One way to avoid disillusionment is to stay at home, another is to fortify your illusions until they are unassailable. When D H Lawrence went to Sardinia in 1921 it was ostensibly ‘to see if I should like to live there’. The idea had come to him the previous year: to travel from one Italian island – Sicily, where he was living in Taormina – to another. The resulting book, Sea and Sardinia, published later that year, stands as a strangely luminous landmark in the history of travel writing. No book has made me think more deeply, more uncomfortably, about the impertinence of describing a place that is not your home – about what is owed to your subject, and what is owed to your reader, and about whether those twin obligations can ever be reconciled.

D H Lawrence photographed by Elliott & Fry, c1915. Photo courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

Lawrence makes me think of one of those kinetic watches – movement itself made him tick. Between the armistice of 1918 and his death 12 years later he rarely settled for long, even if his life continued to circle particular centres of gravity – Sicily, New Mexico, Germany. He wrote four books that can, with some liberty, be described as travel writing, appearing at roughly five-year intervals: Twilight in Italy in 1916, Sea and Sardinia in 1921, Mornings in Mexico in 1927, and Sketches of Etruscan Places, published unfinished, two years after his death, in 1932.

Mornings in Mexico, the last travel book he saw published, begins with a mature traveller’s insight: ‘We talk so grandly, in capital letters, about Morning in Mexico. All it amounts to is one little individual looking at a bit of sky and trees, then looking down at the page of his exercise book.’ Few travel writers have so guiltlessly delighted in their own subjectivity, and nowhere is Lawrence’s delight more evident than in Sea and Sardinia. He perceives the island with a clarity that electrifies him, like a person with new glasses, a new hearing aid, newly in love. It is the book – at least among his nonfiction – in which he allows himself to be most visible to his readers. Visible at the expense of the place itself, it’s true. Visible to the extent you sometimes want to look away.

Lawrence’s birthland, a prison of ‘moral judgment and condemnation and reservation’, was never going to contain him, but his first foray beyond Britain did not take place until May 1912, when he was 26. With Frieda Weekley, the German wife of his former language tutor, he absconded to Germany – Metz, Waldbröl, Munich, Mayrhofen, Breuberg. Then in August, over the Alps to Gargnano, Italy: a ‘rather tumble-downish place on the lake [Garda]’, he wrote to his friend, the critic Edward Garnett. ‘I shall live abroad I think forever.’ And by and large he would.

In Gargnago he wrote with an energy remarkable even by his volcanic standards: two plays, the end of Sons and Lovers (published in 1913), the start of The Rainbow (1915), and the essays that would become Twilight in Italy. He loved Gargnano and the water, could indeed have stayed forever – but then, as quickly as he fell in love with it, he found the place unbearable. This was the travel pattern, for Lawrence, enchantment always a preface to disenchantment. ‘Travel seems to me a splendid lesson in disillusion,’ he told his friend the actress Mary Cannan. To yet another friend, Earl Brewster, he was blunter: ‘Don’t have ideas about places, just because you’re not in them. All places are tough and terrestrial.’ He dreaded familiarity, and could feel it coming on. He always wanted to feel as if he had just jumped off the train. His life, as a result, was a cycle of alighting followed by decamping. Not that he seemed to find this exhausting, not at all.

Returning to England at the outbreak of war was like being recalled from bail. In 1915, broke and sick and craving solitude, he moved, with Frieda, to a remote village in Cornwall. Lawrence and his German wife were unlikely ever to be welcomed. Their new neighbours observed that the writer, who was apparently too weak to bear arms, was robust enough to rake his garden. In late 1917, their cottage was turned over by the local police and they were essentially deported back to London, on suspicion, ludicrously, of spying for Germany.

When in doubt, move. Where, was always the question

With peace came freedom to abandon hopeless, ruined England for what he would call his ‘savage pilgrimage’. If Lawrence’s travels were a pursuit, they were also a flight from all the war represented. This he had in common with many of his British contemporaries, who were equally eager to be gone once borders reopened; unlike most of them, however, Lawrence wasn’t a tourist, in so far as he never really came back. Any centripetal force England had once exerted upon him had been sapped. He was free.

