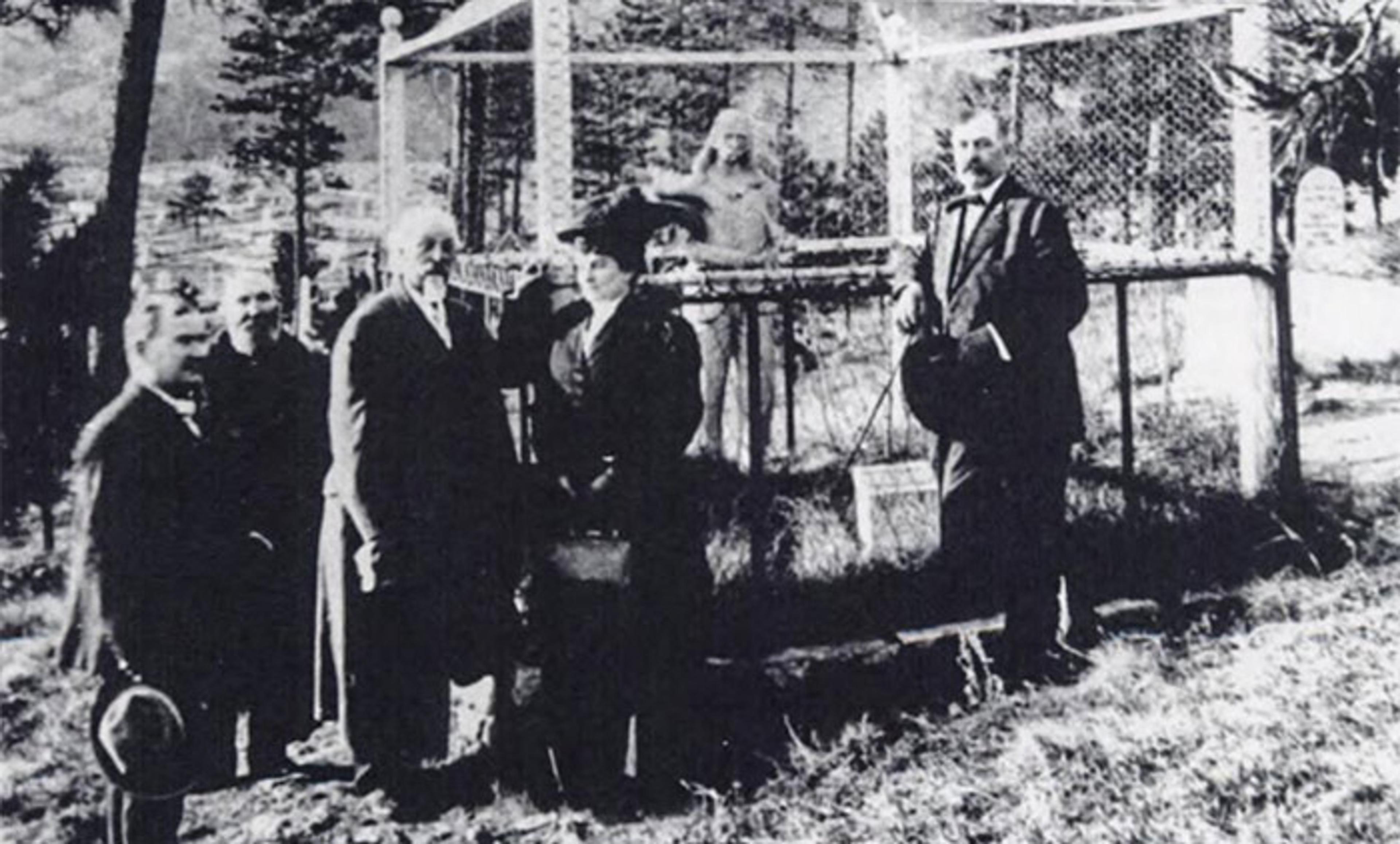

William ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (third from left) alongside the author’s great-great uncle Sheriff Plunkett (right) at Deadwood in 1906. From Deadwood: 1876-1976 (2005) by Beverly Pechan and Bill Groethe/Arcadia Publishing

My great-great-uncle, Matt Plunkett, was the sheriff of Deadwood, South Dakota, back in 1906, when Buffalo Bill Cody came to town. One picture shows moustachioed Sheriff Plunkett with Buffalo Bill next to a statue of Wild Bill Hickok, who’d been killed decades earlier over a poker dispute in a local saloon. According to the caption, Buffalo Bill was in Deadwood to ‘pay his respects’ to a friend and fellow gunslinger, though why my uncle was there I don’t know. Perhaps to keep the peace.

Friendship is the most lawless of our close relationships. That’s why it’s been the dominant human relationship on which today’s digital world, a 21st-century Wild West, has been won. Digital social networks are built on the sharing of private information – just like real-world friendships. The technology encourages us to share, both about ourselves and the people around us. Who is likely to comprise the largest category of people we interact with every day? Friends, from the silver to the gold, as the old song goes, and many other types of metal too.

