In 1833, Lydia Maria Child was testing what being a woman meant for the abolition of slavery. Child, a beloved author of novels, self-help books and children’s stories, had shocked readers with a book denouncing slavery: An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans (1833). The Appeal detailed the history of slavery in the United States, exposed the power of enslavers in US politics, and decried the US economy’s foundation in trafficked Africans. It ended with a rebuke of the Northern racism that, Child asserted, allowed slavery not just to survive but to thrive.

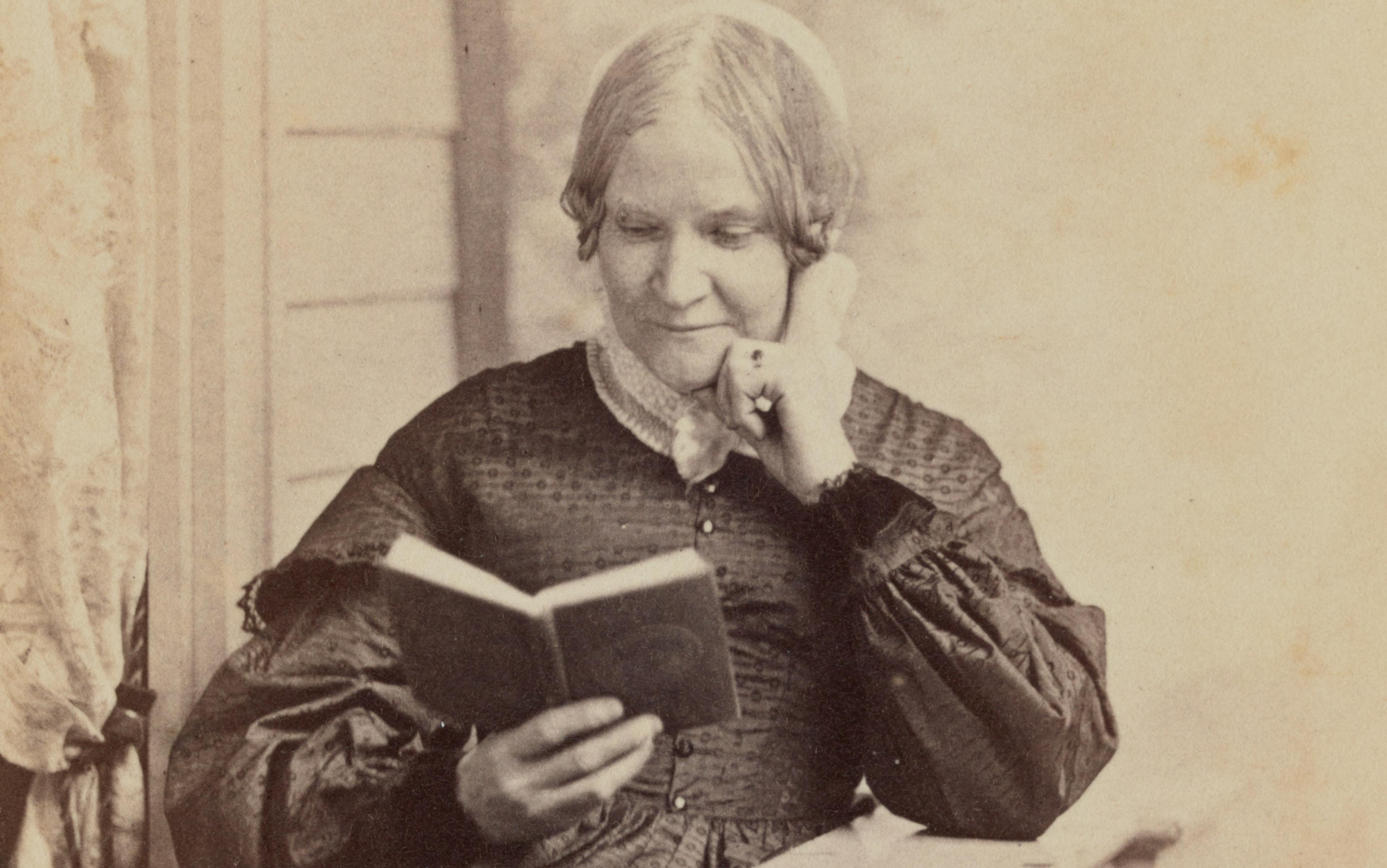

Image courtesy the David Ruggles Center

To denounce slavery openly in 1833, especially for a white American, was to be a radical. Most white Northerners tolerated slavery, assured by statesmen that it was politically necessary, and by religious leaders that it was biblically sanctioned. Of those who opposed it, most assumed that nothing could be done. Child, together with a small group of activists led by William Lloyd Garrison, felt differently. They were not just antislavery. They were abolitionists, convinced that slavery should end immediately and without compensation to enslavers. The hypocrisy of championing US principles of freedom while enslaving others, they argued, was appalling. The exchange of forced labour for national prosperity was shameful. The whole atrocity should end, and now.

Some of these agitators had formed the New England Anti-Slavery Society in Boston in 1832. Early abolitionists were highly literate; some were prosperous; the wide freedom of expression they enjoyed, along with new printing technologies, meant their ideas could spread. Alarmed politicians and clergy began to warn that abolition would crush the young nation’s economy, destroy its unity, and upend the social order. Abolitionists were unmoved. There was a higher moral law and, if abolishing slavery meant the end of the US as they knew it, so be it.

When Child’s Appeal was published, this small band of extremists rejoiced. ‘That such an author – ay, such an authority – should espouse our cause,’ wrote the abolitionist Samuel May, ‘was a matter of no small joy.’ True: abolitionists had seen Child with her husband at their meetings. But they had not suspected ‘that she possessed the power, if she had the courage, to strike so heavy a blow.’ Boston’s polite society, by contrast, recoiled and then struck back. Sales of Child’s other books plummeted; she was ‘assailed opprobriously and treated derisively’; political leaders railed against the woman whose book ‘had presumed to criticise so freely the constitution and government of her country.’ Part of their outrage stemmed from sexism. ‘Women,’ Child was warned, ‘had better let politics alone.’

