Thirty years ago, in the summer of 1991, I travelled to Denver to visit my graduate school mentor, Andy Sweet. I had received my doctorate in clinical psychology in 1989, and Andy had taught me most of what I knew about working with people suffering from the effects of trauma. As we sat in his backyard, Andy said: ‘You need to trust me on this, Debbie. There’s this new therapy called eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, EMDR for short, and it’s unique and potentially powerful.’ It looked and sounded wacky, but it was based on solid principles, and he was getting remarkable results. ‘I think that it’s going to change our field and bring relief to so many more trauma survivors. You should go and get trained in it … and you should run, not walk.’

So I did. I got trained in EMDR that year, studying with Francine Shapiro, its developer. She told us about her discovery four years earlier: she was walking in a park and found herself reflecting on some recent disturbing events in her life. As she thought about them, she became aware that her eyes were moving back and forth, left, right, left, right. And as her eyes moved, she was startled to realise that the negative emotional charge of her memories seemed to dissipate. She began to experiment, to explore the connection between ‘bilateral’ (left-right) eye movements and this ‘desensitisation’ of anxiety.

Shapiro developed a treatment procedure that asked patients to focus on the worst part of a traumatic memory while simultaneously watching her fingers move back and forth, left and right. In 1989, two years before my visit with Andy, she published the first EMDR controlled research study demonstrating the effectiveness of her method in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans and sexual assault survivors. Over time, clinical experimentation showed that other forms of bilateral stimulation (listening to tones alternating between each ear, or receiving alternating taps on the backs of one’s hands) basically worked as well.

And she had an exciting revelation: EMDR was more than a simple desensitisation strategy. Instead, it offered patients a chance to fully ‘reprocess’ their traumatic memories – to reconsider their experiences and come to fully know, feel, express and reflect on what previously had been too overwhelming to approach (let alone share with anyone else) and, in some cases, even too frightening to allow fully into their consciousness. I myself was astonished at how EMDR enabled my patients to seamlessly integrate other perspectives, including information that corrected misperceptions of the past, leading to spontaneous re-evaluations of their sense of worth, safety and control.

At the time of my introductory EMDR training, I was the clinical director of an inpatient psychiatric unit in southern New Hampshire treating women recovering from both acute and chronic trauma. Most had experienced horrible childhoods, with prolonged emotional, physical and sexual abuse and, as a result, were dealing with a range of psychiatric problems. Many had engaged in self-harm or had made attempts on their own lives. And most were struggling with hopelessness, unsure whether they’d ever be able to heal.

It was on this unit that I began using EMDR as a therapist. One of my first EMDR patients was Miriam, aged 23, who’d been extremely depressed, suicidal and unable to function for nearly two years following the loss of a pregnancy at eight months. In one unforgettable session, we used EMDR to target the moment when the doctor informed her that she’d lost her baby (coupled with the belief ‘I’m bad and don’t deserve to live’). As she processed the memory, she began to cry, accessing the grief that she’d buried deep inside. Miriam raged at God and at the boyfriend who’d left her after finding out that she was pregnant. And when she encountered a tidal wave of guilt, somehow blaming herself for ‘failing’ her baby, I asked her if, had the same thing happened to her best friend, she would have held her responsible or seen her as a failure too. She emphatically said: ‘Of course not! I would tell her that I understood her pain, and then I’d reassure her that she was not alone.’

Miriam continued to process, pausing and checking in after each 30- to 60-second set of eye movements, to respond to my question: ‘What do you notice now?’ As her eyes moved back and forth, I could sense the depression leaving her body and exiting my office. Her breathing relaxed and she sat up in her chair. After one more set of eye movements, she reported that she had spoken directly to her baby, in her mind’s eye, telling him how much she loved him and expressing sorrow about never having had the chance to hold him. When I invited her to imagine holding him in the present moment, she imagined cuddling and breastfeeding him, wrapping her arms in front of her as if holding a baby. She tearfully spoke of how she’d spent eight months dreaming about welcoming him into the world and then lost him.

