In December 1968, the ecologist and biologist Garrett Hardin had an essay published in the journal Science called ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. His proposition was simple and unsparing: humans, when left to their own devices, compete with one another for resources until the resources run out. ‘Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest,’ he wrote. ‘Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.’ Hardin’s argument made intuitive sense, and provided a temptingly simple explanation for catastrophes of all kinds – traffic jams, dirty public toilets, species extinction. His essay, widely read and accepted, would become one of the most-cited scientific papers of all time.

Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Laureate in Economics photographed in 2011. Photo by Raveendran/AFP/Getty.

Even before Hardin’s ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ was published, however, the young political scientist Elinor Ostrom had proven him wrong. While Hardin speculated that the tragedy of the commons could be avoided only through total privatisation or total government control, Ostrom had witnessed groundwater users near her native Los Angeles hammer out a system for sharing their coveted resource. Over the next several decades, as a professor at Indiana University Bloomington, she studied collaborative management systems developed by cattle herders in Switzerland, forest dwellers in Japan, and irrigators in the Philippines. These communities had found ways of both preserving a shared resource – pasture, trees, water – and providing their members with a living. Some had been deftly avoiding the tragedy of the commons for centuries; Ostrom was simply one of the first scientists to pay close attention to their traditions, and analyse how and why they worked.

The features of successful systems, Ostrom and her colleagues found, include clear boundaries (the ‘community’ doing the managing must be well-defined); reliable monitoring of the shared resource; a reasonable balance of costs and benefits for participants; a predictable process for the fast and fair resolution of conflicts; an escalating series of punishments for cheaters; and good relationships between the community and other layers of authority, from household heads to international institutions.

A parliamentary study tour of the conservancies in 2005. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

When it came to humans and their appetites, Hardin assumed that all was predestined. Ostrom showed that all was possible, but nothing was guaranteed. ‘We are neither trapped in inexorable tragedies nor free of moral responsibility,’ she told an audience of fellow political scientists in 1997.

What Hardin had portrayed as a tragedy was, in fact, more like a comedy. While its human participants might be foolish or mistaken, they are rarely evil, and while some choices lead to disaster, others lead to happier outcomes. The story is far less predictable than Hardin thought, and its twists and turns can lead to uncomfortable places. But in those surprises lie the possibilities that Hardin never saw.

You might think that scientists, and the public, would eagerly trade Hardin’s dark speculations about human nature for Ostrom’s sunnier findings about our capabilities. But as I learned while researching and writing my book Beloved Beasts (2021), a history of the modern conservation movement, Ostrom’s conclusions have faced stubborn resistance. During the early years of her career, colleagues criticised her for spending too much time studying the differences among systems and too little time looking for a unifying theory. ‘When someone told you that your work was “too complex”, that was meant as an insult,’ she recalled.

Ostrom insisted that complexity was as important to social science as it was to ecology, and that institutional diversity needed to be protected along with biological diversity. ‘I still get asked, “What is the way of doing something?” There are many, many ways of doing things that work in different environments,’ she told an audience in Nepal in 2010. ‘We have got to get to the point that we can understand complexity, and harness it, and not reject it.’

Her research gained global prominence in 2009, when, aged 76, Ostrom became the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. But for a variety of reasons – perhaps because she was a woman in a male-dominated field, or perhaps because her sophisticated work didn’t lend itself to a catchy name – her carefully collected data hasn’t dislodged Hardin’s metaphor from the public imagination.

When Ostrom died in 2012, she was celebrated by her colleagues for her pioneering work, her plainspoken humility, and her steady resistance to what she called ‘panaceas’. She knew from experience how corrosive simple stories could be. Hardin, for his part, seemed bent on making his own ideas as repugnant as possible. Among his proposed solutions to the tragedy of the commons was coercive population control: ‘Freedom to breed is intolerable,’ he wrote in his 1968 essay, and should be countered with ‘mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon’. He feared not only runaway human population growth but the runaway growth of certain populations. What if, he asked in his essay, a religion, race or class ‘adopts overbreeding as a policy to secure its own aggrandisement’? Several years after the publication of ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, he discouraged the provision of food aid to poorer countries: ‘The less provident and less able will multiply at the expense of the abler and more provident, bringing eventual ruin upon all who share in the commons,’ he predicted. He compared wealthy nations to lifeboats that couldn’t accept more passengers without sinking.

Hardin compared wealthy nations to lifeboats that couldn’t accept more passengers without sinking.