Child was not going to let politics alone. Nor was she going to let others’ definition of being a woman limit her actions. But greater forces would soon make clear how costly such defiance could be, both for Child personally and for the abolitionist cause, and racial justice, more broadly.

The backlash against her Appeal ended Child’s career as a popular writer, but it also endeared her to the tiny assembly of likeminded women who had thrown in their lot with the abolitionists. The newly formed Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society included Black women like Susan Paul and white women such as Maria Weston Chapman and three of her boisterous, intelligent and happily unmarried sisters. The women discovered both a shared hatred of slavery and a common talent for organisation. They started small but quickly grew. In 1834, they inaugurated a Christmas antislavery fair and turned it into a juggernaut of abolitionist fundraising. They learned how to petition Congress, collecting signatures to protest laws against interracial marriage and the persistence of slavery in Washington, DC. They studied legal theory and used it to erode slavery’s reach in Massachusetts. They even identified a girl brought to Boston by her enslavers, extracted her from their home under the guise of recruiting for Sunday School, and hired a lawyer to sue for her freedom. The successful suit both emancipated the girl and established legal protection for Black Americans in Massachusetts – a decision that held until 1857, when the Dred Scott v Sandford case established that Africans and their descendants had ‘no rights which the white man was bound to respect’.

Maria Weston Chapman, c1846. Courtesy Boston Public Library

Child and others also organised the first national political gathering of Black and white women – the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women – in 1837, where they passed resolutions decrying white racism and condemning the clergy’s apathy. In Philadelphia in 1838, they met again and elected the Black members Susan Paul, Sarah Mapps Douglass and Martha Ball to the executive committee. They discovered physical bravery as well: together, Black and white women faced down anti-abolitionist mobs in Boston and Pennsylvania, sometimes placing their bodies between bellowing rioters and abolitionist speakers, allowing the latter time to escape. As they organised, petitioned, argued and schemed, Child continued writing, this time about women. Her two-volume History of the Condition of Women, documenting women’s lives through the ages and across continents, was published in 1835. The movement grew.