Still new to EMDR, I feared that she was on the verge of plunging back into despair but I chose to trust the process. We continued with more sets of eye movements. And then, 50 minutes into our session, she once again sat up in her chair, and this time she actually smiled, the first smile I had ever seen on her face. Near the end of the session, when I asked her to think about the memory again, Miriam reported that her distress had moved, on a 0-10 scale, from a 9 to a 0. She said she could fully and completely endorse a new belief about herself – ‘It wasn’t my fault. I’m good and I have so much love to give.’ I had just experienced first-hand what my mentor Andy had described. I had witnessed transformation at warp speed.

EMDR was clearly more effective than ‘standard care’ in reducing the symptoms of PTSD

As I began to introduce more of my patients to EMDR, I saw similarly dramatic changes in the course of a week or even a single session. I had the privilege of bearing witness to their stories and accompanying them as they faced and resolved traumatic memories that had been haunting and harassing them for years. I watched them experience significant reductions in nightmares, flashbacks, depression, panic and suicidality. Over and over again, my patients reported a renewed sense of hope and possibility. Women new to the unit would hear about EMDR from other patients, and come to me saying: ‘I’ll have what she’s having!’

The most profound and lasting changes came as patients’ sense of self began to shift. They went from abject self-loathing to truly believing that they deserved to exist, that they were ‘good enough’ and ‘worthy of love’. Their nervous systems began to relax as they shifted out of states of hypervigilance, coming to deeply believe that ‘It’s truly over; I’m safe now.’ They began to see the world around them from an adult’s perspective rather than a child’s. I’d hear statements such as: ‘I see now that I have choices and I can take action.’ They began to move out of their isolation, saying: ‘I don’t have to be alone any more; there are other people like me; I matter and belong.’

What I was seeing in my small office on the Women’s Trauma and Dissociation Unit was soon reflected in published research studies – EMDR was an effective and efficient treatment for PTSD, significantly reducing or eliminating PTSD symptoms in as few as three 90-minute sessions in 85 per cent of sexual assault cases; and more than 75 per cent of traumatised combat veterans were free of PTSD in just 12 EMDR sessions. In yet another study, 100 per cent of single-trauma and 77 per cent of multiple-trauma survivors no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD after an average of just six and a half 50-minute EMDR sessions, demonstrating that EMDR was clearly more effective than ‘standard care’ in reducing the symptoms of PTSD.

To say that I was elated by my discovery of EMDR would be a major understatement. I’d been feeling so frustrated with the limitations of the treatment models previously at my disposal. Teaching patients a raft of cognitive-behavioural coping skills (positive self-talk, distraction, challenging distorted thinking) and helping them to manage their symptoms seemed necessary but not sufficient. They were typically able to achieve some degree of short-term relief but a ‘cure’ for their complicated symptoms and deep distress seemed elusive to them and to me. Memories associated with fear, shame and helplessness would continue to get reactivated, requiring ongoing efforts at top-down, cognitive self-management.

More traditional ‘talk therapy’ models lacked the focus and the clear path to healing that I was looking for. I was discouraged by the idea put forth in many of these models that treatment needed to be long-term, sometimes very long-term, to be effective. I had so many patients showing up at my door reporting that they’d already been in therapy for years, sometimes with many different therapists, and with little or no relief. This didn’t really surprise me. I had concluded early on in my clinical work that many of my patients were unable to find words to fully describe their traumatic experiences or their current state of being – at least not at first. They were often inhibited by shame or too terrified to speak or even unaware of why they were feeling the way they were feeling. Their traumas existed for them in images and physical sensations and as a ‘felt sense’ at their core, but there were no words to describe them.

I needed an approach that went beyond talk, one that guided my patients back to their bodies and emotional experiences without overwhelming or re-traumatising them. EMDR was that tool. Today, it remains my primary psychotherapy orientation. Its theory offers me a practical and encouraging lens through which to view my patients’ difficulties, and its protocols have provided me with a tried-and-true method for helping people transform their lives efficiently and profoundly, in ways that withstand the test of time.

