‘I have the feeling that I am an unofficial reporter covering a shipwreck,’ wrote the Dutch Jewish journalist Philip Mechanicus on 29 May 1943, from the Westerbork transit camp on the sodden soil of Drenthe in the northeastern Netherlands. He’d been a prisoner at the camp since the previous November, after he was arrested for appearing in public in Amsterdam without the yellow Star of David affixed to his jacket.

Mechanicus was a 54-year-old seasoned journalist, foreign desk editor for the national newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad, who had written from Indonesia, Russia and Palestine as a foreign correspondent. It may have been his reputation that did him in – someone recognised him on the street and informed on him. After his arrest, he was sent to Amersfoort Polizei-Durchgangslager, a German punishment camp, where he was apparently tortured. The details are not known but, when he arrived at Westerbork two weeks later, he weighed 80 pounds and both his hands were broken.

‘Gradually, I have developed the notion that I wasn’t brought here by my persecutors, but that I took the trip voluntarily to do my work,’ he continued. One hand, at least, had healed enough so that he could write. ‘I’m busy all day long, without a second’s boredom, and sometimes I feel as if I have too little time. Duty is duty; work ennobles.’

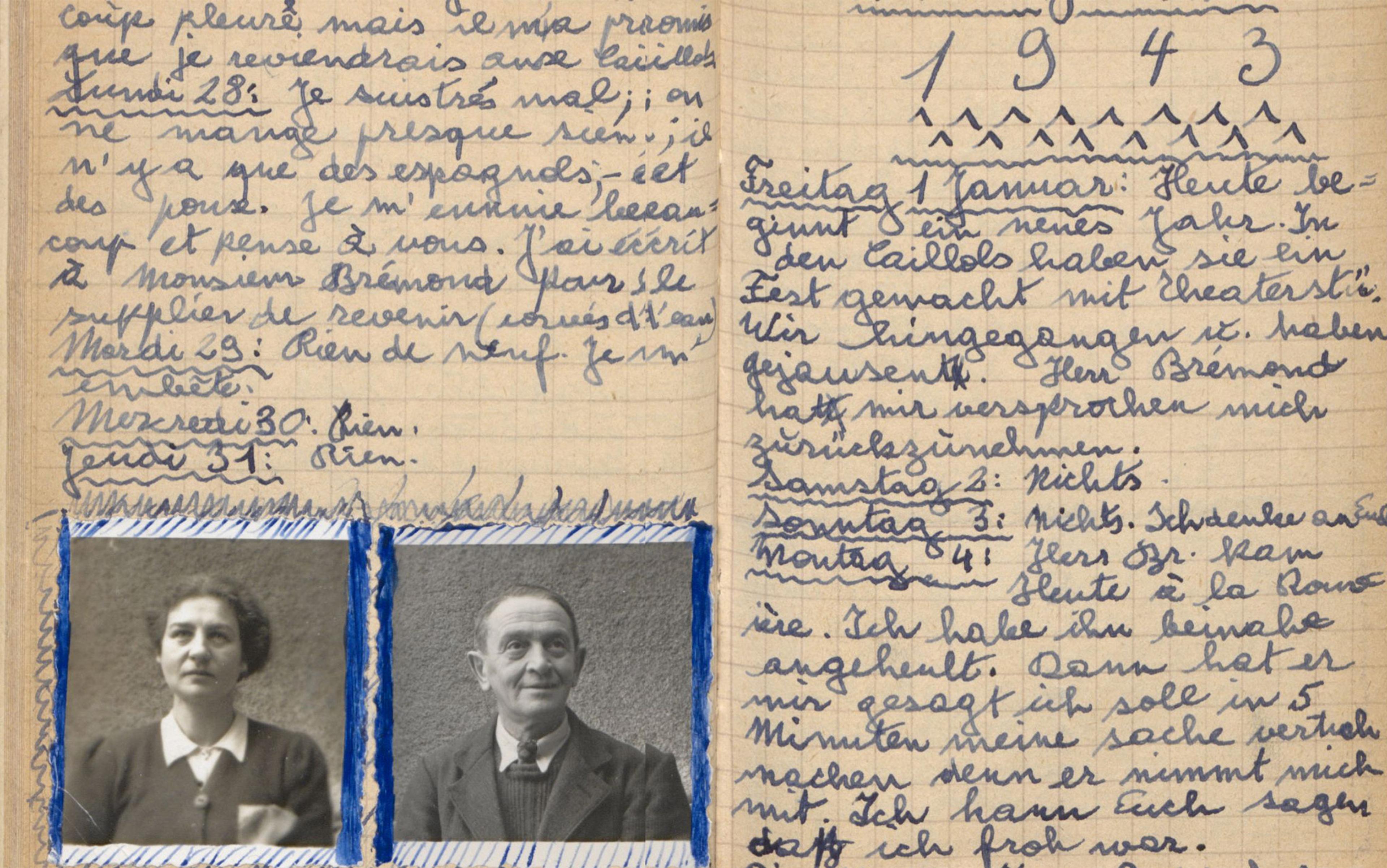

He scribbled his words into a thin school exercise book with a blue cover that he’d got from the camp school. It was one of 15 such notebooks that he would use to jot down his daily impressions of life at Westerbork during the 17 months that he remained at the camp, before being deported ‘on’ to Bergen-Belsen and ultimately to Auschwitz, where he was shot and killed.

Mechanicus was aware of his predicament; he managed to avert deportation for almost a year and a half, and during that time he produced what is undoubtably the most valuable eyewitness account of Westerbork camp in operation, a record of daily life for the tens of thousands of Jews temporarily housed there, before they were shipped off to their deaths.

Today, Mechanicus’s diary is one of more than 2,100 in an Amsterdam collection held at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, housed in the underground archives of a grand, doublewide mansion on the Golden Bend of the Herengracht Canal. The NIOD collection didn’t come together by accident. It was part of a concerted effort to collect, preserve and potentially publish the personal correspondence of ordinary citizens living through the occupation.

