[B]ecause it is very easy for the writing of a Black man or a West Indian to be admired for the wrong reasons.

– from ‘A Tribute to C L R James’ by Derek Walcott in C L R James: His Intellectual Legacies (1994)

In late 1949, the West Indian intellectual C L R James sat down in his residence in Compton, California and, in a burst of creative energy, composed what turned out to be a frightfully prophetic analysis of the historical fate of democracy in the United States. Titled ‘Notes on American Civilization’, the piece was a thick prospectus for a slim book (never started) in which James promised to show how the failed historical promise of its unbridled liberalism had prepared the contemporary republic for a variant of totalitarian rule. ‘I trace as carefully as I can the forces making for totalitarianism in modern American life,’ explained the then little-known radical. ‘I relate them very carefully to the degradation of human personality under Hitler and under Stalin.’

C L R James in 1938. Courtesy Wikipedia

At the climactic centre of this ominous analysis was the contemporary entertainment industry, which, James argued, set the stage for a totalitarian turn through its projections of fictional heroic gangsters as well as its production of celebrities as real-life heroes. A manufactured Hollywood heroism, he warned, had the potential to cross over from popular culture to political rule. ‘By carefully observing the trends in modern popular art, and the responses of the people, we can see the tendencies which explode into the monstrous caricatures of human existence which appear under totalitarianism.’ Completed in early 1950, James’s proposal remained underground for decades until it found publication under the abbreviated title American Civilization in 1993. Four years earlier, the author had passed on into history as one of the finest minds of the 20th century.

Given the din of bookish discussion about the spectacular antidemocratic turn in US politics in recent years, one would expect mention of American Civilization somewhere alongside, say, the work of the Frankfurt School. James, after all, stands today as one of the most renowned, even revered, thinkers in the North Atlantic. A novelist, journalist, pamphleteer, philosopher, Marxist theoretician and, in the words of V S Naipaul, ‘impresario of revolution’, this West Indian has acquired a posthumous stature in the West that would stun most people in the region where he was born in 1901. James is to the world of critical intellect as Brian Charles Lara is to the world of cricket – to use an apt analogy. His obituary in the The Times of London employed the sobriquet ‘Black Plato’. And, within a year of his death, The C L R James Journal was established in his name. In the ensuing decades, there has been an outpouring of books, anthologies and articles about his life and work, the vast majority coming out of the United Kingdom and the US, where James spent most of his mature years. A veritable ‘Jamesian industry’ now thrives in the 21st-century North Atlantic. Yet, for all this First-Worldly industriousness, or maybe because of it, James’s analysis of totalitarianism in American Civilization remains ignored.

At the base of this ignorance is a 30-year-old tale of radical misreading. Beginning in the 1990s, commentaries on American Civilization have erased its concern with the dark cultural politics of totalitarianism, dismissing the manuscript as quixotic and optimistic, even embarrassingly romantic. James, according to reviewers, fell for the US with the naive zeal of what Trinidadians would call a never-see-come-see. This radical was so dazzled by the North American republic that his radicalism disappeared once he sat down to write about its history and culture. In American Civilization, James was ‘enthusing with the greatest passion about the democratic capacity of the civilization with which he had fallen in love,’ the UK-based historian Bill Schwarz wrote. In a review for The New Yorker, Paul Berman concurred, describing the work as proof that ‘James basically loved the United States’. Yet, far from love and happiness, the manuscript was inspired, we will see, by a concern with the despair and hopelessness of US citizens and by a worry about the political portent of these mass feelings.

James’s basic contention in American Civilization was that a critical mass of the population had become so desperately distressed by the failure of the promises of liberal democracy that they were prepared to give up on it and elect, instead, to live vicariously through violently amoral political heroes. ‘The great masses of the American people no longer fear power,’ wrote James near the end of the manuscript. ‘They are ready to allocate today power to anyone who seems ready to do their bidding.’ This popular disenchantment with liberalism and the accompanying vulnerability to totalitarian leadership manifested in the entertainment industry, according to James. In films, novels, magazines and comics, he identified a contemporary archive of the cultural politics of totalitarianism – not a source of special affection for the modern republic (James actually trashed much of US popular culture as ‘ephemeral vulgarity on a colossal scale’). For him, moreover, the dire US situation was not exceptional but simply a richer symptomatic case of a modern derangement. The conceit that James was seduced by the achievements of ‘American civilisation’ is one of those strange North Atlantic fictions; one that reveals more about those who study James than about James himself.

