Does a writer, in changing names, change persona, assume a different personality, a disguise, whether consciously or unconsciously? When Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin (or simply Aurore to her friends) married Casimir, she became a ‘Dudevant’ and acutely aware of her identity as his wife. When she adopted the pseudonym ‘George Sand’, it was for her, at least in retrospect, a highly significant moment. She wrote about it in her autobiography, Histoire de ma vie (1854-55), or The Story of My Life, in striking terms that exploit a rich and revealing metaphorical language:

I was baptised [my italics here and later in this quotation] unknown and unaware, between the manuscript of Indiana – which was, at the time, my whole future – and a thousand-franc note – which was at the time my entire fortune. It was a contract, a new marriage between the poor apprentice poet that I was and the humble muse who had consoled me in my troubles … What’s a name in a world that has been revolutionised and remains revolutionary? … The one I’ve been given I have made myself and alone … by my own labour … I don’t feel that anyone should reproach me, … my conscience sees nothing to change about the name that designates – and personifies it.

Do we assume that the references to the ‘revolutionary’ point to new ideas about legitimacy, about rights assumed by birth, that is, as a function of heredity, as opposed to rights bestowed by the state, with popular support? Indiana (1832) was Sand’s first ‘solo’ novel: the author Jules Sandeau, who had collaborated with her earlier, had played no part in it. Previously, their joint works had been published under the name ‘J Sandeau’, and Aurore was advised to retain the ‘Sand’ prefix for commercial reasons.

Two years earlier, the July Revolution, or Trois Glorieuses, had taken place, in which supporters of the (Bourbon) King Charles X and those of Louis Philippe (d’Orléans) clashed. Rival notions of ‘legitimacy’ were at the heart of the matter: the ‘legitimists’ upheld the hereditary rights of the Bourbon branch of the French royal family, while the ‘Orleanists’ favoured the notion of popular sovereignty. And much of Sand’s language here is the language of ‘legitimacy’.

With reference to the above quotation, ‘baptism’ confers legal legitimacy. Marriage is a legal contract guaranteeing, among other things, the legitimacy of children. Sand’s association of her adopted name with her ‘conscience’ suggests that her work will have integrity and honesty, even ‘legitimacy’, despite being written under this assumed name. Had women authors at the time been accepted as equals alongside their male counterparts, it is unlikely that Aurore – or the large number of other contemporary women writers in France, England and elsewhere – would have felt the need to pass themselves off as men by adopting male pseudonyms.

This pseudonymous disguise was far from the first male cover that Aurore had worn. Some of these earlier male disguises are described in Histoire de ma vie. As a very small child, she had been taken to Madrid, where her father was stationed as aide-de-camp of Joachim Murat, military commander and brother-in-law of Napoleon I. Murat was in charge of the French Army during the Dos de Mayo Uprising, a popular revolt that led to the Peninsular War. He was famous for his gregariousness and his extravagant uniform complete with gold details and feathers. Aurore was dressed as a miniature aide-de-camp. Perhaps Murat had initially showed disapproval of an aide-de-camp bringing his family in tow, she speculates. He was, however, quickly charmed by the game:

Every time I was presented to him, I had to put on the uniform. The uniform was a marvel. We kept it at home for a long time after I had grown too big for it. So, I can remember it in minute detail. It was made up of a white cashmere Hussar’s jacket, fully edged with fine gold buttons, a similarly decorated pelisse edged with black fur and thrown over the shoulder, and purple cashmere trousers with gold details and embroidery in the Hungarian style. I also had red Moroccan leather boots with gold spurs, the sabre, the belt …, nothing was missing. Seeing me kitted out exactly like my father, either he mistook me for a boy, or he wanted to give the impression of having been tricked … He presented me as his aide-de-camp to everyone who came to him and admitted us into his inner circle.

Aurore must have learnt a great deal from the experience, whether or not she was very aware at the time: not least, that she was admired as a miniature version of her father. More importantly, she must have been made aware that what is worn, the ‘disguise’, changes the way others behave. But whatever the delights of the theatre, the outfit was uncomfortable. However well she strutted, trailing her sabre and with her pelisse deftly thrown over her shoulder, as she describes, she was unbearably hot and very happy when taken home and relieved of her costume. There, her mother would dress her instead in contemporary Spanish fashion, in a black silk dress complete with velvet-trimmed mantilla.

This was the first of Sand’s many experiments in cross-dressing.