So that you can fully appreciate the power of EMDR therapy, I want to explain it in a more granular way. EMDR is an integrative psychotherapy because it incorporates other approaches, from the free association of psychoanalysis to the bottom-up processing of the new mind-body and experiential techniques popular today.

It is also a comprehensive psychotherapy, most closely aligned with the trauma treatment introduced (some would say re-introduced) by the psychiatrist Judith Herman in her groundbreaking book Trauma and Recovery (1992). Herman’s model is known as ‘phase-oriented trauma treatment’ because of its three interrelated phases: promoting stability and safety, processing the trauma, and reconnecting with others. While EMDR also embraces the idea of phases, it offers its own distinctive set of procedures and uniquely features bilateral stimulation as the mechanism for change.

EMDR therapy emphasises the role of the brain’s information-processing system in a wide range of mental health problems. It’s guided by the adaptive information processing (AIP) model, which suggests that psychological difficulties result from a failure to adequately process traumatic memories to the point of ‘adaptive resolution’. Under ordinary circumstances, we easily process and resolve challenging experiences – we talk, dream or write about them, reflect on them, and learn from them by drawing connections with information that already exists in our brain’s neural circuits. Disturbances get ‘neutralised’ and ‘moved into the past’, allowing us to carry on with life – perhaps, with a bit more wisdom, a bit more resilience, and certainly less fear and anxiety.