First, back to Italy, then: Florence, Picinisco, Capri and, on 8 March 1920, the top floor of a villa, Fontana Vecchia, in Taormina on Sicily’s Ionian coast: stillness. ‘Pink gladioli, and pink snapdragons, and orchids.’ A desk, vast views across the Strait of Messina. ‘Living in Sicily after the war years was like coming to life again,’ Frieda would recall. And so, for a while, Fontana Vecchia became a new centre – somewhere to light out from, somewhere to return to. ‘I like this place more than any other,’ he wrote. He felt he had lived there for 100,000 years. ‘Lascia mi stare.’ Let me be.

But by October he was writing to fellow writer Catherine Carswell: ‘I shan’t stay in Taormina, I think – perhaps go to Germany for the summer, perhaps to Sardinia.’ To Cannan, two months later: ‘I am cogitating whether to take this house for another year, or whether to retire to the wilds of Sardinia. Which?’ Which, or rather where, was always the question. For just as he had tired of an earlier Italian island, Capri, now he was tiring of Sicily, and of Taormina, a town populated, he insisted, by ‘the most stupid people on earth’, not excluding his fellow English expats ‘cultivating their egos hard, one against the other’.

When in doubt, move. In a book review, written in 1926, he suggested that all travel is undertaken ‘with a secret and absurd hope of setting foot on the Hesperides, of running our boat up a little creek and landing in the Garden of Eden. This hope’ – of course – ‘is always defeated.’

Sardinia (Ital. Sardegna, Greek Sardo), situated between 38° 51’ and 41° 15’ N latitude and separated from Corsica by the Strait of Bonifacio (7½ M wide), is, next to Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean. Its length from N to S is 166 M, its breadth from E to W 89 M …

– from Baedeker’s Southern Italy and Sicily (16th ed, 1912)

Lawrence and Frieda were on the island for barely five days in total in January 1921, travelling by steam train and post bus from Cagliari in the south to modern-day Olbia on the northeastern coast, a journey of around 150 miles. He took no notebook, but did pack a copy of Baedeker’s Southern Italy and Sicily, with Excursions to Sardinia, Malta, and Corfu. The 16th edition, published nine years earlier, goes on to tell us that the ‘Sardinian character is grave and dignified compared with that of the vivacious Italians, and they are noted for their chivalric sense of honour and their hospitality.’ Sardinia, then, was not Italy: this was part of the island’s promise for Lawrence, and not just because he’d had it with ‘the most stupid people on earth’.

In fact, his preconceptions fixed long before leaving Fontana Vecchia, he would find little in Sardinia that he had not planned to find – that was not preformed inside himself. ‘Sardinia, which is like nowhere. Sardinia, which has no history, no date, no race, no offering. Let it be Sardinia.’ A destination, finally: the Garden of Eden. ‘It lies outside; outside the circuit of civilisation.’ He only needed to open that little book, with its red leatherette cover, to learn about the incursions ‘civilisation’ had made into the island’s long story.

At the same time, he did believe what he said: a place might exist that had been spared all that Europe had subjected itself to, and not just the war – all of it, right back to when ‘the mentality of Greece appeared in the world’! He would go looking for that realm and perhaps, if we take him at his word, make it his home. And so he set off with Frieda – ‘the q-b’, as she is called in Sea and Sardinia: queen bee. On the ‘fourth day of the year 1921’, they travelled by train from Catania to Palermo, where they boarded the steamer for the Sardinian capital of Cagliari. We get a clue as to what he was really looking for before their steamer even reaches Sardinia: ‘I wished in my soul the voyage might last for ever, that the sea had no end’; and later: ‘Ah if one could sail for ever … Not to be clogged to the land any more.’ Finally, they reached Cagliari on Thursday 6 January, which from afar, Lawrence noted, has a ‘curious look, as if it could be seen, but not entered’.

