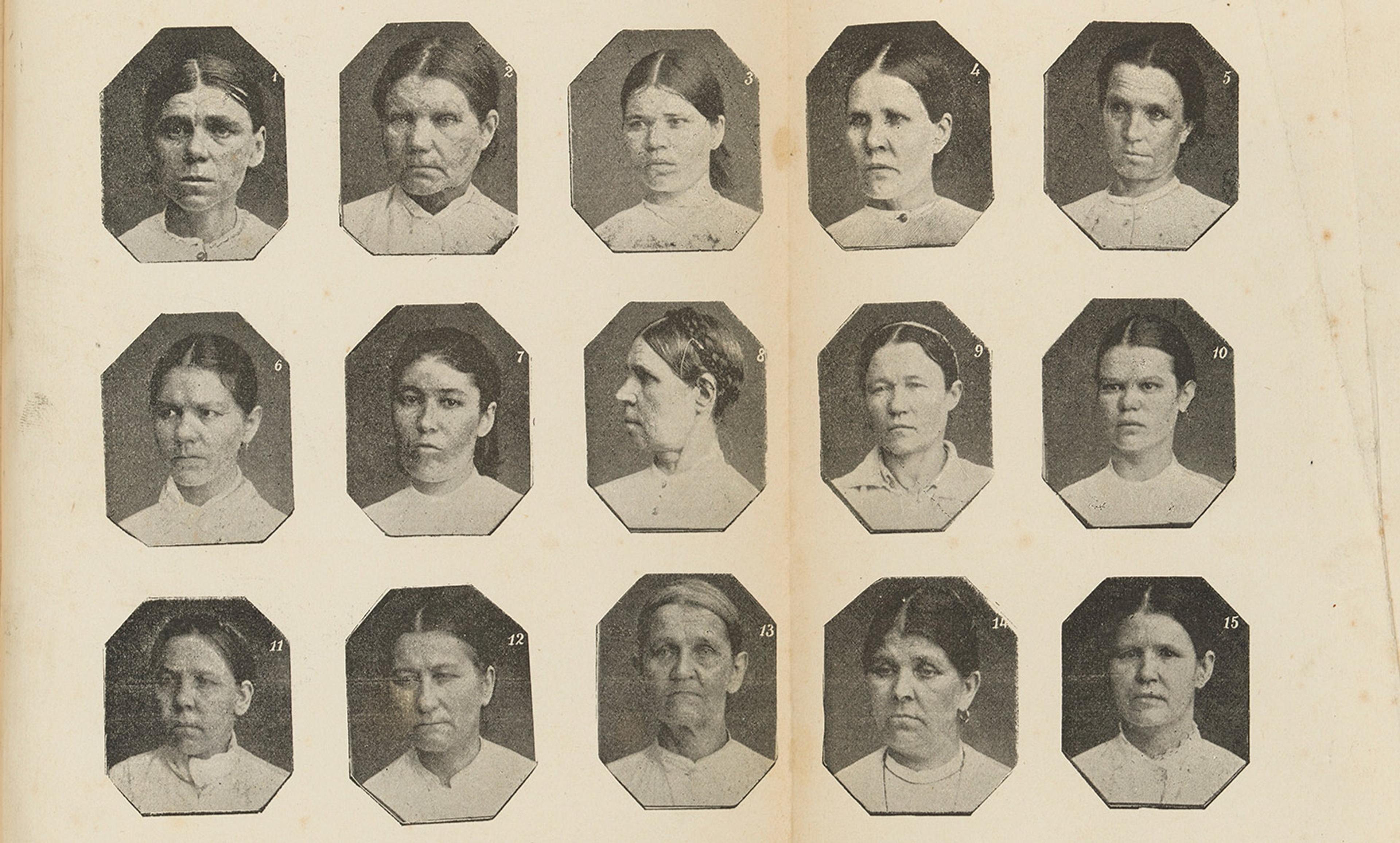

JL Hopgood/Flickr

Imagine a world in which all the babies born each day were randomly redistributed among the biological parents. The infant assigned to any given set of parents could be white, black, Asian, Hispanic, Native American, or any combination thereof (and that’s just the US); the baby could be perfectly healthy or grossly deformed. Parents would know only that their child was not their biological child. Let us call this social mixing.

This plan is of course politically impossible, perhaps even repellent. Our goal, however, is to engage the reader in a thought experiment, to examine why it stirs up such uncomfortable feelings.

Is the idea so frightening? Yes it is. It is a frightening thought that your own biological child, the one sitting there now doing her homework, might have gone to an impoverished mother or a drug addict, perhaps have been beaten, perhaps starved. But why, save for genetic chauvinism, do we view with comparative equanimity the everyday reality of other people’s children subject to the same treatment by their own biological mothers?

