Back in the fall of 1999, Norman Conard, a history teacher at the Uniontown High School in Kansas, asked his students to come up with a project for National History Day. While brainstorming ideas, ninth-grader Elizabeth Cambers stumbled on an old clipping from US News and World Report. The story included the line, ‘Irena Sendler saved 2,500 children from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942-43.’

Elizabeth asked her fellow ninth-grader Megan Stewart to help her with her project, and during her free time, Megan pored over the story of Irena Sendler. She learned about how this unassuming young Polish nurse had created thousands of false identity papers to smuggle Jewish children out of the ghetto. To sneak the children past Nazi guards, Sendler hid them under piles of potatoes and loaded them into gunny sacks. She also wrote out lists of the children’s names and buried them in jars, intending to dig them up again after the war so she could tell them their real identities.

Imagining herself in the young nurse’s position, Megan could appreciate just how difficult her life-threatening choices must have been. She was so moved by Sendler’s gumption and selflessness that she, Elizabeth, and two other friends wrote a play about Sendler. They called it Life in a Jar and performed it at schools and theatres. As word got out, the students’ quest to share what Sendler had done appeared on CNN, NPR, and the Today Show. The power of Sendler’s story had turned the project into something much bigger than the girls expected.

Today, Megan Stewart – now Megan Felt – is programme director for the Lowell Milken Center for Unsung Heroes, a non-profit organisation that teaches students about the lives of past luminaries such as Sendler. ‘I continue to be inspired by Irena Sendler daily,’ says Felt, who still marvels at the way a single story cracked her own life wide open, completely altering its course. ‘We want young people to be inspired by the stories they hear and realise that they also can change the world.’

The careers of many great novelists and filmmakers are built on the assumption, conscious or not, that stories can motivate us to re-evaluate the world and our place in it. New research is lending texture and credence to what generations of storytellers have known in their bones – that books, poems, movies, and real-life stories can affect the way we think and even, by extension, the way we act. As the late US poet laureate Stanley Kunitz put it in ‘The Layers’, ‘I have walked through many lives, some of them my own, and I am not who I was.’

Our storytelling ability, a uniquely human trait, has been with us nearly as long as we’ve been able to speak. Whether it evolved for a particular purpose or was simply an outgrowth of our explosion in cognitive development, story is an inextricable part of our DNA. Across time and across cultures, stories have proved their worth not just as works of art or entertaining asides, but as agents of personal transformation.

One of the earliest narratives to wield such influence was the Old Testament, written down starting in the seventh century BCE and then revised over the course of hundreds of years. When we think of this first section of the Bible, we tend to recall its long sequences of ‘thou shalt nots’, but many of the most gripping Old Testament stories do not contain an overtly stated moral. While the Old Testament certainly reflected the values and priorities of the culture from which it emerged, those values came embedded in powerful tales that invited readers and listeners to draw their own conclusions. When Eve ate the fruit from the Garden of Eden’s tree of knowledge, bringing God’s punishment upon herself and Adam, the image powerfully illustrated the fate that may await anyone who ignores a divine order. Noah, who carried out God’s cryptic command to build an ark, survived the great deluge that followed – and personified the rewards in store for one willing to conform to God’s will. It was no coincidence that, steeped in stories like these, the ancient Hebrews emerged as a unified society of people devoted to God and his commands.

The Homeric emphasis on conquering cities by trickery is mirrored in later Greek battle strategy

Meanwhile, in ancient Greece, a formidable oral storytelling tradition was taking hold – one in which epic stories such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were passed from generation to generation, each storyteller adding tweaks as he saw fit. Though the characters in these epics were larger-than-life figures, often possessed of superhuman abilities, it was still natural for people to identify with them. Epic heroes rarely conquered their foes with ease. Like Homer’s Odysseus, who endured a painful and protracted journey to return to his homeland, they faced hardship head-on and persevered against great odds.

One reason the epics had such staying power was that they instilled values like grit, sacrifice, and selflessness, especially when young people were exposed to them as a matter of course. ‘The later Greeks used Homer as an early reading text, not just because it was old and reverenced, but because it outlined with astonishing clarity a way of life; a way of thinking under stress,’ wrote William Harris, the late classics professor emeritus at Middlebury College, Vermont. ‘They knew that it would generate a sense of independence and character, but only if it were read carefully, over and over again.’

