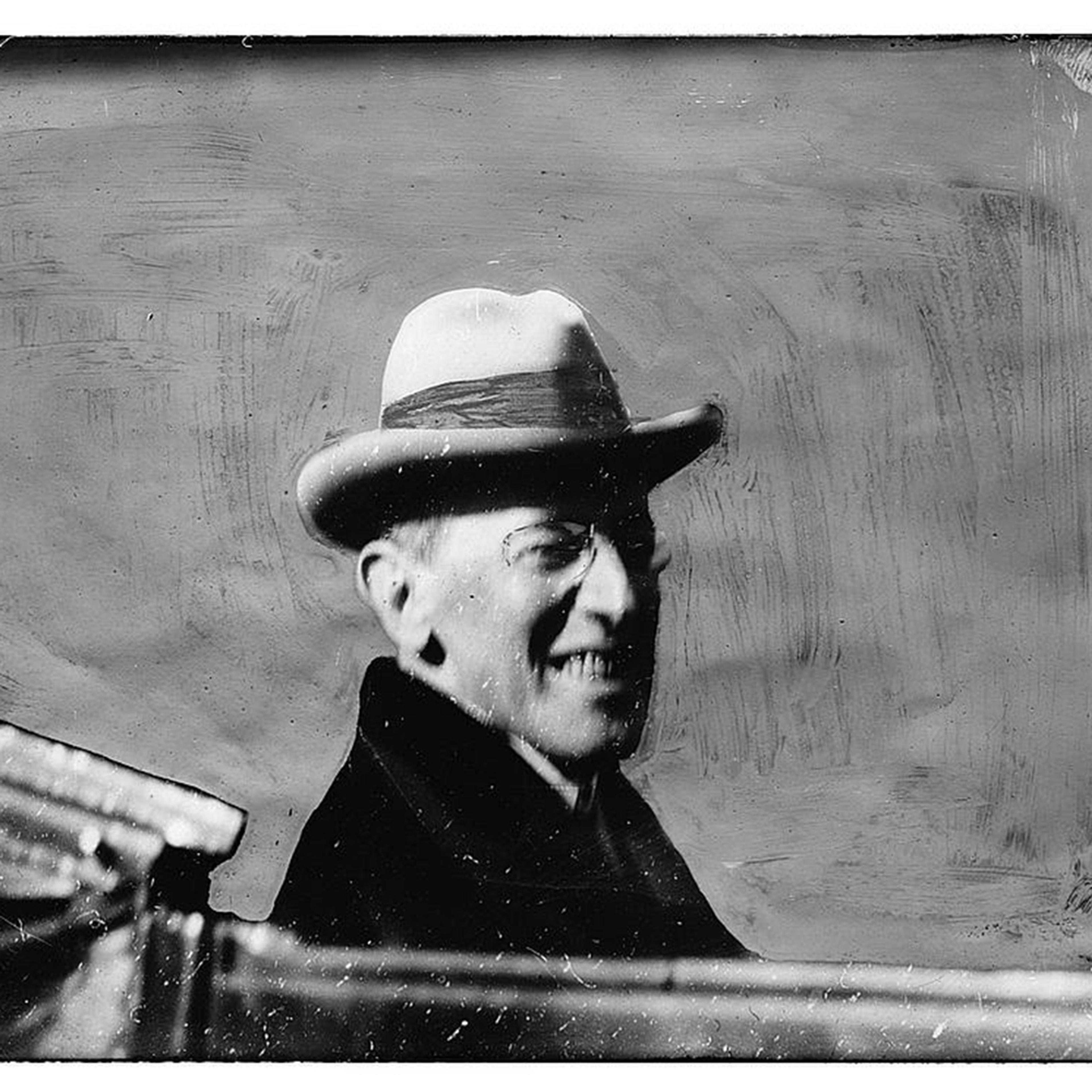

Woodrow Wilson Library of Congress

We all know what Juliet says about a rose: by any other name, it would smell as sweet. But we probably don’t remember why she says this, or what happens next. Juliet is lamenting that a certain young man happens to be called ‘Romeo Montague’, a name associated with her family’s dire enemies. Romeo then emerges from the shadows and insists that the name is ‘hateful to myself, because it is an enemy to thee’. He declares his moniker dispensable, under one condition: ‘Call me but love, and I’ll be new baptised; henceforth I never will be Romeo.’

