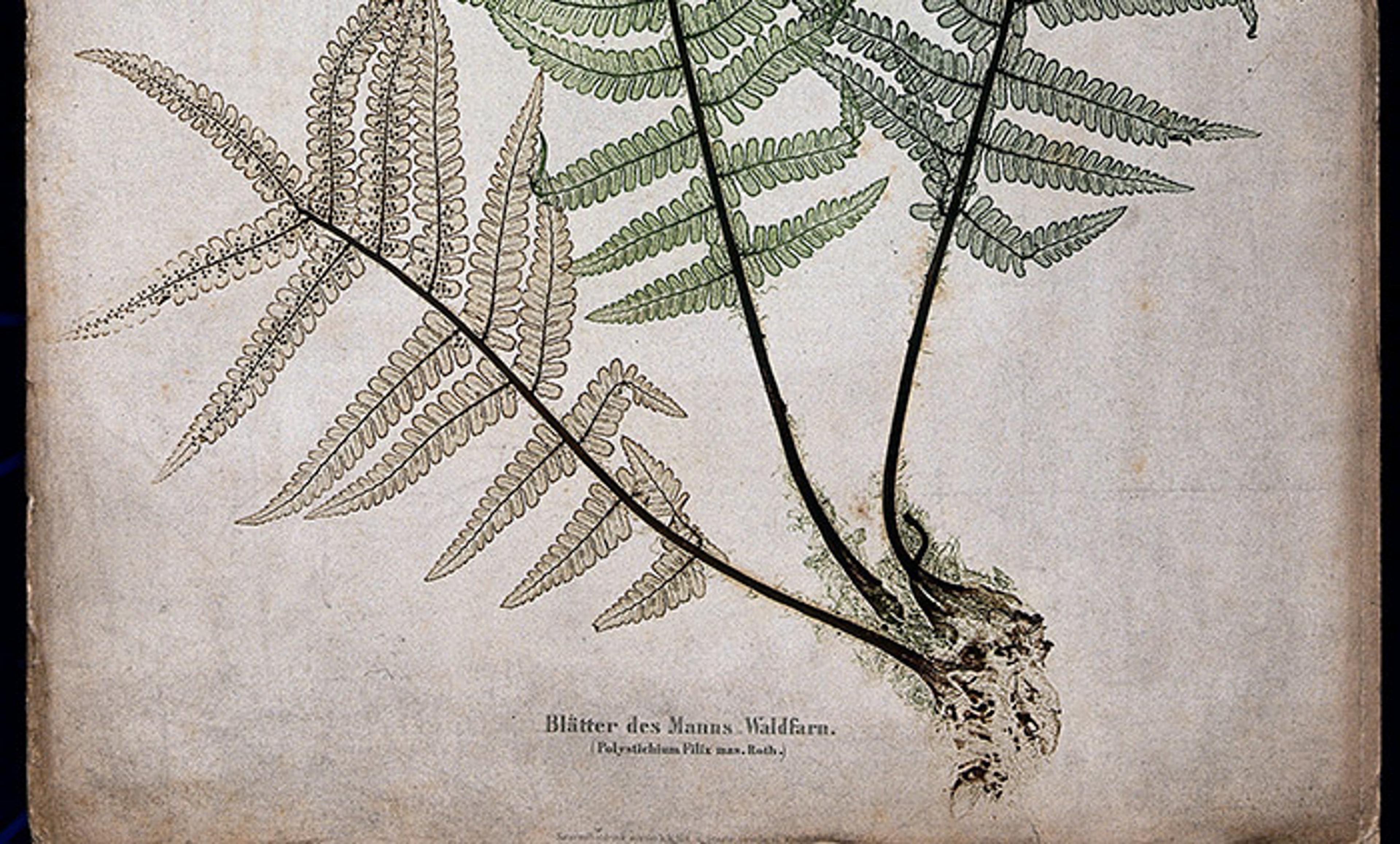

The male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas): fronds and part of rhizome. Colour nature print by A. Auer, c. 1853. Courtesy Wellcome Images

Scholars add to human knowledge and help us to see and understand the world in new ways. To do so, they often invent and use concepts that are not part of ordinary language. This specialised scholarly language is known as jargon, and it can elicit scorn, especially outside the academy. But to criticise jargon as such is tantamount to saying that scholars should not go beyond common sense, which is a betrayal of their vocation. Though scholars might abuse jargon, they often need it to push the borders of thought.

Take Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus (1980), a source of much jargon in the contemporary humanities and social sciences.

Deleuze began his career writing monographs on philosophers such as David Hume, Friedrich Nietzsche and Baruch Spinoza. Guattari was a practising psychoanalyst when he began to work with Deleuze on their first book, Anti-Oedipus (1972). Eight years later, they published its sequel, A Thousand Plateaus. In the past few decades, academics across the world and in various disciplines have adopted its language of rhizomes, plateaus, abstract machines, concrete assemblages, and fields of immanence.