In his later years, Hardin’s racism became more explicit. ‘My position is that this idea of a multiethnic society is a disaster,’ he told an interviewer in 1997. ‘A multiethnic society is insanity. I think we should restrict immigration for that reason.’ Hardin died in 2003, but the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center, alert to the longevity of his ideas, maintains his profile in its ‘extremist files’ and classifies him as a white nationalist.

Still, many of those who abhor Hardin’s racist ideas – or would if they were aware of them – are seduced by the simplicity of his tragedy. If academic citation indexes are any guide, the tragedy of the commons remains far better known to scholars than any of Ostrom’s findings. It continues to be taught, uncritically, to high-school students in environmental science courses. It’s used as a justification by those who support severe restrictions on human immigration and reproduction. Even more frequently, it’s casually invoked as an explanation for human failures: even the eminent biologist E O Wilson, in his book Half-Earth (2016), describes the weakness of international climate-change agreements and the ongoing depletion of ocean resources as tragedies of the commons, without making clear that such tragedies can be averted.

Despite the evidence gathered by Ostrom and her colleagues, it seems, many are still all too willing to believe the worst of their fellow humans – to the detriment of conservation efforts worldwide. Like Hardin, many conservationists assume that humans can only be destructive, not constructive, and that meaningful conservation can be achieved only through total privatisation or total government control. Those assumptions, whether conscious or unconscious, close off an entire universe of alternatives.

While Ostrom’s ideas are not yet familiar maxims, they haven’t been ignored. In southern Africa in the 1980s, some conservationists recognised that parks and reserves, many created by colonial governments, had divided subsistence hunters and farmers from much of the wildlife that had long sustained them – and which, in some cases, they’d managed as a commons for generations. The resulting lack of local support meant that even the best-patrolled park boundaries were vulnerable to incursions by human neighbours, people unlikely to tolerate – much less protect – the large, sometimes troublesome species that ranged beyond even the largest reserves.

A local warden at the Wuparo Conservancy in Namibia. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

In response, new initiatives attempted to redistribute the burdens and benefits of conservation: the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) project in Zimbabwe directed revenue from hunting and tourism on communal lands to district councils, incentivising those councils and their communities to control illegal hunting. In neighbouring Zambia, the Administrative Management Design (ADMADE) programme trained local people as wildlife rangers, then transferred some wildlife management responsibilities, and benefits, from the national government to community boards. These and similar efforts became known as community-based conservation.

In 1987, when the South African conservationist Garth Owen-Smith attended a conference on community-based conservation in Zimbabwe, a comment by Harry Chabwela, the director of Zambia’s national parks, left a lasting impression. ‘At this conference we have talked a lot about giving local people this and giving them that, but what has been forgotten is that they also want power,’ Chabwela said. ‘They want a say over the resources that affect their lives. That is more important than money.’

Owen-Smith had already spent years living in Namibia, which was controlled by South Africa and known as South West Africa. When severe drought and an epidemic of illegal hunting threatened livelihoods and wildlife in the territory’s northwestern desert in the early 1980s, Owen-Smith had supported the creation of a system of community game guards. The unarmed guards – many of whom were hunters themselves – were so effective at tracking illegal hunters that, after a few years, the killing of elephants and rhinos in the region stopped completely. Antelope numbers improved so much that Owen-Smith was able to persuade the national conservation department to reopen limited game hunting in the area – a development much appreciated by locals.

Local wardens conduct a game count in Caprivi, Northeastern Namibia. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

Chabwela’s comment about power motivated Owen-Smith to think bigger. When he returned home, he and his partner Margaret Jacobsohn began to talk with community leaders and members about ways of restoring some local authority over wildlife. After Namibia won independence from South Africa in 1990, the new government recruited Jacobsohn and Owen-Smith to survey rural attitudes toward conservation, and the survey confirmed what the two had by then been hearing for years: most people didn’t want the occasionally dangerous species they lived with to be killed or removed – but they did, as Chabwela had suggested, want a say in their management. In 1996, the Namibian National Assembly passed a law that allowed groups of people living on communal land to establish institutions called conservancies. Conservancies would be governed by elected committees, and all members would share the benefits of any tourism or commercial hunting within conservancy boundaries.

Trophy hunters are sometimes directed toward lions and elephants who have become aggressive toward people.

