In early 2017, Scientific American published a symposium on the threat that ‘big nudging’ poses to democracy. Big Data is the phenomena whereby governments and corporations collect and analyse information provided by measuring sensors and internet searches. Nudging is the view that governments should build choice architectures that make it easier for people to pick, say, the more fuel-efficient car or the more sensible retirement plan. Big nudging is the combination of the two that enables public or private engineers to subtly influence the choices that people make, say, by autofilling internet searches in desirable ways. Big nudging is a ‘digital sceptre that allows one to govern the masses efficiently, without having to involve citizens in democratic processes’. The symposium’s authors take for granted that democracy – the political regime in which the people collectively determine its common way of life – is better than epistocracy, or rule by experts.

Remarkably, many social scientists today do not share the belief that democracy is better than epistocracy. On the contrary. In recent years, numerous political theorists and philosophers have argued that experts ought to be in charge of public policy and should manipulate, or contain, the policy preferences of the ignorant masses. This view has its roots Plato’s Republic, where philosophers who see the sun of truth should govern the masses who dwell in a cave of ignorance, and in Walter Lippmann’s Public Opinion (1922), where expert social scientists rule behind the scenes and control the population with propaganda. While there are differences between the views of Christopher H Achen and Larry Bartels in Democracy for Realists (2016), Jason Brennan in Against Democracy (2017), Alexander Guerrero here in Aeon, and Tom Nichols in The Death of Expertise (2017), these social scientists share in common an elitist antipathy towards participatory democratic politics.

In Democracy for Realists, for instance, the authors criticise what they call the ‘folk theory’ of democracy. This maintains that elected representatives should translate their constituents’ preferences into public policy. The problem, according to these political scientists, is that most voters lack the time, energy or ability to immerse themselves in the technicalities of public policy. Instead, people tend to vote based on group identification, or an impulse to align with one political faction rather than another.

In a memorable chapter of their book, Achen and Bartels show that politicians often suffer electoral defeat for events beyond their control. In the summer of 1916, for example, New Jersey’s beachgoers experienced a series of shark attacks. In that November’s election, the beach towns gave President Woodrow Wilson fewer votes than New Jersey’s non-beach towns. The voters, it seems, were punishing Wilson for the shark attacks. According to Achen and Bartels, voters’ ability ‘to make sensible judgments regarding credit and blame is highly circumscribed’. This is a polite way of saying that most voters are not smart enough to realise that presidents are not responsible for shark attacks.

Achen and Bartels ostensibly defend a conception of democracy. But the force of their argument, and spirit of their book, heaps ridicule on the ‘Romantic’ or ‘quixotic’ notion that the people should rule. They compare ‘the ideal of popular sovereignty’ – a cornerstone of modern democratic political theory – to the medieval notion of a ‘divine right of kings’. A more realistic view is that ‘policymaking is a job for specialists’.

Many political actors around the world, similarly, think that epistocrats should rule and try to gain the emotional support of the population. Consider the slogan of the Democratic Party in the 2016 US election: ‘I’m with her.’ The Democrats were telling their own version of Plato’s salutary myth, or simple story meant to induce people to identify with a political cause.

Democracy, instead, requires treating people as citizens – that is, as adults capable of thoughtful decisions and moral actions, rather than as children who need to be manipulated. One way to treat people as citizens is to entrust them with meaningful opportunities to participate in the political process, rather than just as beings who might show up to vote for leaders every few years.

Democrats acknowledge that some people know more than others. However, democrats believe that people, entrusted with meaningful decision-making power, can handle power responsibly. Furthermore, people feel satisfaction when they have a hand in charting a common future. Democrats from Thomas Jefferson and Alexis de Tocqueville to the political theorist Carole Pateman at the University of California in Los Angeles advocate dispersing power as widely as possible among the people. The democratic faith is that participating in politics educates and ennobles people. For democrats, the pressing task today is to protect and expand possibilities for political action, not to limit them or shut them down in the name of expert rule.

Every day, people demonstrate that they are capable of learning. People master new languages, earn degrees, move to new cities, train for jobs, and navigate the complexities of modern life. It is true that people tend to be ignorant of things that do not touch their lives. Think of how well you know the geography of where you live and work; now, think about how much you know about the geography of a place on the other side of the globe that you’ve never visited. People study things that they care about and where knowledge helps them to accomplish things.

