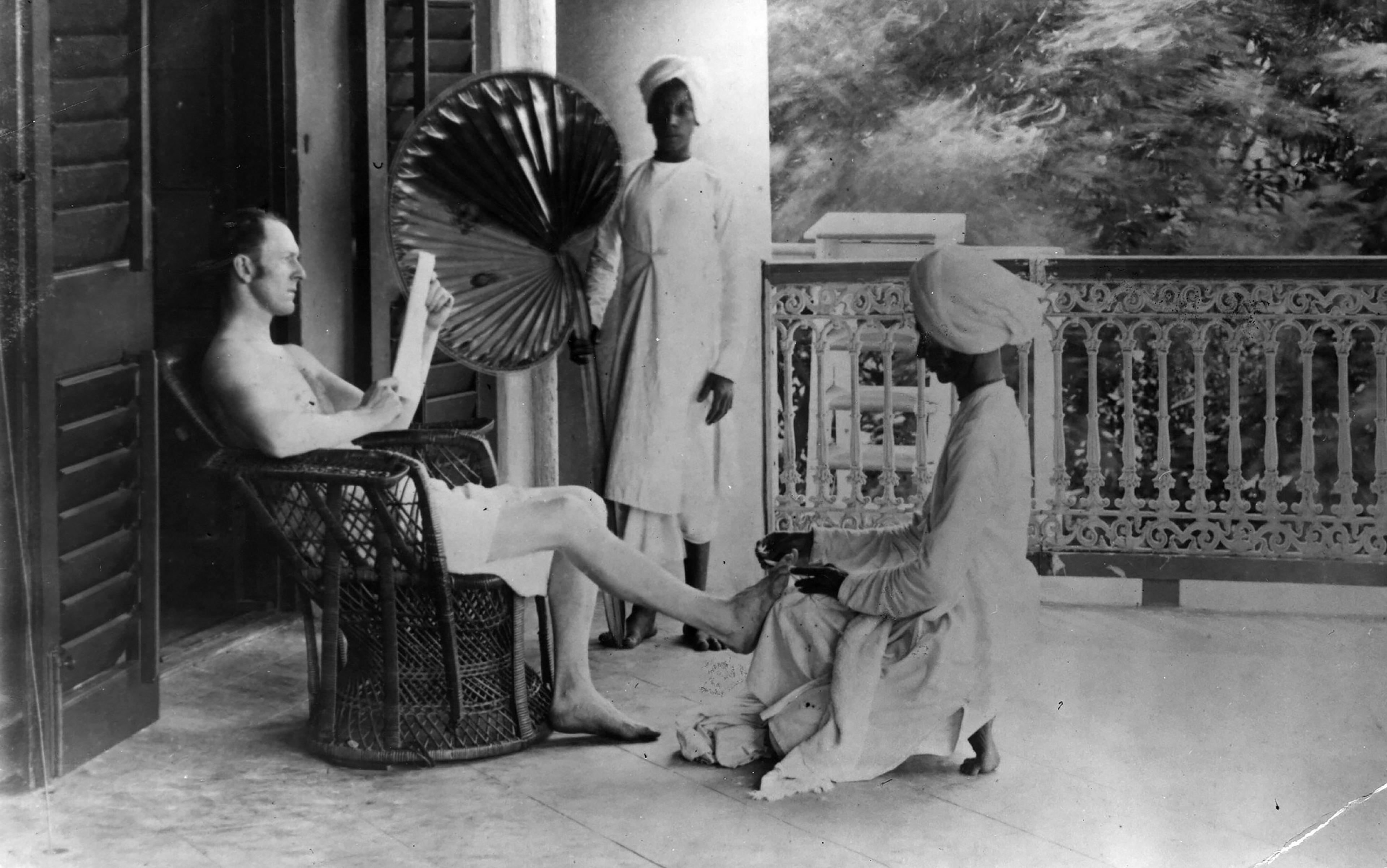

Every state needs to know about the people it rules. Censuses, property surveys and tax records are familiar and tangible expressions of the state’s need to maintain power by accumulating knowledge. This is not just a matter of tedious bureaucratic record-keeping: especially when confronted with unfamiliar problems, states often turn to cutting-edge technologies and forms of expertise to make sense of the populations under their authority. In the early 20th-century Age of Empire, when European colonies stretched across the world, psychoanalysis was the novel technique of the moment. In an attempt to better understand their colonial subjects in those years, officials in the British empire undertook a curious and little-known research project: to collect dreams from the people of South Asia, Africa and the Pacific. The results were not what they expected.

