The state of sex education in the United States is dismal. Shaped by divergent state policies and local school board decisions, programmes are uneven in their content and coverage. There is confusion about what is being taught where. Most programmes are limited in scope, some are even harmful. Proponents of comprehensive sexuality education urge the teaching of reproductive development, contraception and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) but, far from these goals, they have fought and failed to ensure the bare minimum standard in more than half of the states: that lessons in sex education be medically accurate. Meanwhile, comprehensive programmes are attacked as too revealing and immoral by supporters of abstinence-only sex education, recently re-branded as ‘sexual risk avoidance education’, which tends to dissuade students from engaging in any sexual activity at all. Both factions argue that the country will continue to fail its youth unless schools embrace their version of sex education.

At the national level, the debate over sex education has generally followed culture war divides, with liberals supporting comprehensive sexuality education, and conservatives leading calls for sexual risk avoidance education. Long aligned with the latter has been white conservative Protestantism, the religious group most vocal in public debates about sex education since the late 1960s. But it would be wrong to think of the sex education debate as simply ‘religious versus secular’. In fact, religions are not one-sided on this issue, and cannot be separated from these discussions. A look at the history of sex education in the US shows that religions – especially Protestant denominations – have deeply influenced many aspects of sex education, both progressive and conservative. This is not surprising given the symbolic value of sexuality, as well as the transmission of moral values through sex education, both of which make it a key battleground in the culture wars. Sex education is attached to the control of young bodies through lessons about sexual diseases, reproduction and romantic pairings, as well as the control of young minds through the classroom. In formative ways, Christian involvement in the history of sex education laid the groundwork for both sides of the debate today.

Sex education began with 19th-century Protestant anti-prostitution reformers. These reformers led the ‘social purity movement’ (‘social’ was then a euphemism for ‘sexual’). They paired their primary work of stamping out red-light districts with educational lectures about the physical and moral dangers of sex outside marriage. Social purity overlapped with other female-dominated reforms such as the temperance movement; alcohol and prostitutes were twin evils that lured men away from their Christian households. Social purity advocates such as Frances Willard, the leader of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, preached against the sexual standard that condoned men visiting prostitutes, while those such as John Harvey Kellogg, the inventor of cornflakes, emphasised premarital abstinence and marital monogamy as essential to a healthy Christian lifestyle. Ironically, social purity reformers supported obscenity laws to protect youth against lewd sexual publications, even as they challenged the prevailing ‘conspiracy of silence’ around public discussions of sexuality.

Whereas sex education was secondary to anti-prostitution reforms, it became a primary focus of doctors who began advocating for ‘social hygiene’ (ie, sexual hygiene) in the early 20th century. The father of social hygiene – and the founder of US sex education – was a man named Prince Albert Morrow, a Kentucky-born dermatologist inspired by the advanced studies of venereal diseases in France. In the US, he promoted social hygiene education in order to protect ‘innocent’ wives and offspring from the ravages of syphilis and gonorrhoea introduced into the family by husbands and fathers. He showed a flair for publicity by disseminating stomach-turning images of syphilitic children suffering from blindness and skin deformities. Morrow soon began to organise his campaign among fellow doctors, but progress was slow. Despite some being passionate about fighting venereal disease, many were nervous about treating syphilis and gonorrhoea since these diseases were popularly seen as fit punishments for sexual sins. Easing symptoms supposedly encouraged patients to continue their sinful behaviour – not a position doctors were keen on defending.

So Morrow moved outside his professional scientific circle and engaged with Protestant social purity reformers as well. They had already developed publicly acceptable Christian rhetoric for talking about sexuality in a time when obscenity laws stifled other public discussions. Those who accepted Morrow’s invitation to join scientific professionals in creating the sex education movement made up the more progressive branch of purity reform. Influenced by liberal Protestantism’s embrace of scientific authority to reveal God’s truths about creation, they sought to cooperate across religious and secular divisions as part of their Christian mission to mitigate social problems. Now Morrow’s movement took off in earnest.

