Thirteen days before the start of the Second World War, a 35-year-old unmarried immigrant woman gave birth slightly prematurely to identical twins at the Memorial Hospital in Piqua, Ohio and immediately put them up for adoption. The boys spent their first month together in a children’s home before Ernest and Sarah Springer adopted one – and would have adopted both had they not been told, incorrectly, that the other twin had died. Two weeks later, Jess and Lucille Lewis adopted the other baby and, when they signed the papers at the local courthouse, calling their boy James, the clerk remarked: ‘That’s what [the Springers] named their son.’ Until then they hadn’t known he was a twin.

The boys grew up 40 miles apart in middle-class Ohioan families. Although James Lewis was six when he learnt he’d been adopted, it was only in his late 30s that he began searching for his birth family at the Ohio courthouse. In 1979, the adoption agency wrote to James Springer, who was astonished by the news, because as a teenager he’d been told his twin had died at birth. He phoned Lewis and four days later they met – a nervous handshake and then beaming smiles. Reports on their case prompted a Minneapolis-based psychologist, Thomas Bouchard, to contact them, and a series of interviews and tests began. The Jim Twins, as they were known, became Bouchard’s star turn.

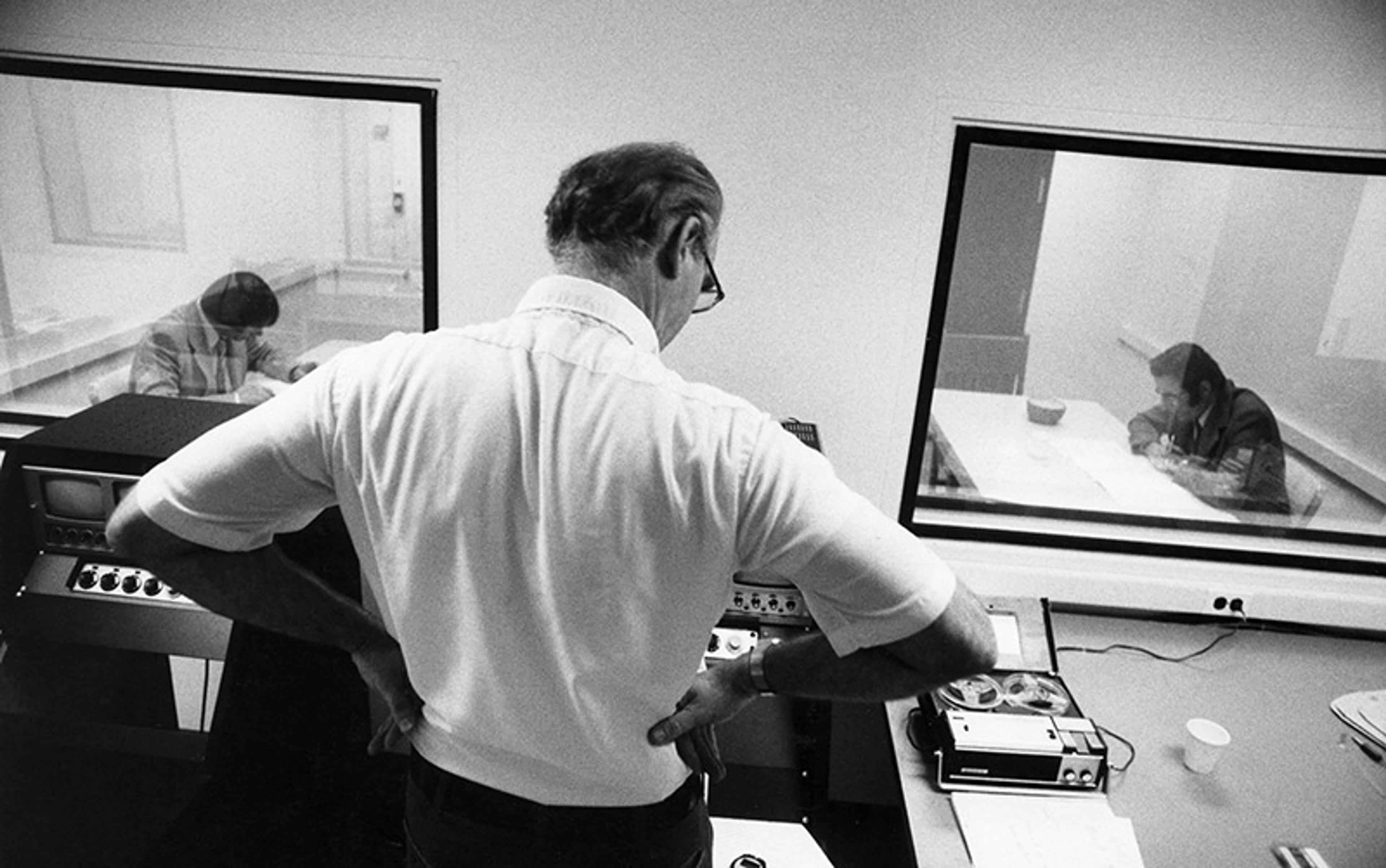

Thomas Bouchard conducting personality tests on James Lewis and James Springer, identical twins adopted by separate families, Minnesota, USA, 1979. Photo by Thomas S England/Science Photo Library

Both Jims, it transpired, had worked as deputy sheriffs, and had done stints at McDonald’s and at petrol stations; they’d both taken holidays at Pass-a-Grille beach in Florida, driving there in their light-blue Chevrolets. Each had dogs called Toy and brothers called Larry, and they’d married and divorced women called Linda, then married Bettys. They’d called their first sons James Alan/Allan. Both were good at maths and bad at spelling, loved carpentry, chewed their nails, chain-smoked Salem and drank Miller Lite beer. Both had haemorrhoids, started experiencing migraines at 18, gained 10 lb in their early 30s, and had similar heart problems and sleep patterns.