The idea to do so was hatched simultaneously by Loe de Jong, a Dutch Jewish journalist in exile in London, who worked for Radio Oranje, the broadcast station for the government in exile, and a group of local Dutch scholars led by the economics and social history professor, Nicolaas Wilhelmus Posthumus, who had already established a few archives of social movements.

More than a year before the war ended, De Jong had convinced the exiled Dutch Cabinet to establish a study centre of the occupation; it would open its doors as soon as the war ended. On 28 March 1944, Gerrit Bolkestein, the Dutch minister of education, arts and sciences, addressed the nation on Radio Oranje, in a speech that De Jong had written for him.

,_Bestanddeelnr_935-0610.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Loe de Jong at work in London in 1942. Courtesy Wikipedia

‘History cannot be written on the basis of official decisions and documents alone,’ said Bolkestein to his countrymen back home. ‘If our descendants are to understand fully what we as a nation have had to endure and overcome during these years, then what we really need are ordinary documents – a diary, letters.’

Diaries and letters were often deemed suspect because they were tainted by experience

It was a relatively new notion that personal documents could illuminate history. Scholars of the early 20th century, above all, valued ‘objectivism’, a concept developed by the 19th-century German historian Leopold von Ranke, who sought to turn ‘historiography’ into a scientific discipline; this required ridding it of its moral dimension. Ranke argued that facts were central to objective history-writing and, to maintain a scholarly distance from facts, historians should eliminate personal bias and take a neutral attitude. But, between the two world wars, this notion of ‘objectivism’ was already losing its grip. Official documents kept by the Germans as part of their notoriously meticulous record-keeping project, for instance, were naturally subjective in their advancement of Nazi aims.

A more accurate way to differentiate between subjective and objective documentation would be through the prism of power. Sources considered ‘objective’ were typically associated with the dominant power elite; documents like diaries and letters, oral histories and first-hand witness accounts, by contrast, were often deemed suspect because they were tainted by experience.

In their book Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History (1992), the psychiatrist Dori Laub and the literary critic Shoshana Felman argued that the Holocaust was an ‘event without a witness’ because anyone who had witnessed the Nazi concentration camp system first-hand could no longer be regarded as sane. The victim’s exposure to a brutal and delusional ideology ‘eliminated the possibility of an unviolated, unencumbered, and thus sane, point of reference’.