Cyril Lionel Robert James led a wonderfully itinerant life. A British colonial, ‘Nello’, as intimates called him, was raised in the town of Tunapuna on the eastern edge of Trinidad’s capital of Port of Spain. James would go on to live in many places over the next eight decades but would never settle in any one. He was a man ‘on the run’, as his fellow Trinidadian Naipaul put it in his thinly veiled fictional sketch of James in A Way in the World (1994). Or, maybe James said it best with regard to his record of endless movement: ‘I have no conception of home,’ he told Alan Warhaftig for the Los Angeles Review of Books. ‘My home is where I find myself most happy in the political work that I’m doing.’

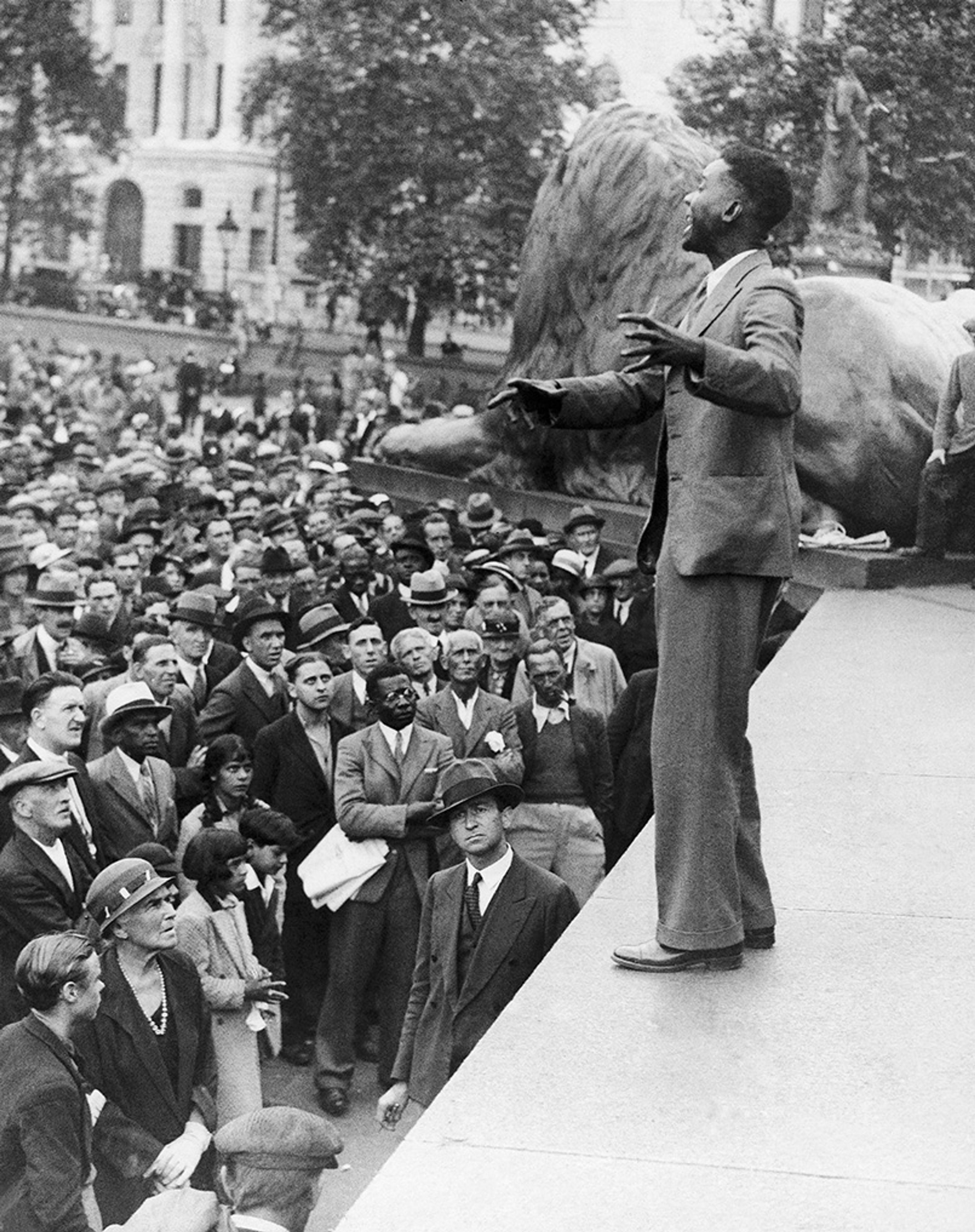

C L R James denouncing Benito Mussolini’s intention to invade Abyssinia (later Ethiopia) in Trafalgar Square, London in 1935. Photo by Keystone/Getty

James’s history of happy homelessness began in 1932 when, as a young modern renaissance man with writerly gifts and ambitions, he left Trinidad for Lancashire, England before moving to London the following year. The colony was not enough for his rebellious, restless intellect. Already a local legend as a debater and littérateur, the confidently self-educated James flourished in the metropole. In just over five years, he established himself as an adept cricket journalist, a charismatic public speaker and a well-regarded author on the anticolonial, Trotskyite scene. By 1938, James had a few books under his belt, including the novel Minty Alley (1936), World Revolution, 1917-1936: The Rise and Fall of the Communist International (1937), and the now classic The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (1938). Indeed, it was his obvious facility as a persuasive mouthpiece of Marxist views that got James invited to the US on a speaking tour later that year – ‘born to talk’ is how Naipaul described him. He had planned to spend only a few months in a republic that he once described as ‘dreadful’, intending to return to England in time for the following cricket season. James wound up in North America for the next 15 eventful years.

James proposed a book about how US liberal society could degenerate into a totalitarian one

