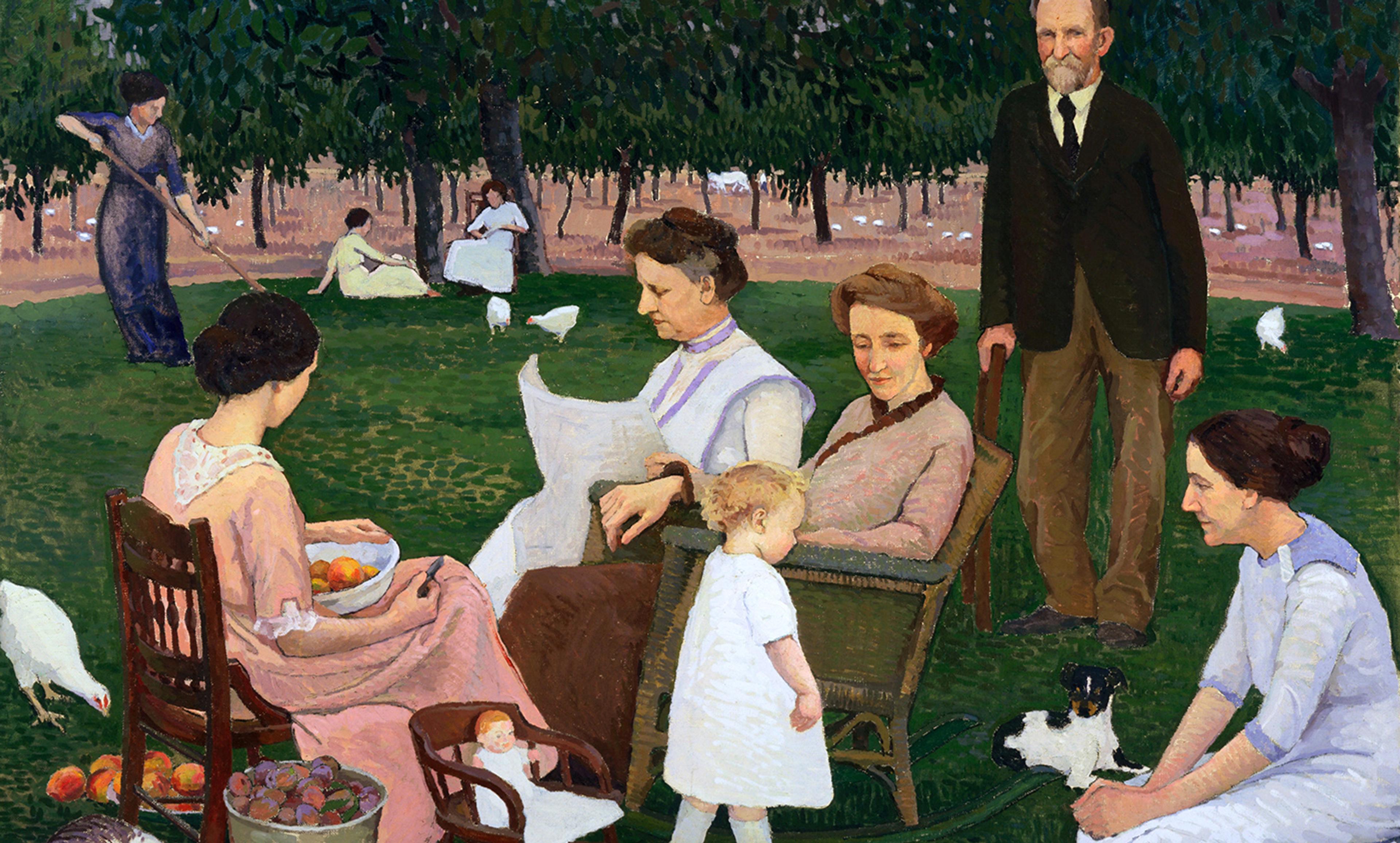

The Orchardist and his Family by Henry Varnum Poor/Freeparking/flickr

The pressures and pace of modern life has made parents and children stressed and miserable. With the rise of dual-earning families, mothers, and increasingly, fathers are struggling with work-life issues, forcing many to lean in or opt out. But is it truly modern life that’s at fault or is it our expectation that two people – whether hetero or same-sex – can do it alone and do it well? Is the nuclear family all it’s cracked up to be?

Despite the belief that monogamous male-female bonding is how mothers and children were supported and thrived, the anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy and others believe it was actually female cooperative breeding, or alloparenting – ‘sharing and caring derived from the pooled energy’ of a network of ‘grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, distantly related kin, and non-kin’ – that shaped our evolution.