German police round up Jewish men at Jonas Daniël Meijerplein, a square in Amsterdam, in February 1941. Courtesy Wikipedia

But in the midst of the Second World War, a period of extreme propaganda, totalitarian media control and widespread rumour – what the theorists term ‘epistemic instability’ – the individual voice began to emerge as a counterweight to the dominant public narrative. That voice, in turn, formed a chorus of testimony. A personal narrative about the Warsaw ghetto soup kitchen, for example, would combine with another, like a poem about the carousel outside the Warsaw ghetto, to make a social memory – a memory of a group of people whose stories were ignored, disregarded or forgotten. The French philosopher and sociologist Maurice Halbwachs suggested that these small, atomised memories of a communal experience formed a ‘collective memory’ – a term he coined between the two world wars – that could be a history that ran counter to the dominant historical narrative. Individuals remember, and then the group constructs the memory for the whole.

Photographs, memoirs, diaries, poetry, letters, children’s drawings were buried underneath the ghetto

In the Netherlands, Posthumus pioneered the notion that an individual’s voice could contribute to the construction of history as a whole. In 1935, he established the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, as the Nazis rose to power in Germany. His aim was ‘to acquire archival treasures from the possessions of the hunted and the defrauded’ in a time of ‘political crisis and persecution’. Almost immediately after the Nazis invaded Holland, Posthumus began collecting source material from the citizen’s point of view. His National Bureau for War Documentation, secretly launched in an Utrecht café, was up and running by 1944.

Others were thinking in much the same way. Before the 1942 liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, a group of writers, journalists and archivists led by the Polish Jewish scholar Emanuel Ringelblum collected as much material as possible – photographs, memoirs, diaries, poetry, letters, children’s drawings – and buried it underneath the ghetto. Today that extraordinary trove, Oneg Shabbat, is probably the world’s largest recovered archive of Jewish prewar and wartime documentation. Similar collections were discovered from the ghettos of Vilna, Białystok, Łódź and Kovno.

‘In hundreds of ghettos, hiding places, jails, and death camps, lonely and terrified Jews left diaries, letters and testimony of what they endured,’ says the historian Samuel D Kassow in his book Who Will Write Our History? (2007). ‘For every scrap of documentation that surfaced after the war, probably many more manuscripts vanished forever.’ The workers for the Oneg Shabbat realised, he wrote, that they ‘might be writing the last chapter of the 800-year history of Polish Jewry’.

Isaac Schiper, a leading Polish Jewish historian of the interwar period, understood the value of these materials not just for telling the Jewish side of the story, but for establishing the future of history. ‘Everything depends on who transmits our testament to future generations, on who writes the history of this period,’ he told his fellow inmate at Majdanek concentration camp, not long before he was killed. ‘Should our murderers be victorious, should they write the history of this war, our destruction will be presented as one of the most beautiful pages of world history, and future generations will pay tribute to them as dauntless crusaders. Their every word will be taken as gospel. Or they may wipe out our memory altogether, as if we had never existed…’

There was a danger, too, that the cry in the dark would not be heard, according to Schiper. ‘[I]f we write the history of this period of blood and tears – and I firmly believe we will – who will believe us? Nobody will want to believe us, because our disaster is the disaster of the entire civilised world …’

The civilised world was jettisoned in the Holocaust but, by collecting witness testimonies, first-hand memoirs and other personal artefacts attesting to the lives of those who would soon die, some hope could be extended to Jewish communities facing extinction. A new form of ‘history of the present time’ arose in the aftermath of the First World War, wrote the Egyptian French historian Henry Rousso in The Latest Catastrophe (2016), out of a need to explain the vast destruction of civilian populations, attacks on noncombatants, massacres of prisoners of war, and demolition of nonstrategic urban centres. ‘The terrible question had to be confronted: how to preserve the memory of the dead and disappeared without sepulchers, how to come to terms with the collective losses, give meaning to events that seemed beyond the reach of reason?’

The Second World War was not merely a military conflict but ‘an extraordinary assault on civilians’, wrote the historian Peter Fritzsche in his book An Iron Wind: Europe Under Hitler (2016), a work that relied heavily on first-person documentation, including many diaries. The war’s ideological violence played out in urban centres, in public squares, on public transportation, and inside businesses and homes. Often, it was characterised by civilian betrayals among neighbours, even within families.

‘The war erased whole horizons of empathy,’ according to Fritzsche. It fundamentally altered human relationships and, as such, it was intimate, personal and close to home. The result was that a great number of citizens felt compelled to write about these experiences, for themselves, and for future generations. ‘Across Europe diarists recorded the conversations and rumours they heard and the impressions they gathered,’ wrote Fritzsche, and many of those writings survived.