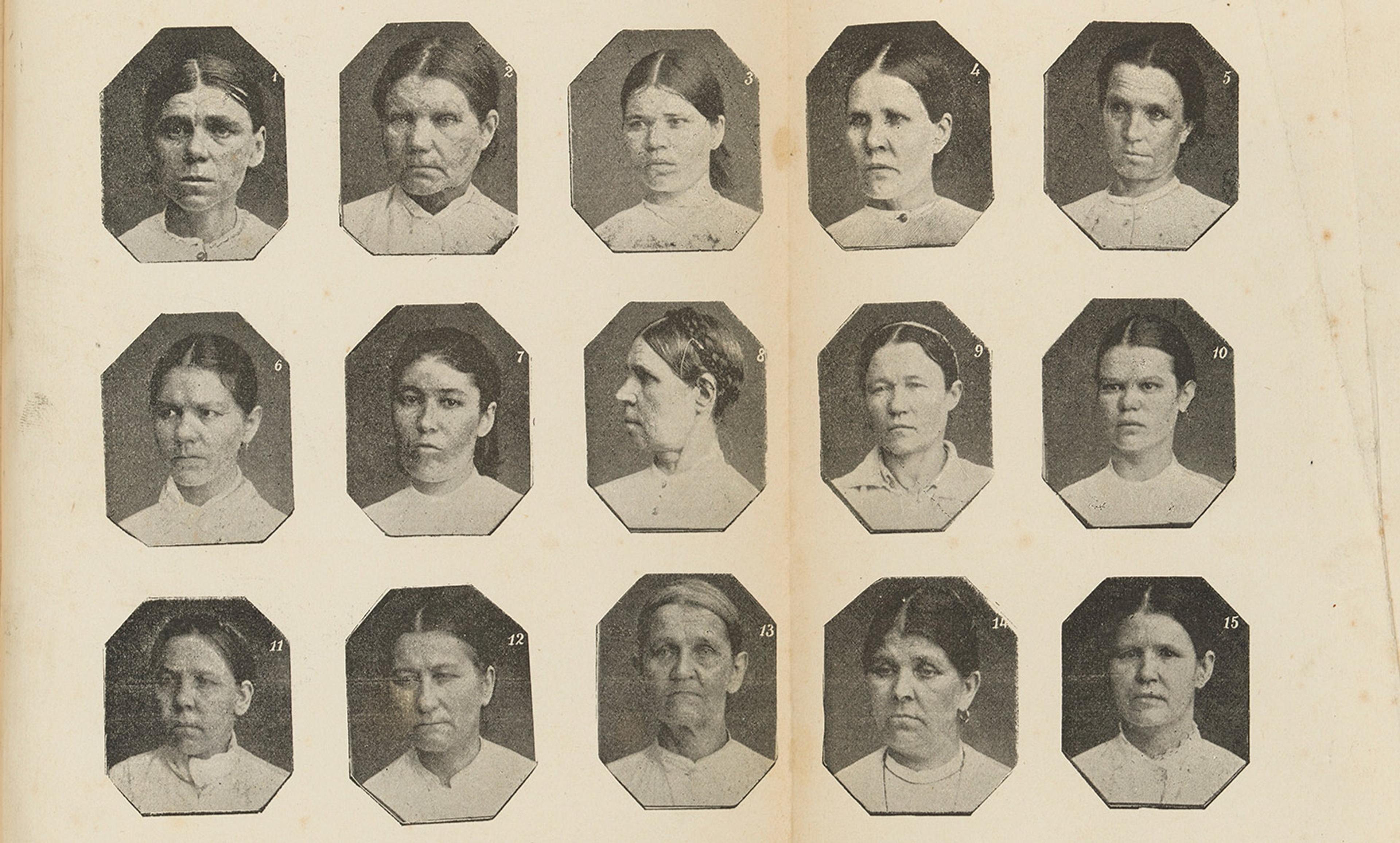

What altered scent might emanate from a renamed Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs? The Princeton institution faces calls to drop its nominal affiliation with America’s 28th president, who was also governor of New Jersey, president of the university, and a horrible racist. Similarly, students at Yale have demanded a rebranding of Calhoun College, named after John Calhoun who championed ‘Indian removal’ and told the Senate that slavery was a ‘positive good’. And Georgetown University, my own alma mater, has agreed to strip the names of two Jesuit slave-sellers from campus buildings. Across the country, student Juliets are asking their administrator Romeos to be newly baptised.

And why not? It is reasonable to prefer not to live in a quadrangle named after a man who extolled the ‘positive good’ of your great-great-grandparents’ forced labour. It is reasonable to wish not to study in a place that honors a man who would have you keep to your own, segregated end of the lecture hall. For students of colour, living in a United States that preaches equality and practises something else, it is reasonable to expect an honest reckoning with our damaged patriarchs.

