‘You take delight not in a city’s seven or 70 wonders, but in the answer it gives to a question of yours.’

– from Invisible Cities (1972) by Italo Calvino

Unlike other great cities of ancient fame such as Rome, Athens or Jerusalem, Sparta seems to have disappeared off the map. What remains of the legendary town? A name? An archaeological site? A historical memory? That memory, if it exists at all, is often of a city-state with a mania for martial valour and athleticism, a distrust of foreigners, and extreme austerity. It’s popularly captured today in the phrase ‘This – is – Sparta!’ as shouted by Gerard Butler, playing King Leonidas in the film 300 (2006) when he kicks the Persian messenger into a well.

It is not only in modern times but since antiquity that the perception of Sparta has been, in quite a radical sense, skewed. The book Le mirage spartiate (1933) by François Ollier traces the history of these misconceptions of a city with an elite male class of Spartiates dedicated solely to war, and women supposedly throwing weak newborns off the cliffs around Mount Taygetus. Such fires were fuelled by authors such as Xenophon, Plato, Aristotle and Plutarch, all of whom were non-Spartan and some of whom were explicitly hostile to Sparta.

View from the Byzantine ruins of Mystras towards modern Sparta, August 2020. Photo by Athanasios Gioumpasis/Getty

In order to understand this shadowy town, we need to move beyond the idea of a warfare-oriented polis and consider instead her many invisible cities. There is no single Sparta. Indeed, Sparta, like many cities, is akin to the Ship of Theseus, a philosophical paradox posed by Plutarch (46-119 CE). A ship is preserved by the Athenians, who replace the old planks with new planks as they decay. The paradox is whether, by replacing the decaying planks, the ship can still be considered the Ship of Theseus or whether (and when) it becomes something else entirely.

Italo Calvino has a different approach in his novel Invisible Cities. The character of Marco Polo in his text describes 54 cities with female names, which in the end are all one: Venice. At Sparta, where we impose the ideal of one particular history, there is a palimpsest of other cities to be explored. The view from the stoas of the dynasty of the Euryclids, Sparta’s Greek governors during the Roman period, would be very different indeed from the ruin-studded landscape traversed by 18th-century travellers hoping to commune with antiquity, and different again from the grand feasts held at the legendary palace of King Menelaus and beautiful Helen. By peeling back, one by one, these layers of time, Sparta’s story can be scrutinised against our preconceptions, and written anew.

Long before King Leonidas, Sparta was famed as the home of the most beautiful woman in Greece, Helen, and her husband Menelaus. Homer himself describes their glittering palace, which Telemachus, Odysseus’s son, visits in search of news of his father.

In awe at the splendour of the palace, Telemachus whispers to his friend:

Dear friend, do you see how

these echoing halls are shining bright with bronze,

and silver, gold and ivory and amber?

It is as full of riches as the palace

of Zeus on Mount Olympus!

– from the 2017 translation of the Odyssey by Emily Wilson

In addition to the royal household, Lakonia – the land where Sparta is found, in the south of the Peloponnese – is described with the epithets ‘hollow’, referring to the Eurotas valley in which the town sprawls into existence, and ‘filled with ravines’, as modern rock climbers in the area will know. From earliest times, we see, then, how Sparta was an important and famous site in the Greek world, and made legendary by Homer even long before the Persian Wars.

Recent archaeological excavations bring the words of Homer to life. South of Sparta, situated on a hill known as Ayios Vasileios, near the village of Xirokambi, the remains of an enormous Mycenaean palace complex, rich in finds, were discovered in 2008. The site is exceptional, for it is the only Mycaenean palace complex to have been uncovered in Lakonia to this date. Archaeological research has revealed that the site functioned as a palace complex from the 17th century BCE, continuing to grow in size and importance until its fiery demise at the beginning of the 13th century BCE.

The power of the kingdoms crystalised into myths, later preserved in the Homeric epics

Its destruction is precisely the reason for the preservation of one of the most fascinating finds, an archive of clay tablets in Linear B (a syllabic script used for writing Mycenaean Greek, and the earliest attested form of the Greek language), which were fired during the palace’s demolition. Most of the tablets seem to be of a bureaucratic function, used by the palace administration to keep track of property and goods. The discovery of a cache of 20 bronze swords speaks to the military prowess and dominance of the palace’s elite, who likely had control of much of the surrounding fertile land. Other finds that reveal the flourishing wealth and influence of Lakonia’s Mycenaean palace include vibrantly coloured fragments of wall paintings, Egyptian scarabs, and a decorated bull’s head rhyton, which could have been used for making offerings to the gods.