Black women found it more effective and less demeaning to avoid this hypocrisy by forming their own societies

In the mid-1830s, Angelina and Sarah Grimké – natives of South Carolina who had renounced their slaveholding past – joined their ranks, as did a fiery Quaker schoolteacher named Abby Kelley. In the next years, dozens of female antislavery societies were formed from Pennsylvania to Maine as more white women recognised the evil of slavery and the power they had to end it. ‘My wife and grown-up daughters,’ one farmer complained, ‘have got a notion out of some tract they have been reading, that we ought not to eat rice, nor sugar, nor anything that is raised by the labour of slaves.’ ‘We Abolitionist Women,’ Angelina Grimké wrote, ‘are turning the world upside down.’

This was true, but only to a point. If turning the world upside down meant ending slavery, abolitionist women were united. If it meant racial equality, they were not. That slavery should end did not, for many white women, imply that Black Americans were their equals. So, while many female antislavery societies included Black women, both in their membership and in their leadership, some excluded them completely. Others restricted membership to ‘ladies’ only and made clear that ‘lady’ meant white. Black women sometimes found it more effective, and certainly less demeaning, to avoid this insulting hypocrisy by forming their own societies.

‘[E]ven our professed friends have not yet rid themselves of prejudice,’ lamented Mapps Douglass. Kerri Greenidge’s recent book on the Grimké sisters and Linda Hirshman’s work on Chapman also highlight the paternalism with which even the most committed white abolitionists sometimes treated their Black allies. Even those like Child who embraced racial equality also relentlessly advocated ‘uplift suasion’, falsely assuring Black people that white Americans would respect them just as soon as they dressed nicely and talked softly. As these white women well knew, the opposite was all too frequently true.

In addition to their fundraising and petitioning, some women, especially Kelley and the Grimké sisters, began to give antislavery speeches. This, they knew, was a risk. Clergy still widely repeated a biblical exhortation that commanded women to stay silent in public. Disobedience risked more of the ostracism that, as Child’s case had shown, awaited those who crossed religious and political leaders. But the Grimkés and Kelley, it turned out, were powerful orators, and using their newfound talent to promote the cause they loved was exhilarating. ‘My auditors literally sit some times with “mouths agape and eyes astare,” so that I cannot help smiling in the midst of “rhetorical flourishes” to witness their perfect amazement at hearing a woman speak in the churches,’ wrote Angelina Grimké as her audiences swelled. Initially, male abolitionists like James Birney and Lewis Tappan encouraged them. In Child’s case, they tried to shame her into speaking more. Think, Tappan urged her, ‘how much the audience will be interested, if you allow me to announce that Mrs Child of Boston is about to address them.’

As the movement grew, it began to attract more conservative men, including members of the clergy. These men had indeed come around to the belief that humans should not be enslaved. Perhaps they congratulated themselves on their progressiveness. But even if they could imagine the end of slavery, the thought of a woman speaking in public was a bridge too far. After watching in dismay as the Grimkés spoke and Child wrote, they finally objected in print. On 27 June 1837, in what became known as ‘The Pastoral Letter’, the General Association of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts wrote:

We invite your attention to the dangers which at present seem to threaten the FEMALE CHARACTER with wide-spread and permanent injury … The power of woman is in her dependance [sic] flowing from the consciousness of that weakness which God has given her … But when she assumes [a public role], she yields the power which God has given her for her protection, and her character becomes unnatural.

Chapman met the clergy’s warnings with sarcasm. Women had, as she pointedly put it, ‘been too long accustomed to hear the Bible quoted in defence of slavery, to be astonished that its authority should be claimed for the subjugation of woman the moment she should act for the enslaved.’ She then merrily put her sarcasm into verse:

Confusion has seized us, and all things go wrong,

The Women have leaped from ‘their spheres,’

And, instead of fixed stars, shoot as comets along,

And are setting the world by the ears! …

They’ve taken a notion to speak for themselves,

And are wielding the tongue and the pen;

They’ve mounted the rostrum; the termagant elves,

And – oh horrid! – are talking to men!