In the aftermath of two calamitous world wars, humanity needed new forms of history writing

Historians of the postwar era recognised that they had a role in shaping the new collective memory, as a way not just to record events, but to transform human behaviour, to try to heal society. This new way of writing recent history emphasised what Carolyn Jean calls the ‘moral witness’, voices of survivors who could speak on behalf of the dead, because the dead had a lesson to impart to humanity.

In his Aeon essay about the German historian Reinhart Koselleck, Stefan-Ludwig Hoffman writes: ‘Dismantling the concept of history and coming up with a new theory of how histories actually unfold – chaotic, contingent, messy and ferocious, yet with discernible patterns – was therefore the most important task for historians.’ Koselleck had been trained as a Hitler Youth, sent by the Nazis to the Eastern Front, and survived Stalin’s Gulag, emerging as a pivotal thinker of the postwar era. He understood that, in the aftermath of two calamitous world wars, humanity needed new forms of history writing. A form of history writing that was objective in the extreme could lead to the dangerous formation of ideologies – and, as the wars had shown, ideological differences could lead to catastrophic social rupture.

Koselleck argued for an open-ended discourse between the objective and subjective. The professional historian who reconstructs history ‘impartially’ can claim the domain of objective truth, but, as Aleida Assmann wrote in 2010, individuals also have a right to claim their own subjective truths, drawn from specific, distinctive and authentic memories. By forcing these different types of truth into conversation with one another, historians could attempt to close the gap.

After the Second World War ended, these historians and theorists tried to implement their new notions of the history of the present moment, quite quickly. The Dutch government officially founded the National Bureau for War Documentation (later renamed NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies), on 8 May 1945, just three days after Liberation. People from all walks of life arrived to donate their notebooks, scrapbooks, collections of battered loose pages, index cards dug up from holes in the ground, unsent letters, drafts of memoirs, personal photographs, and notes scribbled on Monopoly money and cigarette rolling papers.

The NIOD’s founders actively solicited materials through a radio and poster campaign, too, and went door to door asking people to submit their personal documents. De Jong, who was appointed director of the NIOD in October 1945, personally travelled across the country soliciting submissions, including from former collaborators, from leaders of the Dutch Nazi party and from Hanns Albin Rauter, the head of the German police in the Netherlands. Materials could also be dropped at the central office on the Herengracht, or at additional bureaus in The Hague and even in Batavia, the capital of the colony then known as the Dutch East Indies, now Jakarta in Indonesia.

The Netherlands was the first country to actively preserve such materials from the war era, a pioneer in focusing on the individual, civilian, subjective experience of the occupation, but many other European countries quickly followed suit, including France, Italy, Austria and Belgium. ‘Everywhere in Europe, often at the impetus of the state and on the margins of the academic world, history institutes and committees were created with the mission of collecting documents and testimony and of producing the first histories of an event that had only just ended,’ Rousso wrote.

De Jong set up a Diaries Department at the NIOD in March 1946, led by his deputy director, A E Cohen, who strove to ensure that ‘all categories of diaries’ would be represented among those preserved. This meant he wanted journals written by farmhands and schoolteachers, wealthy landlords and poor ragpickers, Nazi sympathisers and communists – people from all walks of life. They ‘need not be many but they should be various’, Cohen wrote.

The collection was not only amassed but also curated. The NIOD would read and review each submitted diary and decide whether or not to keep it, copy it, or return it. Whether retained or not, each diary handed in to the NIOD received a number. By the end of the 1950s, it had logged #1001.

Anne Frank’s diary stands alone as a work of literature, but it is also part of a larger collective memory

Anne Frank’s diary was assigned #248, when the NIOD noted efforts to obtain the original, but it didn’t come into their collection until 1980, when Otto Frank died and bequeathed all of his daughter’s manuscripts and three photo albums to the Institute. First published in Dutch in 1947 as Het Achterhuis [‘The Secret Annex’]: Dagboekbrieven van 14 Juni 1942–1 Augustus 1944, and later translated into English as Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl (1952), it subsequently became one of the most translated books in the world, a defining personal document of the Second World War. Frank’s diary alone proved the theorists correct: to make an impact, history must be told from a subjective perspective.

Frank’s diary stands alone as a work of literature, but it is also part of a larger collective memory created by the entire diary collection at NIOD, and part of the story of the Dutch Jewish community who died in the Shoah. While Frank’s diary falls silent when she was arrested on 4 August 1944, the rest of her journey is filled in through the writings of others who followed a similar path to the death camps.