You may argue that genetic bias is indelible in human nature. Social mixing would not only disturb the comfort of this fatalistic attitude, but also use genetic chauvinism for ends beyond mere economic equality, providing grounds for a compassion that goes beyond the wellbeing of our immediate families. Since any man might be your biological brother, any woman your biological sister, concern for them would have to be expressed by a concern for a common good.

A second effect of social mixing would be to generate a strong interest in the health and wellbeing of expectant mothers, which would ultimately translate into an interest in the social and biological welfare of everyone. Since any child might end up our own, we would provide the social and educational environments that would best enhance their development. Ghettos and slums would be an eyesore for us all. Poverty, drug, and alcohol addiction are already everyone’s problem, but this fact would be more meaningful than it is now. The child of that addict might be our biological child. Every victim of a drive-by shooting might be a member of our genetic family. Each of us would see the link between our fate and the fate of others.

Third, the superficial connection between colour and culture would be severed. Racism would be wiped out. Racial ghettos would disappear; children of all races would live in all neighbourhoods. Any white child could have black parents and any black child could have white parents. Imagine the US president flanked by his or her black, white, Asian and Hispanic children. Imagine if social mixing had been in effect 100 years ago in Germany, Bosnia, Palestine or the Congo. Racial, religious, and social genocide would not have happened.

Fourth, the plan accords with John Rawls’s concept of justice, introducing a welcome element of randomness into the advantages that each child can expect. At the present time, if you are a child of Bill Gates, you will have not only a genetic advantage but also a material one. Under a regime of social mixing, any baby could find herself the child of Bill Gates and enjoy the opportunity of optimally exercising whatever her genetic gifts might be. As for Bill Gates’s biological child, he might find himself the son of a barber, but with his natural genetic gifts he might make the most of a less than optimal educational environment.

There are, of course, many natural objections to this idea. It will be said that one of the joys of marriage is for lovers to see the product of their love. To this we say that the product of one’s love lies not in the genetic production of a human being but in the mutual cultivation of the life of a child. But isn’t it true that either the genetic match between parent and child or a bond formed between mother and child in the womb makes each parent uniquely fit to raise his or her own child and less fit to raise another child? The evidence for such idiosyncrasy is slight. True, adopted children tend to have more mental and physical problems than non-adopted ones. But children are often adopted at relatively advanced ages, after they have formed close attachments with caregivers. Children adopted during their first year are at no disadvantage relative to non-adopted children.

It will be objected that in defusing genetic chauvinism we will be giving up our only secular moral constraint – which translates into the fear that under social mixing people will be as indifferent to their own real children as they are now to the biological children of others. But there are no grounds for such deep pessimism. Look at the behaviour of adoptive parents now, or look at the practice of surrogate motherhood. The many apparently infertile parents who adopt a baby only to have a biological child subsequently do not tend to reject the first child.

It may be objected that under social mixing cultural diversity would disappear. But this would only be true for diversity that depends on the shape of your features and the colour of your skin. This is the kind of diversity that racists wish to maintain. The cultural diversity we care about – of language, food, dress, religion, music, speech – would be preserved no less than it is now.

It may be objected that parents’ desire to have their own biological children is so strong that they would be blind to the public good, that they would have babies and bring them up in secret. But those babies would not have birth certificates, they would not be citizens, they could not vote, serve in public office and so forth. If discovered, the children might be taken away after the strong bonds of psychological (as opposed to biological) parenthood had been formed. Few Americans would risk these penalties.

It will be objected that incest would occur frequently in a society where biological kinship was obscured. In answer to this, we now have the ability to test prospective parents and to forbid marriages between people with close genetic overlap – whatever the cause. But even if we did not have this ability, is it likely that incest would be more frequent under our plan than it is now (notwithstanding taboos) among close biological relatives living together? Our proposal is certainly no cure-all for all the ills that plague society. People do rape, rob, and murder their relatives and would undoubtedly continue to do so if their relatives were genetically unrelated to them. But our proposal would reduce crimes due to genetic chauvinism – and there are enough of these.

It may be objected that people would not want to bear children only to have them raised by strangers. But genetic narcissism may not be the optimal motive for having children. There may be no correlation between the biological capacity to have children and the ability to cultivate the optimal development of a child. It may be a good thing if only people who passionately wished to be an integral part of the life trajectory of another human being raised children.

Genetic chauvinism lives on very strongly in our culture. Modern fiction and cinema often present adoptees’ searches for biological parents and siblings in a highly positive light. The law in child custody cases is biased towards biological parents over real parents. You might claim that this bias itself is ‘natural’. It is so common as to seem part of our biological makeup. But subjugation of women was also common in primitive human cultures and remains so in many cultures today. Unnatural as it sounds, social mixing promises many advantages. If we are not willing to adopt it, we should consider carefully why. And if naturalness is the key, we should ask ourselves why on this matter, ungoverned nature should trump social cohesion.