The material evidence paints a picture of the Eurotas valley as the home of Mycenaean kings, lording over a fertile valley. The power of the kingdoms crystalised into myths, later preserved in the Homeric epics: the first iteration of Sparta.

From 700 BCE onwards, exquisite carved ivories, enormous bronze tripods and painted temple sculptures appear at Sparta’s sanctuary sites. Scarabs of Egyptian faience and masks of Phoenician influence now gave Sparta a cosmopolitan flavour. Famous artists, such as the bronzeworker Gitiadas, purportedly of Spartan origin, and Bathykles, coming all the way from Magnesia in Asia Minor, were commissioned to adorn these very same sites with their works. During this time, Spartan pottery had a Mediterranean market, appearing in North Africa in Cyrene, as well as all over Magna Graecia (southern Italy). Material culture speaks to a society engaged in trade and invested in images – of myth and of themselves.

Our scant literary evidence from the 7th century BCE comes from two Spartan poets, Alkman and Tyrtaios, primarily in the form of songs, and intended to be performed in front of the community at religious festivals and drinking parties. In an excerpt from Alkman’s most complete fragment, known as the ‘first partheneion’, and thought to have been performed by young Spartan girls on the cusp of adulthood, the emphasis is on beauty, both of the girls and the objects which adorn them (a snake-bracelet, a headdress, eye make-up):

But whoever is second to Agido in beauty,

let her be a Scythian horse running against a Lydian one.

…

It is true: all the royal purple

in the world cannot resist.

No fancy snake-bracelet,

made of pure gold, no headdress

from Lydia, the kind that girls

with tinted eyelids wear to make themselves fetching.

As Alkman demonstrates, ‘luxurious’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ are appropriate words to describe Sparta during the Archaic period – an importer of art and artists from the Near East, and an exporter of their own works across the eastern Mediterranean. Sparta was a culture that fits into the broader picture we have of the region, of kingdoms and city-states competing with each other, trading with each other, becoming aware of their own idiosyncrasies and their relationships to others. There’s no place for austerity here, the second iteration. Although warfare was a part of life, as the subjugation of the neighbouring population of Messene suggests, song, dance and beautiful objects were equally important.

But what about the classic image of Sparta, then, where luxury is eschewed, state secrecy is prized, and the sole focus of the male populace is training for battle? Now it’s time to consider what we know about Sparta in the period she is most known for. Does representation hold up to reality? It’s a question that stays open for the intrepid (or, perhaps, the delusional) to take a stab at.

The problem with painting a ‘true’ picture of classical Sparta is our sources. Nearly all our literary sources are non-Spartan. There is either explicit hostility towards the polis, or else idealisation. At the same time, archaeological evidence from the period is notably scant – a fact exacerbated by the building of the modern town of Sparta over the ancient. The absence of historical fact invites room for imagination.

The Acropolis is a major tourist destination but few are aware that Sparta still exists as a modern town

There is, however, one quotation from the ancient historian Thucydides, remarkable for its seemingly prophetic nature. In the passage, Thucydides undertakes a thought experiment that describes exactly the situation with which both present-day reality and classical scholarship agree:

Suppose, for example, that the city of Sparta were to become deserted and that only the temples and foundations of buildings remained, I think that future generations would, as time passed, find it very difficult to believe that the place had really been as powerful as it was represented to be. Yet the Spartans occupy two-fifths of the Peloponnese and stand at the head not only of the whole Peloponnese itself but also of numerous allies beyond its frontiers. Since, however, the city is not regularly planned and contains no temples or monuments of great magnificence, but is simply a collection of villages, in the ancient Hellenic way, its appearance would not come up to expectation. If, on the other hand, the same thing were to happen to Athens, one would conjecture from what met the eye that the city had been twice as powerful as in fact it is.

Thucydides imagines an abandoned Sparta, suffering under the ravages of time. He foresees that its material remnants, today’s archaeological remains, would be unimpressive to future generations. It’s uncanny that this is precisely what has come about, with the Athenian Acropolis as a major tourist destination, while few are aware that Sparta still exists as a modern town, much less as anything worth seeing.