Mechanicus gave us a view of Westerbork, where Frank and her family would spend just under a month, before they were put on the last transport to Auschwitz on 4 September 1944. His journals were smuggled out of the camp somehow, to his ex-wife, Annie Jonkman, a non-Jewish woman who lived in Amsterdam with their daughter, Ruth, a resistance fighter. Thirteen of his 15 journals survived the war and, once Jonkman learned of the NIOD’s campaign to collect wartime diaries, she hand-delivered her late ex-husband’s to De Jong; it was added to the collection as #391.

‘How grateful we must be to him for not wanting to be anything more than the man who goes about with his notebook, noting down events from day to day,’ wrote the Dutch historian Jacques Presser, in his prologue to Mechanicus’s diary, published in Dutch as In Dépôt (1964); in English, Waiting for Death (1968). ‘In fact, [he was] a war correspondent setting down his record while his life was constantly in danger, although he hardly ever seemed to realise it.’

The writings of those sinking, shipwrecked, submarined diarists were a hope in a bottle

The first surviving diary entry from Mechanicus’s life in Westerbork was dated Friday, 28 May 1943, in a journal labelled #3, as two previous journals were lost. His second was about the ‘shipwreck’. ‘We sit together in a cyclone, feeling the ship leaking, slowly sinking,’ he elaborated on 29 May, ‘yet, we’re still trying to reach a harbour, though it seems far away.’

The shipwreck metaphor was employed frequently by Jewish diarists to describe their sense of impending catastrophe. The Oneg Shabbat archivist Rachel Auerbach wrote that the ‘scenes of panic’ in the Warsaw Ghetto will ‘vanish with the sinking ship, or with a burning house from which nobody manages to escape, or from a coal pit at the time of an explosion, when the bodies of the miners are buried alive’. The Polish Jewish poet, lyricist, journalist and actor Władysław Szlengel, who organised cultural activities in the Warsaw Ghetto, also described the inhabitants as trapped sailors in a submarine accident.

‘When Jews compared themselves to trapped miners or shipwrecked sailors, they emphasised the fact that their physical connection to the rest of the world had become broken,’ writes Fritzsche in An Iron Wind, while at the same time affirming ‘their existential connection to the readers who would pore over their last words.’

Oskar Rosenfeld, an Austrian Jewish playwright and journalist in the Łódź ghetto, observed that the writings of those sinking, shipwrecked, submarined diarists were a hope in a bottle: ‘They did not know where [their records] would be washed up nor by whom it would be read.’

Sometimes their words, at least, did reach another shore – the beaches of another time, the future. Together, their words provide us with a collective memory, of a society on the brink. Their jottings, scribblings and cries in the dark give us not just an understanding of the Jewish community at the edge of disaster, but of a continent sinking under the weight of its own hatreds, cruelties and self-delusions. In other words, the fate of ‘the entire civilised world’.

If only these testimonies were enough to convince the civilised world to refrain from genocide and crimes against humanity. Despite ample evidence of atrocities of the past, and cries of ‘never again’, we have, since the Second World War, seen many more cataclysmic events that require us to learn from eyewitnesses – victims, perpetrators and bystanders. Historians and sociologists are still recording testimonies from the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and the 1995 Srebrenica massacre of Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims); they are attempting to collect eyewitness accounts from the ongoing violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar. And who knows what kind of accounts will emerge from the Uyghur population and other mostly Muslim ethnic groups, now being held as captives in Xinjiang, northwestern China. Ukrainians both inside and outside their home country, still under attack a year since Russian bombardments began, have turned to modern tools to record their personal accounts – online diary blogs and podcasting.

The urge to record such moments of crisis – to reveal the personal in the public realm – persists. Mila Teshaieva, a Berlin-based Ukrainian artist who returned to her home country to record a diary of daily life in the embattled country, said that wherever she found people under bombardment, in Bucha and Borodyanka, she found people writing diaries. ‘I met a number of people, very simple people, who actually never write diaries, but in this time, especially in places under occupation, they started writing diaries,’ she told me. ‘It was not because they wanted to keep a record, but because they were thrown out of their lives. They hear explosions and gunshots, and Russian tanks are rolling past. They needed to make some sense of their daily lives.’ Diaries help them do that.