Morrow had learned a lesson that recurs throughout the history of sex education: adding religious frameworks and spokespeople into medical campaigns is necessary for success. Facts and data are often not enough to convince the US public to take scientific lessons about sex seriously; religious persuasion is needed too. So, since the early 20th century, the sex education movement has treated Christianity as a fount of ample resources: live audiences (church attendees and auxiliary networks), free advertising (religious pulpits and publications), reputable leadership to guide and promote sensitive campaigns (ministers and other respected church people), an ethical system to motivate people to ‘behave’, and ideologies that safeguarded the topic from censorship by connecting it to well-accepted ideas of love, family and Christian respectability. Morrow’s work helped to create a coalition between social hygiene and social purity or, as he would later put it, between ‘the medical man and the moralist’. This eventually led to the creation in 1914 of the American Social Hygiene Association (now the American Sexual Health Association), an organisation that would guide the national sex education movement for decades to come.

The coalition that Morrow helped to create was particularly significant at a time of scientific professionalisation. Confidence was high in science, especially medicine, to solve society’s problems. As scientific authority had become largely independent of religious authority by the early 20th century, some physicians accused conservative Christian reformers of spreading inaccurate medical information in their religious enthusiasm to curb vices. Doctors feared that religious approaches would always advocate for conversion and prayer over scientific education and medical intervention, even though liberal Protestant purity reformers who joined them also eschewed these more conservative evangelical reform methods.

Most early sex educators supported beliefs related to social Darwinism

For their part, purity reformers had reasons to distrust doctors, as some had stymied anti-prostitution reforms with their advocacy for medical regulation of prostitution, which would have amounted to legalising it – anathema to those who wanted its abolition. But where there was overlap, there was success. Christian doctors and leaders such as Morrow advocated for a balance of religion and medicine within both groups, and helped to bridge tensions. Both agreed on the connection between prostitution, STIs and weak morals. They decided on sex education for children as the best way to address these problems so that boys would learn the dangers of visiting prostitutes, and girls would choose husbands who upheld a higher sexual standard. Early sex-education leaders made careful negotiations to keep a balance of approaches.

Elevating religious concerns also provided a reason to keep the sex education movement separate from the birth control movement. Endorsing birth control would have ostracised prominent Catholic sex educators such as John Montgomery Cooper. An anthropologist and priest, Cooper was well aware of the Roman Catholic position against artificial birth control methods but saw great value in sex education to discourage sin, strengthen character, and support reproduction within nuclear families. The decision by the American Social Hygiene Association to remain neutral on birth control – viewed as a more radical, feminist cause – further protected the movement from censorship and public outcry in its early years. At a time before most public schools were ready to incorporate lessons about sexuality, religious groups provided direct access to parents who would help to decide whether to let sex education into schools; they also offered experimental locations for developing and trying out these programmes.

The movement’s goals aligned with progressive education trends that sought to use public education to strengthen moral character and, ultimately, the nation. Sex educators of both religious and medical varieties shared concern for growing ‘problems of the cities’, which was often code for white people’s fears about an influx of immigrants and Black people to urban areas, a trend they believed fuelled vice and spread diseases. Like many progressive white elites of the time, most early sex educators supported beliefs related to social Darwinism, using middle-class Anglo-Saxons as a common benchmark for depicting ideals within sexual hygiene campaigns. Many sex educators came to support popular aspects of so-called ‘positive eugenics’, including the idea that keeping sexuality contained within a ‘well-matched’ marriage (ie, same race, class, religion, etc) would advance each race, although some sex educators notably denounced the eugenics movement for promoting sterilisation and other ‘negative eugenic’ measures.

After early experiments with public school sex education in Chicago, sex educators temporarily shifted to the immediate challenge of educating young soldiers about sexual temptations during the First World War. The military had a bad reputation for letting soldiers sow their wild oats; in response to parental uproar, the US government enlisted sex educators of the American Social Hygiene Association and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) to build a military sex-education programme. The sex educators focused on the moral side of sex, while military doctors lectured on STI symptoms and how to use a prophylactic kit when moral restraint failed. YMCA sex educators connected these lectures to their physical programmes to keep men morally, mentally and physically fit, with the goal of preventing men from visiting prostitutes or engaging in the largely unspoken option of same-sex intercourse.