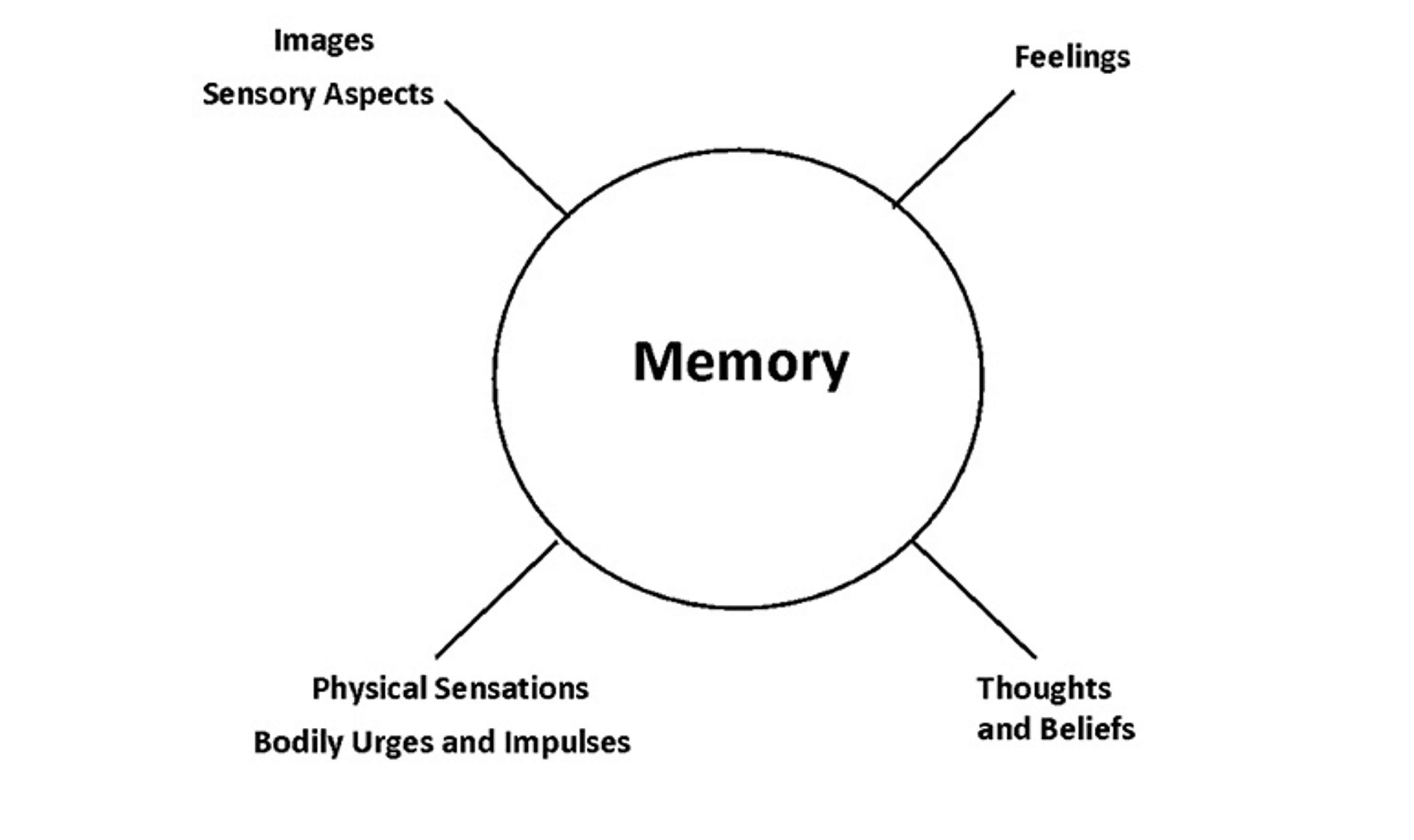

Figure 1. Components of experience

In overwhelming traumatic situations, normal, everyday information processing gets derailed. The traumatic memory, with all of its components – images and other sensory elements, emotions, physical sensations, impulses, thoughts and beliefs – gets ‘locked’ in the nervous system, unable to evolve or resolve. These inadequately processed memories lie in wait, getting reactivated, often unexpectedly, by internal or external ‘triggers’ – environmental or relational stressors, emotions, thoughts or sensory experiences such as sounds and smells – leading to painful psychological or body-based reactions. These might include intrusive images or flashbacks, anxiety or panic, hyper-reactivity or numbness, or feelings of shame. Patients might even experience extreme, out-of-the-blue negative reactions to seemingly benign situations, such as a friend not immediately returning a phonecall, or even positive events, such as receiving a compliment.

The brain returns to some kind of equilibrium, moving out of a perpetual ‘fight or flight’ or ‘shutdown’ mode

From the perspective of the AIP model, these out-of-proportion responses reflect a memory, locked in the brain at the time of some earlier trauma, that’s still throwing up red flags – days, months, years or even decades later. If the memory doesn’t get processed, there it remains, just beneath the surface – bearing influence, shaping decisions and reactions, and even interfering with one’s ability to function. As a result, people find themselves limited in their ability to respond adaptively to everyday challenges, still ‘stuck in the past’.

The AIP model argues that the brain’s information-processing system is no different than other body-based systems, such as the immune system; it’s functionally geared to prioritise survival and to move toward optimal health. When working properly, it operates like other systems in the body that spontaneously and reliably mobilise resources to heal a break or wound after an injury. In treating trauma, whether big or small, we’re treating an injured and malfunctioning brain.

Working from this perspective, the EMDR therapist strives to access memories associated with traumatic psychological injuries while simultaneously jumpstarting the brain’s stalled information-processing system. Bilateral stimulation, whether eye movements, tones or taps, is seen as the key to re-engaging that system, allowing it to desensitise and reprocess these trauma-based memories. The goal of EMDR is to help people fully process their traumatic memories so that they no longer cause symptoms and, ultimately, can be recalled without distress. In the end, the brain returns to some kind of equilibrium, moving out of a perpetual ‘fight or flight’ or ‘shutdown’ mode, and back into a more regulated state that permits more accurate thinking, more manageable emotions, and more relaxed and engaged social contact. As people unhook from the unsettling images, messages, beliefs, feelings and sensations associated with their traumatic memories, they’re suddenly able to think more calmly, clearly and creatively. They no longer feel compelled to respond in old, patterned ways. They no longer feel the need to withdraw from others, to avoid situations, to please everyone, or to dissociate from their everyday experiences. And they no longer need to turn to addictive, self-harming and unhealthy behaviours to soothe themselves and escape from pain.

