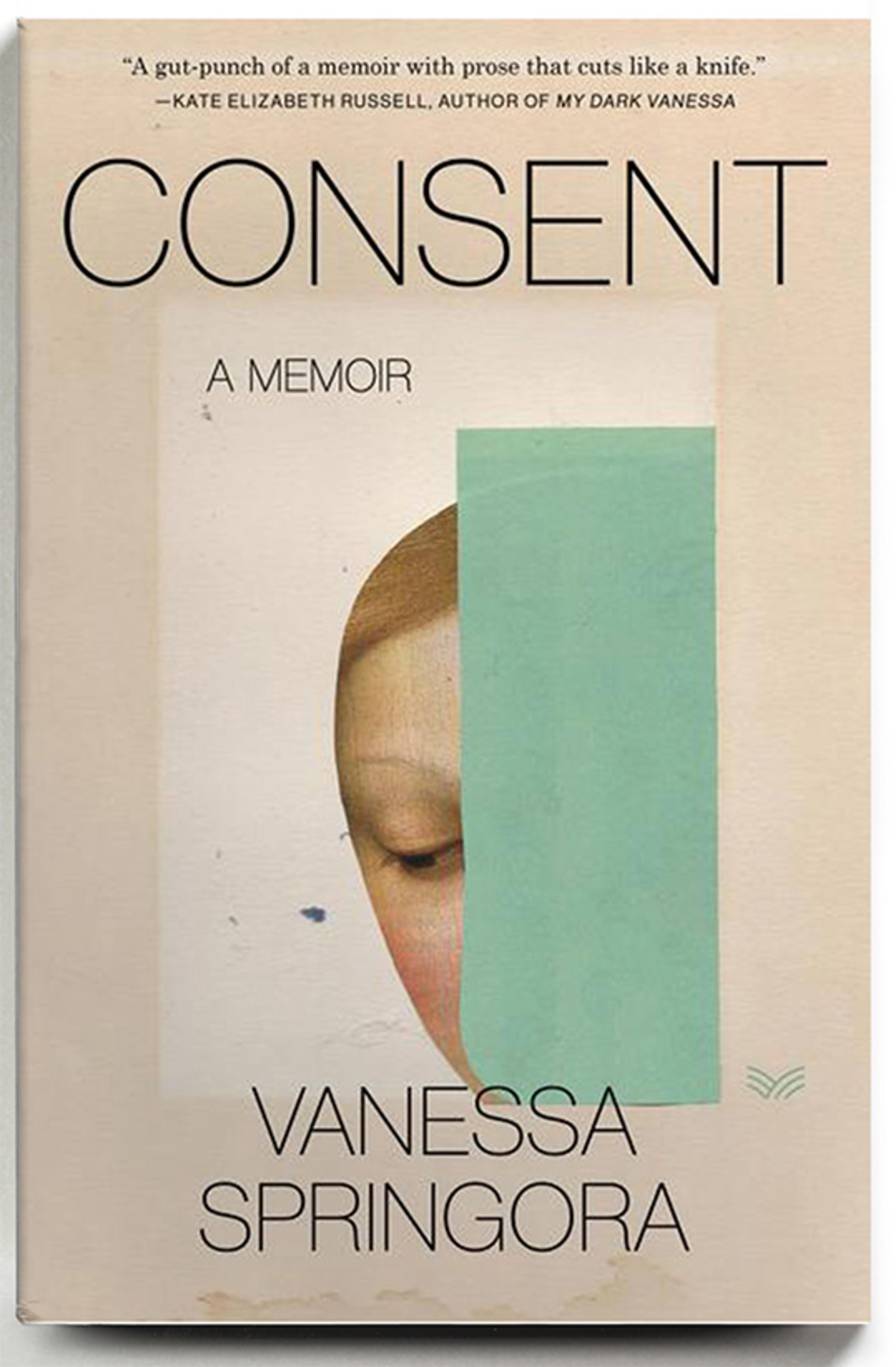

In January 2020, Le consentement (Consent) by Vanessa Springora was published, a memoir exposé of Gabriel Matzneff, a well-known and much-respected French writer, but also a shameless predator of teen girls and preteen boys. Springora charts her two-year relationship with Matzneff, which began in 1986, when she was 14 and he 49, and critiques the cultural landscape that allowed it to happen, the complicity of her mother, and the intellectual and artistic circles that revolved around the Parisian neighbourhood of Saint-Germain-des-Prés where they lived. A year later, there was another astonishing exposé, La familia grande (2021) by Camille Kouchner – the daughter of France’s former foreign minister, Bernard Kouchner – documenting the incestuous relationship between her stepfather, the academic and politician Olivier Duhamel, and Kouchner’s twin brother, then aged 14.