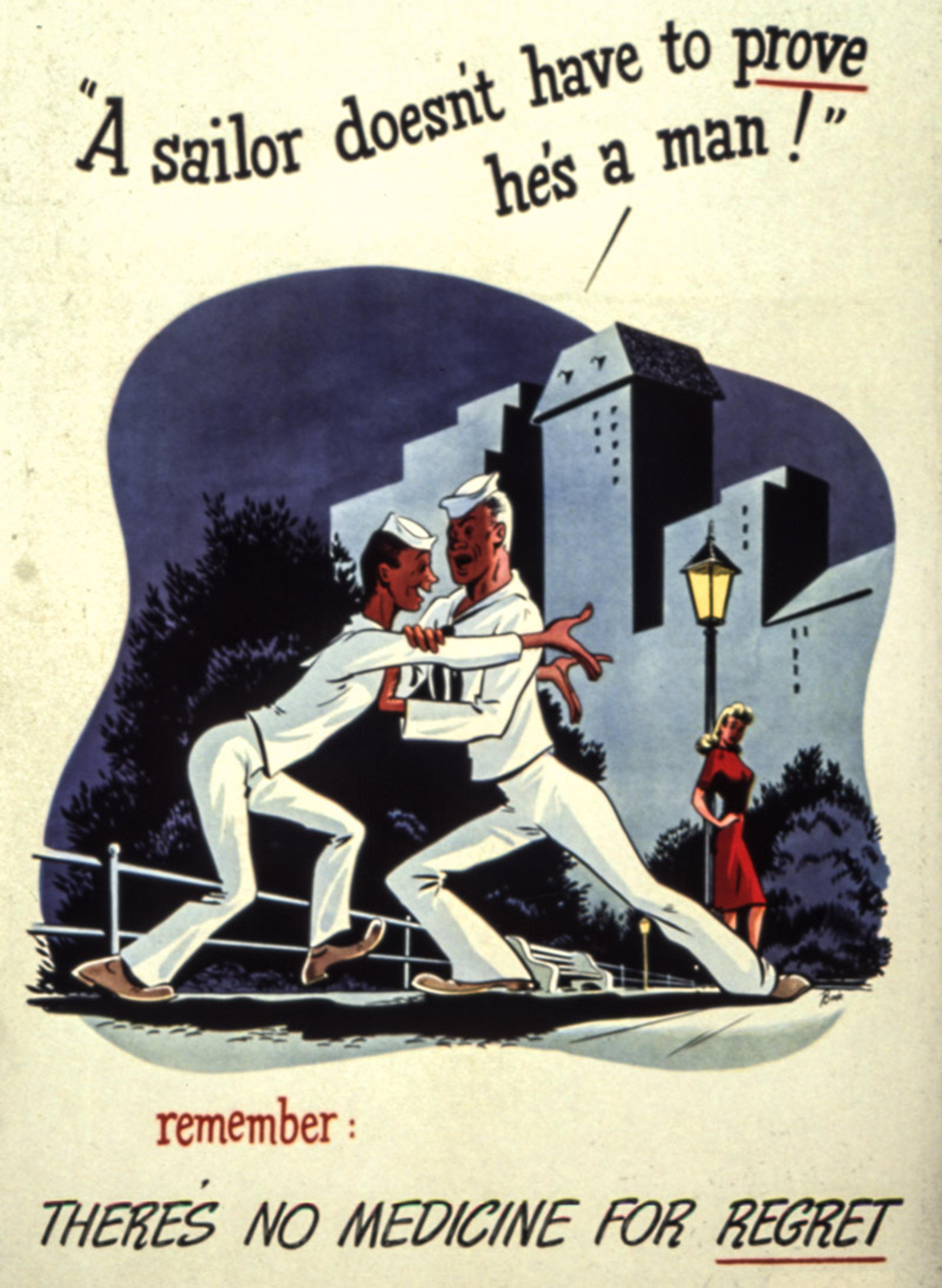

A US Navy poster from 1942 warning of the perils of venereal disease. Courtesy NIH Digital Collections

YMCA lecturers such as James Naismith, the inventor of basketball and sex educator to the American Expeditionary Forces, used Christianity as a powerful motivator to encourage soldiers to stay morally and physically ‘clean’ while overseas. Along with lectures and counselling sessions, Naismith considered sports a wholesome way to expel sexual energy and distract soldiers from sexual temptations. Chaplains, mostly Protestant, supported YMCA sex educators in urging soldiers to strengthen their Christian character and stay away from prostitutes. Moral education about sex was one piece of a larger ‘American plan’ to stop the spread of STIs, which included policing red-light districts. Incarceration and forced medical examinations followed racist, classist and sexist assumptions, as they targeted women deemed ‘problematic’ by those in power.