Why did they invent such strange philosophical concepts as rhizomes? One reason is to help us appreciate the singularity of each thing as well as each thing’s myriad connections to other things. This vision of an interconnected world of singularities, in turn, can change how we act in the world.

According to Deleuze and Guattari, Western thinking and practice has tended to be ‘arborescent’, or tree-like. One quality of trees is that they are born from seeds. Seeds from one tree can impart the same genetic makeup to many other trees. Trees are Platonic insofar as there is one idea and multiple instantiations. ‘Arborescent’ illuminates the Platonic presuppositions that course throughout Western politics, philosophy, science, art and so forth. Platonism reassures us that there is a cosmic order where there is a perfect instantiation of each thing. We often think that there is just one idea of justice or beauty or good health. Common sense of this sort is arborescent.

According to Nietzsche, the task of modern philosophy is to overturn Platonism, to stop looking for eternal blueprints of how things should be, and instead value this world of difference and becoming. Taking up this assignment, Deleuze and Guattari propose that we think in terms of ‘rhizomes’. A rhizome is a plant such as a potato, couch grass or bamboo. Rhizomes do not have seeds or trunks; rather, they shoot out stems and reproduce when a part breaks off and grows again, each one slightly different from its predecessor. A Thousand Plateaus helps us see the distinctiveness and connectivity of multiple things that compose reality. ‘A rhizome,’ they wrote, ‘ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organisations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.’ The concept of the rhizome helps us to view our lives as assemblages of words, institutions, songs, medicines, social movements, and countless other things that are related but also distinct.

Many scholars, and also architects and artists, have found Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome invaluable at describing how things can often be more complicated and intertwined than common sense recognises.

The political theorist Cristina Beltrán, for instance, uses the concept of the rhizome in her book on Latino politics, The Trouble with Unity (2010). Beltrán takes issue with the reigning conception of Latinidad, the notion that all people from Latin America share the same group identity and cultural consciousness. Beltrán notes that commentators often assume that Latinos are a ‘sleeping giant’ that will wake up to a collective identity and transform US politics. This is arborescent thinking. Unfortunately, arborescent thinking can contribute to Puerto Rican and Chicano movement leaders suppressing feminist demands for the sake of unity. Arborescent politics can be cruel.

Latinidad life and politics, Beltrán shows readers, are actually without a centre, or trunk. They are rhizomatic. Seeing Latinidad society in the US this way is not only closer to reality, it helps us find ‘value in its capacity to be decentred, opportunistic, and expansive’. Rhizomatic Latinidad helps us perceive elements that depart from the norms of Latino identity. Thus, Beltrán spotlights anomalous elements such as Puerto Rican libertarian college students in New Jersey, Chicano environmentalists attending a Morrissey concert in Los Angeles, and ‘queer’ Cuban radicals working on Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign. The concept of the rhizome provides a more nuanced, and generous, view of identity politics.

Nearly all political phenomena have arborescent or rhizomatic elements. People often tend to think of political parties as having an ideological centre, but a rhizomatic perspective prompts us to see the fractures and divisions within political parties. For example, there are Republican senators in the US who voted against the confirmation of the secretary of education Betsy DeVos, despite her nomination by a Republican president. There are also Democratic politicians in the US who hold that the country needs more charter schools, a position more popular in the Republican party. This analysis can be pushed further as we consider how rhizomatic offshoots from both political parties coalesce into new assemblages: the anti-Common Core movement. All around the world, for example at a recent Deleuze Studies Conference in India, scholars talk about rhizomes to try to gain a better understanding of politics, philosophy, cinema, design, and urban planning.

True, people can use jargon to intimidate others, to make simple ideas appear complex, or lead themselves into intellectual dead ends. In 1995, Alan D Sokal, a professor of physics at New York University, published a hoax article in an academic journal that includes quotes from Deleuze and Guattari. The Sokal controversy reminds us that scholars can use big words to puff up nonsensical ideas. People can easily use Deleuze and Guattari’s terminology – including the notorious concept of the ‘body without organs’ – in ways that neither convince scholars nor help others understand their ideas.

The wrong lesson of the Sokal controversy, however, is that people in the humanities or social sciences must always use familiar language. In Deleuze and Guattari’s work, technical terms and neologisms almost always have precise etymologies and convey clear images. At its best, their philosophical language helps us to perceive the elusive factors of reality that affect what we can more easily see and measure.

As a general rule, scholars should speak as clearly and as simply as they can, without compromising the integrity of their ideas and enquiries. Few people complain when scientists or mathematicians use a technical vocabulary, and that courtesy should be extended to scholars in the humanities and the social sciences. Many common-sense terms today – such as paradigm shifts and electoral realignments – started off as jargon, and we could anticipate and welcome other scholarly terms making that transition. Rhizomes.