When Aurore left her husband and children, by arrangement, to live in Paris, initially for periods of three months at a time, she soon realised that dressing like a young man would allow her to go to the theatre and stand in the stalls – or at least that was the given rationale. At the time, stalls in the theatre, which were relatively cheap, were open only to men; women occupied the more expensive seats on the balconies or in boxes. This act of disguise she gives a certain legitimacy, in her autobiography, claiming that this was at her mother’s suggestion, and that her mother had done the very same thing herself at a similar age – and that it was her father’s idea:

When I was young and your father was hard-up, he had the idea of dressing me as a boy. My sister did the same thing, and we went out on foot with our husbands, to the theatre, everywhere. It halved our household bill.

But this apparently pragmatic solution itself disguises more complex explanations for Aurore’s cross-dressing. Soon after her arrival in Paris, she had visited Henri de Latouche, friend of Honoré de Balzac, mentor and editor of aspiring young authors. He read the manuscript that she had brought to Paris, deemed it unpublishable, and offered advice:

… you have to live in order to know about life. The novel is life told with art. You have an artist’s nature, but you fail to take account of reality, you live too much in a world of fantasy. Be patient, allow time to pass and experience to accumulate, calm down. These two sad guides [time past and experience] come all too quickly.

How was an unchaperoned young woman novelist to take fuller account of ‘reality’? How was she to ‘allow experience to accumulate’? The obvious answer was to assume the freedoms of a young man and to circulate, alone, unchaperoned, in Paris. Her boots become both the means, and the symbol, of that sense of liberation:

I can’t describe how delighted I was by my boots; I would willingly have slept with them, as my brother when he was very little, when he was given his first pair. With their little metal heels, I was firmly grounded on the pavement. I dashed from one end of Paris to the other. I felt I could have gone round the world. There was nothing to harm my clothes and I went out in all weathers, I came home at all hours, I went to the stalls of all the theatres. No one took any notice of me or questioned my outfit. Apart from the fact that I wore it well, the absence of any style in my clothes or coquettishness in my physiognomy discouraged any suspicion. I was too badly dressed, and my look too simple (my habitual look, preoccupied, unashamedly stupid) to attract or sustain anyone’s interest … Not to be noticed as a man, one has first to be used to not being noticed as a woman.

Pragmatism clearly played a major role in Sand’s decision to dress this way. It gave her all the freedoms otherwise denied her sex. But she suggests more: that not to be noticed requires an asexuality, or at least a distinct lack of sex appeal – whether male or female. The physical freedom that her appearance allowed her symbolised a more fundamental freedom. As in so many areas of her life, voyeurism played a part. Dressed as a man and having perfected a facial expression that allowed her to pass quite unremarked, she could circulate and see without being seen. This invisibility she experienced as miraculous and inspiring:

I was no longer a woman, nor was I a man. I was jostled on the pavements like a thing [my emphasis], an impediment to busy passers-by. It didn’t matter to me; I had no business. No one knew me, no one looked at me, nobody stopped me: I was an atom lost in that immense crowd … In Paris [unlike La Châtre in central France, where she’d come from] no one thought anything of me, no one saw me … I could invent an entire novel… without meeting a single person who would say: ‘What in heaven’s name are you thinking about?’

In a letter to her mother, written in the summer of 1831, she explained that it was not primarily the society and entertainment of Paris that she needed, but simply ‘to be alone in the street’. Her consuming passion was to see, to listen, to accumulate ideas, to witness emotion that would nourish her writing. It was a way, despite being a young woman, fully to take account of Latouche’s advice ‘to live in order to know about life’.

Women who wanted to dress in men’s clothing had to be granted a permit from the local police station

‘Nobody stopped me.’ It would be easy not to take account of the risks that Sand was running in passing herself off as a young man. The adoption of male dress and the lifestyle it automatically facilitated was, quite literally, illegitimate at the time, that is, ‘contrary to the law’, as Nicole G Albert explores in her book Lesbian Decadence (2016). Cross-dressing was prohibited according to a decree of November 1800 during the Consulate (1799-1804, immediately before the beginning of the Napoleonic Empire). This required men and women to dress in clothing appropriate to their sex, and forbade women to wear trousers. In 1810, the law recognised the practice as an ‘infraction’: an offence to public decency and morals, and subject to a fine. Women who wanted to dress in men’s clothing had to apply for, and be granted, a permit from the local police station. The licence, initially intended for a specific activity, often functioned as a permanent pass. According to the contemporary (and acerbic) essayist Laurent Tailhade, the archaeologist’s wife Madame Dieulafoy – who had applied for a permit to dress in trousers for ‘scientific tourism’, that is, assisting her husband on archaeological digs – was still wearing a tuxedo 20 years after the licence had been granted.