Springora and Kouchner broke years of silence with these testimonies, laying bare the sexual violations these men committed, and landing a bomb right into the centre of the French elite who had allowed them to escape blame for so long. The bomb site is still smoking. Yet, barely two years ago, Matzneff was given safe refuge in his own country, where the authorities chose to turn a blind eye to his unashamed paedophilia – clear to anyone with eyes to see, given that he wrote up his exploits in widely published books. He was a recipient of a writer’s allowance by the Centre national du livre (National Centre of the Book), and in 1995 the minister of culture awarded him the Order of Arts and Letters in recognition of his contribution to the arts and literature. In 2013, he was awarded the Renaudot, one of France’s most prestigious literary awards (his friends were on the panel). But, paradoxically, this award was also the first unravelling, finally driving an outraged Springora out of hiding.

Springora was introduced to Matzneff when she was 13, at a family friend’s dinner party she attended with her mother. She recalls how he seduced the guests with his charisma, but his eyes were always on her. Her mother flirted for his attention and offered to drive him home; despite knowing his preference for young girls, she allowed her just-teen daughter to sit beside him on the backseat where ‘something magnetic passed between us. He had his arm against mine, his eyes on me, and the predatory smile of a large golden wildcat.’

What followed was his grooming of Springora through a series of intensely complimentary letters, sometimes writing twice a day. When she finally wrote back to him (she’d just turned 14) he ‘pounced’. He would wait for her on the street, devising an impromptu encounter, then invited her to his apartment, for pastries, where he kissed her.

Springora is honest about her infatuation with Matzneff in the early months of their relationship, about the novel intoxication of being desired so profoundly. In some ways, she is the classic victim, abandoned by a father who had no interest in her, and with a mother who worked long hours. She was bookish, reclusive, different from her peers, but could be independent minded and fierce when her mother attempted to intervene. She was progressive and spirited, radical in her outlook. Matzneff had chosen wisely. This was a young girl who would be intrigued, admiring even, of her predator’s distain for the bourgeois family.

Matzneff assumed the role of mentor, telling himself perhaps that his actions lay within the traditional Hellenic framework of pederasty, a romantic relationship between a teacher and student, generally considered to be more emotionally driven than sexual. He showed an interest in Springora’s schoolwork, helped her write her essays, let her walk with him through the Luxembourg Gardens, privileging her with his attention, an elegant award-winning literary hero. All the same, he was discreet. He was careful that his predations were seen to be within the law. French law did not legislate an age of consent at this time, but stated that, while a relationship with a minor under the age of 15 was illegal, it was not automatically considered statutory rape. Springora was not protected as were her European sisters. Matzneff was puffed up with self-justification, standing by his belief that his relationships with adolescent girls were helpful to them. We don’t have to look far, though, to detect his self-serving motivations, and his manipulations and abuse of his power.

When lying together in bed surrounded by books, Matzneff relayed the history of literature to the young Vanessa, only this history was conveniently specific to stories of older men with young muses; Edgar Allan Poe who married little Virginia when she was just 13, and Charles Dodgson (better know as Lewis Carroll) and his controversial photographs and obsession with Alice Liddell. One of the most shocking passages in Springora’s book describes the first time Matzneff attempts to make love to her, and her body involuntarily rejects him ‘[w]ith an instinctive reflex, my thighs jammed tight together’ – clearly telling her something that her emotions were not yet fully aware of. Instead of respecting this obvious sign – ‘I howled with pain before he even touched me’ – he turned her over. ‘That is how I lost the first part of my virginity,’ she writes. ‘Just like a little boy, he whispered to me in a soft voice.’

