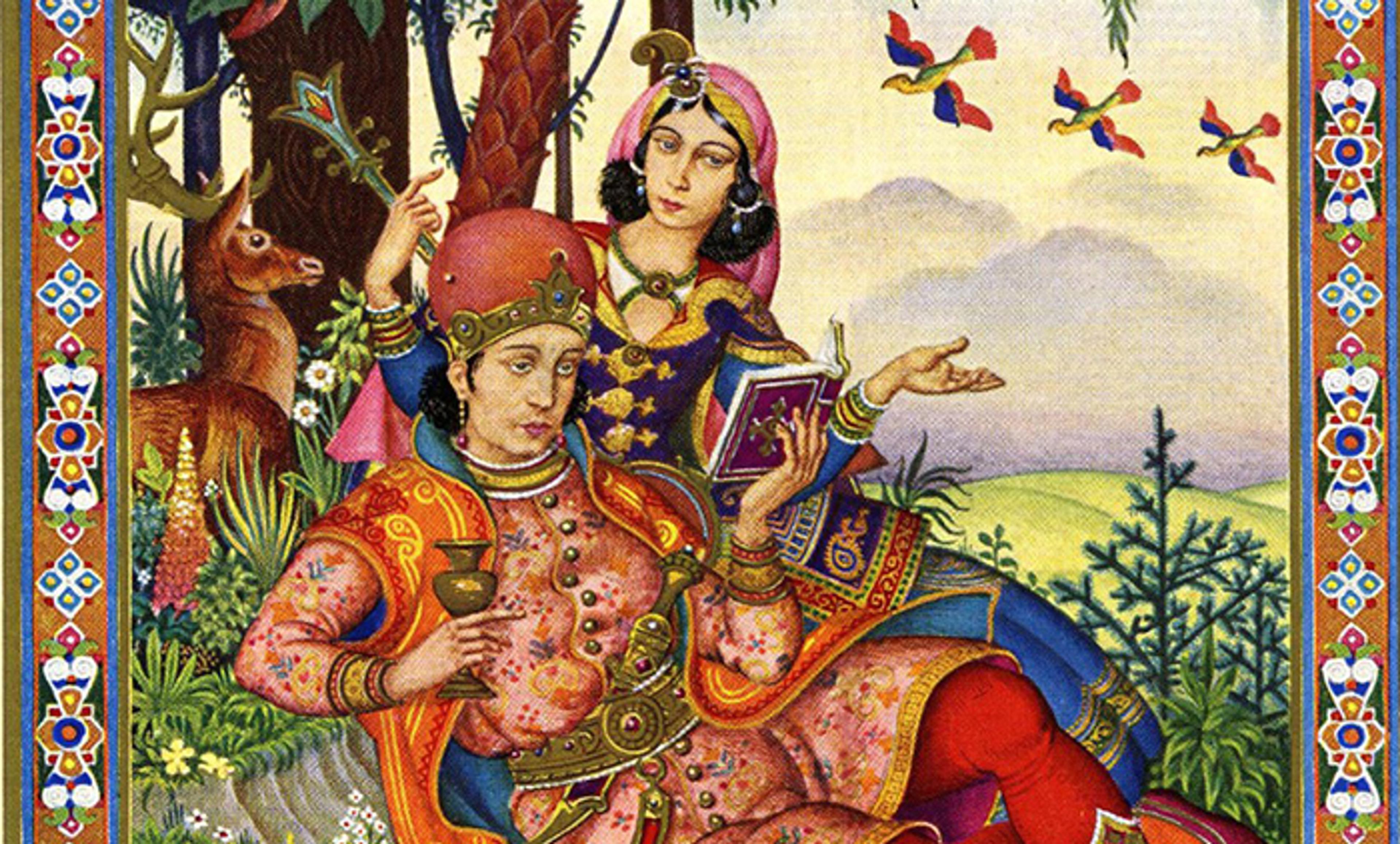

From The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1940) illustrated by Arthur Szyk. Courtesy Wikipedia

How did a 400-line poem based on the writings of a Persian sage and advocating seize-the-day hedonism achieve widespread popularity in Victorian England? The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám was written by the eccentric English scholar Edward FitzGerald, drawing on his loose translation of quatrains by the 12th-century poet and mathematician Omar Khayyám. Obscure beginnings perhaps, but the poem’s remarkable publishing history is the stuff of legend. Its initial publication in 1859 – the same year as Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and J S Mill’s On Liberty – went completely unnoticed: it didn’t sell a single copy in its first two years. That all changed when a remaindered copy of FitzGerald’s 20-page booklet was picked up for a penny by the Celtic scholar Whitley Stokes, who passed it on to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who subsequently fell in love with it and sang its praises to his Pre-Raphaelite circle.