As he was wrapping up his 14 months in treatment with me, John, who had been sexually abused by a childhood ‘family friend’, declared: ‘I finally feel like the “real me” has emerged. I’m not numb and hiding in a hole anymore, and I’m actually starting to understand what it means to feel fully alive and intimately connected to other human beings. I no longer see myself as bad or disgusting. And I trust that I’m ready to make good choices for myself.’ We celebrated his triumphant return to life together, with tears and tremendous joy.

Another client of mine, Katie, was a middle-aged, married woman with three adult children. Katie grew up in a family with a violent, verbally abusive, alcoholic father. Her mother, also a victim physically and verbally terrorised by her husband, regularly made excuses for his behaviour. Katie’s older brother unfortunately identified with his father, and often held Katie captive in their basement for hours, punching, berating and threatening her. She learned to survive by ‘leaving her body’ when things got bad, ignoring all of her own needs, never making waves, and focusing exclusively on trying to keep others happy. She used food to soothe her emotional pain, engaged in self-injurious cutting when food didn’t work, and struggled intensely with depression throughout her life. She developed significant digestive problems and high blood pressure. She described her nervous system as always on high alert, as she ‘waited for the next bomb to drop out of the sky’. When news outlets started reporting that immigrant children were being separated from their parents at the border and held in cages, she started experiencing intrusive images and nightmares about the aloneness and terror that she experienced as a child, and felt like she was ‘falling apart at the seams’. Katie had spent a lifetime holding her memories at bay, but now realised it was finally time to address them, and she came to me seeking help.

In EMDR therapy, we take a three-pronged approach to treatment, identifying and addressing past traumatic memories, present symptoms and triggers for distress, and goals for future functioning. Each of these becomes a target for processing. Before Katie and I could turn our attention to her traumatic past, we first needed to decrease her fear about facing the emotions and memories that she’d avoided for most of her life. We also had to deal with her concern that she would be unable to continue to function after opening the door to her past.

We did this by making sure that she had a good repertoire of skills and resources to help her stay ‘regulated enough’, securely grounded in the present and connected to me as we worked together. I explained that our goal was to help her maintain ‘dual attention’ – one foot always in the present while she gently dipped into the past. I suggested that she see herself as a passenger on a train, just watching the scenery go by, observing from a distance, not necessarily ‘reliving’ anything.

We also worked to strengthen her sense of safety and trust in our relationship; I reassured her that I would be there with her, moment by moment, as we addressed her past together. We then explored the connections between her reactions to current events in her life and various experiences in her childhood. Again and again, I would ask her to ‘float back’, following the current intrusive images, feelings and sensations she was experiencing to memories from her childhood. When she couldn’t identify earlier memories, we’d simply focus on current symptoms and triggers.

In each trauma-focused EMDR session, I’d help Katie ‘activate’ her memory by asking a standard set of questions, inviting her to identify the image, negative self-belief, emotions and sensations associated with our chosen target. We’d also identify what she’d prefer to believe about herself, setting a clear goal for the work ahead. Once the memory was activated, I’d introduce sets of bilateral stimulation, reminding Katie that there were no ‘supposed to’s and encouraging her to ‘just notice what comes up’ during each set, and to ‘let whatever happens happen’. After each set, I’d ask: ‘What’s coming up? What are you noticing?’ I might remind her that she was dealing with ‘old stuff’ or support her in expressing rage toward her perpetrator (out loud or in her imagination) or in offering comfort to her ‘younger self’. Processing would continue until the memory no longer carried any negative ‘charge’; at this point, I’d invite Katie to focus on her previously identified positive belief – the one she wanted to believe – and we’d continue processing until it felt completely true to her. We always left time to fully reorient to the present, to reflect on the experience, and to imagine tucking away, for the next time, any material that hadn’t been fully resolved.

