Stowaway Perce Blackborow and Mrs Chippy aboard Shackleton’s Endurance, 1914-1917. Photo courtesy Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge

Whatever currency drives adventure, whether fame or fortune, a stowaway trying to cash in on glory often features in the story. Sometimes, they’re escaping a bad situation; sometimes, they’re wannabe explorers themselves; and sometimes they’re just wild and crazy. Throughout history, stowaways have tracked society’s most famous explorers, and by extension they invite all of us to imagine ourselves as great explorers too.

The first stowaway of note was the 16th-century Spanish conquistador and explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa, who traversed America. Balboa travelled from Spain to the New World around 1500, and after looking around, chose to stay put on the island of Hispaniola. By 1509, when he was in his mid-30s, he was in a funding crunch. Escaping his Santo Domingo creditors, the desperate pig farmer stowed away in a flour barrel on a supply ship headed to San Sebastián de Urabá in Panama. He must have charmed the angry captain because he was forgiven and welcomed aboard. San Sebastián de Urabá was deserted and it was Balboa who suggested a new colony of Darién – and he even became its temporary governor before becoming the governor of nearby Veragua. Enmeshed with indigenous people, he heard them tell rumours of a great sea. With Native Americans as his guides, Balboa went to a mountain where he could gaze out on the Pacific Ocean, unknown to Europeans. It was a thrilling discovery for Spain, but the former stowaway’s luck ends there. Another Spanish governor replaced him, decapitating him and sticking his head on a pike in 1519.

Stowaways by sea were common for centuries, but 1910 brought the first attempt by air: during test trials of the dirigible balloon Parseval VI, a German worker named Haas crept under a tarpaulin covering the benzene fuel. The worker made worldwide headlines because there’s nothing like an airship stowaway to whip up interest.