The first conservancies on communal land were formalised in 1998, and there are now more than 80 of them in Namibia. They cover more than 40 million acres of land, and stretch from the northwestern desert to the humid, densely populated Zambezi Region in the northeast. They earn revenue from lodges, campgrounds and guide services, both as partners in joint ventures and as solo operators. They participate in annual surveys of game and wildlife populations and, in cooperation with the national conservation ministry, set quotas for both subsistence and commercial hunting within their boundaries. They employ their own game guards, who are currently fending off a continent-wide wave of rhino poaching driven by Asian demand for powdered rhino horn (a discredited traditional medicine). And, every year, the members of each conservancy assemble to call their governing committees to account.

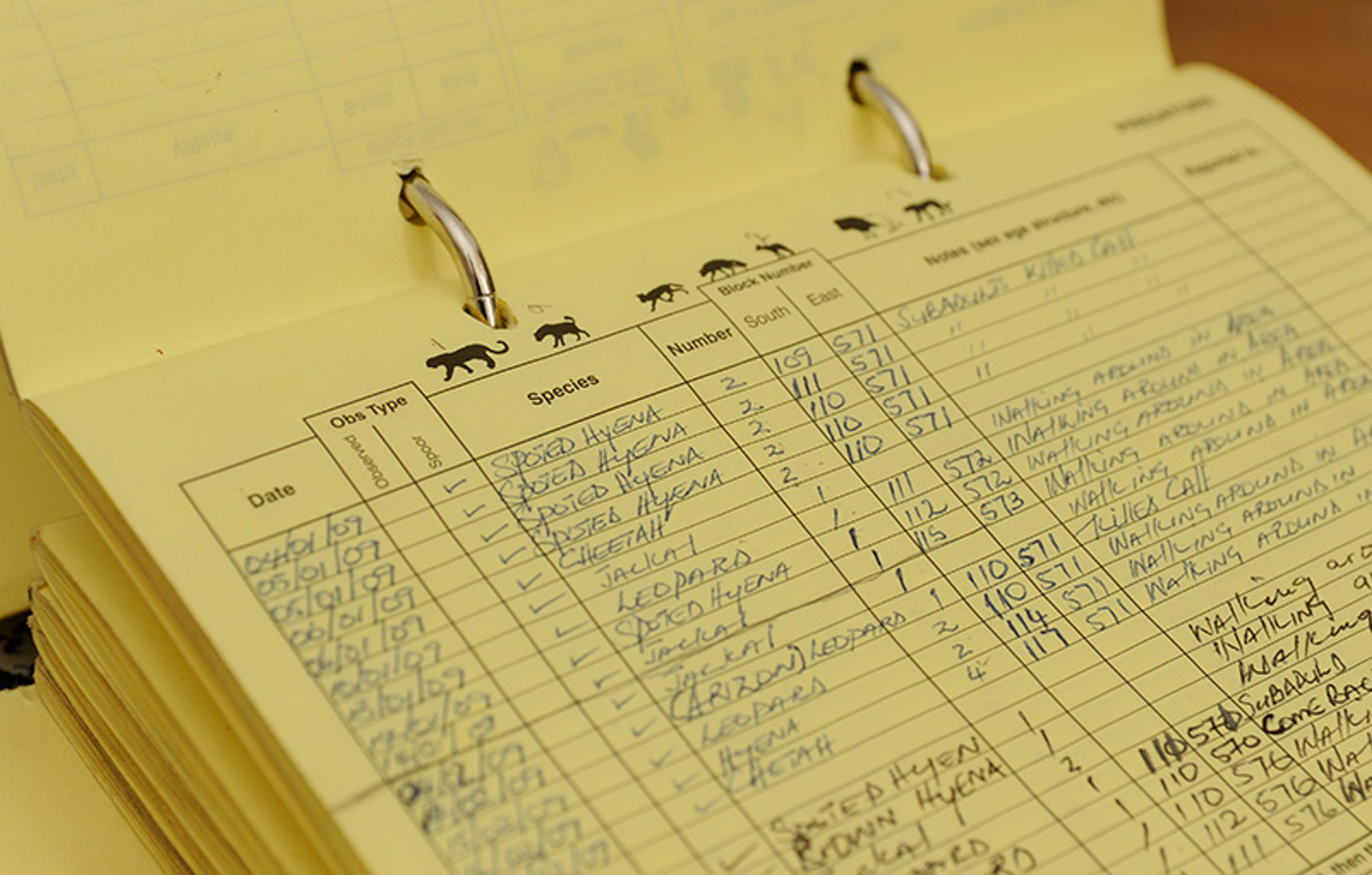

Detailed recods are made of local wildlife. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