In their quest to lead a good life, generations of Greeks looked to the epics for inspiration, giving rise to ancient hero cults that worshipped the exploits of characters like Achilles and Odysseus. The historian J E Lendon points out that the Homeric emphasis on conquering cities by trickery is mirrored in later Greek battle strategy, underscoring the tales’ impact not just on minds, but on cultural norms and behaviours.

For thousands of years, we’ve known intuitively that stories alter our thinking and, in turn, the way we engage with the world. But only recently has research begun to shed light on how this transformation takes place from inside. Using modern technology like functional MRI (fMRI) scanning, scientists are tackling age-old questions: What kind of effect do powerful narratives really have on our brains? And how might a story-inspired perspective translate into behavioural change?

Our mental response to story begins, as many learning processes do, with mimicry. In a 2010 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study, the psychologist Uri Hasson and his Princeton University colleagues had a graduate student tell an unrehearsed story while her brain was being scanned in an fMRI machine. Then they scanned the brains of 11 volunteers listening to a recording of the story. As the researchers analysed the data, they found some striking similarities. Just when the speaker’s brain lit up in the area of the insula – a region that governs empathy and moral sensibilities – the listeners’ insulae lit up, too. Listeners and speakers also showed parallel activation of the temporoparietal junction, which helps us imagine other people’s thoughts and emotions. In certain essential ways, then, stories help our brains map that of the storyteller.

What’s more, the stories we absorb seem to shape our thought processes in much the same way lived experience does. When the University of Southern California neuroscientist Mary Immordino-Yang told subjects a series of moving true stories, their brains revealed that they identified with the stories and characters on a visceral level. People reported strong waves of emotion as they listened – one story, for instance, was about a woman who invented a system of Tibetan Braille and taught it to blind children in Tibet. The fMRI data showed that emotion-driven responses to stories like these started in the brain stem, which governs basic physical functions, such as digestion and heartbeat. So when we read about a character facing a heart-wrenching situation, it’s perfectly natural for our own hearts to pound. ‘I can almost feel the physical sensations,’ one of Immordino-Yang’s subjects remarked after hearing one of the stories. ‘This one is like there’s a balloon under my sternum inflating and moving up and out. Which is my sign of something really touching.’ Immordino-Yang reported her findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2009 and in Emotion Review in 2011.

We argue with stories, internally or out loud. We talk back. We praise. We denounce. Every story is the beginning of a conversation, with ourselves as well as with others

As they reacted to the stories, subjects also reported strong feelings of moral motivation. When one participant listened to a story about a Chinese boy giving a warm cake to his mother, even though he was quite hungry, he talked about how it had made him reflect on his relationship with his parents and what they’d given up for him. People identified similarly with story characters in a 2013 study at Amsterdam’s Vrije Universiteit, where fiction readers who felt emotionally transported into a story scored higher on a scale of empathic concern one week after their reading experience.

It’s this kind of gut-level empathetic story response that can inspire people to behave differently in the real world. The Ohio State University psychologist Lisa Libby studied a group of people who engaged in ‘experience-taking’, or putting themselves in a character’s place while reading. High levels of experience-taking predicted observable changes in behaviour, Libby and her colleagues found in 2012. When people identified with a protagonist who voted in the face of challenges, for instance, they were more likely themselves to vote later on.

Of course, many story messages don’t translate into action as neatly as controlled studies might suggest. We respond to The Diary of Anne Frank differently at age 42 than we do at 12, in part because of all the other stories that have changed our perception in the interim. We argue with stories, internally or out loud. We talk back. We praise. We denounce. Every story is the beginning of a conversation, with ourselves as well as with others.

Those kinds of conversations, internal and external, are exactly what educators are counting on to unleash story’s change-creating potential. The non-profit Facing History and Ourselves, active in school districts around the US, brings students lessons that feature true stories from historical conflicts. The biggest transformations, says Facing History executive Marty Sleeper, happen when children actively engage – even empathise – with a particular narrative, recognising how it matters to them. ‘We teach specific pieces in history that have a connection to the present,’ Sleeper says. ‘We’re looking for ways in which kids see that history is connected to their own lives.’