People also show every day that they can take an interest in other people’s lives. Last summer, I served on a grand jury in Westchester County in New York State. The county randomly called upon 23 eligible adults to hear evidence to determine whether the district attorney could move forward with criminal indictments. Everyone in the jury took their responsibilities seriously, following the district attorney’s directions, asking questions of witnesses, participating in the deliberations, and voting. Before grand jury service, many of us had little knowledge of criminal law or standards of legal evidence; afterwards, most of us did. We learned by doing.

The ‘best and the brightest’ led the US into the Iraq War: the track record of epistocracy is, at best, mixed

Pateman gives other examples of ways to involve more people in the policymaking process, including citizens’ assemblies to review the electoral system in Canadian provinces, or participatory budgeting in the city of Porto Alegre in Brazil. In these instances, citizens assembled in mini-publics and, given time for discussion and research, became knowledgeable about public matters. Just as importantly, ‘the empirical evidence from mini-publics shows that citizens both welcome and enjoy the opportunity to take part and to deliberate, and that they take their duties seriously’.

It is misleading to say that most people are too ignorant or apathetic to participate in political affairs. In the right circumstances, many people perform civic functions well. Citizens must consult with experts and are liable to cognitive biases, but this holds true for whoever holds a leadership position in the modern world. Realists criticise most people’s understanding of political affairs, but the democratic response is that people who have no real power lack a reason to study public policy.

In The Death of Expertise, Nichols contends that it is ‘ignorant narcissism for laypeople to believe that they can maintain a large and advanced nation without listening to the voices of those more educated and experienced than themselves’. Of course, the ‘best and the brightest’ led the US into the Iraq War, the subprime mortgage crisis, and a raft of bad education policies; the track record of epistocracy in recent years is, at best, mixed. Furthermore, the elitist stance clashes with the fact that many people demand a say in how we lead our personal and collective lives. Many people today value autonomy, or self-governance, and suffer when it is denied.

One reason why is because of a certain progression in the history of ideas. In The Invention of Autonomy (1997), Jerome B Schneewind shows how the idea of autonomy developed from an intimation in Paul’s Letter to the Romans, to Jean Jacques Rousseau’s conception of freedom as following a law that one gives oneself as a member of the general will, to Immanuel Kant’s practical philosophy that makes freedom its keystone. Other historians have continued this work up to the present, showing how the ideal of autonomy informs modern thinking about economics, race, gender and so forth. Many people share the sentiment of the international disability movement: ‘Nothing about us without us.’

Technological developments have also accustomed people to having some control over their individual and collective lives. Cars, for instance, make it possible for individuals to choose where they want to go; cars cultivate the sense of individual autonomy. At the same time, there is no natural order of cars, and human beings can decide together such questions as whether to create high occupancy vehicle lanes on highways or make it illegal to text on one’s phone while driving. In the medieval world, people might have felt like they were locked into a certain place in their society, but in the modern world they demand a say in the ordering of things. That is why liberalism – a political doctrine that extols individual freedom – and democracy – a political doctrine that valorises collective freedom – are so often intertwined in modern political thought.

Modern people hate to be told: ‘Do it because I say so.’ Alienation from the political process often leads people to identify with strong leaders who claim to represent the silent majority. Across the world, we see political battles between technocrats and populists, experts who claim authority because of their knowledge versus leaders who fight against elites on behalf of the ‘real people’. A third option is democracy, or the notion that flesh-and-blood people can and ought to exercise meaningful power in the governing of common affairs.

Some scholars take a kind of Machiavellian glee in debunking democratic idealism; others extol the ‘wisdom of the crowd’. But the wisdom-of-the-crowd advocates often do not actually call for allotting more political power to most citizens, as in Guerrero’s proposal for lottocracy.

Democracy means people exerting power, not choosing from a menu made by elites and their agents

Guerrero, a philosopher at the University of Pennsylvania, thinks that direct democracy cannot work because most people lack the time and ability to understand the complexities of modern public policy. Democrats have responded to this situation by creating a system of representative democracy where people vote for politicians who act as our agents in the halls of power. The problem is that most people cannot pay sufficient attention to hold their representatives accountable. Citizens are ‘ignorant about what our representatives are doing, ignorant about the details of complex political issues, and ignorant about whether what our representative is doing is good for us or for the world’. To make matters worse, powerful economic interests have the knowledge and resources to capture representatives and make them serve the rich.

The time for electoral representative democracy has passed, argues Guerrero. Rather than waste people’s votes in elections, political systems should create a lottocracy that randomly selects adults who can perform modified versions of the jobs that elected politicians presently do. Right now, US congresspersons are predominantly white, male, millionaires; a lottocracy could instantly raise the number of women, minorities and lower-income people in the legislature, and take advantage of each group’s epistemic contributions to policy debates.