EMDR was found to be the most cost-effective of the therapies evaluated

In the course of our treatment, Katie processed her terror and shame, feelings that she’d been carrying since childhood. She grieved for her ‘younger self’, recognising how alone and unprotected she’d been. She imagined bringing the young Katie into the present, soothing her, helping her to feel safe, and enveloping her in kindness and care. She imagined having supernatural strength and breaking free from her brother and her father as they pursued her. With every memory we processed, she reported feeling ‘lighter’ and more compassionate toward herself.

She discovered her ‘voice’ and, ultimately, found her own ‘real truth’ that was different from the watered-down, distorted story that she’d always told herself about her family of origin (‘it wasn’t that bad’) and current life (‘I have the ideal family now’). By the end of treatment, she was no longer depressed, and her PTSD symptoms were gone. She’d made new friends. Her physical health and daily self-care habits improved, and she started communicating differently with her husband and kids, expressing her needs and desires for the first time in her life.

Today, more than 30 randomised controlled trials substantiate the effectiveness of EMDR therapy for PTSD, taking the evidence far beyond anecdotal reports. Based on this research, EMDR therapy has been designated a top-tier, effective treatment for PTSD in the treatment guidelines of organisations around the world, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), and the US Department of Veterans Affairs and the US Department of Defense. EMDR does as well in the treatment of PTSD as other proven treatments, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy, but often in fewer sessions and without the hours of homework that CBT demands. A recent meta-analysis compared 11 trauma therapies recommended for the treatment of PTSD in adults; EMDR was found to be effective and also the most cost-effective of the therapies evaluated.

In 2007, I consulted on a study funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health that evaluated the benefits of eight sessions of EMDR therapy for the treatment of PTSD compared with a similar period on Prozac. I was initially worried that eight sessions would be just a drop in the bucket and wouldn’t make a significant difference for those who’d experienced trauma in both childhood and adulthood. I even worried that the treatment might stir up memories that couldn’t be dealt with in the time that we had.

So I was truly delighted when we found not only that subjects did well in the short run but that they continued to get better and better even after treatment stopped, as if their brains’ information-processing system had truly been brought back online. Even those with extensive childhood trauma saw considerable gains in the eight sessions; for this group, EMDR was ultimately superior to Prozac in reducing both PTSD symptoms and depression when symptoms started in adulthood. By the end of treatment, all of those in the EMDR group with adult-onset traumas had lost their PTSD diagnosis, along with three-quarters of those with childhood trauma histories. At follow-up six months later, 89 per cent of the childhood abuse survivors had lost their PTSD diagnosis, and a third were completely asymptomatic. Our results were published in the highly respected Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Thirty years ago, when I visited Andy in Denver, it was the eye-movement component that led him to describe EMDR as ‘kinda wacky’. Currently, more than 35 randomised controlled trials have been published that demonstrate the positive effects of eye movements. We can now unequivocally report that eye movements reduce negative emotions, imagery vividness and emotional arousal, while enhancing memory retrieval and flexible thinking, but why?

Among the hypotheses, researchers have shown that the eye movements in EMDR activate the parasympathetic nervous system, leading to a slowing of breathing and heart rate, and a reduction in arousal; others have shown that the eye movements compete with the recall of traumatic memories, making them less vivid and emotional; others still have suggested that the eye movements activate the same neurological processes that occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, when our most intense dreaming occurs, leading to less negative emotions, new associations between memories, increased cognitive flexibility, and improved insight.

Since Shapiro first took her walk in the park, a lot has changed in the practice of EMDR. It’s no longer regarded as a treatment for symptoms related just to discrete traumatic events. Neither is it viewed as applicable only in circumstances where the patient is dealing with the impact of ‘Big T’ traumas.