Friends are tied to each other through emotions, customs and norms – not through a legally defined relationship, such as marriage or parenting, that imposes obligations. Anybody can become friends, we believe, and more is always merrier. But with the advent of the digital domain, friendship has become more fraught. Online and off, we can share information about our friends without their permission and without legal restriction (except for slander and libel).

Information shared between friends can wind up being seen by people outside the friendship network who are not the intended audience. One example is the Harvard Facebook group scandal a few years ago when racist, offensive content allegedly meant as inside jokes between admitted students was treated as grounds for revoking these students’ offers of admission to Harvard University.

Sometimes we share a friend’s information unwittingly. For instance, in-person confidences can inadvertently find their way to the public domain; all it takes is one careless email or the wrong privacy setting on a Facebook post. As we – and eventually our children – apply for jobs, prospective employers will likely use social media or other available digital data trails to learn about us and judge us. Therefore, what our friends reveal about us matters a great deal.

Our online friendships can even get us in legal trouble. Digital social networks are already used to detain people trying to cross into the United States when statements by friends in their network are deemed by border agents to be suspicious or threatening. Adding to the challenge, digital life and the oversharing it entails has, in recent years, given rise to a roving army of monitors and spies. Hired by tech companies to prey on the lawlessness that friendship allows, a sort of friendship KGB imposes systemic surveillance and top-down control of our online lives.

Everyone knows that Facebook uses our information to control its interactions with us, including what shows up in our newsfeed from our friends. Fewer recognise the third-party companies typically behind the scenes of our interactions, often using our information in unknown and uncontrollable ways in pursuit of their own goals, such as when data about Facebook users’ friends made its way to the Cambridge Analytica political consulting firm (without those users’ knowledge or permission) and was then used to micro-target political ads.

Amid all this chaos, friendship itself remains unregulated. You don’t need a licence to become someone’s friend, like you do to get married. You don’t assume legal obligations when you become someone’s friend, like you do when you have a child. You don’t enter into any sort of contract, written or implied, like you do when you buy something.

As teenagers or adults, friends can wind up in regulated areas – roommates, business partners, co-parents, lovers. But from the legal perspective, friendship itself has historically been largely undefined. Notably, there are roughly 210 published opinions by the US Supreme Court (since 1790) that contain the word ‘friendship’. By contrast, more than 1,000 contain the term ‘marriage’. Most of the ‘friendship’ cases don’t even discuss the personal, quotidian experience of being friends. They are about international treaties, or boats whose name includes the word ‘friendship’, or situations when friendship impermissibly shapes the execution of someone’s legal duties, or other situations far removed from whom you play with at recess or text on a bad day.

But finally, we’re seeing a legal definition of friendship start to take shape. Because of the lawless nature of friendship and the lightly regulated space of social media, many jurisdictions have found it necessary to pass laws that address cyberbullying. On their face, these laws don’t set out what you need to do to be a friend; they set out what you are not allowed to do because it makes you a bully. However, if you imagine the opposite of bullying, you can see what the law thinks it means to be a friend.

Let’s take New Hampshire, where I used to be a legal aid lawyer representing youth clients and am now a law professor. The state’s Pupil Safety and Violence Prevention Act (2000) for students in primary and secondary school says that bullying happens when a student does one or more of the following to a peer:

- Physically harms a pupil or damages the pupil’s property;

- Causes emotional distress to a pupil;

- Interferes with a pupil’s educational opportunities;

- Creates a hostile educational environment; or

- Substantially disrupts the orderly operation of the school.

Cyberbullying occurs when this behaviour takes place through the use of electronic devices.

Let’s flip it. To be a friend, a student would need to:

- Physically support or improve a peer or their property;

- Cause emotional comfort to a peer;

- Support or enhance a peer’s educational opportunities;

- Create a positive educational environment; or

- Substantially protect the orderly operation of the school.

To engage in cyberfriendship, this behaviour would need to take place electronically.

The law in New Hampshire doesn’t purport to turn students into friends, but implicit in bullying prevention is friendship promotion. And friendship promotion is already underway in schools through the use of educational technologies that promote social and emotional learning and curricula that award points for prosocial behaviours.

Friendship promotion is a positive goal in theory but it shouldn’t be dictatorial. If you could be punished for not being a friend rather than for being a bully, that would undermine the lawlessness that makes friendship so generative.

We still take the lawlessness of friendship for granted. Going to the town hall to get a ‘licence to friend’? Preposterous! Having to pay support to an ex-friend after the friendship ends? Ridiculous! But the instances of friendship policing we do see have powerful implications for individual friendships and also for the institution of friendship itself. Even if you are sympathetic to the use of friendship policing in a particular situation – for example, if you think that racist statements justify revoking university admission – it is worth reflecting separately on the structure and desirability of friendship policing itself.

We continually strive to protect our freedoms, but the lawless nature of friendship must be protected, too. As friendship becomes less lawless, more guarded by cybersurveillance and the uncle Matts of the world, it might also become less about loyalty, affinity and trust, and more about strategy, currency and a prisoner’s dilemma of sorts (‘I won’t reveal what I know about you if you don’t reveal it about me’). Let’s keep paying our respects to those bonds of friendship that are lawless at heart, opening new frontiers within ourselves.