He never ceased to believe that travel could liberate one from time

In a sense, the city remained inaccessible to him. ‘We climb a broad flight of steps, always upwards, up the wide, precipitous, dreary boulevard with sprouts of trees.’ ‘Strange, stony’ Cagliari; ‘dreary’ Cagliari. Dreary again and again, very Lawrentian. ‘The Cathedral must have been a fine old pagan stone fortress once. Now it has come, as it were, through the mincing machine of the ages, and oozed out baroque and sausagey.’ When ‘history’ was unignorable it stood only for a kind of cultural mongrelisation to be deplored. ‘For the rest I am not Baedeker.’ True. Was it just that he was hungry?

‘If one travels one eats,’ he writes, and Sea and Sardinia can be seen as a kind of culinary diary, albeit one in which food is a pretext to indulge his disgust – from the ‘massive yellow omelette, like some log of bilious wood’ on the voyage over, to the ‘strong boiled cauliflower’ in Sorgono, ‘which one ate, with the coarse bread, out of sheer hunger’. The further north he goes, deeper into the island, the thinner the broth will get, the harder the bread and the more impertinent the service. Lawrence, of course, relishes every mouthful, every resentful ‘beldame’ slamming down a plate before him.

As for Cagliari, what delights him is not the cattedrale di Santa Maria di Castello, or the piazza Costituzione, or the bastione di Saint Remy; but the vegetable market – stuff that would soon go off, which was perhaps the point. It was the instant that detained him always, travel not as a fluid progression but as a series of impressions. No wonder he considered calling the book ‘Sardinian Films’, as if the journey were built of umpteen freeze-frames.

But he will not find what he is seeking in mongrel Cagliari, however hard he looks. There was no such thing as flight from oneself – Cornwall had taught him that; but he never ceased to believe that travel could liberate one from time. To maintain this belief, in the face of all time’s relics, it was necessary to pack blinkers, alongside your camping stove and sun hat. ‘When one walks, one must travel west or south,’ he insists, absurdly, in Twilight in Italy. ‘If one turns northward or eastward it is like walking down a cul-de-sac.’

But that afternoon, a day after they arrived in Cagliari: north. ‘En route again.’