Of the 1,894 twins raised apart who had been tested by psychologists internationally between 1922 and 2018, the ‘Jim Twins’ story was, by far, the example cited most often, mainly because it seemed so strongly to suggest that nature trumped nurture, aptly illustrating Bouchard’s prior perceptions. Their tale spread around the globe, finding its way from national newspapers to The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, to school and university textbooks. Later, it was all over the web; 44 years on, it pops up whenever twins are discussed in the media, with the significant differences between these two men invariably ignored.

Some reports feature the story with two sidebar cases, also drawn from Bouchard’s twins’ larder. Oskar Stöhr and Jack Yufe were identical twins born in Trinidad in 1933, to a German mother and a Jewish-Romanian father, but they were separated six months later when their parents’ relationship broke down. Oskar was raised Catholic by his mother in Germany and joined the Hitler Youth. Jack was raised as a Jew in Trinidad by his father. They met briefly at 21 and were reunited at 47. Although they had very different world views, their speech patterns and food tastes were similar, and they shared idiosyncrasies, such as flushing the toilet before using it, and sneezing loudly to gain attention. The other sidebar is devoted to the ‘Giggle twins’, Daphne Goodship and Barbara Herbert, identical twins adopted into separate British families after their Finnish mother reportedly killed herself. They reunited, aged 40, in 1979. Unlike their adoptive families, they were both incessant gigglers, had a fear of heights, dyed their hair auburn, and met their husbands at town hall Christmas dances.

Cases such as these have been used to revive the notion that distinct upbringings make no difference in how we turn out: it’s all down to biology, specifically the clockwork mechanisms of Mendelian genetics – an idea with a long historical tail. But much has changed in our understanding of genetics since the human genome was sequenced in 2003. It was discovered that we have far fewer genes than anticipated (around 20,000, rather than the anticipated 100,000), and that there are very few genes ‘for’ anything. A complex property such as intelligence, for example, involves a network of more than 1,000 genes, interacting with the environment. Other discoveries that chipped away at genetic determinism noted that environmental pressures prompt changes in cell function and gene expression that don’t involve changes in DNA (sometimes lingering over several generations) known as epigenetics; while advances in neuroscience have revealed how our plastic human brains are moulded by experience.