Shared parenting is likely in our genes. It works. So why do we cling to the idea that the nuclear family is the best way to raise children?

The nuclear family can be extraordinarily dangerous for children. Some – often children of educated and privileged families – are buckling under pressure to succeed and are committing suicide at alarming rates. Those in the United States who experience parental divorce are overwhelmingly being raised in poverty, which has lifelong ramifications on their health, wealth and education. At the extreme, some 500 children a year are murdered by their parents in the US, and millions more are abused and neglected, with inadequate systems to help them until damage is done.

But even in so-called ‘normal’ families, children can’t escape some sort of dysfunction, whether they’re being raised by a parent who is depressed, adulterous, emotionally cold, smothering, absent, angry, passive-aggressive, narcissistic or addicted. The moral philosophers Samantha Brennan and Bill Cameron suggest that love-based marriage, with the ‘instability, tension, and even violence that too often forms a central part of romantic conflict,’ doesn’t always offer children the stability and security they need.

Parents, too, struggle. It is a lonely, isolating and exhausting business, especially for mothers, who still typically do the bulk of childcare. They pay a huge price for it. Not only do many forsake career opportunities and income, but they also are subject to societal idealisation of motherhood and then shamed and blamed for any perceived failings, most often by their own children.

With all that, can we raise children better? Yes. Rather than leave childrearing solely in the hands of one or two people, it would help everyone if we approached it more along the lines of the old African proverb: ‘It takes a village to raise a child.’ We should take alloparenting to the next level: quality and trained caregiving that is shared, continuous and, most important, mandatory.

For the philosopher Anca Gheaus, communal childrearing makes a lot of sense. In a series of papers, Gheaus explores what childrearing ideally would look like based on children’s rights and emotional needs. While acknowledging that some parental power and decision-making is essential until children can care for themselves, parents often use their power arbitrarily and in their own best interest – not necessarily their child’s. Being a parent shouldn’t automatically give someone a ‘monopoly of care’ over a child, she says, especially since anyone can become a parent without having any training or undergoing any testing to see if he or she’s up for the job.

Which is why Gheaus suggests that some non-parental care should be mandatory. If childrearing became more of a communal obligation, all children, whether subject to disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds or just bad parenting, would benefit. More people would be invested in their lives, and the children would be exposed to a variety of opinions and lifestyles that would enhance their budding autonomy. Having numerous caregivers would expose bad parenting earlier, too, and help to mitigate it. And as they grew into adulthood, children would be more likely to be compassionate – or at least open-minded – toward people whose beliefs and values differed from their parents’.

But how to make that happen?

The collective childrearing on Israel’s kibbutzim has been lauded for giving children high-quality care in a supportive environment, despite problems with its approach to communal sleeping in its early years. While many parents might not opt to live in a communal setting, there are other ways to provide children with a network of people, ideally not related, who care for them.

It could take the form of formalised, but non-religious godparenting, in which children are assigned caregivers who live outside the family home and are willing and able to help care for them several hours a week while they are young, and then become trusted confidantes as they age. There are many men and women who either don’t have children or whose children are grown – or perhaps disenfranchised – but still want to make a difference in a child’s life. Allowing more people to be involved with the lives of children would create a real, communal investment in the future.

It’s easy to see how parents would benefit. Having a trusted, loving network of caregivers would give moms and dads a much-needed break to spend time with each other or alone. They would feel less overwhelmed, especially if they have children with learning challenges or physical disabilities, or have erratic work schedules. It would also help them better manage the ambivalent feelings that parenting elicits, which is ‘inevitably accompanied by anger, frustration, and occasionally even hatred,’ Gheaus writes.

In some ways, we are already doing a form of alloparenting. Many children are raised with multiple parents, whether through same-sex coupling, divorce, open adoption, polyamory or reproductive technology. The sociologist Karen Hansen notes that dual-employed parents rely on friends, paid caregivers and relatives to help. Teachers, coaches, tutors and mentors often fill in the gaps. But many come and go.

And that’s the problem. Children can be cut off from loving caregivers, often because of parental needs or whims. Sometimes they lose access to relatives after a divorce, or to beloved neighbours because of moves or rifts; long-term nannies or babysitters are fired with no regard to a child’s desire to continue the relationship. Parents have no moral right to do that.

Besides helping children and parents, alloparents would benefit, too; they’d have richer, deeper relationships with more younger people who just might be more inclined to care for their caregivers as they age.

It would, of course, require a revolution in childrearing, Gheaus admits. And parents would have to get over the jealousy they often feel when their child loves someone else. But as parents struggle with work-life issues and the divide between the haves and have-nots grows, who is truly keeping our children’s best interests in mind? Alloparenting is the best way for both children and parents to flourish.