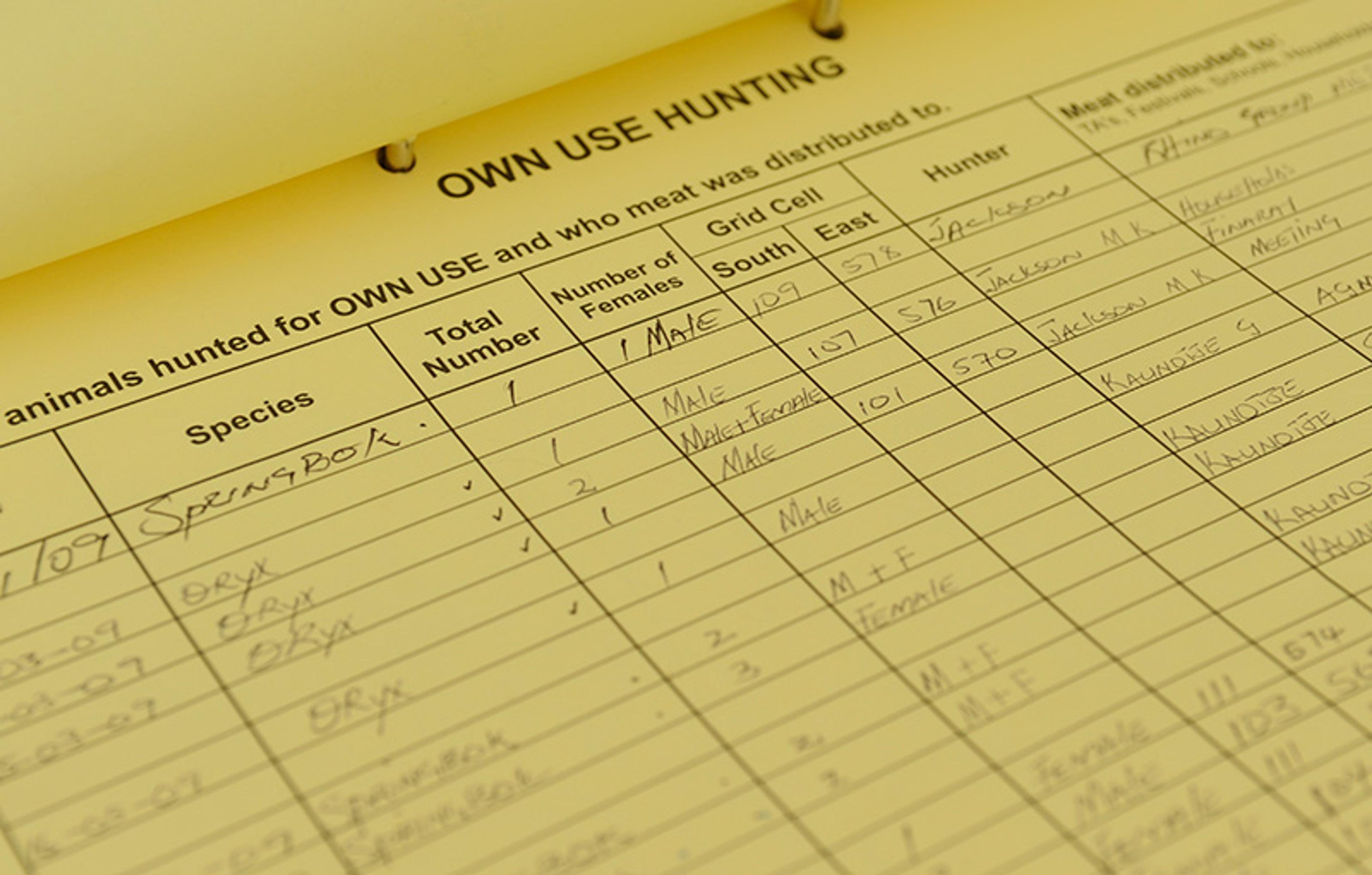

Local hunting quotas are agreed upon. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

In August 2019, I attended the general meeting of Orupembe Conservancy, held in an open-air pavilion on the outskirts of Onjuva, a tiny town hundreds of miles from the nearest gas station, and even further from a paved road. Most of the people at the meeting were semi-nomadic herders, many of whom had travelled long distances from even more isolated corners of the conservancy. (I was present thanks to the expert off-road driving skills of the guide Edison Kasupi, who grew up in nearby Purros Conservancy.) When the Onjuva committee called the meeting to order, there were 95 people seated inside the pavilion, about half of the conservancy members and just enough for a quorum. The chairman Henry Tjambiru commented that the current drought had forced many people to take their herds further afield, preventing them from attending.