Take, for example, the dream of Lhuzekhu, a man from the Naga Hills of Northeastern India who worked as an interpreter for the colonial administration. Lhuzekhu’s boss, a British district officer, recorded this dream in 1924:

I went alone down to the school. An elephant with no one on its back came up from the bazaar. I felt it was yours. I was frightened it might hurt me and threw a stone at it … Then I found myself in my house with my family … We all sat round the fire. There was a sudden gale of wind. I held the post fearing my house would be blown over. The gale stopped. I looked at all my posts and especially at the carved one in front of the door, and said: ‘If it had not been for this post, my house would have fallen and I should have had a lot of trouble.’

Lhuzekhu’s dream was among hundreds collected from across the British empire – from the Indian subcontinent, Nigeria, Uganda, Australia, the Solomon Islands and elsewhere – on the instructions of an anthropologist at the London School of Economics (LSE) named Charles Gabriel Seligman. Seligman was a longtime adviser to colonial governments, which funded his research and helped to train colonial officials at the LSE. Seligman made his career as a physical anthropologist at the height of racialist science. That meant defining human groups on the basis of physiognomy and locating them in evolutionary hierarchies. Seligman was, in short, an imperialist and a classifier par excellence. So what did he hope to accomplish by amassing dreams such as Lhuzekhu’s?

Building a database of colonial dreams was a quixotic, even utopian, project. Seligman, a Sigmund Freud enthusiast, wanted to see what sort of information the powerful new tool of psychoanalysis could generate when confronted with the diverse cultures under British rule. He also felt constrained by older techniques in psychology, such as measurements of reaction time to visual stimuli, which were long seen as the only kind of mental experience researchers could reliably capture. Seligman came to believe that these methods brought mere technical precision without the depth or complexity of inner life. Dream research would show whether Freudianism could travel across cultural boundaries and return with richer, more textured portraits of the mind. It was an unconventional move, not only because Freud’s theories remained controversial in scientific circles, but also because most observers in the West still clung to the stereotype of alien and inscrutable minds in supposedly ‘primitive’ societies.

Like any good Freudian, Seligman knew that the meaning of dreams could be elicited only through the act of interpretation; simply recording the twists and turns of the narrative was not enough. So he instructed his dream-collecting agents – an assortment of colonial officials and anthropologists stationed across the world – to question their informants about the reactions and associations that arose as they described their dreams. When he turned to analyse Lhuzekhu’s dream, for instance, Seligman began with Lhuzekhu’s own words: ‘The excellence and strength of my carved post means I shall have fine sons and daughters.’ Picking up on the ‘phallic’ symbolism of this phrase, Seligman thought it revealed that Lhuzekhu’s sense of self was rooted in ‘strength and reproduction’.

Perhaps, then, Seligman could file this case in a growing pile of evidence for the universal validity of Freudian theory? The logic of wish-fulfilment appeared again and again in dreams from across the world: death wishes in West Africa; incestuous desires in dreams in the Solomon Islands; fantasies of aggression against authority figures in Australia. On the other hand, a good deal of evidence pointed in the opposite direction. Informants on at least three continents reported that the stages of sexual development that Freud made famous – oral, anal, genital – were nowhere to be found; children did not pass through a latency period, for instance, or a phase of fascination with excretory functions. Seligman’s dream-collectors in the Naga Hills and in Nigeria even gainsaid the relevance of such fundamental concepts as libido and repression. Sexual mores were so much less restrictive than in the West, they reported, that unconscious minds there were much less intent on subverting them.

In that case, perhaps Lhuzekhu’s dreams could be impressed into a story about the peculiarities of ‘savage’ or ‘primitive’ minds? But here too, Seligman’s data overwhelmed the possibility of neat interpretations. To establish a kind of control group for his cross-cultural analysis, Seligman used a BBC radio broadcast in 1931 to solicit dreams and auto-interpretations from ordinary people in Britain. He found that both the symbols in dreams and their associated emotional states were almost universally shared. In Britain and the colonies alike, for instance, anxiety dreams often featured the unsettling image of teeth coming loose in one’s mouth; pleasant, vaguely erotic dreams, by contrast, frequently involved visions of flying through the air. Questioning the Freudian paradigm that prompted him to gather dreams in the first place, Seligman instead flirted with Jung’s theory of a ‘collective unconscious’ – a storehouse of myths, images and memories inherited by all human beings.

