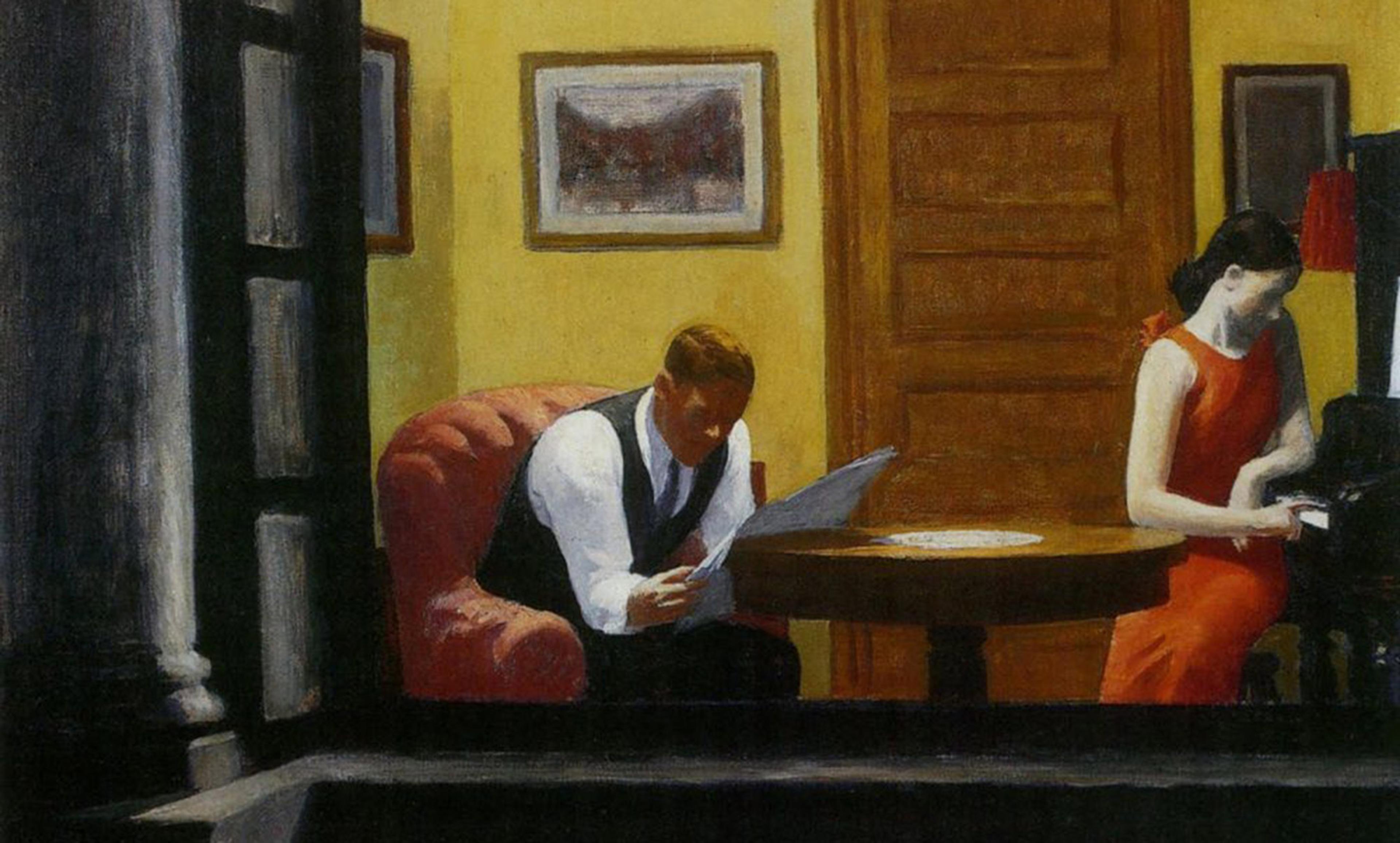

Courtesy Wikimedia

One thing is certain about clichés: you wouldn’t be caught dead using them. They are widely scorned as signs of debased thought, a lack of imagination and the absence of creativity. Thankfully, if you reflect for just a moment on something you’re about to say or write, you can usually avoid falling into the trap. Or can you?

By ‘cliché’, I mean an overused and trite means of expression, ranging from tired sayings to worn-out narratives – things that are much more common in our writing and speech than we assume, or are willing to admit. While we tend to condemn clichés harshly, the scholar of rhetoric Ruth Amossy at Tel Aviv University has shown that they’re in fact crucial to the way we bond with and read other human beings. ‘How have you been?’ – ‘Not bad at all!’: in our daily interactions, clichés represent a communicative common ground, by avoiding the need to question or establish the premises of speech. They are a kind of a shared mental algorithm that facilitates efficient interaction and reaffirms social relationships.

So when did the cliché become such a sin of human communication, a mark of simple minds and mediocre artists? Awareness of the shortcomings of conventionality is certainly not new. Since antiquity, critics have pointed out the weakness of trite language patterns, and used them as fodder for biting parodies. Socrates, for example, was an expert in mocking and unmasking empty, automatic conventions. In Plato’s dialogue Menexenus, he gives a long, mock funeral oration, parodying memorial clichés that overpraise the dead and provide justifications for their loss. Much later, Miguel de Cervantes’s character Don Quixote is captive within the heroic clichés of medieval chivalric-romances, which cause him to fight imagined enemies (thus creating the still-in-use ‘tilting at windmills’ cliché). William Shakespeare in Sonnet 130 wittily rejected the use of clichéd similes to praise one’s beloved (eyes like the Sun, cheeks as roses), stressing the banality and inauthenticity of such ‘false compare’.