Yet many of those involved in twin studies have been resistant to these influences, betraying the influence of a deeply rooted magical thinking around twins that has cast its long shadow over our understanding of the line between selfhood and otherness.

Thirty years ago, when I began writing about twins, I approached several professionals who specialised in counselling women who’d experienced multiple births, asking each of them why behavioural coincidences in identical twins occurred. Rather to my surprise, they all plumped for telepathy – like the separated conjoined twins of Alexandre Dumas’s novel The Corsican Brothers (1844), who read each other’s thoughts when apart. Joan Woodward, a twin herself and a psychotherapist, suggested that identical twins offered evidence of extrasensory perception ‘which seems to exist for some twins – a bit like these stories of Bushmen in the Kalahari walking miles to visit an uncle because they sense he’s in trouble.’

I was well aware that claims about telepathy, between twins or otherwise, failed when tested under clinical conditions, and that such mystical examples of premonitions were a good illustration of why anecdotes are not evidence. But such assertions interested me nonetheless, because idiosyncratic stories are so much part of what drives our fascination with twins. Their mystique is woven into our cultural history – perhaps because the idea of having a doppelgänger is so compelling, a mirror version of ourselves who echoes our thoughts and fears, or a companion who understands our every impulse and ensures we are never lonely. Our enchantment may also come from the perception that we have a different person inside us, the internal twin, of the Jekyll-and-Hyde variety.

Then there’s our fascination with identical twins seeming so ‘other’– a pair so attuned to each other’s way of being that one can pass for the other, hoodwinking the rest of us. Or, equally pervasive, the idea that, in order for one twin to truly thrive, he or she must destroy the other. Think of Romulus and Remus, twin sons of the vestal virgin Rhea Silvia and the god Mars, suckled by a she-wolf and united against their enemies – until they fall out over which of the seven hills to build on; Romulus kills Remus and goes on to found Rome. Or Jacob and Esau, one usurping the other’s birthright to win their father Isaac’s favour. This kind of mythologically laden thinking about identical twins in particular, combined with a steadfast belief in old-style genetic fundamentalism, has tainted the science of twin studies, with some of its leading lights faking or manipulating evidence.

The ‘Angel of Death’ would order any twins he spotted among incoming prisoners to step out for experiments

Scientists first spotted the potential of twin studies in 1875 when Charles Darwin’s polymath cousin Francis Galton wrote to 35 pairs of apparently identical twins and 20 pairs of apparently fraternal twins. He used their anecdotes to conclude that the twins who said they looked alike had similar characters and interests, whereas those who said they looked different became more so as they got older. With both sets the ‘external influences have been identical; they have never been separated,’ he said. Galton claimed his results proved that ‘nature prevails enormously over nurture’.

Galton’s work with twins reinforced his dubious belief in purifying the population, a version of ethnic cleansing that became the engine of Nazi eugenics, underpinning Josef Mengele’s notorious research in Auschwitz, involving 1,500 twin pairs. The physician known as the ‘Angel of Death’ would order any twins he spotted among incoming prisoners to step out for experiments. In one case, his assistant injected chloroform into the hearts of 14 pairs of Roma twins, after which Mengele dissected their bodies. In another, he sewed together a pair of Roma twins to create conjoined twins. They died of gangrene. In a third, he connected a girl’s urinary tract to her colon. Sometimes, he’d simply shoot them and then dissect them.

The revelations of Mengele’s crimes gave twin studies a nasty name, but the research continued because, until recently, those wanting to uncover the genetic contribution to particular traits had little alternative. Over the past few decades, twin studies have been used to test everything, from whether Vitamin C can prevent colds (it can’t) to whether homosexuality has a genetic origin (minor with gay men, and even smaller with lesbian women).