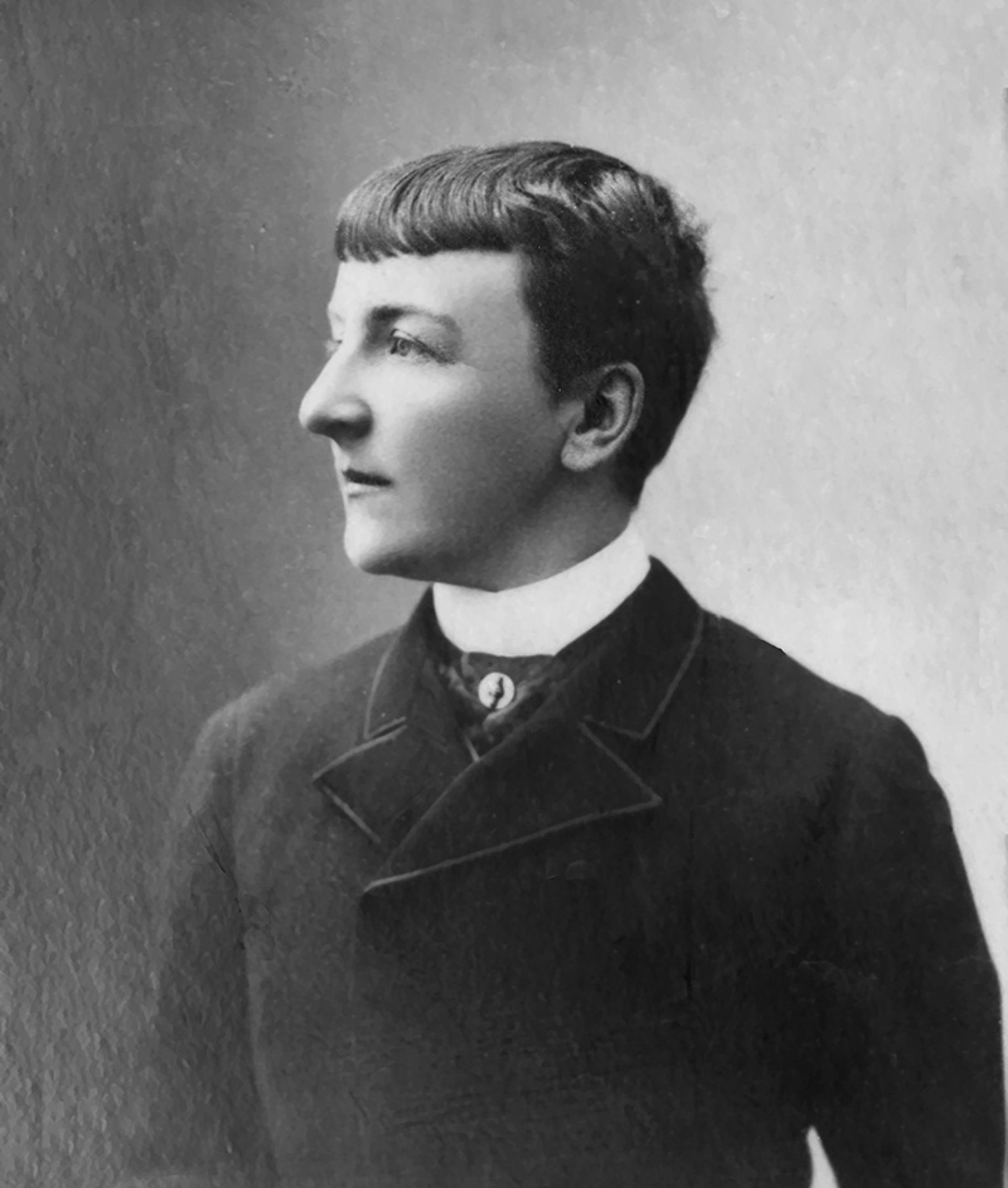

Jane Dieulafoy, archaeologist, explorer and novelist in 1895. Photo courtesy Wikimedia

The generally accepted reason for the ban on women in trousers was a fear that it would facilitate women taking men’s jobs. But it is hard not to believe that there were psychosexual fears – and excitements – too. One of the few direct – if nevertheless cryptic – expressions of this was Adrienne Saint-Agen’s. A novelist herself, she had no doubt observed some of the interactions to which cross-dressing gave rise: ‘A cross-dressed actress has such a charming and intense attraction that it quickly becomes unhealthy.’ In what ways this might be ‘unhealthy’ she does not explain.

