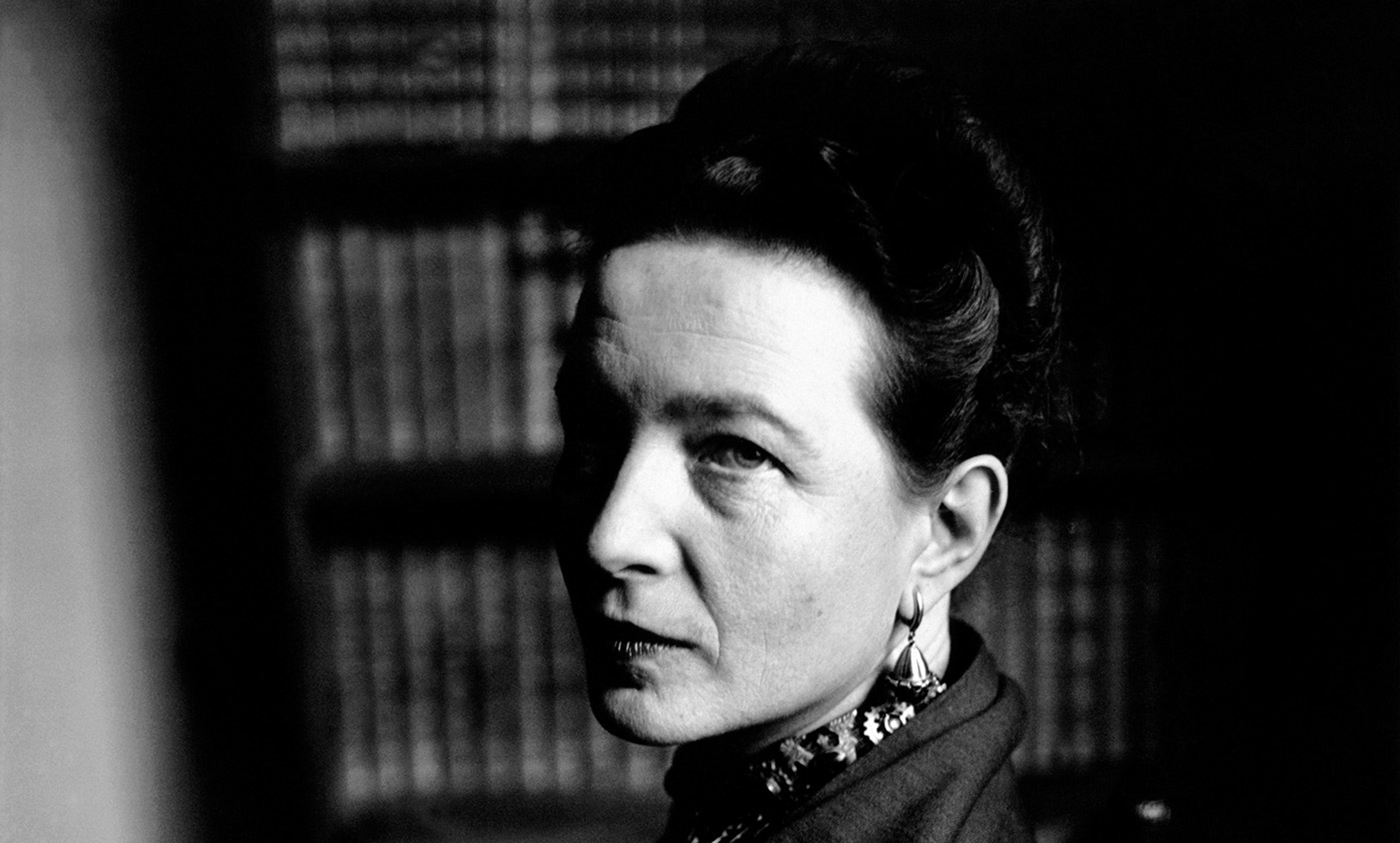

Simone de Beauvoir in Paris in 1949. Elliot Erwitt/Magnum

Simone de Beauvoir is rightly best known for declaring: ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.’ A less well-known facet of her philosophy, particularly relevant today, is her political activism, a viewpoint that follows directly from her metaphysical stance on the self, namely that we have no fixed essences.