Matzneff used adolescent girls as muses, but also ventriloquised them as characters in his novels, cannibalising his relationships with them as well as the love letters they exchanged, all without permission. He stole their identities and remade them to serve his literary ego before they had even discovered their true selves. A decade before meeting Springora, he’d had a three-year relationship with Francesca Gee, beginning when she was 15 years old, who, some years later, came across an illustration based on a photograph of herself on the cover of one of Matzneff’s novels, Ivre du vin perdu (1981; ‘drunk on lost wine’), strolling by a bookshop window. The novel follows a middle-aged man Nil and his seductions of 15-year-old girls, and trips to Manila where he pays to have sex with 11-year-old boys. For four decades, with no regard for her or attempt to obtain her consent, Gee’s image was used to promote the kind of abusive relationships for which Matzneff is now being held to account.

By using these young women’s letters, Matzneff sought to demonstrate that a consensual love affair could happen between an adolescent and an adult, that love could transcend generations. Even now, in his senescence and facing a five-year prison sentence for sexual abuse, he marshals that cynical intellectual cover favoured by predators who target minors, and insists that Gee and Springora were two of the three loves of his life. These predators kindle an erotic storm by corresponding with these girls, then fan the flames by demanding their urgent response, and voilà – here is the proof of the young girl’s love for them. ‘A letter leaves a trace,’ Springora writes, ‘and the recipient feels duty-bound to respond, and when it is composed with passionate lyricism, she must show herself to be worthy of it.’

Matzneff wrote many books, one a year at the height of his career, and was celebrated for his transgressions, a French symbol of political anti-correctness. In Les moins de seize ans (1974; ‘the under-16s’), he claims: ‘To sleep with a child, it’s a holy experience, a baptismal event, a sacred adventure.’ The book, published in 1974, was republished in 2005. Narcissistically, he continues:

What captivates me is not so much a specific sex, but rather extreme youth, the age between 10 and 16, which seems to me to be – more than what we usually mean by this phrase – to be the real ‘third sex’.

Perhaps Matzneff is right. This liminal place of adolescence needs to be more clearly defined, to exist uniquely and separately from both childhood and adulthood. It is a mutable state, on the cusp, its enigmatic quality resisting our full understanding. As the American photographer Sally Mann writes in her photographic collection At Twelve (1988), a series of images of girls, full of symbol and story at this conflicted age:

What knowing watchfulness in the eyes of a 12-year-old… at once guarded, yet guileless. She is the very picture of contradiction: on the one hand diffident and ambivalent, on the other forthright and impatient; half pertness and half pout.

An image from this book springs to mind: a young teenage girl in an easy-fit swimsuit, sitting sideways on a white chair, her legs slung over the arm, the toes of her left foot coyly curled into the toes of her right. Her hair is dripping wet, her thighs and breasts are beginning to take shape, but she looks directly at her viewer, challenging, sullen. She is brimming with the frenzy of budding life, of which she knows nothing. She is excited by the changes in her, yet also fears them. She wants and does not want the attention of the person looking.

Adolescence was first treated seriously as a different kind of consciousness in the evolution of the child in the book Adolescence (1904), by the inaugural president of the American Psychological Association, G Stanley Hall. It came about, he claims, only because of changes in child labour laws and universal education: youth had gained more time – some may call it empty, listless, kicking-about time – before the responsibilities of adulthood were to weigh in. More time, combined with mood swings and sudden bursts of outraged anger at authority, what Hall described as ‘storm and stress’; but also, and perhaps more problematic still, the flowering of the pleasure-sensitive, subcortical parts of the brain that make a teenager susceptible to risk-taking.

The responsibility for a man’s behaviour rests squarely on her small shoulders

Adolescents are not children. Not once puberty has set in and their hormones rage, not once they are sexually mature and able to conceive a child. But, emotionally, they are not yet adults. This tension makes them the perfect subject for the artist and writer, attention grabbing in both their beauty and controversy. Take Balthus, for instance, whose paintings of girls in languorous dreamy poses divide opinion: some critics see them as voyeuristic expressions of perverted male desire; others appreciate how he captures the spirit of the adolescent in reverie. But it also feels convenient that Balthus resisted being critiqued: ‘Balthus is a painter about whom nothing is known,’ he said rather pompously, managing to keep his life and motivations private. But also abdicating responsibility, blaming the viewer’s response, good or bad, on their own perception. The painting should speak for itself, much like the literary theorist Roland Barthes’s declaration in his essay ‘The Death of the Author’ (1967) that the writer’s biographical details were irrelevant when reading a text, that author and creation are not related.

