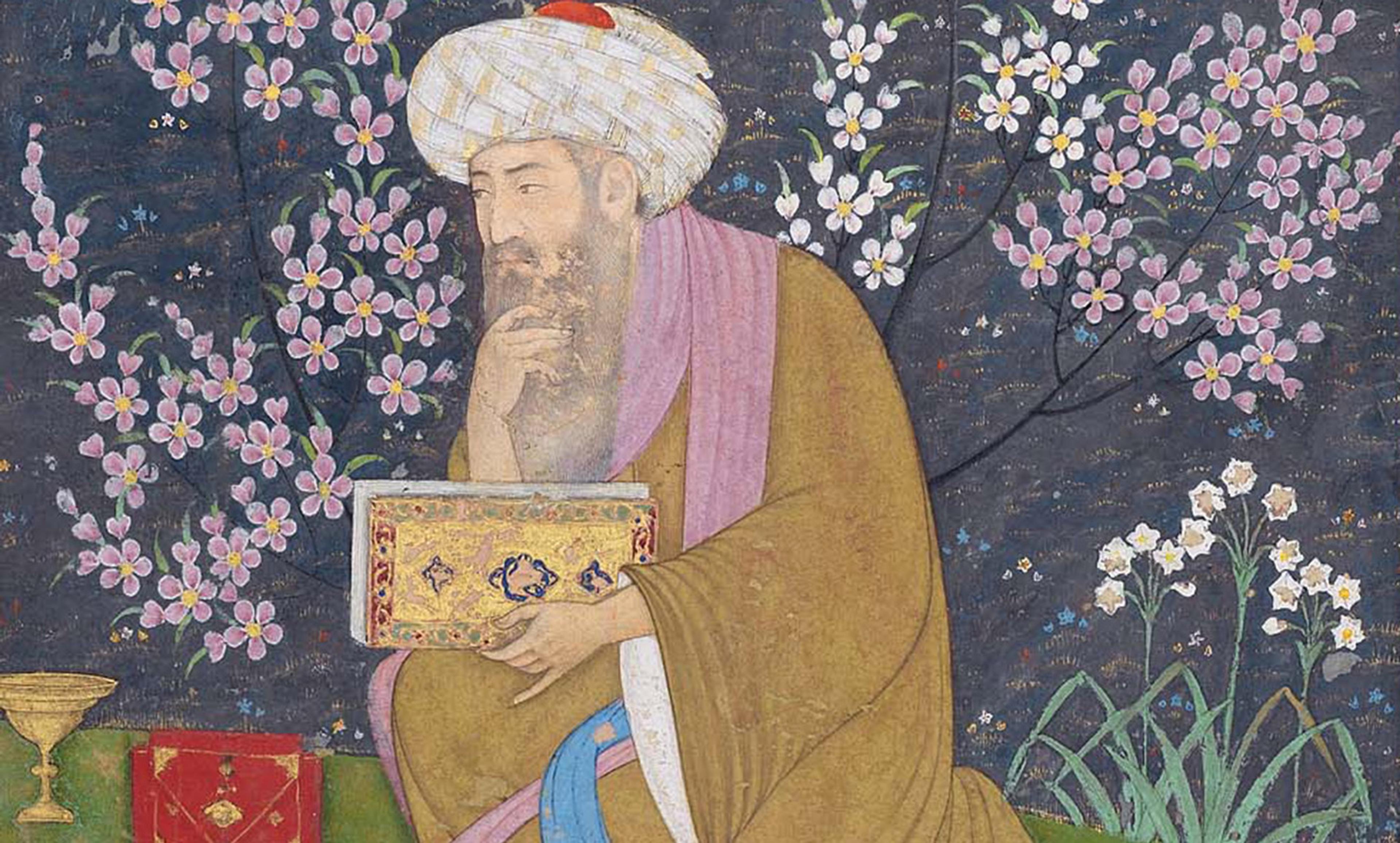

Album folio fragment with scholar in a garden. Attributed to Muhammad Ali 1610-15. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ibn Tufayl, a 12th-century Andalusian, fashioned the feral child in philosophy. His story Hayy ibn Yaqzan is the tale of a child raised by a doe on an unnamed Indian Ocean island. Hayy ibn Yaqzan (literally ‘Living Son of Awakeness’) reaches a state of perfect, ecstatic understanding of the world. A meditation on the possibilities (and pitfalls) of the quest for the good life, Hayy offers not one, but two ‘utopias’: a eutopia (εὖ ‘good’, τόπος ‘place’) of the mind in perfect isolation, and an ethical community under the rule of law. Each has a version of human happiness. Ibn Tufayl pits them against each other, but each unfolds ‘no where’ (οὐ ‘not’, τόπος ‘place’) in the world.

