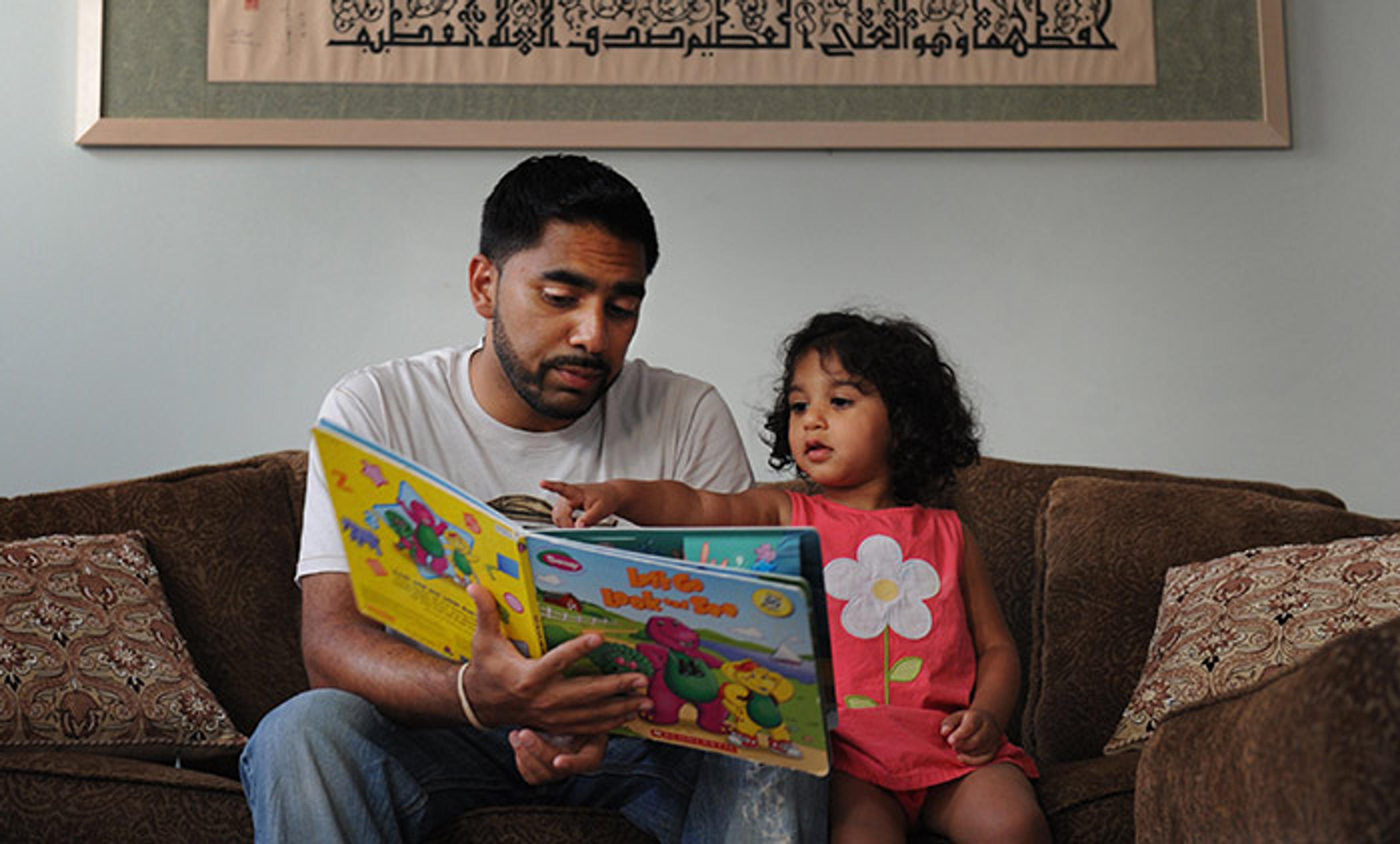

Photo by Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Parents have many reasons for raising their children with multiple languages. Some hope for better career opportunities for their offspring, while others focus on the reported cognitive and intellectual benefits of learning an additional tongue, including better attention skills, improved memory, and a quicker decision-making process. Still others, such as the writer Ben Faccini in Aeon, want to fight against the worldwide dominance of the English language.

Finally, for countless families, multilingualism is simply a way of life, a tradition that they want to bestow on their children. But no matter what the motivation behind the parents’ desire for giving their children a multilingual upbringing, the questions and worries are the same. How can I manage to teach my child all these languages? What is the best method for achieving this goal? And how can I stand firm against the challenges and difficulties that inevitably come with raising a family that differs from ‘the norm’?