It was a sojourn that he would recall as the most fertile episode of his intellectual career. Improvising a life that took on new expansive dimensions, James travelled across the continent, including Mexico, where he met – now famously – with Leon Trotsky. As part of his increasingly radical political work, James also studied and taught himself philosophy in concert with Raya Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee Boggs, mastering, in particular, the dense dialectics of G W F Hegel. Personally, and perhaps most notoriously, James fell in love with a young California-born creative and activist named Constance Webb, who became his second wife. By 1949, they had a son, Nobbie. It was around this time that James produced ‘Notes on American Civilization’, the lengthy proposal for a shortish book about how this liberal society could degenerate into a totalitarian one.

Before he could begin the proposed work, however, the wedded US forces of McCarthyism and immigration law landed James in an Ellis Island detention centre (doubts about the validity of his divorce from his first wife in Trinidad were used to undermine the legal status of his marriage to Webb). From a cell in 1952, James authored a book-length take-off from his proposal, a literary study that elaborated the significance of the totalitarian theme in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851). Titled Mariners, Renegades and Castaways, it was published in the following year. A few months later, James chose to return to London rather than be deported. His proposal for a work on ‘American civilisation’ languished, remaining virtually unknown until 1983, when the historian Robert Hill rediscovered one of the seven circulated copies (the one belonging to James’s colleague, the activist and scholar Nettie Kravitz).

Back in England, James gradually turned away from his Americanist scholarly concerns and in the late 1950s focused his writerly attention on a cultural history of cricket told from an autobiographical angle. Published as Beyond a Boundary in 1963, this piece of literature sealed the author’s place within the world of British letters. In that same year, too (in an exquisite irony appropriate for James), a second edition of Black Jacobins was published, assuring the author’s place in the annals of the Black radical intellectual tradition. From then until his death, the increasingly eminent James made London not so much a home as a base for his travels, which included visits to Africa, a return to the US in 1968 to teach, and a final trip to Tunapuna two decades later to be buried.