Looking at Thérèse Dreaming (1938) by the Polish-Swiss painter Balthus. Photo by Ullstein Bild/Getty

Does this simply allow the artist to step away from the spotlight once the critics swing the beam his way? The novelist and literary critic Zadie Smith argues, in her essay ‘Fail Better’ (2007), that an artwork cannot escape the personality of its creator: ‘Personality is much more than autobiographical detail, it’s our way of processing the world, our way of being.’ It was Balthus’s choice to paint a nameless girl with one foot on a stool to expose her pure white knickers, her head turned away, her eyes closed, a cat at her feet hungrily licking cream from a bowl. And his choice to make her the passive focus of her voyeur: she is a blank space, unable to challenge any fantasy projected onto her, however sexually transgressive.

Yes, perhaps Matzneff has drawn our attention to the mutability of the adolescent, but, from what we now know about him, his admiration is entirely self-serving. Springora has identified ‘the type’ who is sexually attracted to the teenager, which has wrongly become synonymous with paedophilia. There is a name for this: ephebophilia. Ephebophiles are sexually aroused by puberty itself, unlike paedophiles, who are sickened by the first sprout of pubic hair. Vladimir Nabokov explores this condition with forensic and uncomfortable detail in his novel Lolita (1955), dissecting Humbert Humbert’s obsession with ‘nymphets’: ‘Lolita … of the bangs and the swirls at the sides and the curls at the back, and the sticky hot neck, and the vulgar vocabulary – “revolting”, “super”, “luscious”, “goon”, “drip” – that Lolita, my Lolita.’

Springora suggests that ephebophiles are perhaps psychologically suspended at this age themselves: ‘His [Matzneff’s] psyche is that of an adolescent. And when he’s with a young girl, he feels like a 14-year-old boy. That’s the reason he doesn’t think he’s doing anything wrong.’ Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert was driven to re-enact his lost and thwarted teenage love affair with Annabel Leigh. Or is this another excuse? There is also the simple primitive appeal of the virgin, untouched, no risk of disease. A man wants to brand his hot iron on her beautiful new skin – I Was Here. I Was The First.

But Nabokov captures something else that is an essential part of the predator’s ammunition:

Between the age limits of nine and 14 there occur maidens who, to certain bewitched travellers, twice or many times older than they, reveal their true nature which is not human, but nymphic (that is demoniac); and these chosen creatures I propose to designate as ‘nymphets’.

Demonic because they are seductive. The responsibility for a man’s behaviour rests squarely on her small shoulders. He calls her inhuman because she tempts men to defy the law.

But what if the ephebophile’s grooming of her, within a permissive culture that refuses to censor it, has created this seductress, sexualised beyond her developmental age, promoting her desirability for his needs before she has had a chance to discover her own? If this girl-child is a seductress commanding her own sexuality, able to give consent, then she has no defence when the accused retorts: ‘But you had a choice!’ And when she grows into a woman, and loses her youthful appeal, becoming wise to his manipulation, the seductress tag makes it easier for him to scorn her. In Le consentement, Springora recounts how Matzneff lashed out when she finally challenged him about his preference for boys in Manila. ‘You’re mad,’ he retorts:

You don’t know how to live in the present, just like every other woman. No woman is capable of savouring the moment, it’s as though it’s in your genes. You’re all chronically unsatisfied, forever imprisoned by your hysteria.

Much in the way that progressive liberal countercultures flourishing in the 1970s, in the United States and the United Kingdom, pushed back against the legacy of postwar mundanity, France was going through its own liberal revolution, on the coat-tails of the May 1968 protests, condemning collective societal conventions in defence of the individual. Suddenly ‘No!’ was a very unsexy word. In France, with liberté as a core value in its cultural fabric, permissiveness perhaps inevitably extended to sexuality, with child sexuality caught up in the mix: any limits on behaviour due to age were considered disrespectful to children as sovereign beings.

In the late 1970s, a wave of opinion pieces in French Left-wing newspapers defended adults accused of having relationships with adolescents. Spurred by the detention of three men awaiting trial for having had sexual relations with two minors, aged 12 and 13, Le Monde published an open letter in 1977 in support of the decriminalisation of sexual relationships between adults and minors under the age of 15. ‘French law recognises in 13- and 14-year-olds a capacity for discernment that it can judge and punish,’ the letter stated. ‘But it rejects such a capacity when the child’s emotional and sexual life is concerned.’ The signatories argued for the right of minors to have a volitional sexual life. Among them were eminent intellectuals, philosophers and psychoanalysts: Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, André Glucksmann and Louis Aragon.