The existential maxim ‘existence precedes essence’ underpins de Beauvoir’s philosophy. For her, as for Jean-Paul Sartre, we are first thrown into the world and then create our being through our actions. While there are facts of our existence that we can’t choose, such as being born, who our parents were, and our genetic inheritance, we shouldn’t use our biology or history as excuses not to act. The existential goal is to be an agent, to take control over our life, actively transcending the facts of our existence by pursuing self-chosen goals.

It’s easy to find excuses not to act. So easy that many of us spend much of our lives doing so. Many of us believe that we don’t have free will – even as some neuroscientists are discovering that our conscious will can override our impulses. We tell ourselves that our vote won’t make any difference, instead of actively shaping the world in which we want to live. We point fingers at Facebook for facilitating fake news, instead of critically assessing what we’re reading and reposting. It’s not just lazy to push away responsibility in such ways, but it’s what de Beauvoir called a ‘moral fault’.

Since we’re all affected by politics, if we choose not to be involved in creating the conditions of our own lives this reduces us to what de Beauvoir called ‘absurd vegetation’. It’s tantamount to rejecting existence. We must take a side. The problem is, it’s not always clear which side we ought to choose. Even de Beauvoir failed to navigate through this question safely. She adopted questionable political stances: she once, for example, dismissed Chairman Mao – responsible for the murder of over 45 million people – as being ‘no more dictatorial’ than Franklin D Roosevelt. De Beauvoir’s philosophy of political commitment has a dark side, and she personally made some grave errors of judgement, yet within her philosophy, there’s an opening to address this issue.

In The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947) she argues that to be free is to be able to stretch ourselves into an open future full of possibilities. Having this kind of freedom may be dizzying, but it doesn’t mean we get to do whatever we like. We share the earth, and have concern for one another; if we respect freedom for ourselves, then we should respect it for others, too. Using our freedom to exploit and oppress others, or to support the side that promotes such policies, is inconsistent with this radical existential freedom.