James’s prolific, peripatetic 20th-century life is well captured in a lively biography by John L Williams, C L R James: A Life Beyond the Boundaries (2022). This rendition of James stands out for its willingness to dwell in the creases of the protagonist’s private life, and the result is an image of the man that is fresh for its fleshiness. To a degree before unseen, the James that we have become used to regarding as a philosophical genius is featured in this book as vulnerable and very human, especially during his years in the US. Williams casts ‘Jimmy’, as the American James was known, as a seducer, a philanderer and, above all, a domestic failure. Readers discover, for example, that the middle-aged James, after finally catching Webb, whom he had passionately pursued for nearly a decade, suffers from bouts of impotence. Williams respects James’s intellectual accomplishments, but his account hardly conceals a doubtful judgment of James the man, especially the American incarnation, as a jejune dreamer, a rebel with an unrealistic cause. The sum effect is a biography that appealingly humanises a man too often heroised, and there’s a good chance that C L R James: A Life Beyond the Boundaries becomes the biographical standard.

For this reason, it is important to highlight that Williams reinforces the erasure of the concern with totalitarianism in American Civilization. He, too, dismisses this text as a somewhat embarrassing romantic detour, treating James as something of an America groupie rather than the serious Americanist ethnographer James intended to be. In Williams’s view, American Civilization was an expression of the author’s generally unhinged ideas about the US, including the belief that ‘America was on the brink of revolution’. Despite not ‘denying the brilliance of many of the insights’, Williams finds the work to be formless, unfinished and fundamentally flawed. That James failed to secure a contemporary publisher does not surprise him. In fact, like many other critics, Williams feels compelled to rationalise the manuscript, echoing the common tendency to explain it as a product of convenience if not desperation. James’s text was a tactical plea to remain in the US legally, with his comrades and newly formed family, according to Williams. American Civilization, he suggests, was effectively a praise song for a green card.

If this piece of writing was praise, we can only wonder what condemnation would sound like. Here was a terrifying critique of US society through its mass culture, containing an analysis resonant with the views of Frankfurt School critics like Theodor Adorno, with whom James met in New York in the 1940s. Indeed, American Civilization reminds us that James’s geopolitics presumed a humbling historical regard for the republic. He wrote unimpressed by the Cold War triadic view of the planet, imagining the North American nation as part of not the First World but the New World. In James’s historical imagination, the US was an unexceptional product of European colonialism, a point he made frankly in Beyond a Boundary:

[F]rom the first day of my stay in the United States to the last I never made the mistake that so many otherwise intelligent Europeans make of trying to fit that country into European standards. Perhaps for one reason, because of my colonial background, I always saw it for what it was and not for what I thought it ought to be. I took in my stride the cruelties and anomalies that shocked me and the immense vitality, generosity and audacity of those strange people.

This effectively postcolonial view, lost on commentators who encountered the document in the wake of the Cold War, is essential to the argument in American Civilization.

James’s text rooted the vulnerability of the US to totalitarian rule in its history of European colonialism, specifically in its British inheritance of liberal political culture. The import of this colonial legacy appeared early. ‘Ideologically,’ he explained in the first chapter, ‘the European past hangs over the country. Jefferson is the product of Locke.’ But the issue for James was not simply the derivativeness of North American liberal ideology; it was the deviance, the extravagant difference from what obtained in the metropole. According to him, a peculiarly passionate investment in British liberalism prevailed in the colonies and the subsequent republic. In North America, the concept of ‘free individuality’ flourished with an uninhibited and consensual character unknown in Europe, making for a political culture that was unphilosophical, unreflective, resistant to probing the intellectual premises of its dominant liberal ideology. Instructive in this regard was the Jacksonian era (c1820s-50s), argued James, who viewed the period as one in which the issues of liberal politics were worked out not in speculative theory (as was happening in Europe) but through violent practice. This romantic quality of hegemonic US liberalism was foundational to the analysis in American Civilization, for the temptation to turn toward antidemocratic politics, James contended, was a product of the failure of the nationalist romance with free individuality.