Guerrero envisions single-issue legislatures whose members are chosen by lottery and serve three-year staggered terms. At the beginning of the legislative session, experts set the agenda and bring the legislators up to speed on the topic, then the legislators draft, revise and vote on legislation. Guerrero dismisses the possibility that experts ‘would convince us to buy the same corporate-sponsored policy we’re currently getting’.

On the contrary, the wealthy and powerful could easily manipulate a lottocracy. Think tanks and lobbyists, funded by economic elites, would welcome the opportunity to educate lottery-chosen legislators. Those who set the agenda make the most important decisions. This is the democratic critique of plans that tightly regulate the ways that people may participate in politics. Democracy means people exerting power, not choosing from a menu made by elites and their agents.

The remedy for our democracy deficit is to devolve as much power as possible to the local level. Many problems can be addressed only on the state, federal and international level, but the idea is that participating in local politics teaches citizens how to speak in public, negotiate with others, research policy issues, and learn about their community and the larger circles in which it is embedded. Like any other skill, the way to become a better citizen is to practise citizenship.

Jefferson articulated the democratic faith in a remarkable series of letters in the early 19th century. He first denounces the idea, shared by fellow American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton and the French philosophes, that elites should govern from the capital. Concentrating power in this way enervates citizens, and opens the door to aristocracy or autocracy. Jefferson envisions a system of ward republics that empower people to handle local affairs, including care of the poor, roads, police, elections, courts, schools and militia. Jefferson sees a role for counties, states and the federal government, but he wants substantial political power to be dispersed to every corner of the country. When people participate ‘in the government of affairs, not merely at an election one day in the year, but every day’, Jefferson explains, they will protect their rights and fight the accession of a Caesar or a Bonaparte.

A few decades later, the French political scientist Tocqueville argued in Democracy in America (1835-40) that Americans have shown what democracy in the modern world might look like. In France, when people want something done, they petition the centralised government. In the US, by contrast, people form democratic associations to accomplish their shared goals:

Americans of all ages, all conditions, and all dispositions constantly form associations … The Americans make associations to give entertainments, to found seminaries, to build inns, to construct churches, to diffuse books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they found hospitals, prisons, and schools.

The brilliance of US democracy, for Tocqueville, is that it resides in civil society as well as formal governmental structures.