Whether in Freudian or Jungian perspective, Seligman saw that the colonial subjects’ dreams pointed in the direction of one unexpected conclusion. As he put it in 1932 : ‘The savage mind and the mind of Western civilised man are essentially alike.’ While symbols in dreams offered some support for this vision of a universal psychology, the significance attached to dreams in waking life might have offered even more. Going over the British submissions for his BBC broadcast, Seligman – who, like other anthropologists, had long observed that people in other cultures interpreted dreams as prophecies or omens of future events – discovered that ‘Western civilised man’ did exactly the same thing. Several correspondents disclosed an interest in spiritualism, telepathy, astrology; several more related prophetic dreams – dreams that they insisted had foretold the future in their own lives. When Seligman tried to offer rational explanations for their premonitions, they refused to accept them. One woman angrily wondered why anyone would disclose her dream to a stranger if not to receive a prophecy in return. ‘The experiment is interesting,’ Seligman sighed, ‘as showing the very large proportion of people who considered dreams as prophetic.’

The father figure who inspired aggressive feelings was almost always a British official or missionary

In short, Seligman struggled to impose meaning on his unusual archive. When he tried to establish universalities, exceptions and contradictions proliferated. And when he tried to draw sharp distinctions between the minds of Britons on the one hand, and colonial subjects on the other, commonalities asserted themselves. Even in a situation where researchers held all the power – with the authority of the imperial state behind them, and an elaborate theoretical structure setting the terms of the encounter – their subjects did not always follow the script.

Which brings us back to Lhuzekhu. As Seligman began to wonder about the universality of Freudianism, he noticed that the Oedipus complex took a particular form in the dreams of his colonial subjects: the father figure who inspired aggressive feelings was almost always a British official or missionary. That Lhuzekhu perceived the elephant as the property of the district officer, then threw a stone at it, revealed undercurrents of hostility which could not be expressed openly. This insight caused the remaining pieces of the puzzle to fall into place. Seligman glossed the shift to a domestic setting as an ‘escape to the mother’; the wind threatening to topple his home as the earth-shaking trauma visited by imperial rule. Lhuzekhu’s boast about ‘fine sons and daughters’ became a fantasied resolution. Seligman saw this flourish as confirmation that Lhuzekhu wanted to usurp the district officer’s paternalistic authority. In other words, Seligman concluded: ‘He lives his father hostility and becomes the father himself.’ Outwardly deferential, Lhuzekhu in fact resented the seizure of power by British imperialists, and longed to topple them from their perch.

Seligman’s interpretation represented a new twist on the Freudian idea of politics as a father-son struggle. The oppressive force in this case was neither a class nor a generation but the British empire itself: a regime founded on violence and hostile to dissent. In this context, dreams offered a glimpse of the tensions that were integral to an undemocratic and hierarchical society, but which remained unsayable – at least to the British.

Even among Seligman’s relatively small sample of subjects, Lhuzekhu’s anger and frustration were not unique. Thousands of miles away, in Uganda, an African working for the colonial administration also suffered nightmares about the authority figures in his life. Philipo Oruro, a ‘native chief’ or Jago, shared his dreams with an anthropologist working for Seligman. Oruro’s nightmares suggested that he was terrified of British officials and missionaries. Whether the violent assaults in his dreams offered a literal accounting of reality or a figurative representation of emotional truth is unclear. But there is no doubt that Oruro experienced imperial rule as an ongoing trauma and a source of wrenching anxiety.

In Oruro’s dreams, British authorities inflicted unexplained, unavoidable and humiliating violence:

Bwana D C [the district commissioner] beat the behind of Won pacho Asanasio Pule [a village chief] hard. Then he gave him to Won amagoro Etum [a more powerful chief] to beat. When the stick broke in pieces, Etum went to fetch another and continued to beat him for a long time. Then I said: ‘Well, when are you going to leave off?’ Bwana said: ‘Not yet sufficient.’

Four nights later, Oruro dreamt that another Bwana (a Swahili honorific that could have signified any European figure) threatened to give him 10 strokes with a cane for breaking through the fence behind the school. Three weeks after that, Oruro dreamt that yet another Bwana, apparently a missionary, scolded him sharply: ‘Not in the slightest do you help me in my work.’ Oruro humbled himself to the point of prostration – ‘Bwana, I am still fresh, I have only just started, come teach me’ – but to no avail. After showering praise on one of Oruro’s rivals, the man called Bwana Cox drove Oruro from the house and threatened to beat him into submission.

When, a quarter-century later, Frantz Fanon analysed the dreams of Algerians living under French colonialism, he noted that many involved scenes of running and jumping: expressions of the longing for physical freedom, for the ability to move without fear, that the reality of colonial rule denied them. For Oruro, by contrast, even sleep did not provide a respite from the weight of oppression – a striking revelation. Yet beyond acknowledging ‘the very large part played by white officials’ in these dreams, Seligman seemed unsure what to make of them. They focused attention on a dark side of empire that he was unwilling, or unable, to acknowledge.