Two years later, Libération published another petition, this time in support of a man who had sexual relations with girls aged between six and 12. ‘The love of children is also the love of their bodies,’ the petition stated, claiming that the girls were happy to be with the man in question. This petition was signed by 63 people, again including well-known intellectuals.

But, as the sociologist Pierre Verdrager explored in his book L’enfant interdit (2013; ‘the forbidden child’), a study of the cultural landscape that allowed paedophilia to grow unchallenged in the 1970s, the mood of liberty was hijacked by pro-paedophilia activists, who gained leverage within intellectual circles. France boasted ‘an aristocracy of sexuality’ according to Verdrager, ‘an elite that was united in putting forth new attitudes and behaviour toward sex’. This aristocracy was not bound by the norms of a moral code; they were superior to ‘ordinary people’ and, in promoting sex between adults and minors, they rebelled against the bourgeois order. Their opponents were considered reactionary and puritan, thereby casting paedophiles as victims of retrograde legislation. This was a time of free sexual expression – whatever the individual’s age.

Muriel Salmona, a French psychiatrist and president of Mémoire Traumatique et Victimologie (the Traumatic Memory and Victimology association) stated in an interview in The Atlantic in 2018 that what these intellectuals didn’t know was that they had been colonised ‘by the discourse of paedocriminals’. She said it is a ‘legal horror’ that France did not have an age of consent at the time, and that the 1970s and ’80s in France was an ‘atrocious’ era for children. The hypocrisy is so clear today. While the liberal movement appeared to defend the child’s sexual autonomy and right to an emotional relationship with another person, whatever age, it more fundamentally enabled men ‘twice or many times older than they’ to shrug off any guilt at instigating such relationships by placing it instead on the seductress, the girl-child herself.

Matzneff also signed Le Monde’s open letter and, in 2013, he revealed that he was its initiator, claiming he had no trouble finding signatories. His allies belonged to small liberal groups far removed from the realities of family life, but their influence was widespread, and often reflected in the media’s salacious interest in intergenerational relationships.

Such relationships appear to have been far more visible, if not also more common, in the 1970s and ’80s, and were splashed across the tabloids, feeding our strange condoning curiosity. The film director Luc Besson had a relationship with the actress Maïwenn Besco, a 15-year-old when he was 32. By 16, she had had his baby. Serge Gainsbourg had an international hit with his controversial song ‘Lemon Incest’ (1984), about his 12-year-old daughter Charlotte who, in the music video, lies with him on a large white bed, dressed in a shirt and knickers, and sings:

Your kisses are so sweet …

I love you more than anything,

Daddy, daddy.

The love we’ll never make together

Is the rarest, the most disturbing,

The purest, the most intoxicating.

Then there’s the popularity of male-directed films that explored the theme of the teenage femme fatale and her sexual awakening. In À nos amours (1983; To Our Loves) a 15-year-old Parisian girl goes on a promiscuous rampage to try to escape her abusive family. Interestingly, the film’s director Maurice Pialat plays her abusive father. Whose sexuality are we exploring here?

Woody Allen scripts Isaac chastising Tracy for loving him despite continuing to have sex with her

Recently, I watched Manhattan again, pitched as the director Woody Allen’s ‘love letter to New York’ – a massive success in its day, up for two Oscars, and still considered by many his masterpiece. Released in 1979, it was evidently not a time to question the moral implications of a divorced, bespectacled and balding man of 42 (Isaac, played by Allen) screwing a 17-year-old schoolgirl (Tracy, played by Mariel Hemingway). In a scene set at the restaurant Elaine’s, Isaac is self-deprecating and self-pitying over his guilt at dating a girl so young she has to get up in the morning to attend an exam, while his middle-aged friend is openly jealous.

Controversy has hounded Allen, since he stood accused in the 1990s by one stepdaughter, Dylan Farrow, of sexually molesting her when she was seven, and then subsequently married another stepdaughter, Soon-Yi Previn, 35 years his junior. But it was only in the wake of #MeToo in 2017 that Manhattan was reappraised. As Claire Dederer pointed out in her Paris Review essay on the monster-genius: ‘Allen is fascinated with moral shading, except when it comes to this particular issue – the issue of middle-aged men fucking teenage girls.’ As Isaac sits with Tracy beneath the lamplight in his apartment, he calls the shots: ‘We’re having a great time, and all that. But you’re a kid,’ he says. ‘Never forget that, you know, you’ve got your whole life ahead of you –’

‘Don’t you have any feelings for me?’ she asks.