The main method of twins-based research is to compare dizygotic (DZ), or two-egg ‘fraternal’ twins, with monozygotic (MZ), or one egg ‘identical’ twins, who are more unusual – one birth in 250 (half the frequency of fraternal twins). The basis of this approach is the assumption that both groups share their environments to the same extent, but that, because fraternal twins share only half their sibling’s genes, if they show greater variation, the cause must be genetic, so it becomes possible to attach a heritability figure to it.

An example of this kind of study, involving a national sample of 11,117 twins, prompted The Guardian headline in 2013: ‘Genetics Accounts For More Than Half Of Variation In Exam Results’. Towards the end of their paper, the study’s authors noted a potential methodological drawback: to wit, ‘the equal-environments assumption – that environmentally caused similarity is equal for MZ and DZ twins’. Acknowledging the problem didn’t stop them making bold claims about the genetic contribution to exam performance. But the problem is profound, undermining hereditary claims when it comes to social studies.

The experiential gap starts in the womb because, unlike identical twins, one fraternal twin might be bigger than the other and therefore take up more space. Also, they each have their own placenta (unlike most identical twins). One meta-analytical study on the impact of the foetal environment on IQ concluded that it accounted for 20 per cent of IQ differences between fraternal twins. What’s more, the gap in experience widens as fraternal twins grow older.

A more newsworthy line of research involves comparing twins who’d been separated at birth

When I was at school, I had several twins in my classes. One pair – the Thompsons – were identical. None of us could tell them apart, and they navigated the world as a unit. Another pair – I’ll call them the Wellingtons – looked and acted differently: Amy was blonde, sporty, good looking and popular; Mary was less striking, red-haired and had just a few close friends. They seldom hung out together, were treated differently, and pursued distinct paths. These differences may have been prompted by genes, but they were widened by experience. Amy was a partygoer who spent less time studying, drank more and smoked cannabis, all of which could affect exam performance.

With the identical Thompsons, we can be sure their similar exam results were genetically prompted because their shared environment was the same and they modelled their behaviour on each other. But with the Wellingtons, their different life paths (and exam results) could be a result of genes, or of environments that became more distinct as they got older, or both. We can’t be sure.

The other, less common but more newsworthy line of research involves comparing twins who’d been separated at birth. The pioneer of this method was the British psychologist Sir Cyril Burt, a eugenics enthusiast, who claimed that IQ and other differences between races and social classes were hereditary. Burt advised government bodies on the introduction of the 11-plus exam into British schools (to sift the top 20 per cent of pupils into grammar schools, leaving the rest to fill trade-based, secondary moderns), and pushed them to include an IQ test, insisting that IQ was innate. He based his conclusions on studies of separated identical twins that he claimed to have conducted with three assistants in the 1950s and ’60s.

Shortly after he died in 1971, Burt’s records and notes were all burnt, after which his reputation imploded. Two of his researchers, whose names appeared as co-authors on his papers, could not be traced (when asked about them, Burt had said they’d both ‘emigrated’ – but he didn’t know where) and a third he clearly invented. In The Science and Politics of IQ (1974), the American psychologist Leon Kamin noted that in 1955, when Burt claimed to have tested 21 separated identical twins, he put the correlation between their IQs at 0.771, yet in the 1960s, when his twins cohort numbered 53, he gave the identical three-decimal figure, which Kamin said had a statistically minuscule chance of occurring. Some circumstantial details that Burt claimed to have found among his twins also raised eyebrows: of a pair born to a wealthy mother and then adopted, he claimed one was raised in splendour on a Scottish country estate, and the other was left to a shepherd (like Perdita in The Winter’s Tale). The killer blow was delivered by his approved biographer, Leslie Hearnshaw, a one-time Burt enthusiast who in 1979 concluded that all of Burt’s twin studies were invented.

The next big wave of studies of separated twins came from the stable of Bouchard, the hereditarian behind the ‘Jim Twins’ revelations. Bouchard was attracted to race science and, in 1994, he publicly endorsed a document drawn up by the race science promoter Linda Gottfredson: ‘Mainstream Science on Intelligence’. Its purpose was to back Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s book The Bell Curve (1994), which argued that poverty was caused by low IQ and that this was the reason why there were more poor Black people. Bouchard also wrote an enthusiastic endorsement for an overtly racist book called Race, Evolution, and Behavior (1995) by the Canadian psychologist J Philippe Rushton. Bouchard received financial backing for his twin studies from the Pioneer Fund, set up in 1937 by Nazi supporters. The Fund maintained its policy of promoting research in eugenics and ‘race betterment’.