One lesson about the 1938 Kristallnacht attacks delves into the historical narrative, describing how Nazis burned synagogues, smashed windows and looted Jewish shops while most ordinary Germans just watched. This real-life story prompts class discussion that touches on what it means to be a bystander; someone who does nothing while someone else gets hurt. Kids consider how they might have reacted when Jewish people were persecuted under Nazi rule, but they’re also thinking about similar matters closer to home, such as whether they should stand up for a friend who’s being badmouthed. When students explore the significance of stories in this way, their thoughts and choices shift measurably. Children who complete the Facing History curriculum show more empathy and concern for others, and they are more likely than controls to intervene when other students are bullied.

The alternative sentencing programme Changing Lives Through Literature (CLTL) is proving that well-told stories can also re-orient the lives of adult offenders. CLTL began in the early 1990s with a pilot programme that included eight men, some with several convictions to their names. The men would sit around a table with the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth professor Robert Waxler and talk about a variety of different books – from Jack London’s Sea-Wolf to James Dickey’s Deliverance.

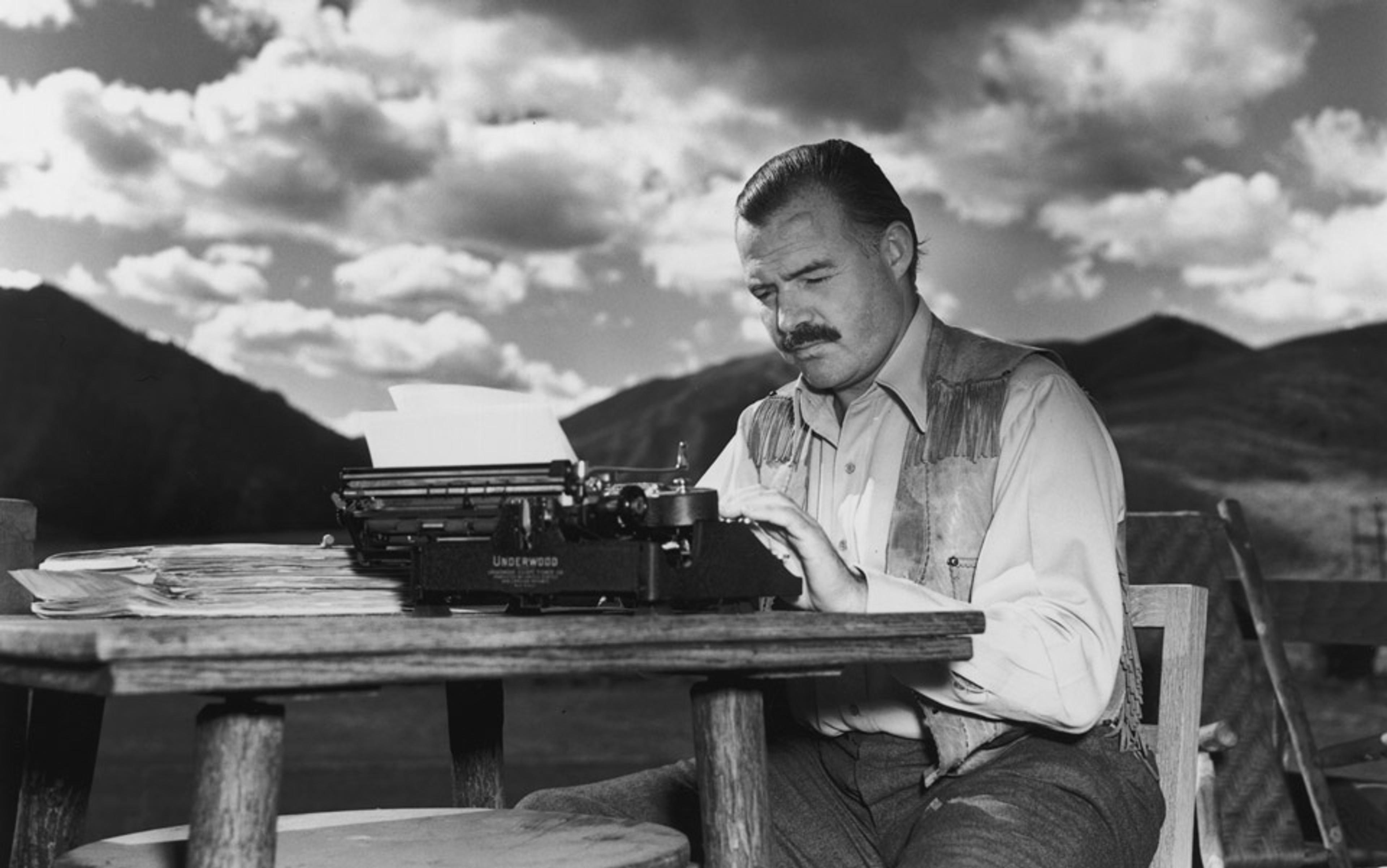

As they read and discussed the stories, the students came away with new, surprising perspectives. One man talked about his identification with Santiago, the beleaguered fisherman in Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. The man said he sometimes felt an inner pull to go back to his drug habit, but that Santiago’s will to persevere motivated him to stay a sober course. ‘The fictional character was alive for the student at that crucial moment, an inspiration, a stranger become a friend,’ Waxler writes. ‘It was not an exaggeration to say that a story had caught this student’s attention and perhaps saved his life that day.’ In a study of 600 participants, rates of criminal activity declined by 60 per cent compared to only 16 per cent in a control group.

Many artists bristle at the idea that they tell stories to get people to think or act in any particular way

The stories we tell ourselves are integral to our wellbeing, too. Depressed people often cling to long-established internal narratives with refrains like ‘I’m not good enough to achieve much,’ or ‘My mother dashes all my most important dreams.’ Counsellors who practice psychodynamic therapy help clients discard these stagnant inner monologues and substitute fresh ones. In a 2005 case study, Rutgers University psychologist Karen Riggs Skean describes one of her patients, a graduate student in his late twenties called CG who was the child of abusive, neglectful parents. CG believed close relationships with others could only hurt him. Living out this narrative had made him lonely, withdrawn, and convinced others were out to get him. At the beginning of treatment, he often told Skean, ‘I’m not sure how helpful today’s session has been.’ But little by little, CG began to let Skean in, telling her stories from his difficult past. In return, Skean helped him see how his early struggles had led him to tell himself certain stories – the world was hostile and cold, people would always reject him – that were not necessarily true.