By the mid-20th century, hope in the idea of Americanism as heroic individual freedom was exhausted

James’s argument about the hyper-individualistic and anti-intellectual way of liberal life in the US explains his heavy and explicit debt to Democracy in America (1835, 1840), the 19th-century classic by the French political sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville. In conceiving the republic’s history, he adopted a framework that essentially combined the insights of Karl Marx and Tocqueville (a combination, by the way, that explains why James’s interpretation anticipates the work of consensus historians like Louis Hartz). Tocqueville was, in James’s view, ‘the most remarkable social analyst, native or foreign, to examine personally the United States’, and, in American Civilization, he promised to ‘write an essay closer to the spirit and aims of de Tocqueville than any of the writers who have followed him’. It was from Tocqueville that James derived his depiction of the North American environment as having provided the liberal notion of ‘bourgeois individualism’ its best start. The same held true for James’s reasoning when he wrote that the UK’s New World colonies, historically ‘without the political and ideological relations of feudalism and a landed aristocracy’, represented, in effect, ‘the ideal conditions for which Europe struggled so hard’. The point for James, it should be emphasised, was not to celebrate US exceptionalism. As with Tocqueville (and Hartz), he aimed at a sober warning about the republic’s unthinking liberalism and its susceptibility to the support of tyrannical rule.

Indeed, American Civilization sounded an alert that liberal democracy had arrived at a moment of palpable historic crisis. By the mid-20th century, hope in the idea of Americanism as heroic individual freedom was exhausted. Disenchantment with the nationalist liberal creed had been growing over the course of the 19th century, according to James, especially with the rise of corporate capital in the Gilded Age. With the Great Depression, however, its fate was sealed. For the masses of Americans, the ‘struggle for happiness’, once real, had become futile. ‘The worker during the last twenty years no longer has any illusions that by energy and ability and thrift or any of the virtues of Horatio Alger, he can rise to anything,’ observed James. Instead, the average American felt demoralised and objectified, not unlike another ‘piece of production as is a bolt of steel, a pot of paint or a mule which drags a load of corn’. Their dreams and aspirations lay strangled by the undemocratic organisation of economic life, which, under corporate capital, ‘imposed a mechanized way of life at work, mechanized forms of living, a mechanized totality which from morning till night, week after week, day after day, crushed the very individuality which tradition nourishes and the abundance of mass-produced goods encourages.’ What most struck James about the masses of working people in the US was the ‘bitterness, the frustration, the accumulated anger’ that lurked within them. He saw in them the kind of despair and alienation that stalked interwar Europe.

Although these despairing masses had not yet gone the barbarous route of totalitarianism, James found ominous signs in the kind of fictions they chose for entertainment. In the films, books, magazines and comics patronised by the US working classes, he diagnosed a desire for a new kind of fundamentally and violently undemocratic hero. The public were entertaining themselves with stories of protagonists with ‘totalitarian tendencies’. In his view, it was their way of negotiating the tensions between the promise of individual freedom and the reality of ‘the endless frustration of being merely a cog in a great machine’. Here was the analytical climax to American Civilization: a critical examination of ‘what is so lightly called the “entertainment industry”’ as an expression of the deepest feelings of the people. James justified this approach by pointing out that the products of the business had to appeal to the audience, that they ‘must satisfy the mass’ or, at the least, must not offend them. The people were not ‘passive recipients of what the purveyors of popular art give to them,’ James insisted. Granting more agency to consumers than most of his Marxist contemporaries, he noted that the paying mass ‘decides what it will see. It will pay to see that.’ And in the materials that the public were electing to see, listen to and read, he concluded, lay evidence of an attraction to a vicious fictional character.