Some abolitionist men, judging the clergy’s support to be more valuable than the women’s involvement, tried shaming the women into silence. They accused them of introducing the ‘foreign topic’ of women’s rights into the antislavery struggle, exploiting abolitionism to smuggle in feminism. Child fought back in The Liberator newspaper. Women had not, she wrote, introduced the ‘foreign topic’ of women’s rights into the abolitionist movement. It had been introduced for them. It was men’s insistence on curtailing their antislavery work that made the ‘establishment of women’s freedom’ suddenly ‘of vital importance to the anti-slavery cause’. ‘In toiling for the freedom of others,’ she wrote, ‘we shall find our own.’

One letter reminded her ‘that the wrongs & sufferings of the slaves are greater than those of women’

In their proper domain, the Boston Courier asserted, women were ‘lovely as the evening star’; but when inspired to abandon that domain for realms they could not understand, very little could ‘outmeasure the evil that might follow’. It was not just where they were but what they were doing. ‘We hope that Anti-Slavery Society Ladies will cease so far to forget the dignity and delicacy which should mark the deportment of their sex,’ wrote the Reverend Joseph Tracy.

Soon, even the women’s original allies – fellow abolitionists who had urged them not ‘to let any foolish scruples’ about their gender ‘stand in the way of doing so much good’ – began to urge them to withdraw. One letter to Child, calling on the ‘magnanimity of women’ and reminding her ‘that the wrongs & sufferings of the slaves are greater than those of women’ – asked women, in effect, to stand down for the good of the cause. ‘[Y]ou never saw,’ concluded the Boston abolitionist Caroline Weston, ‘such a piece of malicious twaddle as his letter was.’