First of all, there has been some confusion concerning the terms. Many people use ‘bilingual’ and ‘multilingual’ interchangeably. Traditionally, the first term referred to the knowledge of two languages, while the other meant that someone spoke three or more. Annick De Houwer, a professor of language acquisition and multilingualism at the University of Erfurt in Germany, uses the term ‘bilingual’ to describe a person who knows two or more languages.

Most books and articles aimed at families raising bilingual children claim that the best way to teach a child a language is OPOL, or the one-person, one-language method. According to this approach, one parent speaks one language (often the majority language) while the other speaks the minority language. For many reasons, this method is not ideal. In fact, when De Houwer analysed a huge sample of bilingual children living in the Flemish part of Belgium, she found that only a part ended up speaking both languages. The success rate was especially high when both parents spoke the home language while the children learned the other language at school. Moreover, even if the parents spoke more than two languages, the children acquired only the ones that the parents actively used at home. This makes sense, given that there is a direct correlation between the amount of time spent talking to a child and the success of language acquisition. However, the exact amount of time needed is not known. Some believe that a child needs to hear a language more than 30 per cent of waking hours in order to speak it with ease, but there is no scientific evidence to support this.

In the first half of the 20th century, multilingualism used to be a dirty word, and speaking more than one language was associated with a lower IQ and decreased cognitive skills. While these negative assumptions are wrong, many of them still prevail. Countless families have been asked to stop speaking their mother tongue to their children, out of fear that speaking an additional language or two will not just confuse children, but also hamper integration in children of immigrants. These fears are unfounded, and based on a distrust of differences in skin colour, culture and religious identity, said De Houwer.

The prestige that a language enjoys also plays a role in the success of multilingualism. In Europe, languages such as English, German and French are respected and acknowledged, while eastern European languages such as Russian or Polish, as well as Middle Eastern languages such as Arabic or Turkish, are regarded with suspicion. De Houwer warns that this could lead to children losing the motivation for learning their mother tongues. When their languages are not accepted, she noted, the children don’t feel accepted either. What’s more, language discrimination violates article 30 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Parents can consciously decide to send their children to a school where the language and culture will be respected.

Thanks to the work of researchers such as Ellen Bialystok at York University in Canada, bilingualism has become something of a fashion. In the United States, bilingual and immersion schools, designed specifically to help minorities retain their languages, are currently attracting families from white, middle-class backgrounds who jumped at the opportunity of giving their children the gifts of multilingualism. This goal, while commendable, might actually push out the very target groups that these schools were built to support.

Middle-class families were also more likely to engage in what the sociologist Annette Lareau at the University of Pennsylvania called ‘concerted cultivation’, an approach where parents actively fostered the children’s skills and abilities in order to maximise success. But this group of children were also overscheduled, exhausted and lacked time to play, get bored, and just be children. Now, multilingualism has become a part of the intensive parenting trend.

Some parents today approach raising multilingual children the same way that they approach nutrition, discipline or schooling: a zero-sum game where the only right way to success is through sacrifice and surrender of all parental needs. This is not necessary, and can even be harmful. Research showed that parents, especially mothers, who believed in the tenets of intensive parenting were more likely to be depressed.

Also under attack is the idea that ‘more and earlier is better’. De Houwer said that children learn a foreign language best after the age of 12, noting that the current trend in European countries of teaching children English at an ever-earlier age is not showing the right results. Starting a language too early – especially if a child is already learning a language at home from one of his or her parents – could cause the child to lose all motivation to learn.

The sheer amount of information available to parents of multilingual children can be overwhelming, especially on top of all the other parenting advice mothers and fathers get. As a result, parents can become anxious, nervous and unsure of themselves and their teaching techniques.

While raising multilingual children is hard work, it’s time to relax. Ultimately, the goal is not even that unique. According to estimates, perhaps half the world’s population already speaks two languages or more, and many speak a dialect on top of that.

And the very act of learning languages could be an emotional boon. The biggest benefit, as the linguist Amy Thompson at the University of South Florida found, was that multilingualism makes people more tolerant because it helps them acquire two very important skills – cultural competence (a better understanding of various ways that people behave and communicate), and tolerance of ambiguity (how people approach new situations). It follows, then, that the biggest lesson to learn from bilingualism isn’t really the mechanics: the how, or even the why, of it. It’s much bigger than that. Raising multilingual children is about raising open-minded, tolerant and globally aware citizens. And if that’s the case, parents should overcome challenges and lead the way.