One day, CG reported that he had actually asked a woman on a date and that he’d enjoyed himself the whole time. When Skean expressed happiness, she recalls, CG ‘began to cry and said that he just realised there had never been anyone in his life who gave him a feeling that he should be happy, should do things that brought him pleasure’. It was a watershed moment, a glimpse at the evolution of CG’s internal narrative. No longer the abused, forgotten child who saw so many forces arrayed against him, he was beginning to see himself as capable, valuable, and worthy of the good things in life. After his therapy concluded, CG went on to thrive and to take high-ranking positions in his academic field.

Of course, some enthralling inner narratives can damage mental horizons. The success of Adolf Hitler’s oratory bid to dominate 1930s Germany should convince us that a narrative’s surface persuasiveness is not, in itself, a virtue. And sensibly enough, many artists bristle at the idea that they tell stories to get people to think or act in any particular way. ‘I’m often asked, “What do you hope readers take from your books?” ’ Newbery Award winner Shannon Hale wrote on her blog. ‘I have a hard time answering that question, because I never write toward a purpose or moral. I just hope that a reader takes whatever she needs.’

When story is at its best – as yarn-spinners like Hale can testify – its effect is expansive rather than nakedly persuasive. Narratives that tell us point-blank who we should be, how we should behave, are better described as dictates or propaganda. The most enduring stories, by contrast, broaden our mental and moral outlook without demanding that we hew to a certain standard. Whether they describe a young nurse risking her life to smuggle children out of the Warsaw Ghetto, a meek older woman who shows grit and selflessness after a surprising tragedy (Alison Lurie’s Foreign Affairs), or a hotel manager who shelters refugees marked out for death (Terry George’s Hotel Rwanda), they present us with an arresting alternative to the way we see the world.

It’s always up to us whether to turn our backs on a story’s landscape or to step into the fresh possibilities it offers. But when we do decide to venture into an unfamiliar story – as did Megan Felt, Waxler’s students, and CG – we emerge as revised, perhaps unexpected, versions of ourselves. Stories allow us to travel, time and again, outside the circumscribed spaces of what we believe and what we think possible. It is these journeys – sometimes tenuous, sometimes exhilarating – that inspire and steel us to navigate uncharted territories in real life.