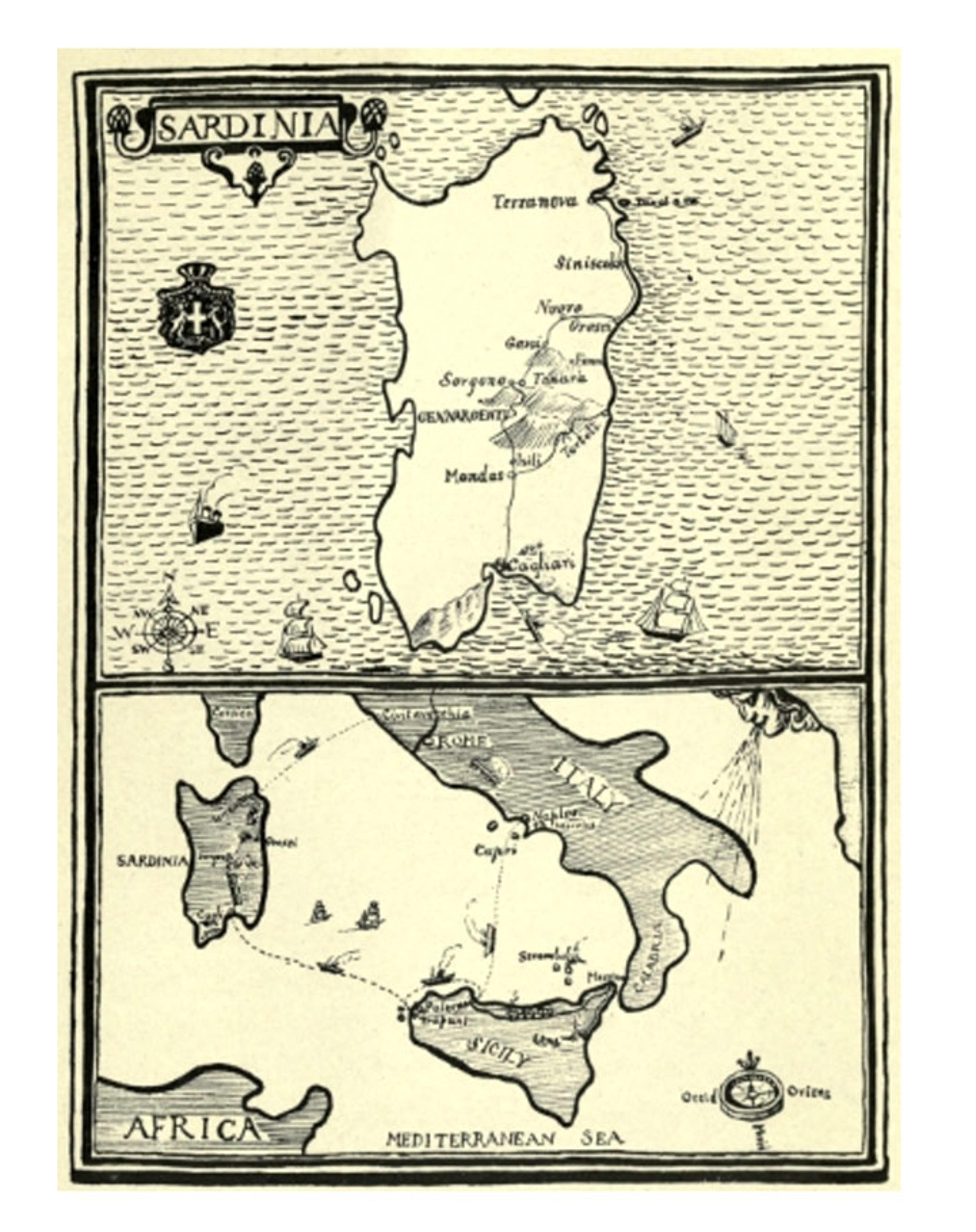

The only places labelled on the simple map that Lawrence drew to accompany his book are those they passed through: the island existed only in so far as he witnessed it. The line of their journey is a snail’s trail, then, but also a capital ‘I’, tracing the ‘narrow-gauge secondary railway that pierces the centre’.

Lawrence’s original hand-drawn map from Sea and Sardinia. Public domain

From the window of the third-class carriage from Cagliari that afternoon he gets his first sight of his imagined Sardinia. What he sees is England; specifically Cornwall, that hard little corner of the country that rejected him back in 1917. Three times in four paragraphs he describes the scene from the train window as ‘moor-like’, and then: ‘almost Celtic’. In his scrabbling for an analogue, I’m reminded of the British explorer Harry St John Philby, who described the towering red sand dunes of the Arabian Empty Quarter as ‘downs’. Even Lawrence had only so much experience, and so much language, to bring to bear on the unfamiliar.

The emblematic image of his movement across the island is the figure in the landscape, ‘small but vivid black-and-white, working alone, as if eternally … All the strange magic of Sardinia is in this sight.’ Nothing pleases him more than this ant personage, far off, and therefore not really a human, the Sardinian peasant in his traditional outfit, bent to the land. He represents everything Lawrence had expected to find here: manliness, individuality, multifariousness, a peasantry that knows its place and can imagine no other. Yet the black-and-white ‘lord of toil’, like a figure in a painting, is always too distant to have its own voice. Lawrence can continue to imagine a pure endemic sensibility that has somehow been conserved, like the relic dinosaurs of Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Lost World (1912).