Hinted at a century earlier in Moby Dick, this totalitarian protagonist had been flourishing on the entertainment scene since the Great Depression, according to James. Whether discussing the comic strip Dick Tracy, the film The Public Enemy (1931) or the bestselling fiction of the now largely forgotten African American writer Frank Yerby, he underlined the avid popular demand for a new type of hero, one who was amoral, primitivistic and endowed with more than a twist of misogyny. Embodied in what James called the ‘gangster-detective’, this character displayed a brutal disdain for the established order. Here was a protagonist who ‘lives in a world of his own according to ethics of his own’, a man who was ready to ‘break every accepted rule of society’. For James, the gangster-detectives epitomised the legendary free individuality of US nationalist myth. They ‘live grandly and boldly. What they want, they go for.’ And although virtually all of them eventually learn that ‘crime does not pay’, they nevertheless give audiences the pleasure of seeing them acting out heroically, dying while trying. In this way, according to James, the fictions churned out by the entertainment industry served ‘to many millions a sense of active living, and in the bloodshed, the violence, the freedom from restraint to allow pent-up feelings free play, they have released the bitterness, hate, fear and sadism which simmer just below the surface.’ The American dream was degenerating into the image of the American gangster.

James worried about the crossover of manufactured Hollywood heroism from entertainment to politics

The popular demand for this new totalitarian hero was not accidental but indexical, James stressed: ‘The gangster did not fall from the sky nor does he represent Chicago and the underworld.’ Rather, expressed in this protagonist was an unmistakably American desire for what was no longer possible in society, for the ‘old heroic qualities in the only way he can display them’. The gangster-detective was ‘the derisive symbol of the contrast between ideals and reality’ in a society where the myth of ‘Americanism’ no longer held; he was ‘the persistent symbol of the national past which now has no meaning – the past in which energy, determination, bravery were certain to get a man somewhere in the line of opportunity.’ For James, this fictional hero betrayed the real-life frustrations of audiences, providing them ‘an esthetic compensation in the contemplation of free individuals who go out into the world and settle their problems by free activity and individualistic methods.’ In the world of popular entertainment, he saw Americans indulging totalitarianism as a resolution to their nationalist crisis of liberalism.

Finally, and maybe most originally, James identified resources for totalitarianism not only in the industry’s projections of fictional protagonists but also in its production of ‘stars’ in reality. Since the Great Depression, he noted, a vital development in popular culture involved the professional packaging of celebrities (Hollywood actors, especially) into ‘synthetic characters’, produced by a ‘vast army of journalists, magazine writers, publicity men, etc’. The rise of these stars concerned James because he believed that through them the masses ‘live vicariously, see in them examples of that free individuality which is the dominant need of the vast mass today.’ Celebrities, he wrote, ‘fill a psychological need of the vast masses of people who live limited lives.’ In this regard, James saw an intrinsic connection between the industrial fabrication of these real-life heroes to be consumed by the admiring masses and the conditioning of the public for totalitarian rule: ‘We have seen how, deprived of individuality, millions of modern citizens live vicariously, through identification with brilliant notably effective, famous or glamorous individuals. The totalitarian state, having crushed all freedom, carries this substitution to its last ultimate.’ The entertainment industry’s heavy investment in the production of stars readied the republic for an antidemocratic regime.

In fact, the ultimate worry in James’s analysis of US popular culture was the potential crossover of manufactured Hollywood heroism from entertainment to politics. The feared translation of the celebrity into a totalitarian leader had not yet happened, but the potential had appeared in the figure of the ‘radio priest’ Charles Coughlin: ‘For a brief period Father Coughlin showed the political possibilities that slumber behind these manifestations of our time. Other countries in the modern world have shown not only the possibilities but the realities.’ Though not even the genius of James could have predicted the celebrity presidency of Donald Trump, it is almost impossible to read American Civilization faithfully in our times and not find a forewarning. (Indeed, this text gives new meaning to mass entertainment fictions like The Sopranos and The Wire and to entertainers like Jay-Z.)

And read it should be. Even if we can no longer avoid the antidemocratic predicament about which James warned, we can still turn to James’s writing for some illumination as to how the US ended up here in this darkening place.