Religious institutions convinced parents that sex education was not smut and could serve godly goals

After the war, attention shifted back home. Religious leaders within the American Social Hygiene Association steered away from STI education and toward family life education. The liberal Protestant sex educator Anna Garlin Spencer led this shift, arguing that sexuality education was intimately connected to raising morally responsible children. As a pathbreaking female minister – the first woman to be ordained in Rhode Island and a leader in social purity, suffrage and pacifism – as well as a sociology professor, Spencer believed that religious groups had an obligation to support sex education, which would strengthen the family unit as the building block of each religion and of the nation. Her argument corresponded with broader concerns about the perils facing the modern family, primarily divorce, and overlapped with social scientific trends for domestic sciences, home economics, social work and marital counselling. Family life education echoed racial and cultural ideals of the eugenics movement about the importance of finding an ‘ideal’ partner with whom to marry and reproduce. It further reflected liberal Protestant efforts to be on the cutting edge of academic trends and a desire to find common ground across religious groups, since they believed all could agree on the religious and national importance of strengthening the social institution of the family (read: the heterosexual, nuclear family).

Spencer created a partnership between the American Social Hygiene Association and the Federal Council of Churches (now the National Council of Churches), which represented many mainline Protestant denominations and provided a voice for the moderate centre of liberal Protestantism. The Federal Council of Churches committed itself to preserving ‘Judeo-Christian family life’ as the cornerstone of the nation, adding Reform Jewish and progressive Catholic sex educators to their liberal Protestant agenda. With the new focus on family life, the sex education movement used the Federal Council of Churches to reach churches and synagogues, convincing them to include family life education in their youth programmes. Religious institutions provided important testing grounds at a time when sex education was slow to catch on in school curricula, and they served as trustworthy avenues for convincing parents that sex education was not smut and could serve godly goals, paving the way for school programmes.

These religiously affiliated efforts pushed sex education forward through the mid-20th century, providing further infrastructure for the movement and making the platform more publicly acceptable. They chipped away at the conspiracy of silence and found ways of educating parents, young soldiers and some children, overcoming concerns that any discussion would incite sexual curiosity and depravity. Despite progress, the specific frameworks and decisions had consequences, shackling sex education to a certain ideal of family (as heterosexual, white, middle-class, and nuclear) and to morals (of a specifically white liberal Protestant variety). The overarching belief that the proper domain for sexuality was within monogamous, heterosexual marriages forged the sex education consensus in the first half of the 20th century. It didn’t last much longer.

These progressive coalitions and agendas brought about their own downfall, laying the groundwork for the tumultuous sex education battles of the 1960s. Progressive religion wanted to invite everyone to the table, though still on progressive and usually Protestant terms. One perennial challenge of this liberal impulse is the question of how to be inclusive of those who don’t accept the same terms of inclusiveness. Not everyone wants a spot at the table, and some exclusive worldviews feel compromised when certain groups are allowed to join the conversation on equal footing.

The Protestant brand of liberal theology that came to influence sex educators centred around the ‘new morality’, also known as situation ethics. Popularised by Joseph Fletcher, an Episcopalian professor of social ethics, it advanced the idea that to value inclusiveness and individualism meant acknowledging that morality is not the same for everyone in every situation. In place of absolute morality, the new morality advocated a Christian view of love as a common denominator to guide individuals in their unique contexts. Despite critiques that this was a slippery slope into moral bankruptcy, proponents argued that teaching individual decision-making guided by love would lead to higher standards. Fletcher advocated situation ethics for people to ‘choose like people, not submit like sheep’, suggesting that legalistic tactics produced ‘reluctant virgins and technical chastity’, with people acting as they were told to, rather than according to their own determinations.