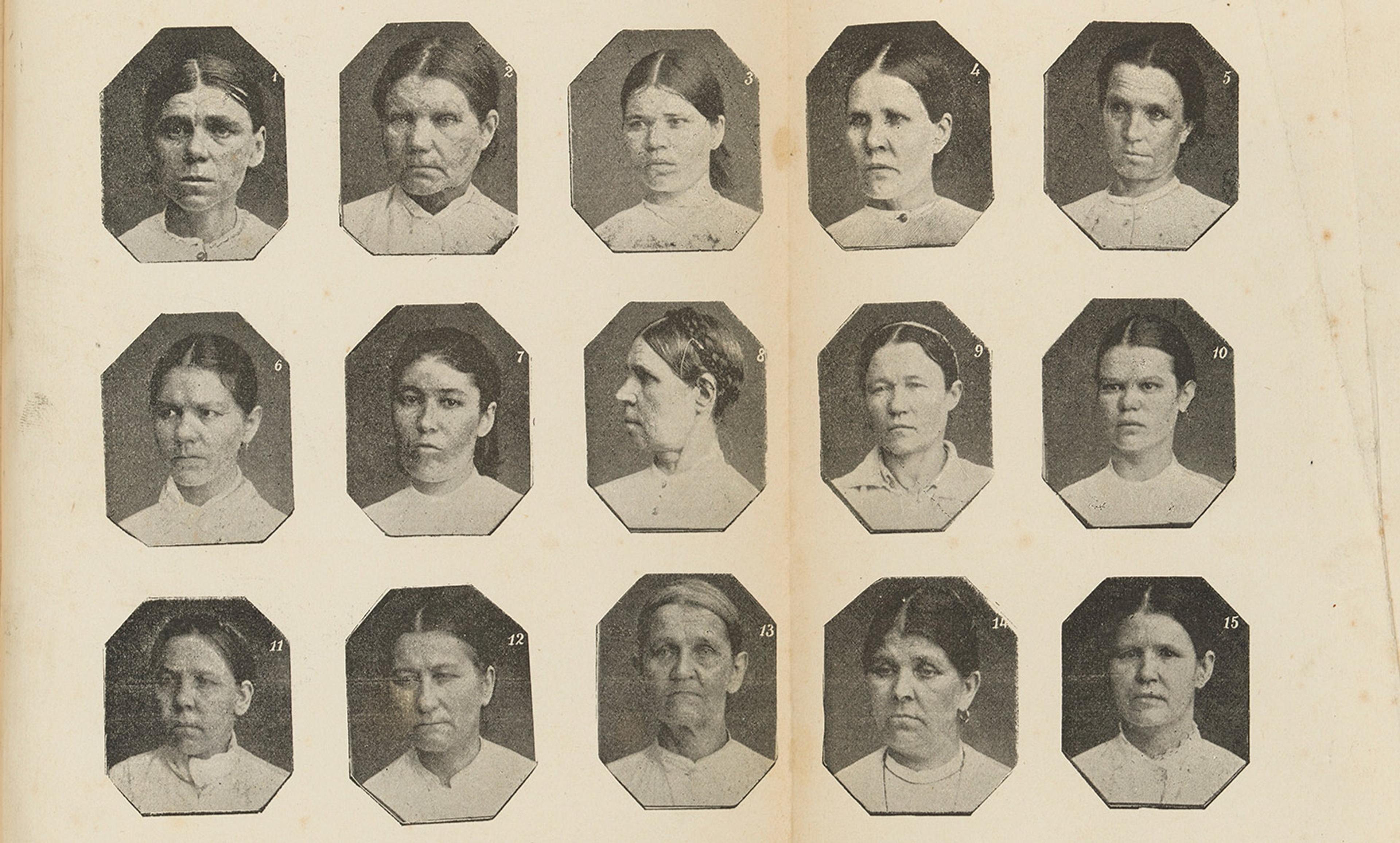

With oppressive regimes, de Beauvoir acknowledged that individuals usually pay a high price for standing up to dictators and the tyranny of the majority, but demonstrated concretely – through her writing and political engagement – the power of collective action to bring about structural change. An intellectual vigilante, de Beauvoir used her pen as a weapon, breaking down gendered stereotypes and challenging laws that prohibited women from having control over their own bodies. She authored and signed the Manifesto of the 343 in 1971, which paved the way for birth control and abortion in France. Her most famous work, The Second Sex (1949), sparked a new wave of feminism across the world.

Today more than ever it’s vital to recognise that freedom can’t be assumed. Some of the freedoms that de Beauvoir fought so hard for in the mid-20th century have since come under threat. De Beauvoir warns that we should expect appeals to ‘nature’ and ‘utility’ to be used as justifications for restrictions on our freedom. And she has been proved correct. For example, the argument that Donald Trump and others have used that pregnancy is inconvenient for businesses is an implicit way of communicating the view that it is natural and economical for women to be baby-making machines while men work. However, de Beauvoir points out ‘anatomy and hormones never define anything but a situation’, and making birth control, abortion, and parental leave unavailable closes down men’s and women’s ability to reach beyond their given situations, reinforcing stereotypical roles that keep women chained to unpaid home labour and men on a treadmill of paid labour.

In times of political turmoil, one may feel overwhelmed with anxiety and can even be tempted with Sartre to think that ‘hell is other people’. De Beauvoir encourages us to consider that others also give us the world because they infuse it with meaning: we can only make sense of ourselves in relation to others, and can only make sense of the world around us by understanding others’ goals. We strive to understand our differences and to embrace the tension between us. World peace is a stretch, since we don’t all choose the same goals, but we can still look for ways to create solidarities – such as by working to agitate authoritarians, to revolt against tyrants, to amplify marginalised voices – to abolish oppression. Persistence is essential since, as de Beauvoir says, ‘One’s life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of others, by means of love, friendship, indignation and compassion.’ De Beauvoir is surely right that this is the risk, the anguish, and the beauty of human existence.