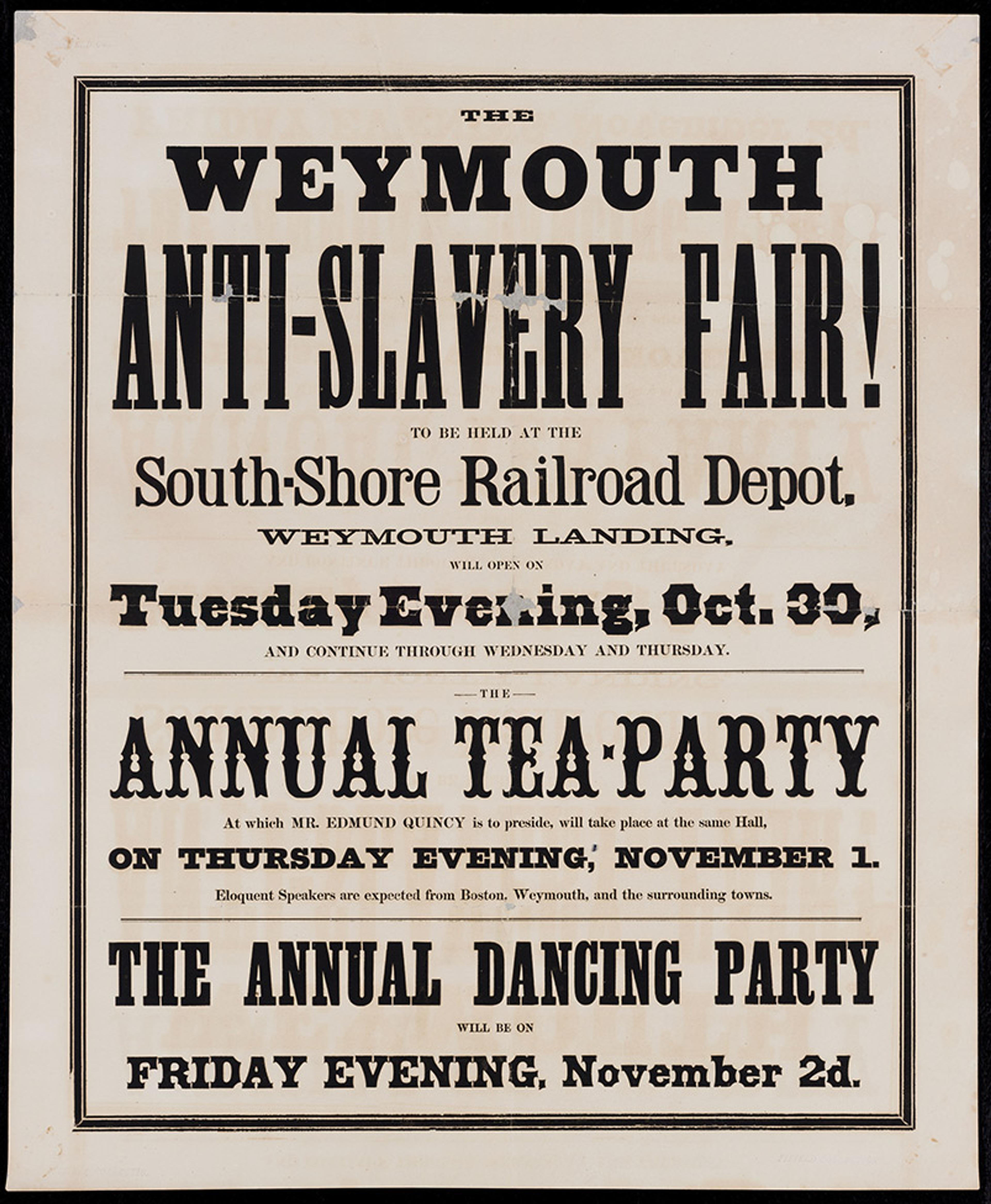

Poster for an Anti-Slavery Fair in Weymouth, Massachusetts, c1830-1860. Courtesy Weymouth Public Library/Tufts University

When the women proved incalcitrant, conservative clergy essentially offered abolitionist men a deal. They would lend their support – along with the social and financial capital that implied – to the movement. But the women would have to go home. Suddenly, the momentum the women had built – the fairs, the petitions, the legal advocacy and physical bravery – stalled as it became necessary first to fight the men who wanted to prevent them from doing any of it.

In their search for an argument that would allow them to continue working, some white women settled on a powerful analogy. The men in question had apparently been persuaded that slavery was wrong. What if they compared themselves to slaves? There were, some women began to argue, distressing similarities. Women were not persons in the eyes of the law. Everything they inherited or earned belonged to their husbands. Their education and employment options were severely limited. They were almost entirely at the mercy of their husbands’ whims and misconduct. Were these things not also true of slaves? The comparison began to feel like a revelation. ‘We have good cause to be grateful to the slave,’ Kelley said. ‘In striving to strike his irons off, we found most surely that we were manacled ourselves.’ The analogy gained momentum.

Authors such as bell hooks and others have long pointed out that this analogy was absurd in scale and toxic in effect. It placed white women’s real but comparatively small sufferings on a level with enslaved women in the South, many of whom were subjected to backbreaking work and sadistic punishments, vulnerable all the while to enslavers who could rape them and then sell their own children. It also focused its appeal for sympathy on white women while free Black women, who were oppressed by the same legal restrictions as white women, bore additional burdens of entrenched poverty, degrading work and violent prejudice. ‘Tell us no more of southern slavery,’ the Black abolitionist Maria Stewart pleaded, ‘for with few exceptions … I consider our condition but little better than that.’

Insofar as marriage resembled slavery, it was indeed in desperate need of reform. But how were Black women to take this increasing focus on white women’s suffering? Some quite simply did not. ‘You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs,’ Frances Ellen Watkins Harper admonished her white allies some time later. ‘I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.’

One of the movement’s dominant analogies was built on a gross mischaracterisation of their own status

The escalating rhetoric among white women – Grimké’s arguments, Child’s exhortations, Chapman’s sarcasm, Kelley’s stridence – had another effect. More conservative women began to feel uneasy. When the much-respected author Catharine Beecher wrote in 1837 that ‘whatever … throws a woman into the attitude of a combatant, either for herself or others … throws her out of her appropriate sphere,’ some of them feared she was right. When Chapman attacked the clergy in her annual report for the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, more conservative members asked her to moderate it. When she refused, they issued a disclaimer. She resigned in fury. Before long, the organisation had split.