Race science promoters were drawn to twin studies because they thought that, if it could be shown that IQ was highly heritable, then different IQ averages between population groups could be portrayed as innate. But this assumption misunderstands heritability, which speaks to the degree of variation in a trait directly caused by genes within a population, never between populations. This can be illustrated using something far more heritable than IQ: height. Two populations with the same gene profile might have different height averages for environmental reasons. For instance, South Koreans are up to 8 cm taller than North Koreans because of better nutrition over several generations. In the same way, two populations might have different IQ averages owing entirely to environmental factors – something that Bouchard’s backers failed to appreciate.

Using Pioneer Fund money, Bouchard’s Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research built up its larder of twins raised apart, inviting them in for a battery of interviews and tests. His research team ended up grilling 81 pairs of identical twins and 56 pairs of fraternals. Bouchard’s results must have delighted his sponsors because he said adult IQ was 70 per cent heritable (later he opted for an overall figure of 50 per cent). But his methods and conclusions did not impress other researchers. One problem was self-selection. His identical twins had known each other for an average of nearly two years before contacting him; some had known each other as young children; and it seems likely that those who were most alike were most likely to contact him. Kamin, the professor who rumbled Burt’s fraudulent studies, and his colleague said there was pressure on the twins to come up with cute stories, and that Bouchard’s studies had ‘a number of serious problems in the design, reporting, and analyses’.

Numerous scientists have questioned the value of heritability estimates for social phenomena

Another issue is that Bouchard’s heritability score was based on ‘the assumption of no environmental similarity’ even though almost all the twins in his studies were raised in aspirant, white, middle-class environments, often living near one another, with relatives. Richard Nisbett, a psychology professor at the University of Michigan who specialises in IQ, argued that this false baseline insistence that all adopting families were different led to an overestimation of heritability. ‘Adoptive families, like Tolstoy’s happy families, are all alike,’ he said in an interview with The Times in 2009. Incidentally, Bouchard acknowledged that his percentages applied only to the ‘broad middle class in industrialised societies’, which seemed to contradict his ‘no environmental similarity’ assumption.

Bouchard’s claim that the heritability of IQ increases as twins get older – when true IQ potential kicks in – is equally problematic. Jim Flynn, perhaps the leading IQ theorist of the past half-century, disagreed. In his book What Is Intelligence? (2012), he used the example of separated identical twins born with sharper-than-average brains – prompting them to go to the library, get into top-stream classes, and attend university – to disavow the notion that ‘identical genes alone’ will account for their similar adult IQ scores, and suggesting instead that ‘the ability of those identical genes to co-opt environments of similar quality will be the missing piece of the puzzle.’ Flynn places this ‘multiplier effect’ squarely in the environmental column.

Numerous scientists have questioned the value of heritability estimates for social phenomena – both because it is impossible to separate genetic and environmental prompts, and because it depends on how a population is defined: the wider the definition, the lower the heritability percentage. Bouchard acknowledged that non-middle-class environments might reduce heritability estimates, and that his percentages should therefore ‘not be extrapolated to the extremes of environmental disadvantage’. The British neuroscientist Steven Rose put it more bluntly: ‘Heritability estimates become a way of applying a useless quantity to a socially constructed phenotype and thus apparently scientising it – a clear cut case of Garbage In, Garbage Out.’

It would seem that genes are less predictive of human behaviour than once thought – at least this is what is emerging from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that find genetic markers for alleles that influence a trait within a particular population, producing a ‘polygenic score’. Thus, a study of 54,888 Icelanders published in Nature Genetics in 2018 found the heritability of educational attainment was 17 per cent (compared with 50 per cent-plus from twin studies) .