His statement that the city ‘contains no temples or monuments of great magnificence’, however, deserves to be interrogated further, especially in light of the literary evidence from the travel writer Pausanias, who, in the 2nd century CE, describes some magnificent structures indeed. Even in the case of Thucydides, the so-called father of history, it’s worth questioning the motives that lead him to present Sparta as he does. As an Athenian himself, Thucydides might purposefully wish to emphasise the distinction between urbane and ostentatious Athens and simple, quasi-rural Sparta, the two main powers of the greatest war Hellas had ever seen. In this context, it behoves the historian to underscore not possible similarities, but differences. When we take such statements as objective fact, instead of understanding that the historian is himself aware of his power in shaping history, many sides of the story can get lost.

I’m not denying that Sparta was different, and even exceptional, in comparison with other Greek poleis, or that the Battle of Thermopylae (480 BCE) was not a determining event in world history; or even that the role Sparta played was not as important as our sources suggest. Rather, my point is that what we know of life in Sparta during the classical period is a reflection of what others, often in much later periods, thought, and so does not necessarily align with reality or how the Spartans conceived of themselves.

After the painful period following Philip II of Macedon’s takeover of Sparta in 338-337 BCE, the Roman era (31 BCE-396 CE) demonstrates an obsession with recapturing and reperforming the glory of Sparta’s mythical classical past. It was fetishised and mythologised, with no apologies. In an attempt to recreate the ‘Lycurgan’ agoge, or system of education, ritual flogging ceremonies were re-enacted in the sanctuary of Artemis Ortheia, by the river Eurotas, now with the addition of an amphitheatre for Roman viewers. Classical Sparta’s perceived civil and military values were promoted as moral standards for Romans to follow. Pausanias describes a city thick with religious monuments, sites of hero-cult, and statues to generals and lawmakers. His meticulous narrative of his travels around Lakonia, taking up most of his third book of The Description of Greece, leaves us with a sense of how thickly layered time, memory and landscape were, and how this sense of a mythic past was cultivated in Roman Sparta.

Much of the reason for Sparta’s flourishing can be attributed to her inhabitants’ reckless but lucky decision to support Octavian, soon to become Emperor Augustus, in the Battle of Actium (31 BCE). This led to their currying unique favour with Rome after his victory. We also have evidence of other famous Spartaphiles, such as the orator Cicero, spending time in the city. The positive relationship between Sparta and the Roman Empire drew many wealthy Romans to Lakonia. This is further attested by the archaeological evidence, which consists of increasingly luxurious houses and baths, as well as a new theatre, one of the largest in the Peloponnese. More than 137 Roman and Late Antique mosaics have been excavated; they would have decorated the atriums and dining rooms of the splendid Roman mansions. The most famous among the mosaics, today on display for visitors to the modern town, depict Orpheus singing to the animals and the abduction of Europa by Zeus in bull form (still to be seen on the back of the Greek €2 coin).

The view from wealthy Roman villas in Sparta is a retrospective one, constantly caught up in fashioning the present relative to the past. In this sense, it sets a precedent for what’s to come.

The Eurotas valley is the perfect blank canvas upon which educated Europeans could project their fantasies

The next iteration of Sparta adds a layer of medieval Western history to a landscape littered with the memory of an ancient past. Nearly a millennium after Sparta’s days of Roman glory, in the 13th century CE, the settlement is moved from the Eurotas valley to one of the peaks that make up the foothills of the Taygetus mountains, named Mystras (or Myzithras). This is at the behest of its Frankish conqueror, William de Villehardouin, looking for a more fortified spot, which Mystras, perched like an eagle’s nest upon its craggy peak, absolutely was.

Yet this did not keep the Frankish stronghold, with its bird’s-eye view of the Vale of Sparta, safe from the Byzantines, who captured the castle in 1262. Mystras under Byzantine rule transformed into a cultural capital, built up with stunning churches and monasteries overlooking the valley, towards the sunrise over the Parnon mountains in the east. It was the home of Princess Isabella of Villehardouin, whose life later became the inspiration for the Greek writer Angelos Terzakis’s novel Princess Isabeau (1945), as well as intellectuals and philosophers such as Gemistus Plethon, widely hailed as the ‘second Plato’. In the last two centuries before Mystras fell to the Ottomans in 1460, the Byzantine dynasty known as the Palaeologi ruled, their interests in the arts and culture strengthening Mystras’s vibrant community, which was also a thriving centre of silk production and trade, as well as the cultivation of olives, grapes and mulberries.