Baedeker will be honest: ‘The inns, except in Cagliari, Sassari, and Macomer, are very mediocre, and away from the railways are sometimes quite intolerable.’ The hilltop town of Mandas, naturally, was like Cornwall or Derbyshire or ‘a part of Ireland’, as far as Lawrence was concerned. The landscape was ‘far more moving, disturbing than the lovely glamour of Italy and Greece. Before the curtains of history lifted, one feels the world was like this.’ But as a large Mediterranean island, Sardinia had never been excluded from history’s theatre, as both crossroads and entrepôt. For the Romans, it had been a kind of penal colony to which it shipped criminals and dissidents. Invasion after invasion followed, with successive occupations: Vandals, Goths, Greeks, Arabs, Pisans, Genoese, Aragonese, Austrians. This deep past of colonialism, of invasion and resistance – Sardinian history, that is – instilled in its populace what the Sardinia-born historian Maria Giacobbe, in Diario di una maestrina (‘Diary of a School Mistress’, 1957), calls ‘a deep mistrust of the consequences that European affairs would have on them’. Active resistance settled into a ‘rooted apoliticalness, a dark sense of extraneity, of nonparticipation’.

But if Sardinians had once been able to consider themselves somehow extraneous, any such illusion had been dispelled by a war in which, fighting under the flag of Italy, no fewer than 2,164 members of the Sardinian Sassari Brigade had been killed. In 1921, as Lawrence and the q-b rattled north into the mountains, ‘history’ was as busy as ever. Formed by survivors of the Sassari Brigade, the nationalist Sardinian Action Party, under the banner of national autonomy, would win 36 per cent of the vote on the island later that year. Unseen by Lawrence, Sardinia was continuing to change. That distant figure in black and white was absorbed with the wider world as well as the soil at his feet.

In Mandas, Lawrence and Frieda dine with three ‘soup-swilkering’ railway officials, and are informed that ‘at Mandas one does nothing. At Mandas one goes to bed when it’s dark, like a chicken.’ After a single night, they continue by train into the mountain interior, transferring to a rattling post bus at Tonara, thence to Gavoi, Nuoro, Orosei, and – just five days after arriving on the island – Terranova (since renamed Olbia) and the steamer back to the mainland. In Nuoro, as in Mandas, ‘[t]here is nothing to see … which, to tell the truth, is always a relief.’ This of course was in keeping with his vision of the island as a whole: he did not wish to dwell on any relics that would anchor it in time – neither the neoclassical duomo or the church of Santa Maria della Solitúdine. ‘Happy is the town that has nothing to show.’ And happy the writer unworried by any sense of duty to his subject. Well, nominally his subject.

For Lawrence, travel’s value lay in finding himself an alien

A different kind of writer, more diligent, more dutiful, would have apportioned the time not spent travelling to actually writing up the journey, or at least reading some books about the island. But such a reflective approach would be antithetical to the spirit that inspired Sea and Sardinia. He was not Baedeker, and didn’t care what anyone else made of the place. The moment he got back to Fontana Vecchia, a few days later, he went to work, like a mine truck dumping its ore at a smelter.

Meanwhile he was excitedly scribbling letters to friends in England: ‘We made a dash to Sardinia’; ‘We went to Sardinia – such a dash’; ‘a little dash to Sardinia’; and on 12 February: ‘I have nearly done a little travel-book.’ Barely a month after leaving, he had finished dashing off a book. He’d thought of calling it ‘Diary of a Trip to Sardinia’, but told his agent: ‘Use what title you like:’

– A Moment of Sardinia

A Swoop on Sardinia

A Dash through Sardinia

Sardinian Films or

Film of Sicily and Sardinia

– the ‘Diary’ title was merely provisional.