Orupembe Conservancy has several sources of income, all relatively modest: a campsite, a small lodge that it co-owns with two other conservancies, and contracts with a handful of hunting guides. (Some conservancies have very little income, and fund their operations with donations from international conservation groups; others, such as the neighbouring Marienfluss Conservancy, have joint venture agreements with upscale lodges that can net more than $100,000 a year in salaries and fees.)

After a review of the year’s earnings, the committee distributed a list of local species and the current hunting quotas for each. Because the drought had worsened since the quotas were set, conservancy members had voluntarily left most of them unfilled. While wildlife surveys earlier in the year had suggested that 75 oryx could be killed without harming the population, for example, only three had been shot so far. The meat from two of those was currently boiling in a nearby row of pots, about to be served for lunch.

The meeting, which lasted several hours, was disrupted by procedural inefficiencies, lively sideline arguments and, at one point, an accusation of petty corruption. But as the sun sank and the meeting came to a ragged end, I realised with surprise that I was exhilarated. During an exceptionally difficult year, these conservancy members had taken the trouble to travel to the meeting, consider the long-term future of other species, and recommit themselves to ensuring it.

In reviving the commons, the Namibian conservancies have revived the relationships between people and wildlife – and the results, as Ostrom would be unsurprised to learn, are complex. Where parks and reserves separate land into clearly defined categories, community-based conservation proposes that land can be simultaneously protected and utilised – through the cooperative efforts of the people who live on it. It’s a profound challenge to Hardin’s assumptions, and while some of its outcomes are easy to applaud – the recovery of elephants and rhinos, the arrival of new jobs – others make outsiders squirm.

A vulnerable rhino is relocated. Photo courtesy NACSO/WWF Namibia

John Kasaona, who grew up in northwestern Namibia and, as a boy, watched Owen-Smith and his father set out on game-guard patrols, is now the executive director of Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation, a nonprofit organisation that provides technical support to the conservancies. When he travels overseas to talk about the accomplishments of the Namibian conservancy system, he mentions only briefly, if at all, that its success depends in part on income from trophy hunters – tourists who pay for the privilege of shooting an animal for sport, and who in some cases keep hides or horns for display. For many conservancies, trophy hunting is not only a source of income but a tool for preserving the peace between humans and other species, since trophy hunters are sometimes directed toward individual lions or elephants who have become aggressive toward people.

Kasaona is well aware of the images that trophy hunting conjures in his listeners’ minds: Theodore Roosevelt standing next to a fallen elephant, dwarfed by the carcass and its upturned tusks; Eric Trump grinning as he hefts the limp body of a leopard, his brother Don Jr beside him; the Zimbabwean lion named Cecil, whose illegal killing by a dentist from Minnesota during a guided hunt in 2015 caused a global outcry. For some in North America and Europe, trophy hunting in Africa has come to symbolise human sins against other species.

In 2017, after Kasaona spoke at a Smithsonian Institution conference in Washington, DC, a young woman stood to speak at the audience microphone. ‘I think that some pieces were missing from the presentation,’ she began. Kasaona had not shown images of the animals slain by trophy hunters, she said. He had neglected to mention that the lion or elephant spotted by a visiting family on safari might be killed the next day. Kasaona, at the podium, acknowledged the international controversy over trophy hunting, but said that regulated commercial hunts remained an important source of revenue for the Namibian conservancies. There was more to say, but the session was over, and any further discussion was washed away by chatter.

Even in the darkest times, Ostrom’s work reminds us that the future is unpredictable and full of opportunity.

More than two years later, I met up with Kasaona in the town of Swakopmund, about halfway down the Namibian coast. We talked over generous plates of springbok curry at the colonial-era Hansa Hotel, where German is spoken more frequently than English, and both are far more common than any of Namibia’s 20-plus Indigenous languages and dialects.