‘… you don’t want to get hung up with one person at your age … You should think of me… sort of as a detour on the highway of life – so get dressed because I think you gotta get outta here.’

‘Don’t you want me to stay over?’

‘I don’t want you to get in the habit, you know, because the first thing, you know, you stay one night, and then two nights and then … you’re living here.’

Not only does Allen fail to give Tracy character, he scripts Isaac chastising her for loving him despite continuing to have sex with her. Dederer observed that Allen wants us to experience Tracy as ‘good and pure in a way that the grown women in the film never can be … She’s glorious simply by being: inert, object-like, vorhandensein [it’s available].’

Hemingway later revealed in her memoir Out Came the Sun (2015) that, when she turned 18, Allen came to her family home asking for permission to take her to Paris, and, despite her cautioning her parents that she sensed his intention was that the two of them would share a room, and possibly a bed – ‘I wanted them to put their foot down’ – they encouraged her to go with him. It was Hemingway who told Allen, going into the guest room in the middle of the night, that she knew what he was planning and did not want to go.

There has been such a fundamental shift since #MeToo that a figure like Allen is considered at worst perverted, at best ridiculous, for thinking a young and beautiful woman might be interested in him. Imagine a celebrity approaching 50 openly declaring his love for a pubescent girl, as the musician Bill Wyman did for the singer Mandy Smith in the mid-1980s (‘She took my breath away’; ‘She was a woman at 13’), their images splashed across the papers for our disapproving yet voyeuristic appetite. Only in 2019 could Wyman finally admit: ‘I was really stupid to ever think it could possibly work.’

In 2017, in direct response to #MeToo, 100 prominent French women, including the actress Catherine Deneuve, signed an open letter defending France’s long tradition of gallantry, published in Le Monde – the same newspaper that published the defence of intergenerational relationships 40 years previously. It is very much part of French culture to question and disturb, to stand in the conflicted space between two opposing positions, one that protects and one that provokes, egalitarian but also revering of its elite. The open letter’s resistance to any moralistic backlash was perhaps expressive of a fear of the strangulation of creative, artistic and sexual expression. This is also very much the position of the adolescent, ‘diffident and ambivalent … forthright and impatient; half pertness and half pout,’ as Mann described her. Rape is a crime, but seduction is not, was the signatories’ message, speaking against what they considered a new puritanism.

This open letter met with a media outcry, accusing its signatories of being too overprivileged to understand women’s issues today, of being stuck in the 1970s. Le Monde (and Libération) went on to issue apologies for publishing the original open letters defending intergenerational relationships, arguing that, in any period of history, the media simply reflects the ideas of the day. But the refrain ‘It was different then’ is a lame excuse. How misguided it seems to blame emotional and sexual abuse of minors on an experiment led by the bohemian avant-garde. In our post-Freudian world, can’t we now finally shift the focus from the girl as seductress to the man as predator, as delusional, as selfish, as narcissistic, and as inadequate?

How do we marry an adolescent’s private power with the response of others, mostly men, mostly older?

As a young woman who had not yet found a voice to express why it was undermining for me to date men twice my age, I found solace in Mann’s photographs of beautiful teenage girls. Now I see these images with more clarity. Despite her direct stare, one of Mann’s girls curves her whole body, her whole self, away from her mother’s swaggering boyfriend who stands too close. Looking at another photograph, I feel uneasy about the teenager who stands on the porch of a playhouse, and the possessiveness of her father, suited and tall behind her, his arm a slash across her clavicle, his hand a vice on her forearm. As Ann Beattie suggested in the introduction to At Twelve: these girls still exist in an innocent world in which a pose is only a pose – what adults make of that pose may be the issue. I know now how vulnerable the teenage girl is to the viewer’s projection. The predator sees the seductress and the tease; the empathetic witness sees the excitement of her burgeoning power to attract, and the potential for abuse. I know why an artist is drawn to this ambiguity, but I wonder what she owes to her model?