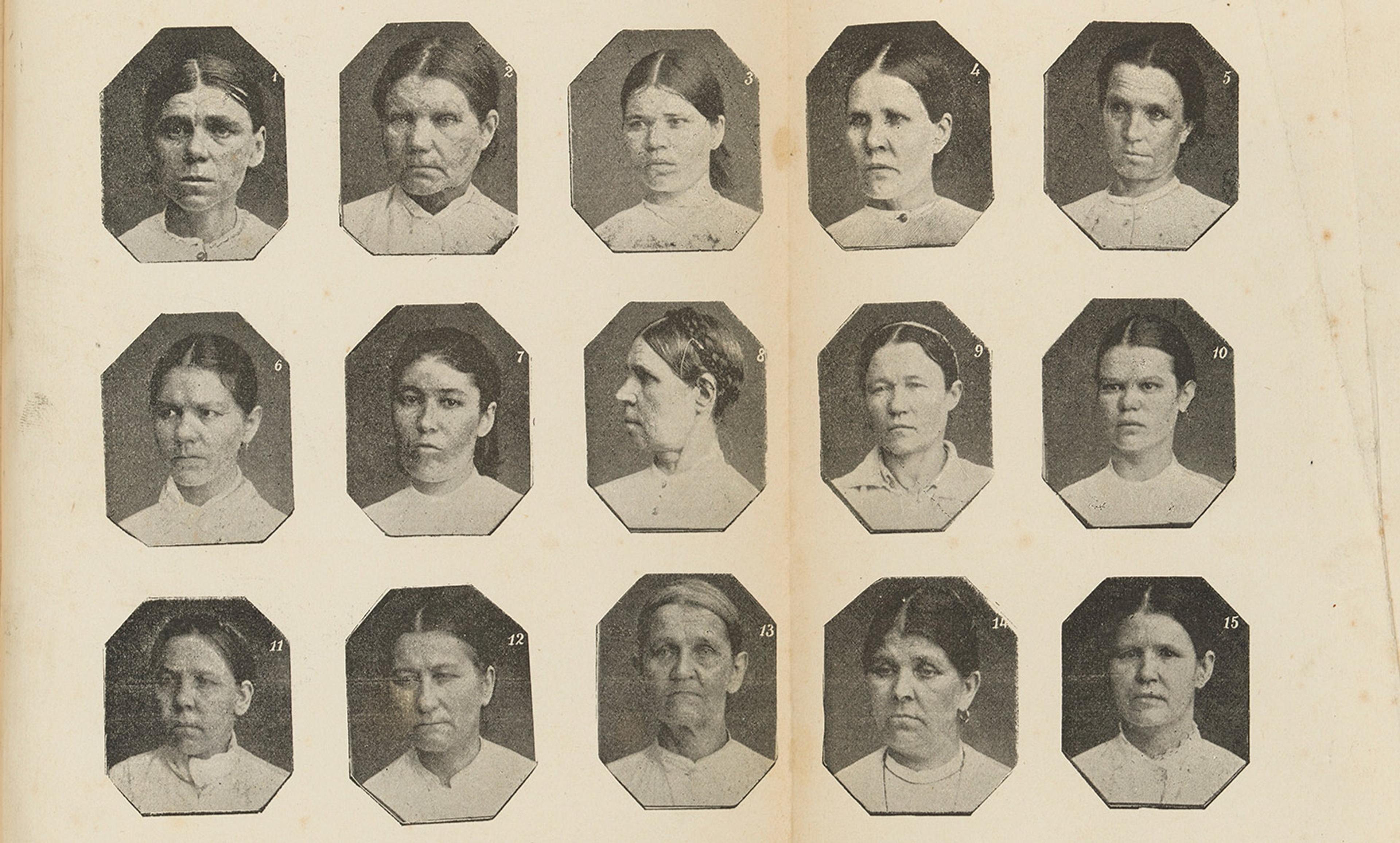

Then in 1914, the British explorer Ernest Shackleton had a Welsh stowaway named Perce Blackborow on his ship, the Endurance, heading to the Antarctic. Blackborow had interviewed with Shackleton for crew but was rejected because he was too young. Ultimately, he was extracted from a cramped locker and revealed to officers to be the 28th man in the Weddell Sea Party. Shackleton seethed, saying: ‘Do you know that on these expeditions we often get very hungry, and if there is a stowaway available he is the first to be eaten?’ The stowaway’s quick reply was: ‘They’d get a lot more meat off you, sir,’ which got a big smile from the angry explorer and helped Blackborow stay on ship. He was considerably less cheeky when he developed gangrene at Elephant Island and had his toes amputated.

History saw a glut of young stowaways in the Roaring 1920s, each one fuelling the public imagination. Arthur Schreiber, a Jewish kid from Portland in Maine, who made a living singing at house parties, hit the news in 1929. Wearing his brother’s army uniform, he arrived at Old Orchard Beach, which was overflowing with people there to see the start of a transatlantic race to Rome. Most of the crowd was huddled in front of a Bellanca J Model plane called the Green Flash, the American entry. So Schreiber stowed away in a Bernard 191 monoplane called the Yellow Bird, manned by the French. Schreiber, who weighed down the craft, emerged 20 minutes after takeoff. The pilots considered tossing him into the ocean but magnanimously let him join the crew, hoping for the best. Alas, their gas ran out. Instead of landing in Rome, the pilot, Jean Assolant, forced his monoplane down in Santander in Spain. ‘I had not calculated for the extra weight in the amount of gasoline carried,’ he said at a conference, after landing. If he had once been angry at his unexpected guest, he now adored him. ‘He shared our risks and he is one of us now. We will see that he sees all there is in Paris, and then send him home on steamship.’ Schreiber eventually returned to the US in the giant steamship the Leviathan in fine-cut French clothing, and was met in quarantine by his agitated father.

The most charming stowaway tale hails from 1934 and the Great Depression, when an eight-year-old moppet named Carroll L Wainwright Jr, a great-grandson of the financier Jay Gould, hid on the SS Queen of Bermuda. He emerged only because he was hungry and was quickly nicknamed ‘The Silk-Stockinged Stowaway’ by reporters happy to push upbeat news.

The story of the stowaway offers another take on history, which most often is told over the shoulders of the powerful and well-known. The stowaway is a footnote who challenges the powerful with uncontained desire, an everyman who makes us think: ‘Hey, that could be me.’

There’s no reason to think that the practice will stop, even on the journey to space, though at first it might be tough. Kim Binsted, principal investigator at HI-SEAS, a habitat on the slopes of Hawaii’s Mauna Loa volcano that simulates the experience of a human habitat on Mars, told me that ‘stowing away on an early exploration mission would be both difficult and probably suicidal. To begin with, on early missions, it’s hard to even imagine where a stowaway would stow. Those ships are going to be small.’

We think of monoplanes as mission critical, but early space ventures could have even more exacting limits. It’s hard to hide in a cramped spaceship. You’ve got to be really small or the crew has to be really dumb. So the next frontier might prove a little tough for a trickster. As Binsted explained:

The additional weight of the stowaway’s body would probably be detected, and if not, could throw off some pretty important trajectory calculations. Then, if the stowaway made it through takeoff, they would consume extra resources (fuel, air, water, food) needed to keep everyone alive. Let’s say the original crew was meant to be six people. Now everyone has to survive on six sevenths [of the] rations – and if the stowaways don’t reveal themselves, the crew could just run out six sevenths of the way there!

One stowaway on an early mission to space might mean everyone dies. Systems for recycling air and water ‘would be overloaded, and might function poorly or break altogether, even if everyone consumes conservatively’, Binsted said.

Yet this plugged-in scientist would not write off the possibility of interplanetary stowaways as time goes on. ‘Once we get to larger crews with a hundred or more, stowing away becomes more feasible, as the systems-level impact of one more person would then fall within anticipated margins,’ she explained.

Even if they are not on the official to-do list of the world’s mission-driven space programmes, there will likely be stowaways across the Universe as we begin to explore and settle new worlds. One day, after all, 2018 will be ancient history.