I asked Kasaona to finish answering his questioner at the Smithsonian conference. ‘People say: “I don’t like what they’re doing to animals,” but most of them wouldn’t want to live next to a lion that could harm their family,’ he said. The majority of tourists who hunt for sport in Namibia pursue more common species such as springbok, whose hunting is permitted through the conservancy quota system. In the case of globally threatened species, the number of animals (if any) that can be shot each year is set by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). In 2004, the parties to the convention approved applications by Namibia and South Africa to allow limited hunting of black rhinos, determining that the population had recovered to the point that five male rhinos could be shot in each country each year. In Namibia, the national conservation ministry chooses which rhinos will be hunted – usually older animals that have become aggressive or territorial – and issues permits for the hunts. The permit fee is deposited in a national conservation trust fund, and in one recent case a hunter paid $400,000 to shoot a single male rhino, far more than most conservancies earn in a year.

The trophy-hunting system in Namibia isn’t perfect, Kasaona acknowledges – there are cases where hunters have killed the wrong animal – but over the long term, he said, it benefits both the conservancies and the species in question by reducing conflicts between people and wildlife. When international conservation groups promise to regulate and censure trophy hunting out of existence, Kasaona hears what he calls ‘another kind of colonisation’ – a violation of the local authority that he and others have spent decades building up, and a threat to the revenue it depends on. ‘What do they say to the people whose livelihood depends on what they are trying to ban?’ he says.

Global restrictions on trophy hunting, Kasaona argues, are a simplistic response to a complex situation – what Ostrom might call a panacea. Not all countries are alike; not all conservancies are alike; not all conservancy members are alike; not even all trophy hunters are alike. And a few individual lions and elephants are far more dangerous than others, as those who have lost loved ones and livelihoods to rogue animals can attest.

While those viral images of trophy hunters with carcasses might all seem to say the same thing, they don’t. Some, surely, are symbols of corruption or needless violence. But, in the best cases, they’re examples of sustainable utilisation: colonial nostalgia, harnessed by the formerly colonised to further multispecies survival.

Ostrom’s principles of commons management now underlie not only the Namibian conservancy system but hundreds of similar efforts throughout the world. Many have revived and adapted conservation practices developed centuries ago, developing new rules suited to current circumstances. Their creators cooperate in the management of coral reefs in Fiji, highland forests in Cameroon, fisheries in Bangladesh, oyster farms in Brazil, community gardens in Germany, elephants in Cambodia, and wetlands in Madagascar. They operate in thinly populated deserts, crowded river valleys, and abandoned urban spaces.

While conservation almost always carries at least some short-term costs, researchers have found that many community-based conservation projects reduce those costs and, over time, deliver significant benefits to their human participants, tangible and intangible alike. And while community-based conservation began as a reaction to top-down conservation strategies, it can operate in parallel with large parks and reserves – and even foster their creation. In northwestern Namibia, two neighbouring conservancies have proposed to establish a ‘people’s park’ where livestock would be excluded and tourist numbers would be limited by a permit system, allowing lions and other large predators to more easily avoid conflicts with humans. Should the national legislature approve the conservancies’ proposal, the region could serve as a core habitat from which large carnivores can range in relative safety – since the region’s biological diversity is now protected not only by law, but by supportive human neighbours.

Community-based conservation can’t solve everything, and it doesn’t always succeed in protecting the commons. In many cases, national governments don’t recognise the longstanding land claims of Indigenous and other rural communities, creating uncertainty that interferes with community efforts to manage for the long term. Even well-established systems are vulnerable to internal conflict, and to external pressures ranging from drought to war to global market forces. As Ostrom often reminded her audiences, any strategy can succeed or fail. Community-based conservation is distinctive because many societies have only begun to understand – or remember – its potential. ‘What we have ignored is what citizens can do,’ she said.

At Indiana, Ostrom and her husband Vincent, also a political scientist, founded the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, affectionately known as ‘The Workshop’ to the researchers who continue to gather there. Current students of commons management struggle, as Ostrom did, with the difficulty of managing large-scale resource problems such as air pollution at the community level. They wrestle with the implications of her findings for the digital landscape, where the veneration of open access often collides with Ostrom’s definition of the commons as a boundaried, regulated space. And despite what one researcher in 2011 dubbed ‘Ostrom’s Law’ – that whatever works in practice can work in theory – even Ostrom’s admirers sometimes echo her earliest critics, lamenting that the field lacks an overarching theory.

The challenge of understanding the complexity of all species continues, as does the challenge of seeing possibility in what so often looks like a collective tragedy. But even in the darkest times, Ostrom’s work can remind us that the future is deliciously unpredictable, and full of opportunities for us to stumble away from the edge.

This original essay draws on the book ‘Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction’ (2021) by Michelle Nijhuis, published by W W Norton & Co.