that

traditional medical practitioners are probably insensitive to patients with vague complaints, and need to develop new approaches to keep them within the medical fold. The study subjects clearly believed that their clinical ecologists had something to offer them that others did not: sympathy, recognition of pain and suffering, a physical explanation for their suffering, and active participation in medical care.

I wondered if Black had given up on these ‘new approaches’ because few MCS patients wanted to see a psychiatrist in the first place.

Both physicians on either side of the debate agreed that mental illness is a crucial part of treating MCS, with one believing that stress causes MCS while the other believes that MCS causes stress. To reconcile the views, I interviewed another physician, Christine Oliver, a doctor in occupational medicine in Toronto, where she has served on the Ontario Task Force on Environmental Health. Oliver believes that both stances are probably valid and true. ‘No matter what side you’re on,’ she told me, ‘there’s a growing consensus that this is a public health problem.’

Oliver represents a useful third position, one that takes the MCS illness experience seriously while hewing closely to medical science. As one of few ‘MCS-agnostic’ physicians, she believes in a physiological cause for MCS that we cannot know and therefore cannot treat directly due to lack of research. Oliver agrees with Randolph’s original suggestion of avoiding exposures, although she understands that this approach has resulted in traumatising changes in patients’ abilities to function. For her, the priority for MCS patients is a practical one: finding appropriate housing. Often unable to work and with a limited income, many of her patients occupy public housing or multi-family dwellings. The physician of an MCS patient must act like a social worker, providing education to landlords and other healthcare providers. Facilities such as hospitals, she feels, should be made more accessible by reducing scented cleaning products and soaps. Ultimately, finding a non-threatening space with digital access to providers and social support is the best way to allow the illness to run its course.

Whether organic or psychosomatic or something in between, MCS is a chronic illness. ‘One of the hardest things about being chronically ill,’ wrote the American author Meghan O’Rourke in The New Yorker in 2013 about her battle against Lyme disease, ‘is that most people find what you’re going through incomprehensible – if they believe you are going through it. In your loneliness, your preoccupation with an enduring new reality, you want to be understood in a way that you can’t be.’

A language for chronic illness does not exist beyond symptomatology, because in the end it’s symptoms that debilitate ‘normal’ human functioning. In chronic pain, analgesics can at least deaden a patient’s suffering. The same cannot be said for MCS symptoms, which are disorienting in their chaotic variety, inescapability and inexpressibility. There are few established avenues for patients to completely avoid triggering their MCS, and so they learn to orient their lives around mitigating symptoms instead, whether that is a change in diet or completely switching homes, as Sharon did. MCS comes to define their existence.

Sharon witnessed her network steadily expand as more older adults became isolated in quarantine

As a homebound person, Sharon’s ability to build a different life was limited. Outside, the world was moving forward, yet Sharon never felt left behind. What allowed her to live with chronic illness was not medicine or therapy, but the internet. On a typical day, Sharon wakes up and prays in bed. She wolfs down handfuls of pills and listens to upbeat music on YouTube while preparing her meals for the day: blended meats and vegetables, for easier swallowing. The rest of the day is spent on her laptop computer, checking email and Facebook, watching YouTube videos until her husband returns home in the evening. Then bed. This is how Sharon has lived for the past six years, and she does not expect different from the future. When I asked her if being homebound was lonely, I was taken aback at her reply: ‘No.’

In spite of not having met the majority of her 15 grandchildren (with two more on the way), Sharon keeps in daily contact with all of them. In fact, Sharon communicates with others on a nearly constant basis. ‘Some people are very much extroverts,’ Sharon wrote. ‘I certainly am. But there are also people who need physical touch … and I can understand why they might need to see “real people” then … but it’s very possible to be content with online friends. This is my life!’ The friendships that Sharon formed online with other homebound people with chronic illnesses were the longest-lasting and the most alive relationships she had ever known. She had never met her best friend of 20 years, their relationship existed completely through letters and emails up until two years ago when the friend died. That ‘was very hard for me’, Sharon wrote.

As expected, the pandemic changed very little of Sharon’s life. If anything, COVID-19 improved her situation. In the same way that Sharon was forced to drastically alter her life to minimise her MCS symptoms, other Americans struggled to re-invent their modes of communication to temper the spread of the virus while maintaining relationships. Sharon’s local church live-streamed Sunday service, telehealth doctor appointments became the default, YouTube exploded in content, and staying indoors was normalised. Sharon witnessed her network steadily expand as more older adults became isolated in quarantine.

Using her years of experience in coping with MCS, Sharon felt empowered by the pandemic to become an informal leader in the online MCS community. She regularly reached out to strangers who joined her Facebook group, hearing their stories and sharing her own.

People within the online MCS community call themselves ‘canaries’, a species historically used as sentinels in coal mines to detect toxic levels of carbon monoxide. With a higher metabolism and respiratory rate, the small birds would theoretically perish before the less-sensitive human miners, providing a signal to escape. The question for people with MCS is: will anyone listen?

‘Us canaries,’ said a woman named Vera who was bedbound from MCS for 15 years after a botched orthopaedic surgery, ‘we struggle and suffer in silence.’ Now, in the information age, they have colonised the internet to find people like themselves. For our part, we must reimagine chronic illness – which will become drastically more common in the aftermath of the pandemic – where what matters to the patient is not only a scientific explanation and a cure, but also a way to continue living a meaningful life. This calls into action the distinction that the psychiatrist and anthropologist Arthur Kleinman made in his book The Illness Narratives (1988) – between illness and disease. Whereas a disease is an organic process within the body, illness is the lived experience of bodily processes. ‘Illness problems,’ he writes, ‘are the principal difficulties that symptoms and disability create in our lives.’

By centring conversations about MCS on whether or not it is real, we alienate the people whose illnesses have deteriorated their ability to function at home and in the world. After all, the fundamental mistrust does not lie in the patient-physician relationship, but between patients and their bodies. Chronic illness is a corporeal betrayal, an all-out assault on the coherent self. Academic medicine cannot yet shed light on the physiological mechanisms that would explain MCS. But practitioners and the rest of society must still meet patients with empathy and acceptance, making space for their narratives, their lives, and their lived experience in the medical and wider world.