A fuller account of same-sex attraction, or of the allegedly ‘unhealthy’ consequences of cross-dressing is provided by the American playwright Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972), who spent most of her working life in Paris. She wrote:

The affectations of the French 18th century were naughty childish pursuits, the subjects of paintings on fashionably suggestive fans, of pastoral poetry, queens’ flirtations, trifling liaisons, visual piquancies, minor dalliances, bedcovers always turned down, nonstop sensual pleasures, more fatigued than perverted. The advent of Romanticism was needed to inject a semblance of sinful ‘vice’ into these feminine couples and to dissipate the insipidness and the ‘charming disarray’ of these ‘turtledoves’.

The philosopher Michel Foucault provides a further insight into the ways in which ‘sex’ was seen, and changed, in modern Europe, in his introduction to the book Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a 19th-century French Hermaphrodite (1980), which the scholar Pratima Prasad explores in her paper ‘Deceiving Disclosures’ (1999). In the Middle Ages, canon and civil law did not conceive of the idea of a ‘true’ or ‘single’ sex. Anyone of indeterminate sex was designated as hermaphrodite, assigned a ‘sex’ during baptism and could, at a later stage, choose with which sex they wished to identify. Later, physiological and legal conceptions of the individual made gender ambiguity less and less acceptable, and the individual was gradually given very little freedom in choosing his or her sex. In the latter half of the 19th century, studies of sexual identity and their classification also included inventions of ‘sexual perversion’ and ‘gender deviance’. Foucault was fascinated by Barbin, a ‘19th-century hermaphrodite’. After a medical examination in middle age, s/he was deemed to have the characteristics of a male body, and was compelled to assume a definitive male identity. Hermaphrodism, or what Prasad calls ‘gender equivocation’, was no longer an option.

The psychosexual upset that cross-dressing – and sexual indeterminacy – could apparently cause became a subject of comment around the same time. The director of the daily newspaper Le Courrier français sponsored a Women’s Ball during the 1892 Carnival in which men had to come dressed as women; this idea was deemed ‘abnormal’ by Jules Bois, who decried ‘the melding of two sexes into one and the merging of all human attractions into a single organism.’ The day after the ball, one commentator wrote of ‘the attractive and disturbing power of the transvestite’, arguing:

We must take care not to confuse the transvestite and fancy dress. Perversity and flirtatiousness originate in the transvestite and permeate the disguise; our imagination and others’ desires are stimulated by the thought of one sex grafted onto another in order to hide it while letting it show through; thus, it awakes the ambiguity in our hearts and our senses … Of all the tricks that a woman might use to inflame and stir our imagination, cross-dressing is certainly the most corrupting. Cross-dressing perverts us and makes us wonder.

The myriad complexities of cross-dressing that were the subject of so much lively discussion and extreme polemic during Sand’s lifetime are arguably less relevant to her life than to her fiction. Cross-dressing heroines are everywhere to be found: the eponymous Lélia (in Sand’s novel Lélia of 1833, as opposed to the ‘cleaned up’ version of 1839) disguises herself as a poet for a masquerade ball; the heroine of Consuelo (1842-43) assumes a peasant boy’s dress on one of her journeys; and in its sequel, La Comtesse de Rudolstadt (1843-44), Wanda wears the same outfit as her male colleagues in the secret society to which they belong. In the play Gabriel (1839), transvestitism becomes the focus of the dialogue, which explores the psychological, sociopolitical and economic consequences of living as a transvestite.

The often straightforward pragmatism of Sand’s cross-dressing in life becomes a perplexing, mysterious and paradoxical subject in her fiction. Insofar as there is any ‘solution’ for Gabriel, who is brought up as a boy in order to inherit but later told that she is a young woman (and fails to inherit), it is in suicide. Furthermore, Gabriel has claimed: ‘As for me, I don’t feel that my soul has a sex.’

George Sand photographed by Nadar in 1864. Courtesy Wikimedia

It is the very uncertainty, androgyny or indeterminacy of the cross-dressed character that is so thought-provoking and intriguing. As a child, in Madrid, Aurore had wondered at the image of herself in a large cheval mirror, appropriately called a psyché in French, and had been fascinated by the echo of her own voice, which she assumed to be the voice of someone else replying. This sense of a double has, eventually, to be reconciled. What mattered to George Sand – and no doubt what matters to everyone – is the right to be true to a single self. In her autobiography, she wrote:

To be an artist! Yes, that’s what I wanted, not only to escape the prison house of materialism where property, large or small, locks us into a loathsome vicious circle of preoccupations; to distance myself from the control of public opinion, its narrowness, its foolishness, its egoism, its slackness, its parochialism; to live outside the world’s prejudices, its falsity, its backwardness, its arrogance, cruelty, its irreligion, its stupidity; but also, and above all, to reconcile myself with myself.