When the Quaker teacher Kelley was nominated for the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York in 1840, several of its leading members walked out, unwilling to participate in an organisation that included female leadership. ‘In Congress the masters speak while the slaves are denied a vote,’ Kelley responded. ‘I rise because I am not a slave.’ By the next day, opponents of women’s participation had quit the American Anti-Slavery Society and founded a rival group.

The 1840s, then, found a movement not just in fractious disarray but depending on an argument adopted by white women to defend themselves from chauvinism. The argument created a strange psychological space that allowed white women to be both condescending and self-pitying. It meant that one of the movement’s dominant analogies was built on a gross mischaracterisation of their own status as compared with the people whose sufferings they claimed to champion. As their former allies urged them to retreat, some white women also became embittered by claims that their rights were of secondary importance or – worse – at odds with those of Black people. The stage was set for a bitter conflict that erupted when slavery had been eradicated but the racism it had produced grew in some ways more entrenched.

Two decades and a Civil War later, the question facing the US was not whether women should speak but whether they could vote. Postwar suffrage was expanding, but to whom? Given that there was little political appetite among white men for allowing both Black men and all women to vote, women were again told that their rights were secondary. Some quickly agreed. ‘That the loyal blacks of the South should vote is a present and very imperious necessity,’ Child wrote in the Independent in 1867. ‘The suffrage of woman can better afford to wait.’ Elizabeth Cady Stanton, by then a leading warrior for white women’s rights, disagreed. When it became clear that the Fifteenth Amendment would extend suffrage to Black men but not to any women, she decided to oppose it. She turned to racist rhetoric to convince others to oppose it as well. ‘Think of Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung,’ she urged her readers in 1868, ‘who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence.’ Now, she said, imagine this band of misfits ‘making laws for Lydia Maria Child.’

They laid down barriers to true solidarity among Black and white women that still exist today

Child was ‘vexed beyond measure’ by Stanton’s racism. When Stanton wrote an editorial entitled ‘All Wise Women will Oppose the 15th Amendment,’ Child called it ‘the most impardonable of all her doings.’ ‘Surely we ought to have learned, by this time that the rights of one class of people can never be secured by taking away the rights of another,’ she lamented. But this was not the lesson that Stanton and her allies had learned. Instead, they had learned that racist arguments often worked. Expanding the vote to Black men, Stanton began to warn, would lead to ‘fearful outrages on womanhood, especially in the southern states.’ At a meeting of the American Equal Rights Association in May 1869, Stanton engaged in public and painful disagreement with Frederick Douglass and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper about whose rights should be honoured first. The tension led to yet another split. Those who favoured the Fifteenth Amendment founded the American Woman Suffrage Association to compete with Stanton’s National Woman Suffrage Association. The schism again set back movements for racial justice and women’s suffrage: much, no doubt, to the joy of the enemies of both.

Who is the culprit here? Surely white women bear much of the blame. But in judging when movements for justice go wrong, we must look to the original wrong. White men were the primary architects of both slavery in the US and the stifling injustice that characterised marriage. They had created impossible choices faced by abolitionist women and punished them with ostracism when they did not comply. They had fostered an atmosphere in which racist arguments like the ones some white women used were effective.

And then the harms had multiplied. When white women deployed these arguments, they deepened the injustices they claimed to be fighting. They laid down barriers to true solidarity among Black and white women that still exist today. It is such contamination born of oppression that, no doubt, was what prompted Child to write one of the darkest sentences of her entire correspondence. ‘Deeply, deeply do I feel the degradation of being a woman,’ Child wrote to Angelina Grimké in the 1830s as the ‘woman question’ raged: ‘Not the degradation of being what God made woman, but what man has made her.’ This Women’s History Month, may we resolve to end this degradation and any poisonous analogies that perpetuate it as well.