The academic psychologist Kathryn Paige Harden, who uses twin studies and GWAS methods, acknowledges that both these forms of social research may over-egg heritability. ‘There are questions with the twin studies about whether they are attributing to genes what should really be claimed by the environment,’ she told The Observer in 2021. ‘And for polygenic score studies, people may just happen to differ genetically in ways that match environmental factors, and it is really those that are driving the effect.’

If people with identical genes are raised in similar environments, it is likely their IQs will also be similar. But what would happen if they were raised in diverse environments like the twins in The Corsican Brothers – one raised by a servant in the mountains; the other as a gentleman in Paris? Despite his own hereditarian bias, Bouchard’s research suggests the answer. In one paper he referred to separated identical twins with an IQ gap of 29 points; in another, 24 points.

What about both smoking Salem cigarettes, owning dogs called Toy, and having wives called Linda and Betty?

More recently, two pairs of Colombian identical twins were raised as fraternal twins after being mixed up in a hospital error: one pair was raised rurally in a poor family near La Paz, the other pair grew up in a lower-middle-class family in cosmopolitan Bogotá. When they met in 2014, initial reports focused on their similarities. But when Yesika Montoya, a Colombian psychologist, and Nancy Segal, an American academic psychologist who’d once been Bouchard’s lead researcher, persuaded all four men to sign up for a batch of interviews, IQ tests and questionnaires, they discovered that the twins were even less alike than anticipated. ‘The Colombian twins really made me think hard about the environment,’ Segal told The New York Times in 2015. Later, she told The Atlantic: ‘I came away with a real respect for the effect of an extremely different environment.’ A similar experience with a pair of Korean identical twins confirmed Segal’s appreciation of ‘cultural influences’. ‘They really do have a strong effect,’ she told The Telegraph in 2022. ‘But they don’t blot out the basic similarities.’

Yet it is all too easy to pounce on those similarities and overstate their significance, and then brush aside differences. The Jim Twins are an example. There are clear genetic links to heart problems, migraines, weight gain, sleep patterns, nail-biting and probably to maths preference too. Other parallels can be explained at least in part by the Jims’ similar home environments, including shared holiday destinations, job overlaps and car choices. But what about both smoking Salem cigarettes, owning dogs called Toy, and having wives called Linda and Betty? Pure chance. In nearly 2,000 studies of twins raised apart, coincidences inevitably emerge, but no studies uncovered anything like the level of overlap found with the two Jims.

Put it all together, and it would seem that using twins to discover heritability percentages for human behaviour is inherently unreliable. The usual method, of comparing identical and fraternal twins falters because it cannot calculate the impact of the diverging environments experienced by most fraternal twins. The esoteric method of comparing twins raised apart may produce tasty anecdotes, but it has even more profound problems, starting with the small, self-selecting sample and the false assumption that their home environments differ substantially.

Twin studies are still widely used and may remain useful in trying to find out the heritability of illnesses and other physical outcomes where the environmental component is unlikely to differ between identical and fraternal twins. But there is a huge gap between attaching a heritability percentage for, say, macular degeneration, and for something like IQ or academic performance, where it’s impossible to untangle the interlocking influences of biology and culture.

Even the Jim Twins, raised by similar families, in the same part of the same state, have their own stories to tell because of their unique upbringings. Focus on these, and a different picture emerges. When they first met, they had distinct hairstyles and facial hair (one a bit Elvis, the other more Beatles) and different kinds of jobs. Their children were of different ages and most had different names. Springer stayed with his second wife, Betty, while Lewis married a third time. More significantly, they displayed marked character differences, noticeable to anyone who met them: Springer, the more loquacious of the brothers, called himself ‘more easy-going’ and said Lewis was ‘more uptight’. Lewis was reticent in public and, in private, he preferred to write down his thoughts.

Much of the magic evaporates when we lift the lid on the sensational tales of parallel lives. What emerges in place of this seductive mirror myth of the hidden double are more mundane tales of everyday difference, revealing the unique selfhood that is part of the inheritance of all people – including those with genetic doppelgängers.