Ibn Tufayl begins with a vision of humanity isolated from society and politics. (Modern European political theorists who employed this literary device called it ‘the state of nature’.) He introduces Hayy by speculating about his origin. Whether Hayy was placed in a basket by his mother to sail through the waters of life (like Moses) or born by spontaneous generation on the island is irrelevant, Ibn Tufayl says. His divine station remains the same, as does much of his life, spent in the company only of animals. Later philosophers held that society elevates humanity from its natural animal state to an advanced, civilised one. Ibn Tufayl took a different view. He maintained that humans can be perfected only outside society, through a progress of the soul, not the species.

In contrast to Thomas Hobbes’s view that ‘man is a wolf to man’, Hayy’s island has no wolves. It proves easy enough for him to fend off other creatures by waving sticks at them or donning terrifying costumes of hides and feathers. For Hobbes, the fear of violent death is the origin of the social contract and the apologia for the state; but Hayy’s first encounter with fear of death is when his doe-mother dies. Desperate to revive her, Hayy dissects her heart only to find one of its chambers is empty. The coroner-turned-theologian concludes that what he loved in his mother no longer resides in her body. Death therefore was the first lesson of metaphysics, not politics.

Hayy then observes the island’s plants and animals. He meditates upon the idea of an elemental, ‘vital spirit’ upon discovering fire. Pondering the plurality of matter leads him to conclude that it must originate from a singular, non-corporeal source or First Cause. He notes the perfect motion of the celestial spheres and begins a series of ascetic exercises (such as spinning until dizzy) to emulate this hidden, universal order. By the age of 50, he retreats from the physical world, meditating in his cave until, finally, he attains a state of ecstatic illumination. Reason, for Ibn Tufayl, is thus no absolute guide to Truth.

The difference between Hayy’s ecstatic journeys of the mind and later rationalist political thought is the role of reason. Yet many later modern European commentaries or translations of Hayy confuse this by framing the allegory in terms of reason. In 1671, Edward Pococke entitled his Latin translation The Self-Taught Philosopher: In Which It Is Demonstrated How Human Reason Can Ascend from Contemplation of the Inferior to Knowledge of the Superior. In 1708, Simon Ockley’s English translation was The Improvement of Human Reason, and it too emphasised reason’s capacity to attain ‘knowledge of God’. For Ibn Tufayl, however, true knowledge of God and the world – as a eutopia for the ‘mind’ (or soul) – could come only through perfect contemplative intuition, not absolute rational thought.

This is Ibn Tufayl’s first utopia: an uninhabited island where a feral philosopher retreats to a cave to reach ecstasy through contemplation and withdrawal from the world. Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zarathustra would be impressed: ‘Flee, my friend, into your solitude!’

The rest of the allegory introduces the problem of communal life and a second utopia. After Hayy achieves his perfect condition, an ascetic is shipwrecked on his island. Hayy is surprised to discover another being who so resembles him. Curiosity leads him to befriend the wanderer, Absal. Absal teaches Hayy language, and describes the mores of his own island’s law-abiding people. The two men determine that the islanders’ religion is a lesser version of the Truth that Hayy discovered, shrouded in symbols and parables. Hayy is driven by compassion to teach them the Truth. They travel to Absal’s home.

The encounter is disastrous. Absal’s islanders feel compelled by their ethical principles of hospitality towards foreigners, friendship with Absal, and association with all people to welcome Hayy. But soon Hayy’s constant attempts to preach irritate them. Hayy realises that they are incapable of understanding. They are driven by satisfactions of the body, not the mind. There can be no perfect society because not everyone can achieve a state of perfection in their soul. Illumination is possible only for the select, in accordance with a sacred order, or a hieros archein. (This hierarchy of being and knowing is a fundamental message of neo-Platonism.) Hayy concludes that persuading people away from their ‘natural’ stations would only corrupt them further. The laws that the ‘masses’ venerate, be they revealed or reasoned, he decides, are their only chance to achieve a good life.

The islanders’ ideals – lawfulness, hospitality, friendship, association – might seem reasonable, but these too exist ‘no where’ in the world. Hence their dilemma: either they adhere to these and endure Hayy’s criticisms, or violate them by shunning him. This is a radical critique of the law and its ethical principles: they are normatively necessary for social life yet inherently contradictory and impossible. It’s a sly reproach of political life, one whose bite endures. Like the islanders, we follow principles that can undermine themselves. To be hospitable, we must be open to the stranger who violates hospitality. To be democratic, we must include those who are antidemocratic. To be worldly, our encounters with other people must be opportunities to learn from them, not just about them.

In the end, Hayy returns to his island with Absal, where they enjoy a life of ecstatic contemplation unto death. They abandon the search for a perfect society of laws. Their eutopia is the quest of the mind left unto itself, beyond the imperfections of language, law and ethics – perhaps beyond even life itself.

The islanders offer a less obvious lesson: our ideals and principles undermine themselves, but this is itself necessary for political life. For an island of pure ethics and law is an impossible utopia. Perhaps, like Ibn Tufayl, all we can say on the search for happiness is (quoting Al-Ghazali):

It was – what it was is harder to say.

Think the best, but don’t make me describe it away.

After all, we don’t know what happened to Hayy and Absal after their deaths – or to the islanders after they left.