As Paul Fussell points out in Abroad (1980) – his study of British travel writing between the wars – Lawrence’s first travel book, Twilight in Italy, carries in its title an idea of reconciliation: as Lawrence puts it, between ‘sun and darkness, day and night, spirit and senses’. ‘Where, then,’ he asks, ‘is the meeting-point?’ Where. Was that the cause of his skittishness? ‘Comes over one an absolute necessity to move,’ reads the first line of Sea and Sardinia. During the following decade, it would overcome him again and again, compelling him to Sri Lanka, Australia, New Zealand, Rarotonga, Tahiti, the United States, Mexico, Germany, France, Italy, Scotland, Austria, Switzerland, Italy once more; and finally, after a stint at the sanatorium in Vence, on the French Riviera, on 2 March 1930, an end to motion. (An end, though the sanatorium’s name cannot have escaped him: Ad Astra, ‘to the stars’.)

In his last travel book, Mornings in Mexico, published 11 years after his first, Lawrence’s insistence on difference – difference that lies far below the superficies of ‘culture’ – curdled into something desolating: ‘Our way of consciousness is different from and fatal to the Indian. The two ways, the two streams are never to be united. They are not even to be reconciled. There is no bridge, no canal of connexion.’ Once, he had gone out in search of that bridge or canal – that ‘twilight’; now, his blinkers had narrowed to a chink. ‘To pretend that all is one stream is to cause chaos and nullity.’

Since his final departure, the trajectory of travel writing as a genre (in so far as it can be called a genre) has, thankfully, tended in the opposite direction. The travel writer Jan Morris, who was Lawrence’s antithesis in her erudition, suggested in a 1997 interview with The Paris Review that travel itself might contribute to precisely what Lawrence repudiated: that it might be ‘a quest for unity, a search for wholeness’. If, for Lawrence, travel’s value lay in finding himself an alien, for Morris, it lay in recognising herself, again and again, in the face of the stranger. These approaches are not, themselves, irreconcilable.

In a tribute written after Lawrence’s death, Rebecca West recalled a trip she and the writer Norman Douglas made in 1921 to visit him in Florence (where Lawrence was staying, true to form, in a ‘poorish hotel’ overlooking ‘a trench of drab and turbid water’). ‘Douglas,’ she writes, ‘had described how on arriving in a town Lawrence used to go straight from the railway station to his hotel and immediately sit down and hammer out articles about the place, vehemently and exhaustively describing the temperament of the people.’ And when the pair found him, what was he doing but precisely that, ‘pounding out articles on the momentary state of Florence with nothing more to go on than a glimpse of it’? If it seemed to West ‘obviously a silly thing to do’, she later came to appreciate his method: ‘I was naive. I know now that he was writing about the state of his own soul at that moment.’

His description of his soul as it was during those five days on Sardinia was not universally celebrated back in England, and didn’t sell. The novelist and critic Francis Hackett conceded it was ‘beautiful’ but objected to its ‘mid-Victorian gush’; only when its author ‘lifts us over his grinding account of his own temperament,’ he complains, do ‘we have a superb chance to enjoy Sardinia’. But do we, even then? There’s not much ‘escapism’ to be gleaned from Sea and Sardinia, unless you find liberation in being crammed into the mind of David Herbert Lawrence. To suggest, as Anthony Burgess did, that he somehow ‘extracted the very essence of the island and its people’ in those few hurried days is hubristic, but also misses the book’s point. As West correctly understood, the essence Lawrence was interested in extracting was his own. When he suggested that Sardinia was ‘like nowhere’, he didn’t mean unlike anywhere else. He was imagining a place beyond the reach of maps. What is remarkable is that, less than two years later, he found it, not in the Old World but the New.

In 1921 a wealthy American heiress named Mabel Dodge Sterne, who had been dazzled by Sea and Sardinia and believed that only its author was capable of describing the landscape of New Mexico, invited Lawrence and Frieda to stay at her ranch near Taos. Lawrence was ravished by the desert’s ‘pure and overweening’ light, as every newcomer is. ‘[F]or a greatness of beauty I have never experienced anything like New Mexico.’ He believed he had found it, that which had eluded him in Sardinia: not just isolation, which was cheap, but a set of coordinates that stood apart from time. It ‘was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had,’ he wrote. ‘New Mexico … liberated me from the present era of civilisation.’