When, in 1863, it fell into the hands of John Ruskin, he declared: ‘I never did – till this day – read anything so glorious.’ From that moment, there began a cult of Khayyám that lasted at least until the First World War, by which time there were 447 editions of FitzGerald’s translation in circulation. Omar dining clubs sprang up, and you could even buy Omar tooth powder and illustrated playing cards. During the war, dead soldiers were found in the trenches with battered copies tucked away in their pockets.

What then was the extraordinary attraction of the Rubáiyát? The answer sings out from some of its most famous verses:

XXIV

Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend,

Before we too into the Dust descend;

Dust into Dust, and under Dust to lie

Sans Wine, sans Song, sans Singer, and – sans End!

XXXV

Then to the lip of this poor earthen Urn

I lean’d, the Secret of my Life to learn:

And Lip to Lip it murmur’d – ‘While you live

Drink! – for, once dead, you never shall return.’

LXIII

Oh, threats of Hell and Hopes of Paradise!

One thing at least is certain – This Life flies;

One thing is certain and the rest is Lies;

The Flower that once has blown for ever dies.

The Rubáiyát was an unapologetic expression of hedonism, bringing to mind sensuous embraces in jasmine-filled gardens on balmy Arabian nights, accompanied by cups of cool, intoxicating wine. It was a passionate outcry against the unofficial Victorian ideologies of moderation, primness and self-control.

Yet the poem’s message was even more radical than this, for the Rubáiyát was a rejection not just of Christian morality, but of religion itself. There is no afterlife, Khayyám implied, and since human existence is transient – and death will come much faster than we imagine – it’s best to savour life’s exquisite moments while we can. This didn’t mean throwing oneself into wild hedonistic excess, but rather cultivating a sense of presence, and appreciating and enjoying the here and now in the limited time we have on Earth.

This heady union of bodily pleasures, religious doubt and impending mortality captured the imagination of its Victorian audience, who had been raised singing pious hymns at church on a Sunday morning. No wonder the writer G K Chesterton admonishingly declared that the Rubáiyát was the bible of the ‘carpe diem religion’.

The influence of the poem on Victorian culture was especially visible in the works of Oscar Wilde, who described it as a ‘masterpiece of art’ and one of his greatest literary loves. He took up its themes in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). The character of Lord Henry Wotton is a champion of hedonism who explicitly refers to the sensual allures of ‘wise Omar’, and tempts the beautiful young man Dorian to sell his soul for the decadent pleasures of eternal youth. ‘Time is jealous of you, and wars against your lilies and your roses,’ says Lord Henry. ‘A new Hedonism – that is what our century wants.’

Wilde’s novel was a thinly veiled celebration of homosexuality – a crime for which he was gaoled in 1895 (passages of the book were read out at his trial as part of the incriminating evidence). He saw in the Rubáiyát an argument for individual freedom and sexual liberation from the constraints of Victorian social convention, not least because FitzGerald too was well-known for his homosexuality. For Wilde, as for FitzGerald, carpe diem hedonism was far more than the pursuit of sensory pleasures: it was a subversive political act with the power to reshape the cultural landscape.

Hedonism has a bad reputation today, being associated with ‘YOLO’ binge-drinking, drug overdoses, and a bucket-list approach to life that values fleeting novelty and thrill-seeking above all else. Yet the history of the Rubáiyát is a reminder that we might try to rediscover the hidden virtues of hedonism.

On the one hand, it could serve as an antidote to a growing puritanical streak in modern happiness thinking, which threatens to turn us into self-controlled moderation addicts who rarely express a passionate lust for life. Pick up a book from the self-help shelves and it is unlikely to advise dealing with your problems by smoking a joint under the stars or downing a few tequila slammers in an all-night club. Yet such hedonistic pursuits – enjoyed sensibly – have been central to human culture and wellbeing for centuries: when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas, they discovered the Aztecs tripping on magic mushrooms.

On the other hand, the kind of hedonism popularised by the Rubáiyát can help to put us back in touch with the virtues of direct experience in our age of mediation, where so much of daily life is filtered through the two-dimensional electronic flickers on a smartphone or tablet. We are becoming observers of life rather than participants, immersed in a society of the digital spectacle. We could learn a thing or two from the Victorians: let us keep a copy of the Rubáiyát in our pockets, alongside the iPhone, and remember the words of wise Khayyám: ‘While you live Drink! – for, once dead, you never shall return.’