But the problem is consistency. Once we’ve started rescinding honours from besmirched heroes, where should we stop? On any reasonable scale of evil, the segregationist Wilson cannot be as bad as George Washington, who owned hundreds of slaves. So must we also rename several universities, a northwestern state, and the District of Columbia? The last, in fact, seems to require double renaming, as Christopher Columbus is now seen as a genocidal monster. Perhaps ‘America’ itself ought to go: Amerigo Vespucci wrapped up his first voyage to the New World by setting a native village on fire and ‘thereon made sail for Spain with 222 captive slaves’.

This, say opponents, is the absurdity to which we will be reduced. Where does the bonfire end? Surely we can’t consider renaming every legacy of a moral scofflaw. Who has the time?

But, in fact, we regularly give things new names. In 2005, a man in California petitioned to rename Mount Diablo, because federal rules prohibit naming a geographic formation after ‘a living person’ such as Satan. The man’s preferred alternative, ‘Mount Reagan’, was unsuccessful, but this has not stopped the Mount Reagan Project from questing after another peak to rechristen. Ronald Reagan’s name, incidentally, already adorns National Airport in Virginia – which was previously named for none other than the sacrosanct Washington. It would be worrisome if this reductio of name-changing was deemed absurd only when racism is the issue. Still, it is worth pausing to consider just what it takes to give something a name.

The British philosopher J L Austin gave naming as a prime example of a ‘performative utterance’, the kind of speech act whereby merely saying something makes it so. But not all attempted naming is felicitous. In How to Do Things with Words (1962), Austin offered the following delightful demonstration:

Suppose, for example, I see a vessel on the stocks, walk up and smash the bottle hung at the stern, proclaim: ‘I name this ship the Mr Stalin’ and for good measure kick away the chocks: but the trouble is, I was not the person chosen to name it… We can all agree (1) that the ship was not thereby named; (2) that it is an infernal shame.

Austin’s point was that the giving of a name requires a certain social authority. But unlike the Royal Navy, in schools and cities the authority to name does not entirely belong to a single person. Students (and faculty, staff and alumni) have an interest in not seeing their college linguistically cavort with blackguards. The citizens of a democratic state have a right to call themselves as they wish. And the procedure by which we determine how to (re)name our collective institutions has its own name – it is called debate. Why not have this debate, openly and honestly, rather than dismiss the entire project?

The US philosopher Saul Kripke is known for his causal theory of reference. According to Kripke, proper names pick out their objects via a causal chain going back to the object’s ‘baptism’. Once upon a time, someone (probably his parents) pointed at Romeo and said: ‘That one will be called Romeo,’ and this caused other people to call the child Romeo, onward until the night under Juliet’s balcony. But there is nothing in this story to prevent a re-baptism, or a displacement of the old name by the same causal channels. Suppose the young lovers decide that the man formerly known as Romeo Montague is now Keyser Söze. If they can cause enough fair Veronese to refer to him thus, then so shall he be (though this is unlikely to solve Keyser’s trouble with his in-laws).

We are links in a causal chain of reference, stretching back to institutional baptisms in 1931 and 1948, when university administrators pointed to a college and called it Calhoun, or pointed to a school and called it Wilson. These were performative utterances, issued with full authority, and part of their aim was to honour the legacies of dead racists. We do not have to be unthinking links in the chain. We, collectively, have the authority to pass on these names, or to replace them. Whatever we do – continue the chain or disrupt it – we are making a choice about whether to uphold the honour intended by those baptisms.

In fact, the students at Princeton are not asking us to make a comprehensive judgment: Wilson, good man or bad? The idea is to ask: does continuing to apply the name of such a person express our values, rather than the values of a gone generation? We are not deciding the fate of Wilson’s eternal soul. We are asking whether we, who are the only ones with the authority to keep or change the name, have good reason to pass the name on to the next generation.

We know that renaming tends to follow political revolution. Famously, Byzantium turned to Constantinople, which turned to Istanbul. Saint Petersburg was Leningrad was Petrograd was Saint Petersburg. Decolonisation brought a mass shedding of imposed titles, from Mumbai (Bombay) to Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) to Jakarta (Batavia). We are ready to accept that names change with the times and with the politics. Or would you insist that I am writing in New Amsterdam?

So if renaming can follow political revolution, then why not moral revolution? Why are we not free to ask ourselves whether to uphold the values that led our ancestors to name in honour of slaveholders and segregationists?

Perhaps we will decide, together, that on balance the good done by Washington or Wilson outweighs the evil. Perhaps. But I think we should seriously listen to those whose histories are most in the weighing. It can be hard, for some whose ancestors were not enslaved or segregated, to fully appreciate the pain caused by honouring these names. Yet even if you cannot understand it yourself, you can see it in others. And perhaps this will move you to agree, as an act of civic love, to accede to their requests. Like Romeo, listening in the night, we might find our collective name hateful to ourselves, ‘because it is an enemy to thee’.