Mann was to have a rude awakening when she published her next book of portrait photographs in 1992, this time capturing her three children (all under the age of 10) playing unselfconsciously in acres of wild farmland in Virginia, doing what children do when they live in a rural environment – and what was also natural for their mother, who herself spent much of her early childhood in the same landscape, defying her parents’ attempts to make her wear clothes. In many of the photographs, Mann’s children are naked, but Immediate Family landed in a world that had moved on from the free expression of the 1970s and ’80s and become more aware of the photographer’s power to shape meaning, and also more sensitive to the exploitation and abuse of children. The New York Times Magazine questioned whether Mann had failed in her mothering duty to protect her children from harm. Mann wanted to capture ‘the full scope of their childhood … – bruises, vomit, bloody noses, wet beds – all of it.’ The images in Immediate Family might be sensual, but they are not sexual; nonetheless, Mann was unprepared for the personal scrutiny that followed the book’s publication.

Still, to me, At Twelve is the more interesting collection, its tension more discomforting for posing a question that’s almost impossible to resolve: how do we marry an adolescent’s private power, the natural development of her body and her wish to walk into the world as a confident and desirable – and empowered and desiring – young woman, with the response of others, mostly men, mostly older?

In Springora’s book Le consentement, I was touched by the power of her writing to not only expose the hurts but also to re-form her identity and rediscover herself. In ventriloquising her, Matzneff cut out her tongue – a kind of narrative colonisation – and it took her until she reached her 40s to claim her own story. In finding her voice, Springora was able to forgive herself for her complicity in this drama, and place the blame where it belonged, on the shiny bald head of her elderly predator.

Both Springora’s and Kouchner’s books and the conversations they’ve stirred have created a significant cultural shift in France. All three of Matzneff’s publishers have dropped him, and former supporters have distanced themselves from both Matzneff and Duhamel, the wilful silence of the obliging bohemian intelligentsia now working against them. Wind was blown into the sails of the resistant French #MeToo movement, and #MeTooInceste was formed, with countless revelations and testimonies shared. But, most importantly, both books have given the conclusive nudge to the French government to finally commit to a more transparent law to protect minors, introducing a legal age of consent at 15, in April this year, in line with other European countries (where age minimums range between 14 and 16), with a charge of rape and 20 years’ imprisonment if an adult has sex with a minor. Previously, prosecutions in France relied on proof of coercion through ‘violence, constraint, threat or surprise’, which often leaned in favour of the perpetrator rather than the victim.

People were persuaded by Humbert’s dream, and now we have woken up

Kouchner always expected that the investigation against her stepfather would be dropped because the statute of limitations had expired (the abuse happened more than 30 years before). But she wrote the book because she wanted her children to know the truth and hoped her story would bring awareness of the prevalence of incest in French society. Duhamel admitted to the abuse, and The New York Times stated that ‘had the statute of limitations not expired, “the facts revealed or alleged” in the investigation would have “led to prosecution”.’

Back in 1975, Nabokov, interviewed on Bernard Pivot’s televised literary show Apostrophes, wisely observed: ‘Outside the maniacal gaze of Humbert, there is no nymphet. Lolita the nymphet exists only through the obsession that destroys Humbert.’ People were persuaded by Humbert’s dream, and now we have woken up. The sins of most predators catch up with them in the end. Meanwhile, there is now a defiance among teenage girls, a determination to own their sexuality, to act as they want and dress as they please. The prevalent view is that predation is not a female problem. There is no spectrum when it comes to sexual abuse and rape. The recent protests spurred by Sarah Everard’s murder attest to this – the slogan ‘No Means No’ sung out by crowds of teenage girls. A statement that makes clear their own agency; it bursts the bubble of male fantasy, slaps back at the predatory gaze.

I look again at Mann’s book At Twelve, at the young woman standing on the porch of the playhouse with her father behind her, and I see how everything in it is dwarfed: the miniature cups and saucers, the tables and chairs at her thighs. She is held back in her father’s possession, appropriated, denied the privacy of her natural evolution. In his unsafe embrace she is reminded only of her powerlessness, because the story is not yet hers. Mann’s portraits act as a caution, in capturing the adolescent girl who is too used to intruders. They warn us with the directness of her stare. But Mann also wants her to be more than her vulnerabilities. The girl in the photograph is spirited, remember, and, if she is lucky, she will learn to discover her power, free from the distortion of the predator’s gaze. These girls ask us to respect them. We might glance with curiosity and admiration at their beauty, but then we need to look away.