As the new morality became the central religious framework of comprehensive sexuality education, it opened the door to discussions of previously taboo topics. Even though many comprehensive sexuality educators – including Mary Calderone, the founder of the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States – believed that sex belonged within monogamous, heterosexual marriages, the new morality opened up the possibility that any sexual act could be moral, given the right contexts and motivations. Calderone also had a personal interest in education about the naturalness of masturbation, recalling her own trauma at being forced to wear aluminium mitts as a child to prevent her from touching herself. Informed by her progressive Quaker faith, Calderone advocated for the new morality to empower individuals to follow their own conscience and to denounce judging others’ sexual behaviour, since she believed that God could speak privately to individuals and that only God could judge how people responded to those intimate messages. She viewed education about sexual topics of all varieties to be part of the search for God-given truths, as well as vital to improving public health.

In 1996, abstinence-only sex education received an enormous boost of federal funding of $50 million a year

Acknowledgement of sexual diversity was significant for those rendered invisible or deviant by traditional frameworks. It was the liberal straw that broke the camel’s back, as conservative Christians relied upon absolute morality to support their ethical foundation: some things are always wrong, regardless of reason or context, a view tied to the belief that the Bible conveys unchanging, universal truths from God. The sex education battles of the late 1960s erupted when conservative Christian groups such as Christian Crusade launched public campaigns against comprehensive sexuality education, accusing it of promoting an anything-goes, anti-God morality that would lead to sexual chaos and the downfall of Christian America. Christian Crusade’s pamphlet Is the School House the Proper Place to Teach Raw Sex? (1968) inflamed opposition to sex education as it reached households across the country.

By making sure that moral behaviour was a central concern of sex education, liberal Protestants had convinced Americans that sex education was important for raising children and building strong families. But after the 1960s, they lost control over whose morals guided the lessons. When the mainstream Judeo-Protestant consensus that had been used to justify family life education gave way to a rejection of universal morality, conservative Christians stepped in to put their morals at the centre of sex education. After spending years on defence against comprehensive sexuality education, evangelicals such as Tim LaHaye went on the offensive in the 1980s with abstinence-only education. LaHaye and his wife had reached bestseller status with their sex manual, The Act of Marriage (1976). Building on that success, he sought to prove that sex education could also be sanctified for conservative Christian purposes. Others followed, making abstinence-only education an integral part of the Christian Right’s pro-family movement and evangelical purity culture, known for its silver rings and virginity pledges.

In 1996, abstinence-only received an enormous boost of federal funding ($50 million a year), supporting the message that ‘a mutually faithful monogamous relationship in the context of marriage is the expected standard of human sexual activity.’ Christian abstinence-only campaigners worked to remove the most explicit religious language to fit their curricula within public schools. Abstinence-only federal funding has remained fairly consistent, with only a brief lull for less than a year under the Barack Obama administration, during which time a separate funding stream was made available to comprehensive sexuality education.

Even the liberal Protestant trend of embracing science as a method for revealing God’s truth came back around, as conservative Christians borrowed scientific language to argue that their version of sex education was representative of God’s will. Medically accurate sexual terminology that evangelicals had initially labelled pornographic now became part of their arsenal, within a framework of ‘Just say no.’ Abstinence-only advocates took the same statistics that comprehensive sexuality educators used to demonstrate the need for more expansive programmes, and argued the opposite: that high rates of STIs and unintended pregnancies indicated the failure of comprehensive sexuality education, therefore demonstrating the need for restrictive programmes that exclude lessons on the effectiveness of contraceptives and the diversity of sexual and gender identities.

Peer-reviewed scientific studies have largely rejected the abstinence-only rationale, demonstrating that comprehensive approaches are more effective across multiple types of measurements. While some abstinence-only programmes have proven effective on specific behavioural outcomes, scholars and some policymakers have further critiqued such programmes for medical inaccuracies and harmful messages against LGBTQI youth and students who have been sexually active, either voluntarily or involuntarily. Adding to confused public discourse over the effectiveness and ineffectiveness of programmes is a tangled mess of policies that vary dramatically across states. The politicised nature of sex education also leads to teachers and textbook creators self-censoring for fear of parental complaints or school board retaliation, much as narrow anti-evolution laws in the early 20th century had the broader effect of inclining teachers to downplay the topic.