As the art historian Sharon Gerstel writes in her introduction to Viewing the Morea: Land and People in the Late Medieval Peloponnese (2013): ‘To revisit Mystras as it was, one needs to hear the swish of silk clothing and listen for the chatter of its intellectuals, who once populated the city’s libraries and court.’ The Pantanassa Monastery (founded in 1428), filled with exquisite wall-paintings and adorned with a mixture of Byzantine and Gothic elements, might be considered the artistic chef-d’oeuvre of the period, its dizzying view over the Eurotas valley today as unparalleled as it was then.

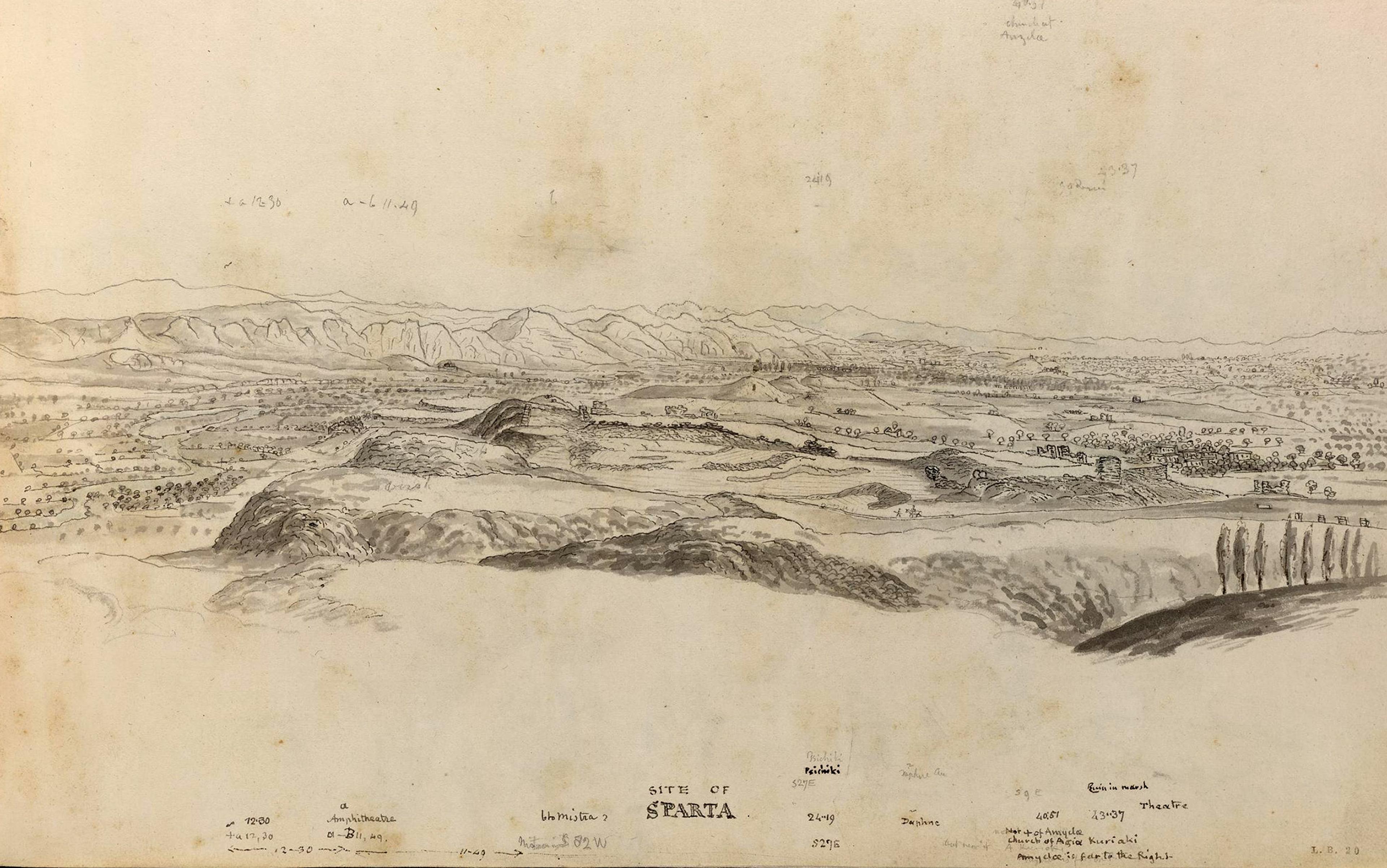

Fast-forward four centuries, and Lakonia is a land of wilderness and ruin under Ottoman rule. The Eurotas valley is the perfect blank canvas upon which educated Europeans, driven by a desire to put themselves in contact with the mythic past, could project their fantasies. In this period, landscape becomes a locus for the generation of new mythologies about Sparta, steeped in Romantic nostalgia and facilitated by the fact that the ruined remains of the city did not live up to its legendary reputation. The stories of European travellers revel in the absence of a past that is so desperately sought.

In 1754, Julien-David Le Roy, a French architect and archaeologist, undertook the perilous journey to Greece, then still a province of the Ottoman Empire, to document ‘the ruins of the most beautiful monuments in Greece’. He wrote: ‘Sparta – so celebrated for the laws established by Lycurgus and for the courage of its inhabitants – is now so ruinous, with so few buildings left there, that we feel no necessity to write the history of its former state.’ He captured the sentiment of most who came to Sparta: simultaneously overcome by the beauty of the natural environment and woefully disappointed at the state of its ruins. In the end, it was the Taygetus mountains, the Eurotas river, and the fertile valley of olive and orange trees that became the focus of their descriptive ecstasy.

In Rambles and Studies in Greece (1876), the Irish classicist J P Mahaffy praises the valley of Sparta as ‘the richest and most fertile in Peloponnesus’, its ‘undulating hills and slopes, all now covered with vineyards, orange and lemon orchards, and comfortable homesteads or villages’. He extols the ‘brilliant serrated crest of Taygetus, glittering with its snow in the sunshine’ and describes in vivid detail how:

Straight before me, so close that it almost seemed within reach of voice, the giant Taygetus, which rises straight from the plain, stood up into the sky, its black and purple gradually brightening into crimson, and the cold blue-white of its snow warming into rose. There was a great feeling of peace and silence, and yet a vast diffusion of sound.

Mahaffy’s reverence for the mountain, the unfurling of the day through the shifting of colours on its facade, the moment of stillness that it evokes, verges on the religious. This close attention to natural beauty, and intimate description of the effect of Sparta’s nature, is captured also by the French traveller Edmond About (1828-85), who focuses on the pastoral and idyllic aspects of the valley:

Thick matted grass formed everywhere carpets at the feet of the oaks and wild olive-trees; golden broom and tall heather, as high as shrubs, entwined themselves in confusion with lentisks and arbutus – a thousand strong perfumes, escaped from the soil, or exhaled from the foliage, or brought from afar by the breeze, combined to intoxicate us.

Modern Sparta did not exist until 1834, when a decree of the king of Greece, Otto von Wittelsbach, refounded a new town on the site of the ancient city. The rebuilding of Sparta aligned with the wishes of those populating the nearby village of Mystras. They wanted to connect the newborn town with its legendary past, a particularly important endeavour in the aftermath of Greece’s independence from the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the modern Greek state. This was the first time since the 13th century CE that the city of Sparta proper was inhabited.

Today, Sparta remains a modest but bustling town of Lakonia. Nestled in a lush green valley of orange and olive trees, Sparta is forever flanked by the transcendent Taygetus mountains to the west and the silver stream of the Eurotas to the east. Stroll through its streets, as I have done so many times, and you will see ancient monuments among new apartment buildings. The main street, Konstantinos Palaiologos, named after the Palaeologi of Mystra, leads to the public stadium where the town’s residents gather in the evenings to enjoy the fresh air. In front of the stadium stands a larger-than-life bronze statue of King Leonidas, perfectly positioned for touristic photo-ops. Archaeologically inclined visitors might catch, from the corner of their eye, the faded sign that points in the direction of ancient Sparta. And, in the central square, dominated by the neoclassical demarcheion, or mayor’s office, the next generations of Spartans drink their coffees, exchange news, smile, laugh, and carry on, while below their feet the palimpsest of Sparta rests.