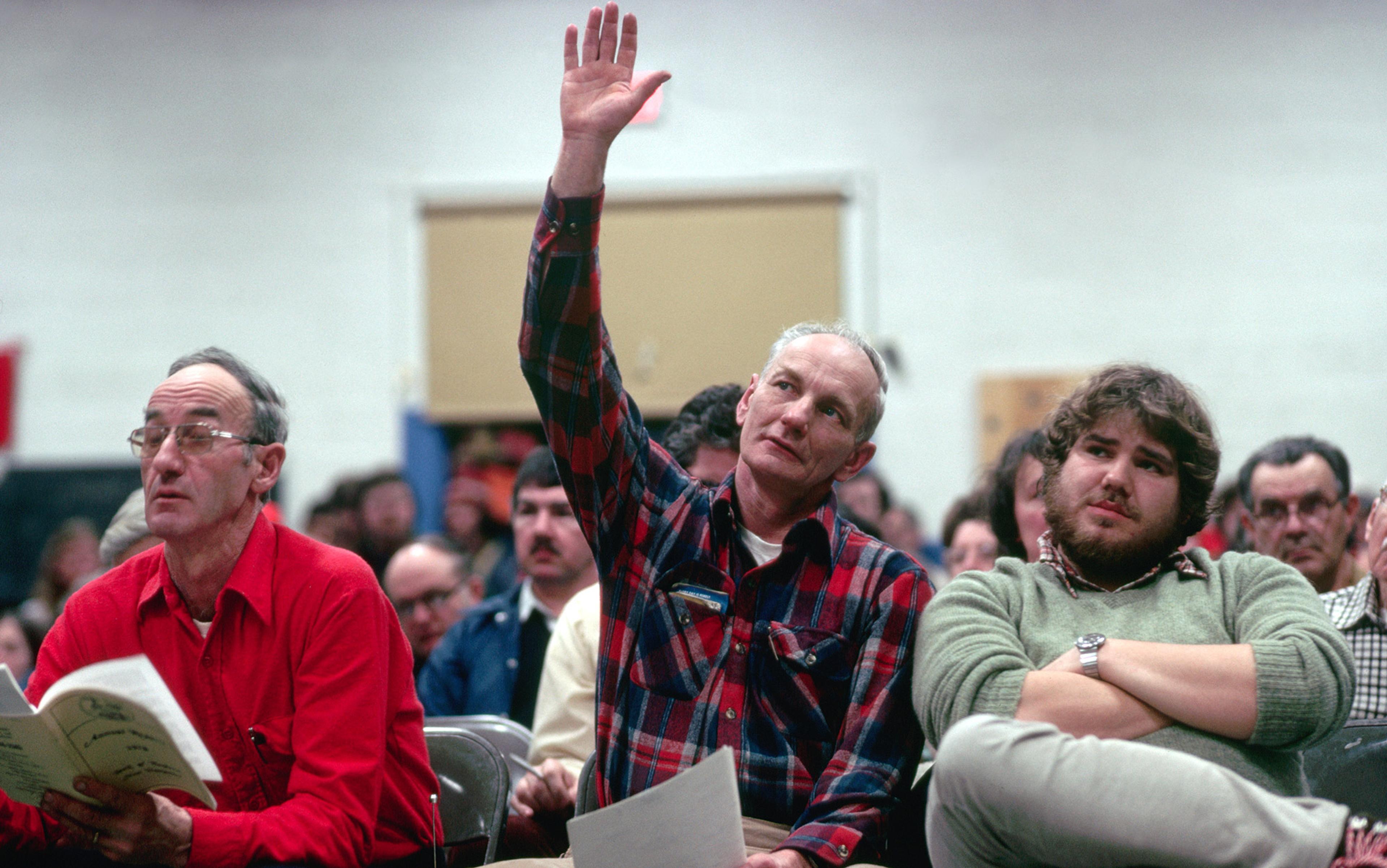

A few years ago, I saw an example of democracy in action when my local school district had a heated debate about the salary of the superintendent. A group of people in the district sent out an email protesting the school board’s approval of a raise for the superintendent who was already one of the most highly paid officials in the state. At the next school board meeting, the district meeting space was filled to capacity and people were sitting on the floor, in the doorways and outside the room. When it was time to discuss the issue, one person stood up and said why she thought that the superintendent was overcompensated, and that resources could be better spent elsewhere. Then, a school board member explained that if the district was going to remain successful, it needed to compensate its leader on a par with other successful executives. The debate was about one person’s salary, but it was also a conversation about what kind of education we envisioned for our children. Many people shared their thoughts and learned what others had to say.

In an epistocracy, a few make all the crucial decisions; everyone else might as well stay at home and watch TV

The discussion about the superintendent’s salary grew heated. People raised their voices, insulted others, and threatened litigation. Tocqueville counsels his readers to see the value of democratic participation that spills outside of the bounds of calm discourse: ‘Such evils are doubtless great, but they are transient; whereas the benefits which attend them remain.’ Because our voices mattered, many parents attended the meeting, voiced their concerns, and heard from others. In a large, centralised school system, each parent has a negligible share of power; but in a small school district, each parent is able to experience the exhilarating feeling of speaking on one’s feet in public about a matter of common concern. Neighbours meet one another, and reaffirm their commitment to making their collective life better.

In an epistocracy, a few people make all the crucial decisions, and everyone else might as well stay at home and watch television. In a participatory democracy, people exercise their civic muscles and become more thoughtful, involved in community affairs, and passionate about making the world a better place. In Against Democracy, Brennan argues that democracy is the site of ‘hobbits’, ‘hooligans’ and ‘vulcans’: this scheme misrepresents the citizens I have met at the grand jury, the school-board meeting, or political demonstrations acting together to solve a common problem.

In modern democracies, expert rule has returned in the form of ‘big nudging’. Maybe not all epistocrats favour this particular technology, but they open the door to it with their critique of the intellectual capabilities of the masses and their advocacy of elite rule.

Scientific American notes that big nudging can lead to a new form of dictatorship based on ‘technocratic behavioural and social control’. Most of the recommendations to combat this threat, however, rely on modifying computer use, including enabling user-controlled information filters, improving interoperability of computer systems, and promoting digital literacy. These measures all miss the essential point: democracy requires empowering people to participate in the political process. There is no algorithm that can replace entrusting people to do the hard work of running community affairs.

The way to learn how to walk is to walk; the way to become a citizen is to exert some kind of power in the government or civil society. There is no technological quick fix to make our society more democratic. To learn what Tocqueville called ‘the art of being free’, people must have a hand in the governance of common affairs.