We now recognise that the definition of trauma needs to include the ‘little t’ traumas of everyday life – rejections, humiliations, failures and repeated, racially based microaggressions. Trauma might follow the loss of a job, the discovery of a partner’s infidelity, or a break-up or divorce. It’s often the larger context of an event – an individual’s autobiographical history and the reactions of others to the event – that determines whether a particular experience will lead to the development of PTSD or other significant mental health issues. We’ve also learned how to better prepare our patients for trauma-focused work, providing effective support to those who feel overwhelmed by present-day circumstances or particularly vulnerable and reluctant to address their complex trauma histories.

EMDR is now being used to treat people suffering from a range of disorders. It is no longer regarded as just a treatment for adults with identifiable traumas or those who meet strict criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD. There is mounting evidence supporting the use of EMDR therapy for the treatment of traumatised children, survivors of recent traumas, and those with complex post-traumatic stress disorder, most often diagnosed in patients with histories of prolonged and repeated trauma that started at an early age. And moving beyond obvious trauma-related disorders, there is now research that supports the use of EMDR with anxiety disorders, unipolar depression, pain, addictions, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychosis. EMDR is being used in inpatient and outpatient settings, medical hospitals, schools, prisons, the military, and in the field after major disasters and crises. After all, unprocessed trauma memories, still locked in the nervous system, can exacerbate, trigger or even cause many of these problems and disorders.

I tell all my patients: ‘I’m going to be with you every step of the way. I’m not going to let you drown’

And EMDR is being used to treat trauma resulting from neglect and deprivation. We now know that the consequences of childhood neglect, separation and emotional abuse – often referred to as attachment or developmental trauma – are usually more severe and far-reaching than those caused by other, more obvious and well-known forms of child abuse. Our therapy often targets the aloneness that survivors feel, as well as their belief that they simply don’t deserve to exist. We give them permission, as in Katie’s case, to imagine getting what they needed but never received or saying what they could never say to a perpetrator or someone who failed to protect them or act on their behalf. We invite them to step into their memory and acknowledge their ‘younger selves’, providing that much-needed, long-denied nurturance, comfort and validation. The healing that results can be profound.

Finally, EMDR is no longer regarded as a simple technique or protocol where therapists are encouraged to stay out of the way while the patient’s brain does the work; it has evolved into a comprehensive psychotherapy that emphasises the moment-to-moment attunement and collaboration, the relationship, between client and therapist. I tell all my patients: ‘I’m going to be with you every step of the way. I’m not going to let you drown.’ EMDR therapists strive to recognise and validate their patients’ wisdom, provide healthy perspectives, and keep them emotionally regulated during their sessions. We bear witness to their pain and meet them, again and again and again, with deep compassion, reminding them of their courage and strength, and helping them know that they’re not alone any more.

As I write this in the spring of 2021, the need for effective trauma treatment continues to grow. This has been a challenging time, with the COVID-19 pandemic, economic collapse, and both political and racial strife bringing trauma, adversity and loss to millions. In June 2020, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 40 per cent of adults in the US were reporting symptoms of depression or anxiety, a dramatic increase compared with the same period in 2019. During this time, my colleagues and I have been applying ‘early EMDR intervention’ protocols to effectively and efficiently treat first-responders and frontline workers, as well as those who have been on ventilators in the ICU and those who have suffered devastating losses of loved ones. For many with earlier trauma histories, such as my patient Katie, the stress, loneliness and grief brought on by pandemic-related upheavals have unearthed memories of previous suffering that we’ve needed to address too. But despite the daunting mental health picture we face, I remain deeply hopeful.

I feel excited and encouraged by the results that I consistently get with EMDR therapy. I’m inspired by all we continue to learn through research and clinical innovation. And I’m grateful to be part of a resilient and dedicated professional community committed to making a difference in the world.

For some, recovery is swift and EMDR truly seems like a too-good-to-be-true, miracle cure. For others, particularly those with complex trauma histories and neverending present-day challenges, the road is often harder and sometimes much longer. That said, I feel solidly optimistic and regularly say to all of my patients: ‘You are hurting, but you can recover and it’s not going to take a lifetime.’

To read more about trauma therapies, visit Psyche, a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophical understanding and the arts.