However, these criticisms of conventionality are grounded in a certain pre-modern consciousness, where convention and form are the foundation of artistic creation. The link between creativity and total originality was formed later in the 18th century, leading to stronger attacks on trite language. In fact, the word ‘cliché’ – drawn from French – is relatively recent. It emerged in the late-19th century as an onomatopoeic word that mimicked the ‘click’ sound of melting lead on a printer’s plate. The word was first used as the name of the printing plate itself, and later borrowed as a metaphor to describe a readymade, template-like means of expression.

It’s no coincidence that the term ‘cliché’ was created via a connection with modern print technology. The industrial revolution and its attendant focus on speed and standardisation emerged in parallel with mass media and society, as more and more people became capable of expressing themselves in the public sphere. This stoked fears of the industrialisation of language and thought. (Note that ‘stereotype’ is another term derived from the world of print, referring to a printing plate or a pattern.) It seems to be a distinct feature of modernity, then, that conventionality becomes the enemy of intelligence.

In literature and art, clichés are frequently employed to evoke generic expectations. They allow readers to readily identify and orient themselves in a situation, and thus create the possibility for ironic or critical effects. The French novelist Gustave Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas (1911-13), for example, consists of hundreds of entries that aspire to a typical voice uncritically following 19th-century social trends (‘ACADEMY, FRENCH – Run it down but try to belong to it if you can’), popular wisdoms (‘ALCOHOLISM – Cause of all modern diseases’), and shallow public opinions (‘COLONIES – Show sadness when speaking of them’). In this way, Flaubert attacks the mental and social degeneration of cliché-usage, and implies that readymade thought portends destructive political consequences. However, while he goes on the attack against cliché, the substance of the text performs the powerful possibilities of their strategic deployment.

The French theorist Roland Barthes, a follower of Flaubert, was also preoccupied with the political effect of clichés. In ‘African Grammar’, an essay from his book Mythologies (1957), Barthes unmasks popular descriptions of French colonies in Africa (people under colonial rule are always vaguely described as ‘population’; colonisers as acting on a ‘mission’ dictated by ‘destiny’) to show how they function as a disguise for the reality of political cruelty. In ‘The Great Family of Man’, from the same book, he shows that the cliché ‘we are all one big happy family’ disguises cultural injustices with empty universalist language and imagery.

The English writer George Orwell continued this trend of inveighing against the cliché. In his essay ‘Politics and the English Language’ (1946), he condemns journalistic clichés as dangerous constructs that mask political reality with empty language. He denounces dying metaphors (‘stand shoulder to shoulder with’, ‘play into the hands of’), empty operators (‘exhibit a tendency to’, ‘deserving of serious consideration’), bombastic adjectives (‘epic’, ‘historic’, ‘unforgettable’), and various meaningless words (‘romantic’, ‘values’, ‘human’, ‘natural’).

These attacks on clichés are at once captivating and convincing. However, they share two major blind spots. First, they assume that clichés are always used by others, never by the writer herself. This ignores the fact that clichés are intrinsic to communication, almost unavoidable, and subject to contextual interpretation. A seemingly authentic and effective saying is interpreted as a cliché from a different perspective, and vice versa. Thus, the US president Barack Obama declared in the 2013 Democratic National Committee that it’s a cliché to say that America is the greatest country on Earth – but was also accused of constantly using clichés in his own speeches, such the need to ‘protect future generations’, ‘together we can make a difference’ and ‘let me be clear’.

Cliché-denunciation misses another, no less central issue: using them doesn’t necessarily mean that we are blind-copy machines, unaware of the repetitive nature of language and its erosion. We often use clichés deliberately, consciously and rationally to achieve certain goals. Think, for example, of the common statement ‘it is a cliché, but…’; or of the use of clichés ironically. Clichés are always deployed in context, and the context often grants seemingly powerless commonplaces a significant performative force. The nature of cliché is more complex and multilayered than we might think, notwithstanding its terrible reputation.

Perhaps we can begin to think differently about the cliché if we consider a newer and related idea: the ‘meme’, coined by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene (1976). Here, memes are defined as readymade cultural artefacts that duplicate themselves through discourse. Just as the thinking around clichés flourished following the technological revolution of industrialisation, the thinking around memes has peaked in line with the digital revolution. However, while the proliferation of a meme signifies its success, it seems that the more people use a cliché, the less effective it is thought to be. Yet a single cliché, like a popular meme, is not identical across its different manifestations. A meme can appear in a multitude of forms and, even if it’s only shared with no commentary, sometimes the very act of sharing creates an individual stance. Clichés behave the same way. They are granted new meanings in specific contexts, and this makes them effective in various types of interaction.

So, before you pull out the next ‘It’s a cliché!’ allegation, think about some of the clichés you commonly use. Are they typical of your close social and cultural environment? Do they capture common greetings, political sayings or other opinions? Have you spotted some in this essay? Doubtless, you have. It seems, after all, that we can’t live with them, and we can’t live without them.