It might be tempting to dismiss Seligman’s experiment as an insignificant exercise in eccentricity: a curiosity cabinet with little relevance to the business of running an empire. Can its aims, and its breakdowns, really tell us anything about the way that states try to know their subjects? In fact, the dream project was neither so unusual nor so apolitical as it might seem. Particularly after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, British officials across the empire shared two related preoccupations: the fear of further uprisings, and the conviction that the inner lives of their subjects – their beliefs, their attitudes, their emotions – were exceedingly difficult to determine. For British officials, these anxieties surged anew in the aftermath of the First World War when an outbreak of rebellion from Ireland to Egypt to Iraq to India forced Britons to confront the depth and intensity of resistance to their rule. Against this alarming – for the British – backdrop, Seligman was not alone in seeing psychoanalysis as a potentially cutting-edge instrument of political intelligence.

In the 1930s, in the colony of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), a British education official psychoanalysing African students passed along his observations to a colonial administrator. The findings stirred concern: ‘The young men concerned showed unmistakable signs that they were on the point of plunging into subversive activities.’ In Nigeria, a protégé of Seligman’s undertook a Freudian-tinged study of women who had taken part in a major uprising against British rule. Arguing that the boom-and-bust cycles of the colonial economy and the repressive actions of the colonial military had unleashed pathological levels of resentment, she warned that the threat of rebellion remained strong. In the Gold Coast (now Ghana), another Seligman acolyte collecting dreams and free associations from indigenous sub-rulers also picked up on powerful feelings of aggression against British authority. It had gotten to the point, he observed, that the British represented ‘a common enemy’ among Africans, like ‘the Jew in Hitler’s Germany’.

The same studies that gave evidence of indigenous pathology pointed to the damage done by British rule

The common thread running through all the accounts was a twist on the Oedipal story. The oppressive patriarch, a largely fantasied figure in the European context, was here embodied in the very real force of the ‘white man’ and the colonial state behind him. This was a strikingly deromanticised vision of empire, in which only habits of deference and fear of reprisal constrained the urge to throw off tyrannical shackles. Seligman had, it turned out, chronicled the psychic wounds of colonialism, revealing a political order fundamentally at odds with Britain’s self-understanding. The question that emerged was whether British rulers could defuse the challenges that this sentiment posed to their rule before it engulfed them. Such was the pragmatic logic that drove British efforts to map the unconscious minds of their colonial subjects.

After 1945, as another wave of anticolonial unrest loomed, the machinery of psychoanalytic surveillance came to life once again. In Malaya, Communist rebels captured by British security forces faced questions devised by social scientists. The insurgents were asked about their childhood experiences, family relationships, social connections, gambling habits, and feelings of shame and envy – all in an effort to map the unconscious origins of rebellion. In Jamaica, a study sponsored by the Colonial Office amassed psychological data from children and adults across the island: life histories, dreams, and the results of so-called projective tests (including the Rorschach inkblot test). In Uganda, Colonial Office researchers used questionnaire data to trace the connections between life experiences and support for nationalist movements. And so on.

Did colonial officials get what they wanted from these growing collections of Freudian data? Some results, to be sure, ended up in tendentious arguments portraying anticolonial politics as the product of mental illness. The language of ‘frustration-aggression’ reactions and ‘deculturation’ disorders allowed some British officials to suggest that calls for independence derived from inchoate expressions of anger and immaturity. Once again, however, a clear-cut vindication of empire through expert knowledge proved elusive. The same studies that furnished evidence of indigenous pathology could not avoid pointing to the damage inflicted by British rule: the crushing racial hierarchies, the lack of economic opportunities, the weirdly Anglocentric schooling. Some researchers even suggested that imperialism, not anticolonial nationalism, was the real mental disorder; they explained the behaviour of British colonialists in terms of status anxieties, sexual hang-ups, and feelings of insecurity.

In the end, it is perhaps the British government’s decades-long support for research into unconscious minds that is most revealing. Lacking the mechanisms that register public opinion in democratic societies – elections, protests, press criticism – and confronting immense cultural differences to boot, British imperial rulers fretted over what Africans, Asians and West Indians were thinking. The British sensed their ignorance, and they felt vulnerable, a position that made the tools of psychoanalysis irresistible. The trouble was not that these tools failed on their own terms, but that they failed to tell imperial rulers what they wanted to hear. No matter how many times such experiments as Seligman’s exploded the myth of docile and contented subjects, discovering a more congenial version of the so-called ‘native mind’ remained a fantasy too enticing to pass up.