Sex education battles form the roots of the Christian Right, and they became entangled with later developments of evangelical resistance to racial integration in their schools and an alignment with the Republican Party in the 1970s. Protests against comprehensive sexuality education provided an opportunity to use sexuality to represent other political issues, showing the symbolic potency of sexuality as a carrier for moral values. The subsequent growth of abstinence-only programmes further strengthened their pro-family platform. These developments helped the Christian Right forge its Christian nationalist ideology.

Looking back on this history prompts the question of why scientific professionals needed religion in the sex-ed movement in the first place. Besides the resources and experience that Protestant reformers brought to the table, in the words of the scientists themselves, science was not enough. Early sex educators knew that data and facts were insufficient for changing sexual behaviours. One pointed out that doctors still contracted STIs, even though they knew the most about them, so something more than information must be needed to convince and motivate people to follow sexual health guidelines.

The realisation that scientific information alone was ineffective for the goals of sex education should resonate, as there are still many cases in which the US public remains resistant to scientific findings on controversial topics. Many Americans’ resistance to the overwhelming consensus on the basics of human evolution is one case in point, and one in which Protestantism has similarly played complex roles, with liberal Protestantism championing mainstream scientific authority, conservative Protestantism developing alternative rationales for creationism, and many individual beliefs falling somewhere along the spectrum between these national talking points. Religious responses to COVID-19 have revealed some similar divisions. A 2020 study found that those who held a Christian nationalist ideology – supported mostly by politically conservative Christians who believe the Bible should be interpreted literally – were most likely to reject scientific findings about the efficacy of masking, social distancing, and vaccination while other highly religious Americans were supportive of these same measures.

If we evaluated maths classes by how many people could complete their tax forms, we’d also have cause for alarm

Religious affiliations, of course, are not the only factors influencing the public reception of scientific data and discourses. Common distrust of ‘science’ (as if it were just one thing) can stem from the overuse of scientific jargon, the nonlinear process of scientific discovery, and real scientific mistakes, including corruption of individual researchers and classist, sexist and racist projects in the past and present. However, as the history of sex education demonstrates, religions have complex influences on secular issues and on public receptions, and scientists and science educators would benefit from pedagogical approaches that take seriously religious resistance to scientific authority. More broadly, scientists and educators of all varieties need new ways to teach scientific knowledge effectively to the public.

Another lesson that can be gleaned from this history is the need to re-examine the behaviour-oriented goals of sex education. If we evaluated the success of school mathematics classes by how many people could complete their own tax forms, we would also have much cause for alarm. Obviously, there are important differences between the topics of mathematics and sex, but instrumentalist assessments can put an unfair burden on education programmes: there are many other reasons that people engage in sexual activity (or fail to ace their taxes), completely unrelated to the type or quality of education programmes they previously encountered or the extent of their learning within those programmes. This calls for critical conversations about why we desire to control what happens beyond the classroom, whether such control is possible, and in what ways it impedes other educational objectives that we have stronger chances of achieving through sex education: concluding programmes with students who are well-informed and have the critical skills to ask good questions and find reliable answers after class is out.

The legacies of religious involvement on the history of sex education in the US will continue to be felt, and examining them will help us better understand our country’s messy and ambivalent approaches to sex today. Those influenced by comprehensive sexuality education might be able to recognise traces of past progressive Protestant influences, including the embrace of science as a way to learn about creation, the interfaith desire to find common ground, and the situation ethics of the new morality. Liberal Protestants also continue to generate some of the most comprehensive sexuality education programmes for religious education and private schools. Those familiar with abstinence-only/sexual-risk reduction programmes might recognise aspects of earlier Protestant purity reforms and midcentury family life education, along with the more direct influence of evangelical pro-family politics. Previous religious sex educators sought to move the conversation forward while also holding on to the reins as best they could. They set the boundaries of what should be considered acceptable in public sex education that would later break into our current divisions.